Nimrod: Hunting the Hunter

The mysterious post-Flood biblical figure Nimrod—the “mighty hunter before the Lord” (Genesis 10:9)—is an individual of infamy, regarded as the first empire-builder, original despot and the man responsible for leading the ill-fated construction of the tower of Babel. Naturally, the quest to identify the historical Nimrod has been a long one.

The fifth-century b.c.e. Greek historian Ctesias of Cnidus, working from the courts of Persia and purporting to have access to royal archives, recorded that a man named Ninus founded the Assyrian Empire and the city of Nineveh. Though much of Ctesias’s original work has been lost, it was preserved through secondary references. From his writings, we learn that Ninus was “by nature warlike and ambitious” and that he was married to a “glamorous prostitute” named “Semiramis, the most famous of all the women,” who had a “son named Ninyas.” Ctesias also described Semiramis’s role in the founding of Babylon.

Ctesias dated the reign of Ninus, mentioning a space of three centuries prior to the reign of Cyrus (r. circa 559–530 b.c.e.), preceded in turn by “more than 1,360 years” to Assyria’s founding by Ninus. Depending on the exact interpretation of these dates, various scholars have calculated Ctesias’s Ninus as having ruled sometime within the mid-late 23rd century b.c.e.—fitting rather well with the general Masoretic time frame for the biblical Nimrod. (For quotes and analysis, see Andrew Nichols’s The Complete Fragments of Ctesias of Cnidus: Translation and Commentary.)

The identification of Ctesias’s Ninus as Nimrod was made as early as the third century c.e. in the Clementine Recognitions. This equivocation continued to be popular on into the 19th century, when it was propounded most notably by the theologian Alexander Hislop in his book The Two Babylons. Yet during this same century, the historicity of both the biblical Nimrod and Ctesias’s Ninus began to be called into question.

An avalanche of archaeological discoveries from the power centers of Assyria and Babylon began emerging—most notable among them inscriptions, including detailed and newly deciphered king lists reaching back into deep antiquity. None bore the name “Ninus”—or “Nimrod,” for that matter. Without any scientific data to support the claim, Ctesias’s Ninus was rejected by scholars as a “wholly fictional” figure. (A little more nuance is given to his consort, Semiramis—see Sidebar 3, “Searching for Semiramis.”)

What, then, of Nimrod? He, too, is widely held to be a fictional figure, unmentioned in the earliest Mesopotamian records. That is, of course, unless he is to be identified by a different name within them. This is the premise on which the search for Nimrod has continued.

Possibilities

Various researchers and enthusiasts have proposed different options. These identifications are typically based either on name similarities or parallels to the brief biography for Nimrod found in the biblical account. Options include identifying the consonantal Hebrew name נמרד, NiMRoD, with the likes of Mesopotamian deities such as NiNuRTa (note that the m/n and d/t consonants are easily confused and interchangeable, cross-culturally), or the deity MaRDuk, whose first three consonants are the same as the last three of Nimrod’s.

An alternative approach is to select the ancient Mesopotamian ruler seen as best-befitting the cities attributed to Nimrod. These are listed in Genesis 10:9-10 (or verses 9-12, depending on whether one takes Asshur or Nimrod to be responsible for those mentioned in the latter verses; more modern translations tend to attribute these latter cities to Nimrod). Prof. Douglas Petrovich takes this approach in his recent book Nimrod the Empire Builder: Architect of Shock and Awe. Petrovich considers a number of proposed Nimrod figures and ultimately settles on Sargon of Akkad—otherwise known as Sargon the Great—as the best fit for ruler over the cities mentioned. This, however, is on the basis of Nimrod not founding any of them, nor having anything to do with the tower of Babel episode.

Yet if our search for Nimrod also takes into account the connection of the tower of Babel and confusion of languages episode recorded in Genesis 11 (per the following article in this issue), I believe a stronger candidate for this epic biblical figure emerges.

Enter Egyptologist David Rohl.

Rohl’s Nimrod

David Rohl is one of the more controversial figures in the world of biblical archaeology. He is most famous (or perhaps more accurately, infamous), for his radical “New Chronology” of ancient Egyptian history. Rohl’s model dramatically shrinks Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period, thus down-dating the pharaohs on through the famous New Kingdom Period by several centuries. These views have recently been heavily publicized, most notably in the popular Patterns of Evidence films.

Although I disagree with Rohl’s New Chronology model (see here and here), disagreeing with a researcher’s position in one area does not mean one cannot agree with his position in others. Unfortunately, we live in a tribalistic world of personality cults, in which there is little room for disagreement and nuanced positions—something seen most starkly in politics and media but that has also bled into academia.

Setting Egyptian chronology aside, when it comes to the topic of the early Genesis accounts in general, and the identification of Nimrod in particular, I believe Rohl makes an excellent case for one particular figure: The third-millennium b.c.e. Sumerian king Enmerkar.

Introducing Enmerkar

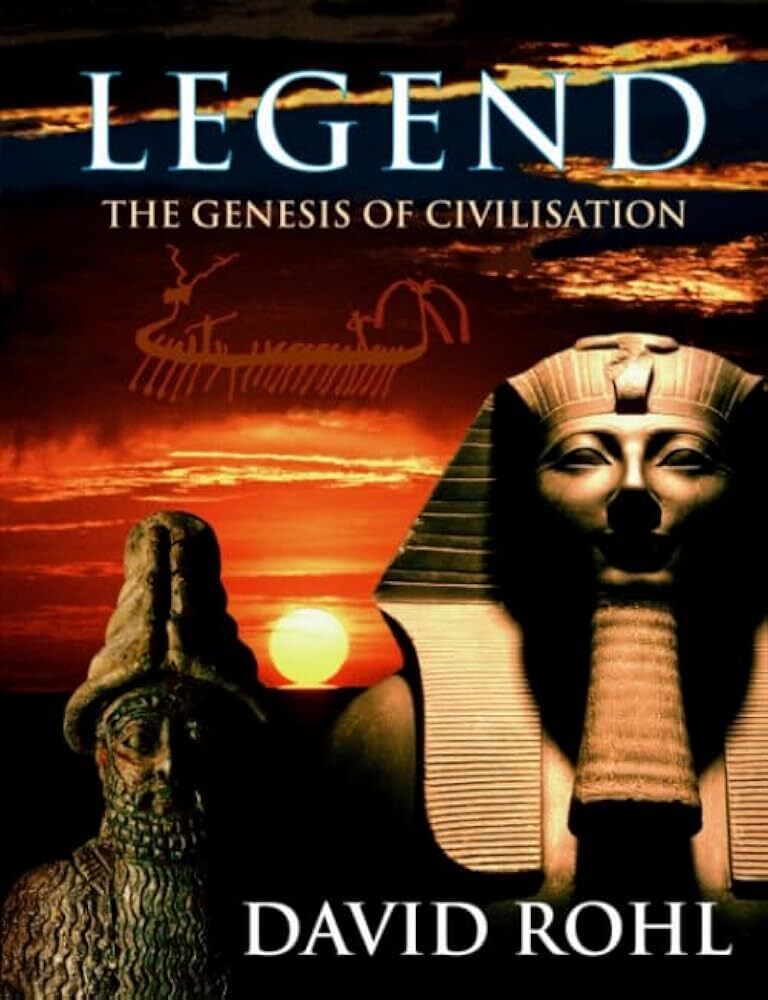

“When I first came across the Sumerian epics of Enmerkar and Lugalbanda, I was immediately struck,” Rohl writes in Legends: The Genesis of Civilisation, noting the parallels between the Sumerian, Assyrian and biblical texts. “Enmerkar … turn[s] out to be a major player in our story and a famous, but historically lost, biblical character.”

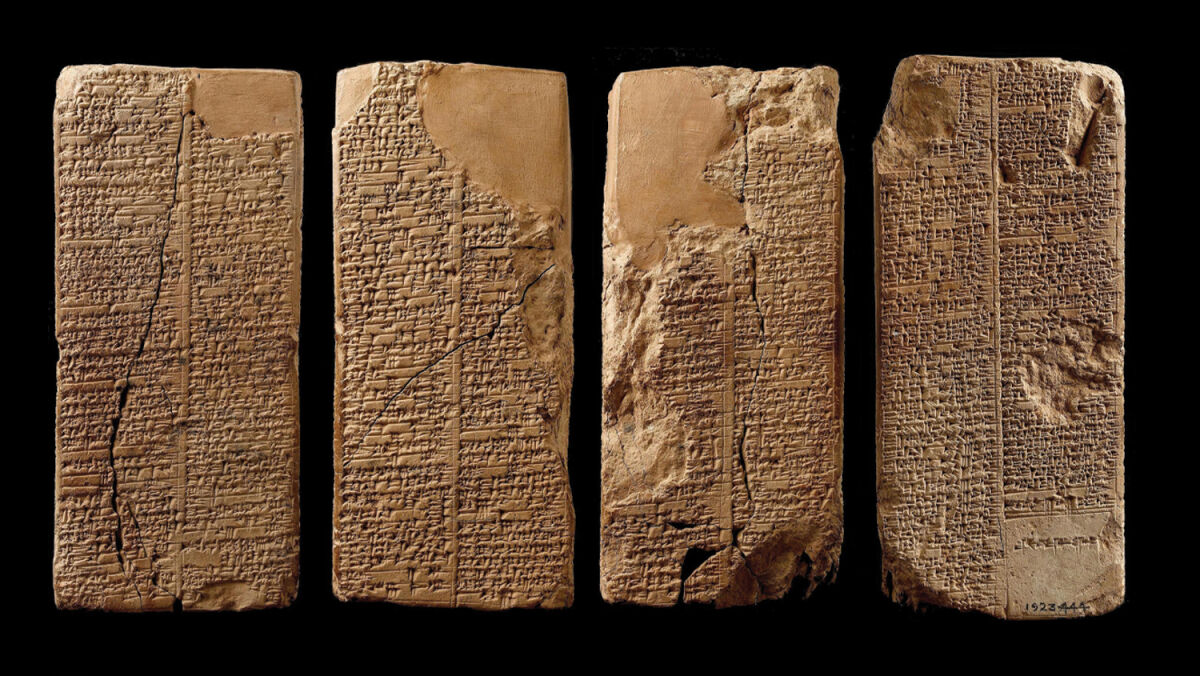

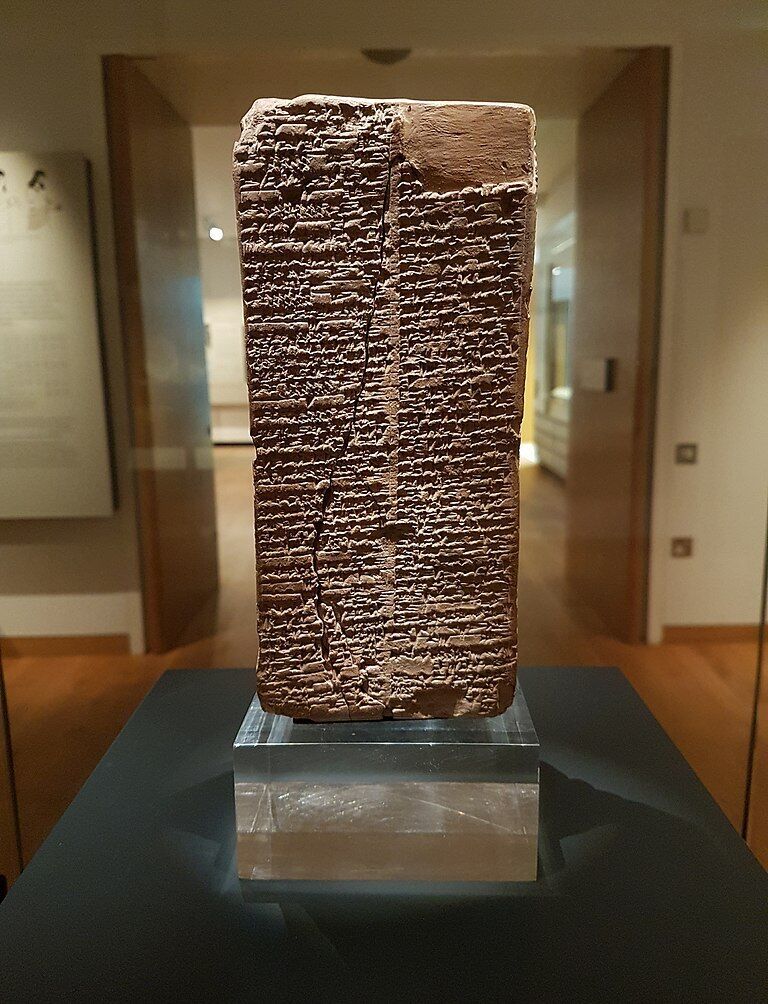

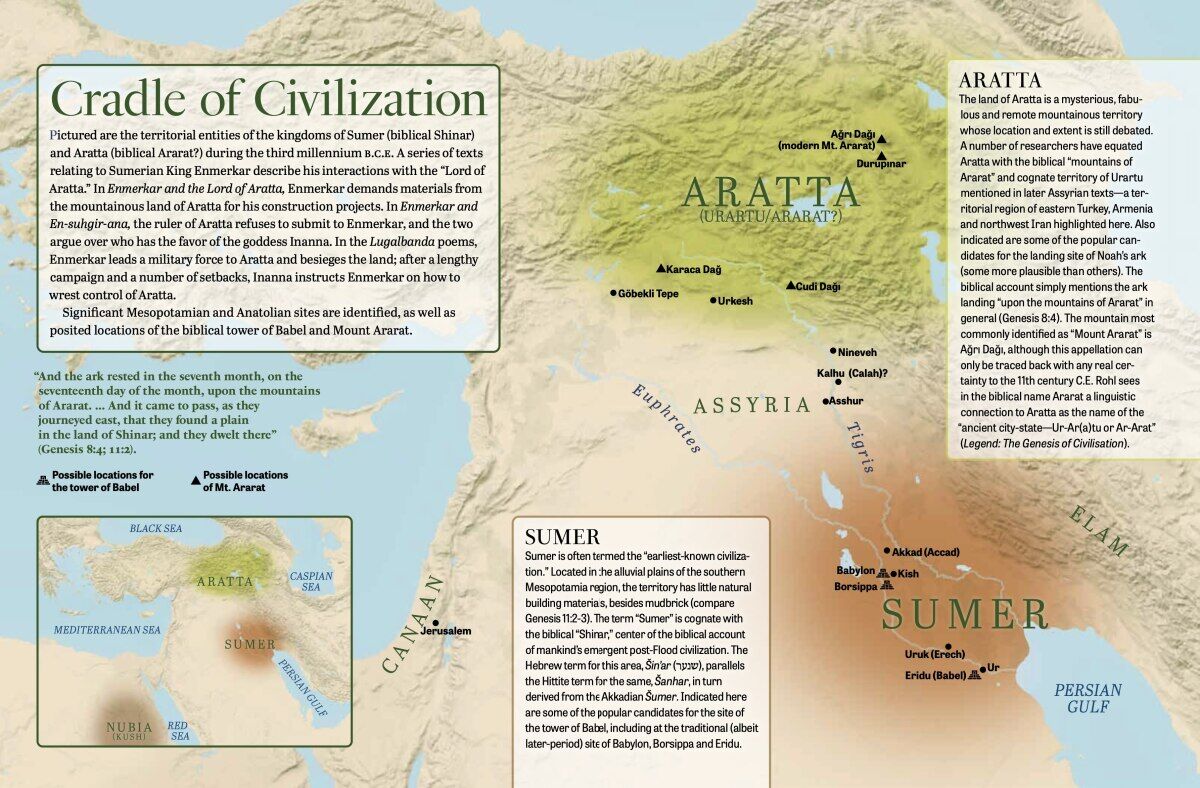

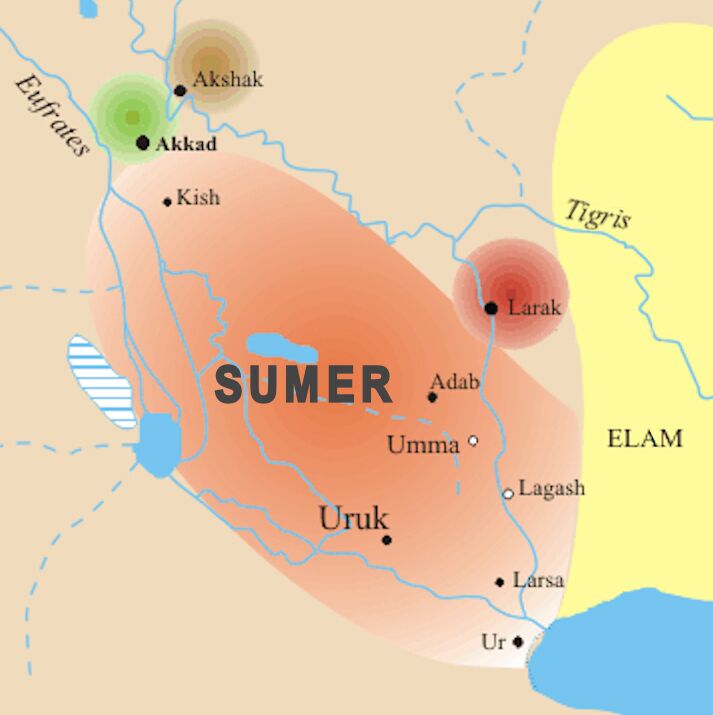

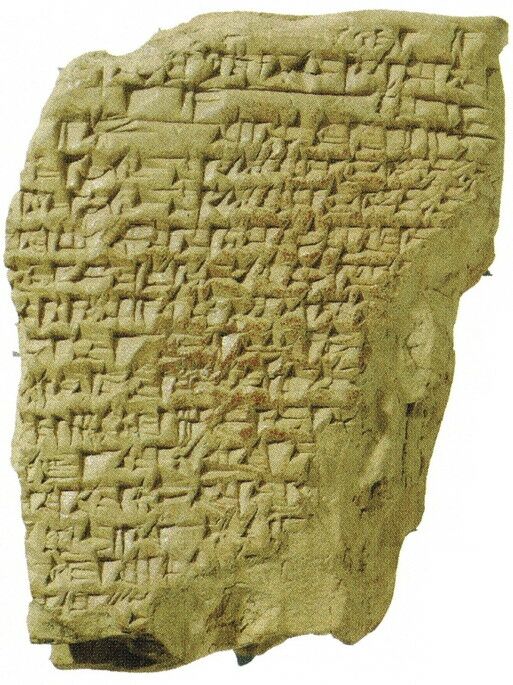

One of the best-known artifacts mentioning Enmerkar is Weld-Blundell 444, better known as the Sumerian King List (or rather, a copy of it). This clay prism was found in 1922 during an excavation at the ancient city of Larsa (in modern-day Iraq). Dating to circa 1800 b.c.e., the artifact—housed in Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum—lists the ancient rulers of Sumer and surrounding regions. This “Sumer” is a form of the biblical name Shinar—the name of the great southern Mesopotamian plain where post-Flood mankind descended to (and where Nimrod began his rule—Genesis 10:10; 11:2).

The Sumerian King List begins by describing a list of rulers of vast ages, until “the flood swept over.” Further down in the list, after the time of the Flood—when lifespans began to rapidly decline from the 900-year range (paralleling the pre-Flood ages of biblical figures)—a certain Sumerian king emerges by the name of Enmerkar. He is recorded on the list as having reigned about 420 years. While the Bible does not give Nimrod’s lifespan, those of his generational contemporaries—Eber’s 464 years, Shelah’s 433 (Genesis 11:14-17)—point to this same range.

The name Enmerkar is also a tantalizing fit. Rohl writes:

[S]cholars tend to write the Sumerian hero’s name as “Enmerkar.” However, one copy of the Sumerian King List, found at Nippur and published by Arno Poebel in 1914, gives En-me-er-ru-kar. We might, therefore, justifiably vocalize the name as Enmerukar. … The four syllables En-me-ru-kar can be understood as a name plus an epithet—once it is realized that kar is the Sumerian word for “hunter” (Akk. Habilu). Thus we have King “En-me-ru, the hunter” (ibid).

This compliments the biblical text, which identifies Nimrod as “the hunter.” Note too, the name Enmer carries within it the first three key consonants found in the name Nimrod, N-M-R. It therefore stands to reason that this may have constituted the original name—with the Hebrew Nimrod, meaning “we will rebel,” likely being a play on the core name to reflect this negative meaning. (Other biblical examples of this sort of symbolic name-tweaking include Chushan-Rishathaim, Jerubbesheth, Ishbosheth and Mephibosheth—see here and here for more detail.)

Heredity and Environment

In genealogy, biblical Nimrod is listed as the son of Cush, meaning “black.” (Interestingly, the Sumerians referred to themselves as the “black-headed ones.”) Rohl equivocates Cush with Enmerkar’s listed father: Meskiag-kash-er. (For an interesting tidbit connecting this individual with the biblical Cush, see Sidebar 4, “Cushite Conundrum.”) Meskiagkasher is in turn listed as the son of a solar deity called Utu, also known as Shamash and Amna. Perhaps this corresponds with Cush’s father, Ham (meaning “hot”)?

“Nimrod, as the grandson of Ham, belongs to the second ‘generation’ after the Flood (Noah—Ham—Flood—Cush—Nimrod),” continues Rohl. “[T]his is also true of Enmerkar who is recorded in the Sumerian King List as the second ruler … after the Flood (Ubartutu—(Utnapishtim)—Flood—Meskiagkasher—Enmerkar)” (ibid).

In its basic form, the Sumerian King List is a list of names; it provides only brief detail about a select few kings. Enmerkar is one of the few names to have added information. He is recorded to have founded the city of Uruk (“who built Uruk”). This alone is notable, as Uruk has long been identified as the biblical city Erech, the second city attributed to Nimrod: “And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech …” (Genesis 10:10). But Uruk was not the only place ruled by Enmerkar. He also ruled the region of Sumer, further fitting with the biblical Nimrod as king of territory throughout the “land of Shinar” (Sumer).

Not a lot is known about the historical reign of Enmerkar. Proposed chronologies for the very early rulers on the Sumerian King List vary significantly. “[G]iven the paucity of documents recording kings’ names found in an archaeological context, it has proved difficult to pinpoint exactly when specific rulers reigned in relationship to the archaeological stratigraphy or pottery periods,” Rohl writes. “Many of the famous rulers of Sumer—heroes such as Enmerkar … have not been fixed with any real confidence into the early archaeological eras” (ibid). Enmerkar’s rule is typically placed somewhere within the early to middle part of the third millennium b.c.e.

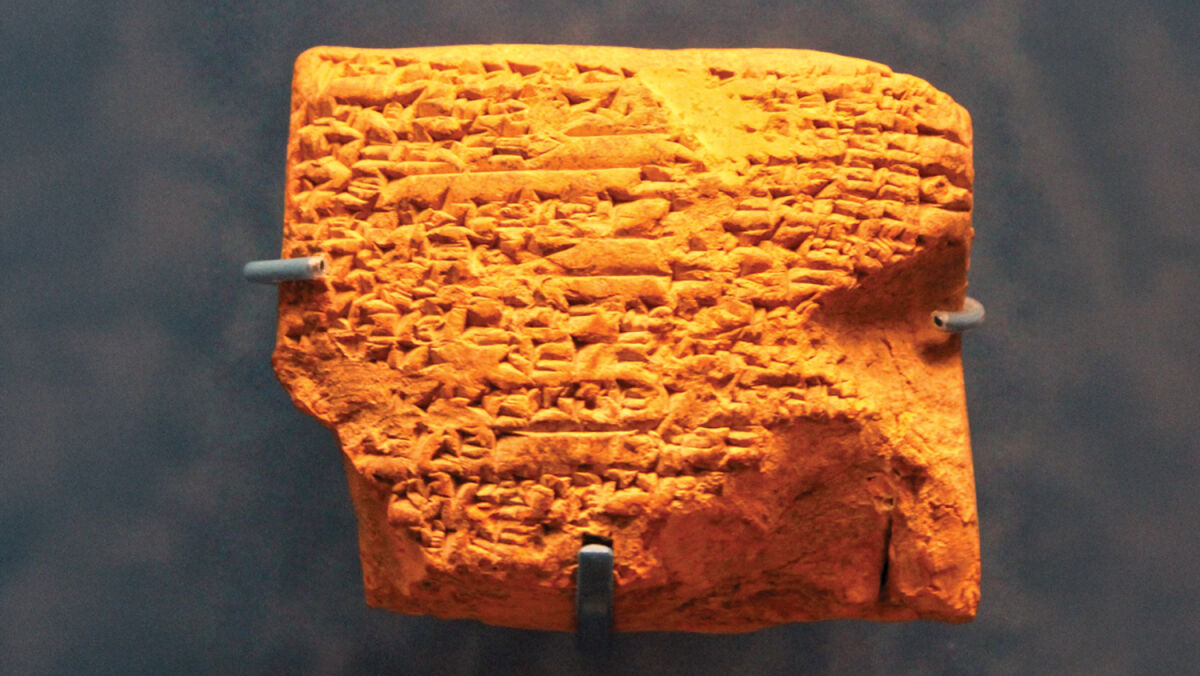

Setting the Sumerian King List aside, there is, at least compared to other Sumerian figures, a treasure trove of narrative information available about Enmerkar. There exists an ensemble of inscriptions in relation to this monarch mentioning tower-building enterprises—and not only that, these enterprises are mentioned in the context of a confusion of languages. A state of confusion, however, not in relation to Enmerkar’s city of Uruk but another city entirely.

The Matter of Aratta

These Sumerian inscriptions date to around 2100 b.c.e. and collectively comprise an original story known as Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. The record describes dialogue between Enmerkar and a ruler of Aratta, a mysterious and distant mountainous land, equated by some scholars with the Urartu of Assyrian texts and biblical Ararat, generally located in the region of modern-day Turkey, Armenia and northwest Iran. (This is another detail that fits nicely with the biblical account, which identifies Ararat as a key location in the post-Flood world.) Another interesting fact is that Enmerkar refers to himself in the text as one “reared on the soil of Aratta,” nicely paralleling the portrayal of Nimrod leading an entourage down from the Ararat region to the plains of Shinar/Sumer (Genesis 11:2).

In the Sumerian text, Enmerkar threatens the ruler of Aratta, warning him that if he does not support the construction of a tower for “the great queen of heaven,” he will wreak havoc on Aratta “like the devastation which swept destructively” (a nod to the Flood?).

Partway into the long text, there is an astonishing paragraph addressing a state of linguistic confusion, as well as territories biblically associated with Nimrod:

Chant … the incantation of Nudimmud: “… may the lands of Cubur and Hamazi, the many-tongued, and Sumer [Shinar], the great mountain of the me of magnificence, and Akkad [biblical Accad—the third city attributed to Nimrod], the land possessing all that is befitting, and the Martu [Amorite] land, resting in security—the whole universe, the well-guarded people—may they all address Enlil together in a single language! … Enki, the lord of abundance and of steadfast decisions, the wise and knowing lord of the land, the expert of the gods, chosen for wisdom, the lord of Eridu, shall change the speech in their mouths, as many as he had placed there, and so the speech of mankind is truly one” (emphasis added throughout).

Rohl and certain other researchers (including the aforementioned Dr. Petrovich) identify this city of Eridu—whose god Enmerkar pleads with to restore the unity of language—as the original Babel. In Hebrew, the terms Babel and Babylon are used interchangeably. Yet the more well-known “Babylon”—capital of Nebuchadnezzar’s empire—is archaeologically a comparatively late city, certainly compared to the others mentioned in the Genesis 10 account. This has led many to question its nature as described in these earliest biblical references.

Eridu, on the other hand, is a city from deep antiquity. Traditional dating of this site—Tell Abu Shahrain—puts the first establishment of Eridu somewhere around the fifth millennium b.c.e. (with potential links even to the family of Cain). The extreme antiquity of the site is evident from its sorely degraded ruins; its construction on untouched, virgin sands; and Eridu’s place as the “first city” on the Sumerian King List. But its connection with Babylon is even more direct: Eridu bears the very same cuneiform logogram name as that of the later Babylon, nun.ki., thus leading to the conclusion that this was the original city of Babel and that the name simply shifted to the later, more well-known site of Babylon.

Confusion at Eridu

In Readings From the Ancient Near East, scholars Dr. Bill Arnold and Dr. Bryan E. Beyer provide an interesting alternate translation of the passage from Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta: “Once … the whole universe, the people in unison, spoke to Enlil in one tongue. … Then Enki … lord of Eridu, changed the speech in their mouths, brought contention into it, into the speech of man that had been one.”

This variant reading is even more striking, especially in relation to the biblical account. Whatever the most precise translation is, the text’s association with the biblical account of confusion of languages is unmistakable.

This connection was first confirmed by Assyriologist Dr. Samuel Noah Kramer in his 1968 Journal of the American Oriental Society article “The ‘Babel’ of Tongues: A Sumerian Version.” The Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta text had already been partly translated and tentatively associated with the biblical confusion of languages, but the discovery of an additional fragment made the meaning of this particular section clear. “Our new piece, therefore, puts it beyond all doubt that the Sumerians believed that there was a time when all mankind spoke one and the same language, and that it was Enki, the Sumerian god of wisdom, who confounded their speech,” wrote Kramer.

Reaching Unto Heaven

There is another Sumerian text associated with Enmerkar, titled Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana. This inscription is considered a sequel, of sorts, to Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta.

Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana begins by mentioning one of Enmerkar’s towns as a “city which reaches from heaven to earth.” This is almost verbatim the language of Genesis 11:4, which describes Babel as a “city, and a tower, with its top in heaven.”

The Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana text goes on to describe some chest-thumping antics between Enmerkar and the ruler of Aratta, En-suhgir-ana, with each one threatening to subjugate the other. Enmerkar brags that the great goddess Inanna, “queen of heaven” (a goddess later known variously by the famous names Ishtar, Astarte, Ashtoreth and Isis), is on his side. Apparently, Enmerkar had “brought the goddess of Aratta down to the Mesopotamian plain and erected for her a magnificent sacred precinct called the Eanna or ‘House of Heaven,’” notes Rohl (op cit).

Enmerkar proceeds to boast about his sexual escapades with her (“even though she is not a duckling, she shrieks like one”). The text goes on to feature sorcery and trickery. Ultimately, the ruler of Aratta submits to Enmerkar before the text tails off, becoming too fragmentary to read.

Back to the Classical Authors

In the introduction, we highlighted the Ninus figure described by the fifth-century b.c.e. Ctesias—the “first king” of note, the first to attempt an empire. But Ctesias was not the only classical period author to mention such a notable “original king.” A similar individual is described by the third-century b.c.e. Babylonian historian Berossus.

In his work Babylonaica, Berossus wrote: “After the Flood, Euechsios ruled over the land of the Chaldeans four neroi. And after him his son Chomasbelos took over the kingship ….”

Berossus’s first post-Flood king, Euechsios, has long been equivocated by researchers with the Enmerkar of ancient Sumerian literature. Stanley Mayer Burstein’s The Babylonaica of Berossus contains the following comment on this passage:

Euechsius = Enmerkar (Jacobsen, King List, 86 n. 115). Jacobsen suggests that the reading Euechsios is corrupt and that Berossus actually wrote Euechoros (cf. Jacoby, FGrH, 3Cl, p. 384 note ad line 4). … Apropos of this William W. Hallo (“Beginning and End of the Sumerian King List in the Nippur Recension,” jcs, 17 1963, page 52) noted that Berossus was strongly interested in the apkallu tradition and that Enmerkar is the first post-Flood king associated with an apkallu (cf. van Dijk, 45, line 8; Reiner, 4 lines 10-13).

This “apkallu tradition” is specifically the association of a demigod “sage” with a particular ruler. An example of this is found in the “Uruk List of Kings and Sages,” a copy of a text dating to 165 b.c.e., found in the Seleucid temple of Anu at Bit Res. Similarly to Berossus’s Babylonaica, it reads, in part: “After the flood, during the reign of Enmerkar, the king, Nungalpirigal was sage, whom Ishtar brought down from heaven to Eana.”

Andrew Nichols, in The Complete Fragments of Ctesias of Cnidus: Translation and Commentary, further highlights the connection between the sources utilized by Berossus and Ctesias. “[Robert] Drews … like [Georges] Goossens, asserts that Ctesias’s Assyrian chronology almost certainly comes from Babylonian records and may reflect the same tradition as Berossus’s date for the beginning of Babylonian history.”

Gathering Thoughts

Speculation about the exact identity of rulers mentioned by much later classical authors aside, the parallels between the ancient ruler Enmerkar of Sumerian lore and the biblical Nimrod are striking.

“Look at what we have here,” concludes Rohl, summarizing the evidence at hand:

Nimrod was closely associated with Erech—the biblical name for Uruk—where Enmerkar ruled. Enmerkar built a great sacred precinct at Uruk and constructed a temple at Eridu [Babel]—that much we know from the epic poem Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. The Sumerian King List adds that Enmerkar was “the one who built Uruk.” Nimrod was also a great builder, constructing the cities of Uruk, Akkad and Babel. Both Nimrod and Enmerkar were renowned for their huntsmanship. … Both ruled over their empires in the land of Shinar/Sumer. … We have now learnt so much about Enmerkar that he has naturally become our prime suspect (ibid).

In sum: It is true that other Nimrod candidates have certain interesting individual links either in name or in deed with the figure recorded in Genesis. And it is certainly possible that these candidates and deities could perpetuate attributes originating from a common core individual.

But as far as accounts relating to a singular, early individual go, Enmerkar and his related texts have Genesis 10 and 11 written all over them. As such, I would agree with the words of Rohl, that we have in Enmerkar a figure who is “none other than the first great potentate on Earth—the biblical Nimrod.”

Sidebar 1: The ‘Sumerian Problem’

History books identify Sumer (biblical Shinar) as the “cradle of civilization,” with the Sumerians often called the “first civilization.” Alongside the Sumerian city-states, another civilization, centered at Akkad, emerged—eventually overtaking Sumer as the dominant entity in the region. While these groups existed together, the Akkadians and the Sumerians shared close relations and similarities, even to the point of being described as “symbiotic.” “It is impossible to tell the story of one without the other,” notes Paul Cooper in his documentary series Fall of Civilizations.

There was a problem, however: Even though they practically lived together, Akkadians and the Sumerians both spoke entirely different, completely unrelated languages! The same is true of the neighboring Elamites. Both the Sumerian and Elamite languages are known as “language isolates” (languages with no known links or roots to any other ancient language). How did such a linguistic babble emerge from the same general area?

This conundrum is known as the “Sumerian Problem.” There are many theories for its cause. One is that the Sumerian people migrated into the region from the East, via the Indus Valley—a migration perhaps driven by a rise in water levels in the Persian Gulf, leading to traditions of a great flood. Yet there are problems with this interpretation. There is no evidence for such a journey and no linguistic links with the East. It doesn’t explain how the Akkadians and Sumerians are so closely tied, with the Akkadians likewise preserving flood traditions. And the Sumerian civilization was the first to be established in Mesopotamia—Akkad emerged later. Why, then, is Sumerian the isolate?

Modern theories aside, the ancients had their own explanation: Such linguistic confusion was caused by a deity at Eridu, as told in the late third millennium b.c.e. Sumerian epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (as described above). Another is told in a later, early first millennium (eighth or seventh century) b.c.e. Assyrian document, likewise describing an event in ancient Babylon. The damaged inscription reads:

… he the father of all the gods had repudiated; the thought of his heart was evil. … of Babylon he hastens to the submission, small and great he confounded on the mound. Their walls all the day he founded; for their destruction in the night … he did not leave a remainder. In his anger also his secret counsel he pours out; to confound [their] speeches he set his face. He gave the command, he made strange their counsel (translation by Assyriologist George Smith, The Chaldean Account of Genesis).

The word “confound” here is the Assyrian-Semitic word balel—and precisely the same word is used in the biblical account of the building of a tower, and a subsequent confusion of languages. “Therefore was the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did there confound [‘balal’] the language of all the earth …” (Genesis 11:9). The language of this Assyrian inscription dramatically parallels the biblical account.

For more on this subject, see “The ‘Sumerian Problem’—Evidence of the Confusion of Languages?”

Sidebar 2: What Was the Tower of Babel?

For most, the tower of Babel probably conjures up images of a tall, narrow tower spiraling up into the heavens. This classic depiction is found in numerous famous works of art. Yet it is rather anachronistic—most likely influenced by early Islamic minarets (towers for calling to prayer), such as the Samarra minaret in Iraq (right).

In reality, the tower of Babel would have been a ziggurat, a known temple-tower phenomenon from ancient Mesopotamia. These mountain-like, brick-built stepped structures (compare Genesis 11:3)—perhaps the most famous and well-preserved example being the Ziggurat of Ur (below)—bore up to seven successive levels of sanctity, culminating in a temple structure located at the summit—the residence of the city’s patron deity. In identifying Eridu with Babel, David Rohl believes that the remains of the massive early ziggurat there are none other than the remains of the biblical tower.

This somewhat different tower concept to that commonly portrayed in art actually fits well with the account of Josephus about the tower of Babel—that though this tower was certainly tall, “the thickness of it was so great, and it was so strongly built, that thereby its great height seemed, upon the view, to be less than it really was. It was built of burnt brick …” (Antiquities of the Jews, 1.4.3). A tower wider and more mountain-like, rather than tall and slender—fitting well the description of a ziggurat.

Sidebar 3: Searching for Semiramis

While Ctesias’s Ninus is widely regarded as ahistorical, some nuance is given to his wife, Semiramis—although not much. She is widely regarded to have been based on the much later, late ninth-century b.c.e. Queen Shammuramat (the Akkadian equivalent of the Greek name Semiramis), wife of Assyrian King Shamshi-Adad v—an equivocation based largely on name-similarity.

This figure is, of course, nearly 1,500 years later than the period ascribed by Ctesias to Semiramis. And her husband is certainly no parallel to Ctesias’s Ninus in name or deed.

Yet do not be too quick to pass off Semiramis as simply referring to this later-period queen of the same name: There is reason to suspect this name was already well established and renowned from earlier periods. And the evidence for this comes from the Bible itself.

An early equivalent name is found in the Hebrew Bible. 1 Chronicles 15:18, 20, and 16:5 mention a certain “Shemiramoth” (paralleling the Akkadian Shammuramat and rendered in the Greek Septuagint as Semiramoth). This individual is described as being on the scene during the early part of King David’s reign (circa 1000 b.c.e.)—predating Shamshi-Adad v’s Shammuramat by two centuries. Another figure of the same name is mentioned during the early ninth-century b.c.e. reign of King Jehoshaphat (2 Chronicles 17:8)—likewise predating Queen Shammuramat. Of this biblical name Shemiramoth, Ellicott’s Commentary notes, “This peculiar name resembles the Assyrian Sammurramat, the classical Semiramis.” The existence of such a name prior to the later queen for not only one, but two biblical figures, logically implies an already-established use in antiquity, perhaps deriving from some earlier figure of renown.

Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon offers the biblical name as meaning “‘most high heaven,’ Semiramis,” based on the first part of the name שמירמות reflecting a contraction of the plural word “heavens” (שמים), and the last part, רמות, meaning “heights.” If so, this could befit the divine appellation for the Mesopotamian goddess, “queen of heaven”—known to the Sumerians as Inanna, the Assyrians and Babylonians as Ishtar, and the Levantines as Astarte and Ashtoreth.

Many traditions have developed around Nimrod having a wife of renown, with the attributes of Semiramis. In identifying Enmerkar as Nimrod, are there any indications he had such a partner? There is one particular, intriguing possibility.

The fifth-century b.c.e. Greek historian Herodotus attributes to Semiramis the creation of artificial riverbanks and water systems. “Semiramis: It was she who built dykes on the plain, a notable work; before that the whole plain was wont to be flooded by the river” (Histories, 1.184). The first-century b.c.e. Diodorus Siculus wrote at length about Semiramis’s canals, ditches and river works, particularly in relation to the founding of Babylon and a reworking of the Euphrates watercourse. Other early historical accounts do the same.

Interestingly, an ancient Sumerian inscription known as AD-GI4, or “Archaic Word List C,” mentions a consort of Enmerkar, bearing a derivative form of his name, “Enmerkar-zi,” constructing waterworks of various sorts. “Enmerkar and (his) wife Enmerkar-zi, who know (how to build) towns (made) brick and brick pavements. When the yearly flood reached its proper level, (they made) irrigation canals and all kinds of irrigation ditches” (translation from “Remarks on AD-GI4,” Miguel Civil).

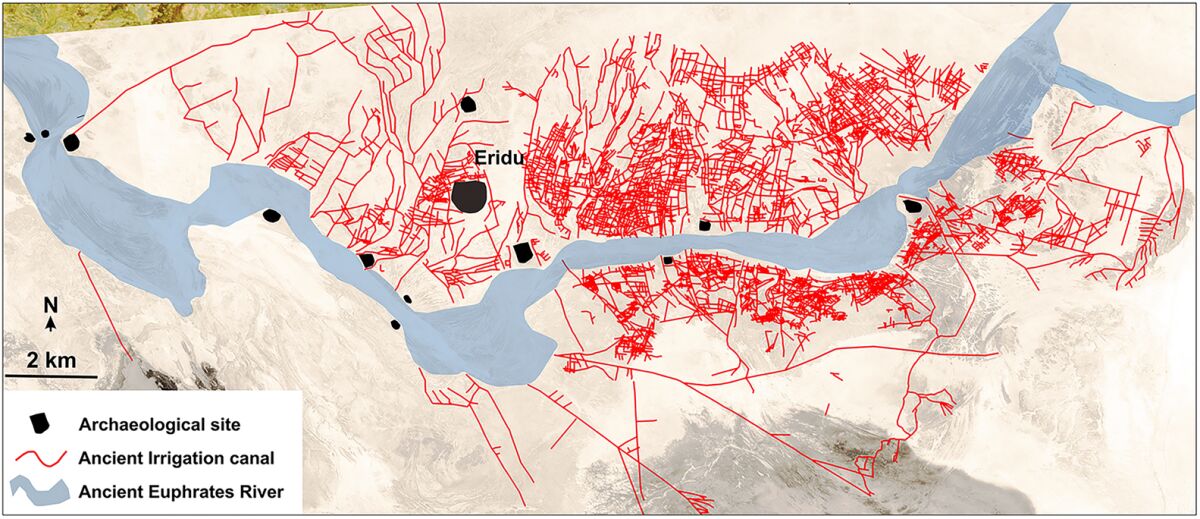

Additionally, earlier this year, new research was published in the journal Antiquity mapping at Eridu a “vast and well-developed network of artificial irrigation canals, including more than 200 primary and large canals … between 1 and 9 kilometers long, and between 2 and 5 meters wide,” with “more than 4,000 minor and branch canals connected to the main canals.” This canal network is being hailed as demonstrating a level of sophistication in hydraulic engineering and agricultural planning. The researchers hope to “conduct additional research on the chronology of the canals … comparing the character and dimensions of the canals and farms with contemporaneous descriptions in the texts of the cuneiform tablets” relating to these waterworks (“Identifying the Preserved Network of Irrigation Canals in the Eridu Region, Southern Mesopotamia”).

Sidebar 4: Cushite Conundrum

One particularly confusing point for scholars about Nimrod’s heredity and accomplishments is that while the territory described in Genesis 10:10-12 is clearly that of Mesopotamia, Nimrod is a son of Cush—the progenitor of the tribes of sub-Saharan Africa. This term (Cushite/Kushite) is used ubiquitously throughout the Bible for such individuals.

“One puzzling detail in the Nimrod story is his genealogy,” says Dr. Andrew Henry, host of the popular YouTube channel Religion for Breakfast. “He’s listed as the son of Cush.

But Cush is the Hebrew name for ancient Nubia, an African kingdom south of Egypt. In the biblical Table of Nations, Cush is a descendant of Ham, while Mesopotamian nations are usually traced through Shem. So Nimrod’s placement here is odd. It’s also geographically confusing, since Nubia and Mesopotamia are nowhere near each other” (“Nimrod: The Bible’s Most Mysterious King”).

Henry offers an alternate solution from Dr. Yigal Levin, that the name may instead be confused with the Mesopotamian site of Kish.

Rohl offers a different solution in light of identifying Enmerkar as Nimrod, and his father Meskiag-kash-er as Cush (the shorter Hebrew/Semitic name representing a hypocoristicon of the longer—similar to the biblical “Pul” used for Tiglath-Pileser iii). Of Meskiagkasher, the Sumerian King List adds a single line of detail alongside his name: He “entered the sea and disappeared” (emphasis added).

“If Meskiagkasher can be identified with the biblical Cush then we are entering new territory in both the literal and metaphorical senses,” Rohl writes.

The Bible tells us that the sons of Noah were the progenitors of all the great nations of the ancient Near East. I am referring here to the famous so-called “Table of Nations” which takes up the whole of chapter 10 of Genesis. …

Josephus, having retold the story of Nimrod’s tower of Babel and the subsequent confusion of tongues, goes on to explain that Cush, his three brothers and their followers journeyed to their new homes across the sea. … [T]he traditions of Sumer and the Bible may hold, between them, a vague memory of a great seafaring adventure which brought Meskiagkasher/Cush and his family to Africa” (Legend: The Genesis of Civilisation).