Famous Ancient Battles NOT Mentioned in the Bible—Or Are They?

The Bible is full of detailed descriptions of battles and upheaval. Many of these have been corroborated by archaeology, such as the siege of Jerusalem, the siege of Lachish, the battle of Jericho, the siege of Samaria and the siege of Gath.

There are, however, some extremely significant battles not specifically mentioned that occurred in the surrounding geographical region during the time period described in the Bible. Is this perhaps supporting evidence for the long-held theory that the Bible was written long after the fact—that it is, at best, a loose collection of vague, gap-filled historical memories, or at worst, a work of outright fiction?

But this is hardly the case. The Hebrew Bible’s account is clearly a very selective text largely focused on events relating directly and specifically to ancient Israel. That being said, there is evidence in the biblical text of various famous geopolitical upheavals that occurred throughout the late second and first millenniums b.c.e. If not mentioned directly, they are certainly hinted at. Here’s a selection of such events.

Battle of Kadesh

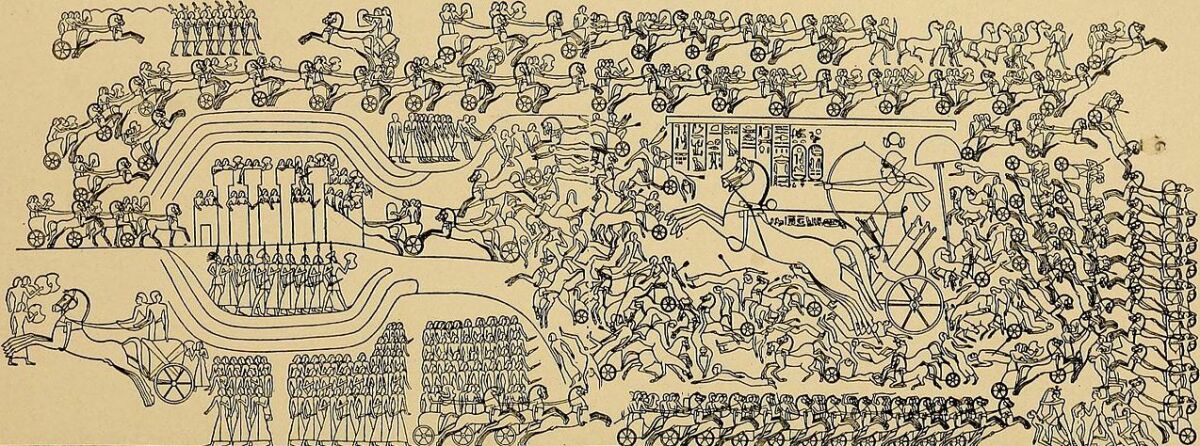

“No battle fought in antiquity is so well-documented as the clash between the Egyptians and the Hittites before the city of Kadesh on the Orontes in 1274 b.c.,” states Egyptologist Prof. Boyo Ockinga.

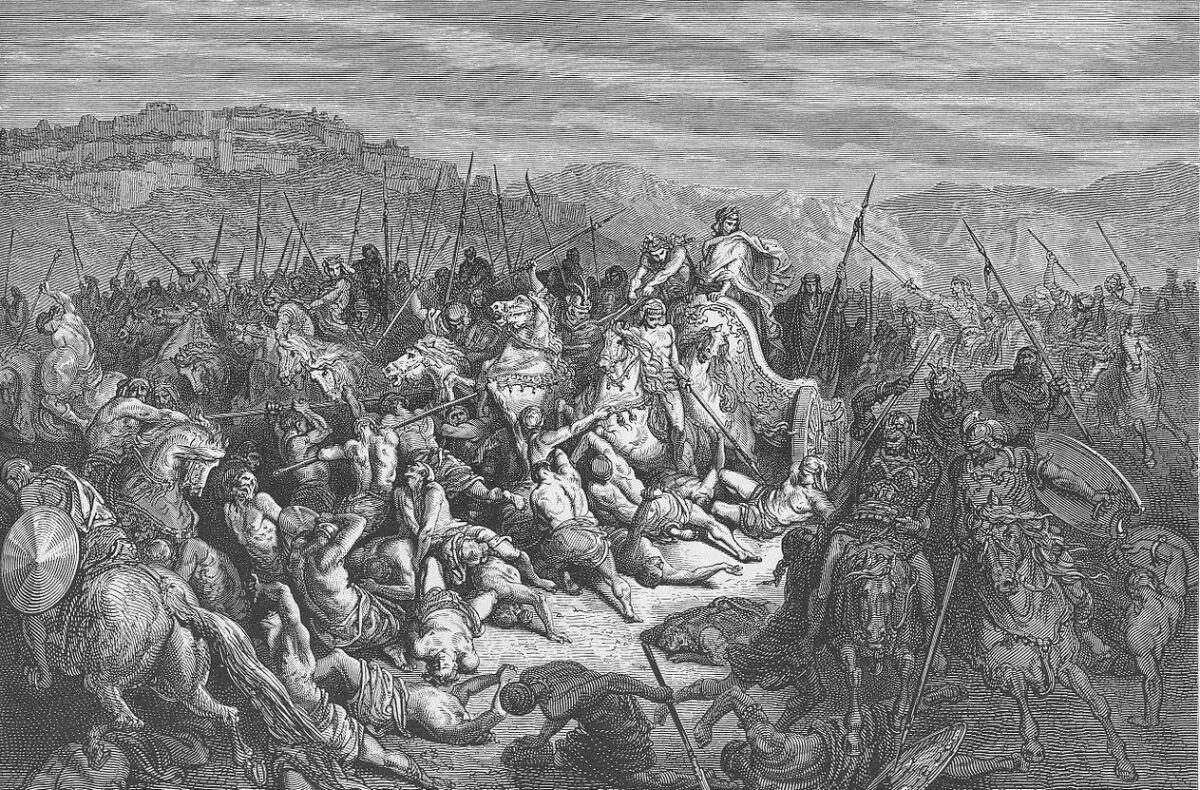

By all accounts, the Battle of Kadesh, along the border of Lebanon and Syria, was a record-breaking conflict. It is commonly cited as history’s largest chariot battle, featuring somewhere between 5,000 and 13,000 of the wheeled menaces, with up to as many as 70,000 combatants. It is also the earliest-known battle to feature documented military formations and strategies.

And there is no hint about it in the Bible. Or is there?

The dating of this battle in accordance with internal biblical chronology places it somewhere in the first half of the biblical “judges” period. And it is during this time that we find a rather remarkable and unique account relating specifically to the north of Israel (the region of the nation closest to the location of the Battle of Kadesh): We find description of a massive flush of chariots.

“And the Lord gave them [the Israelites] over into the hand of Jabin king of Canaan, that reigned in Hazor; the captain of whose host was Sisera, who dwelt in Harosheth-goiim. And the children of Israel cried unto the Lord; for he had nine hundred chariots of iron; and twenty years he mightily oppressed the children of Israel” (Judges 4:2-3).

Sisera’s force of “nine hundred chariots of iron” is the only significant biblical mention of chariots during the roughly 350-year period of the judges. And this kind of incredible strength is ordinarily laughable—until the parallel historical context of the Battle of Kadesh is considered.

The outcome of the Battle of Kadesh, fought for control over the wider Levantine strip, is actually still debated, since most of our understanding of it comes from biased Egyptian sources. The battle did end with a peace treaty, but both sides claimed victory. Whatever the case, this chariot battle clearly accounts for the never-before-seen influx of chariots into and around the Holy Land. And this helps to explain the biblical account of Sisera’s force (on the scene probably several decades after the Battle of Kadesh): a military leader commanding a massive force of 900 chariots.

There is plenty of debate about the identity of Sisera. One suggested meaning for the name “Sisera” is the Egyptian title “Ses-ra,” meaning “servant of Ra.” Ra was one of the four Egyptian chariot divisions used at Kadesh; considering this, perhaps Sisera was a mercenary captain originally associated with this division in the Battle of Kadesh.

The biblical description of “iron chariots” favors the heavy Hittite chariots (as opposed to the light and nimble Egyptian vehicles). Perhaps this leader came into possession of the many Hittite chariots that were reportedly abandoned in the field during the Battle of Kadesh.

With many of the particular details, we can only speculate. Still, the wider picture the biblical text provides, of a gigantic chariot army situated in the north in the 13th century b.c.e., fits perfectly with this very specific historical event. (For more information about the biblical account of Sisera and Jabin’s oppression of Israel, read the following article here.)

Battle of the Delta

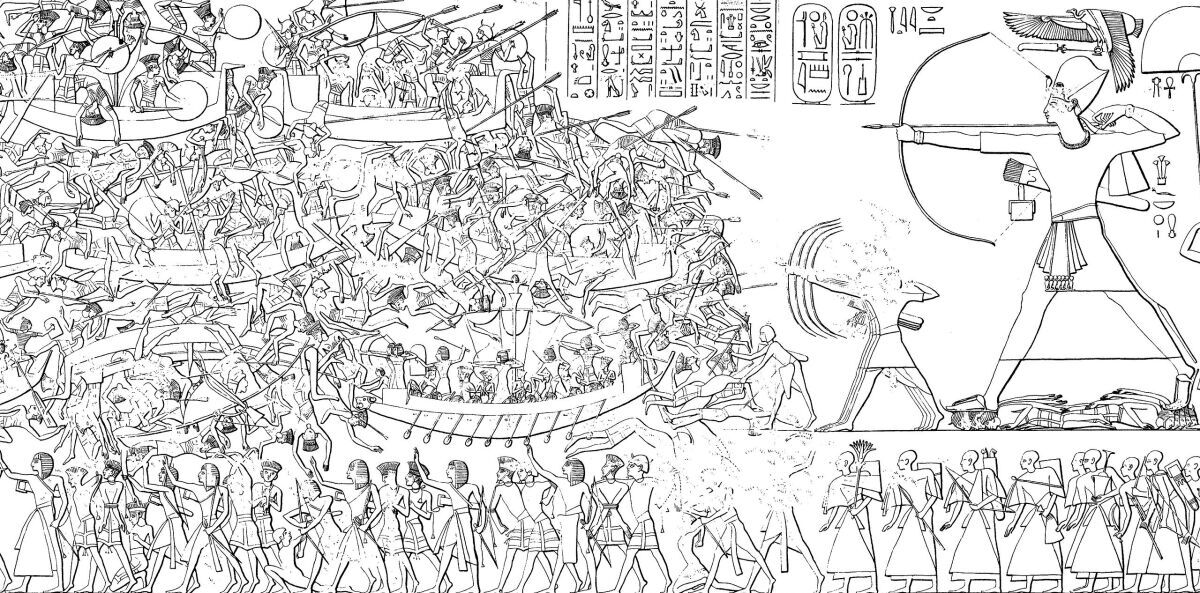

The Battle of the Delta (circa 1175 b.c.e.), as well as other related battles around the start of the 12th century b.c.e., constituted a broad invasion by a peculiar group from the Mediterranean islands known as the “Sea Peoples.” The Sea Peoples included a fierce group known as the “Peleset,” a word directly related to the Hebrew root for “Philistine.”

At the time of this confrontation, Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses iii had just defeated the Sea Peoples in a land battle in Syria. He rushed back to Egypt’s Nile Delta to prepare for an inevitable naval invasion. Luring the massive enemy fleet into the mouth of the Nile, Ramesses then trapped them in an ambush that ultimately resulted in an Egyptian victory.

What is particularly strange about the invasion of the Sea Peoples is that they took their women and children with them, leading researchers to believe that they were migrants looking for a new place to settle. The typical interpretation of events is that soon after being defeated by Ramesses iii, these people began settling in the southern Levant, becoming the “Philistines” of biblical lore. Indeed, genetic research of burials in “Philistine” sites has shown that the original inhabitants were Canaanites, who were eventually supplanted by a Mediterranean influx from the 13th–12th centuries b.c.e. onward, namely from the island of Crete (biblical Caphtor).

Again, this specific battle is not directly referenced in the biblical account. But beginning in this very time period (around the middle part of the judges period onward), we begin to see a population change.

“Philistines” are mentioned in the Bible right from the first book, Genesis. Yet they are actually divided into two groups: “Canaanite” Philistines, mentioned from Genesis to Joshua; and Mediterranean, “Caphtorite” Philistines, mentioned from the book of Judges on throughout the rest of the Hebrew Bible. (This division is most clearly seen in the Septuagint translation of the Bible; more on the subject of the identity of these early Canaanite Philistines can be read in our article here).

Suffice it to say that beginning sometime around the middle of the judges period, we see a Philistine influx begin to cause real problems for Israel. Chapter 10 of Judges describes the first of what would ultimately be several Philistine “oppressions” of Israel. “And the anger of the Lord was kindled against Israel, and He gave them over into the hand of the Philistines …. And they oppressed and crushed the children of Israel that year; eighteen years …” (verses 7-8).

This oppression would then be followed soon after by another, described in chapters 13-16 (relating to the story of Samson), and then another later invasion that included the destruction of Shiloh and the capture of the ark of the covenant. There were several more Philistine oppressions and conflicts during the leadership of Samuel, Saul and David.

Thus, a migration of Peleset belligerents into the Levant from the 13th to 12th centuries onward, after they were repelled from the Egyptian coast and resettled alongside Israel, fits perfectly with the biblical account of the rise of an antagonistic and oppressive Philistine population at this time. (Not to mention the now genetically proven accuracy of the biblical claim that these Mediterranean Philistines originally came from the “isle of Caphtor”—Crete; see Jeremiah 47:4, Amos 9:7 and Deuteronomy 2:20-23.)

Battle of Qarqar

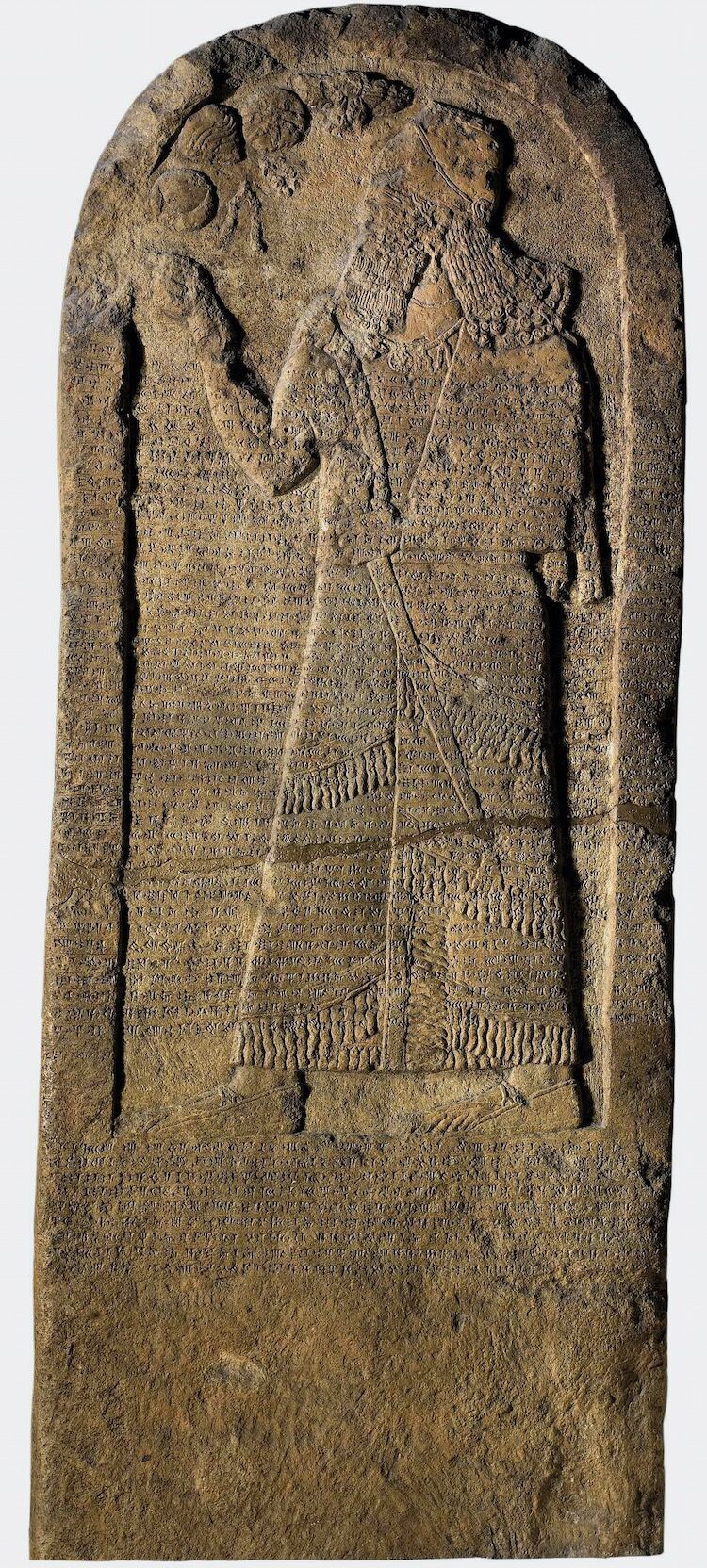

The Battle of Qarqar (853 b.c.e.), likewise viewed as one of the most important battles of the ancient world, was a major battle between a coalition of Levantine kings against the Assyrians, as detailed on the inscriptions of Assyrian King Shalmaneser iii. The belligerent Assyrian king, seeking to expand his control into the Levant, defeated the Syria-led Levantine coalition at Qarqar (northwest Syria). As recorded on Shalmaneser’s Kurkh Monolith, one of the largest divisions among the Levantine forces was an Israelite one, contributed by “Ahab the Israelite.” The Kurkh Monolith constitutes the first-known artifact to reference the biblical King Ahab.

As noted by this artifact, this famous biblical king’s contribution consisted of “2,000 chariots and 10,000 soldiers.” These numbers have been called into question by certain scholars, even theorized as a tenfold scribal error, due to the “unlikelihood” of Israel’s army being stronger than that of Syria (whose own chariot force in the battle numbered 1,200 vehicles). Yet this only fits with the biblical account, which describes Ahab’s army as repeatedly victorious against the Syrian kingdom earlier in his reign (see 1 Kings 20. The knee-jerk dismissal of the significance and strength of ancient Israel is a common modern scholarly phenomenon—for more on the debate about Ahab’s chariots, see our article here).

Yet here we run into a “problem.” The Bible records constant antagonism and fighting between Syria and Israel during Ahab’s reign. But the Kurkh Monolith attests to a joint war-effort between Syria and Israel, against Assyria. Doesn’t this contradict the biblical picture?

Actually, there’s a remarkable parallel in the chronology. The Battle of Qarqar has been dated to sometime in the final year of Ahab’s reign (based on certain external information, especially relating to Shalmaneser iii’s other inscriptions). And this is interesting for several reasons.

1 Kings 20:30-34 state that following Ahab’s final defeat of the king of Syria, he spared the king’s life, and actually “made a covenant with him.” Both kings go so far as to refer to one another as “brother” (verses 32-33). This newfound partnership included the restoration of Syrian-conquered cities to Israel and the establishment of Israelite districts in Damascus. “And they continued three years without war between Aram [Syria] and Israel” (1 Kings 22:1). These three years of peace and alliance constituted the final three years of Ahab’s reign. (At the very end of this period, Ahab turned and suddenly declared war against Syria, against the advice of the Prophet Micaiah—and during this battle, he was killed—verses 34-40.)

This unique three-year period of peace and “covenant,” or treaty, between Israel and Syria thus overlaps with the time frame for the Battle of Qarqar and helps explain why Israel and Syria sent such a large, united force (not to mention their shared interest in keeping the Assyrian Empire at bay). And the biblical account of Ahab’s former victories also helps explain why the Israelite force was more powerful than the Syrian.

Besides Syria and Israel’s alliance at this time, as recorded in the Bible, there is another tidbit of information that fits well with their ill-fated war at Qarqar.

Following Ahab’s defeat of the king of Syria three years prior, and his covenant with the king whose life he spared, he was approached by one of the “sons of the prophets.” “And he said unto him [Ahab]: ‘Thus saith the Lord: Because thou hast let go out of thy hand the man whom I had devoted to destruction, therefore thy life shall go for his life, and thy people for [or, under] his people’” (1 Kings 20:42).

And we get a dramatic picture of that from the inscriptions of Shalmaneser iii: the devastating loss of thousands of Ahab’s “people,” under the leadership of the King of Syria at Qarqar.

Perhaps this defeat even resulted in “bad blood” between Israel and Syria, leading to Ahab’s fateful decision to fight against Syria, as described in 1 Kings 22. It’s notable that for this battle, Ahab enlisted the forces of Judah—a necessary move, if he had lost such a significant part of his army at Qarqar (verse 4).

And that severe Israelite loss of military strength at Qarqar is further hinted at by the Bible’s description of Israel’s immediate loss of control over surrounding tributary nations—especially the Moabite rebellion, occurring that same year (2 Kings 3:1-5).

During the Siege of Samaria—an Assyrian Insurrection

The following event is not so much historically well-known as it is historically obscure. Yet the result of this event, which occurred at the same time as the biblical Assyrian siege of Samaria, was revolutionary in Assyrian history.

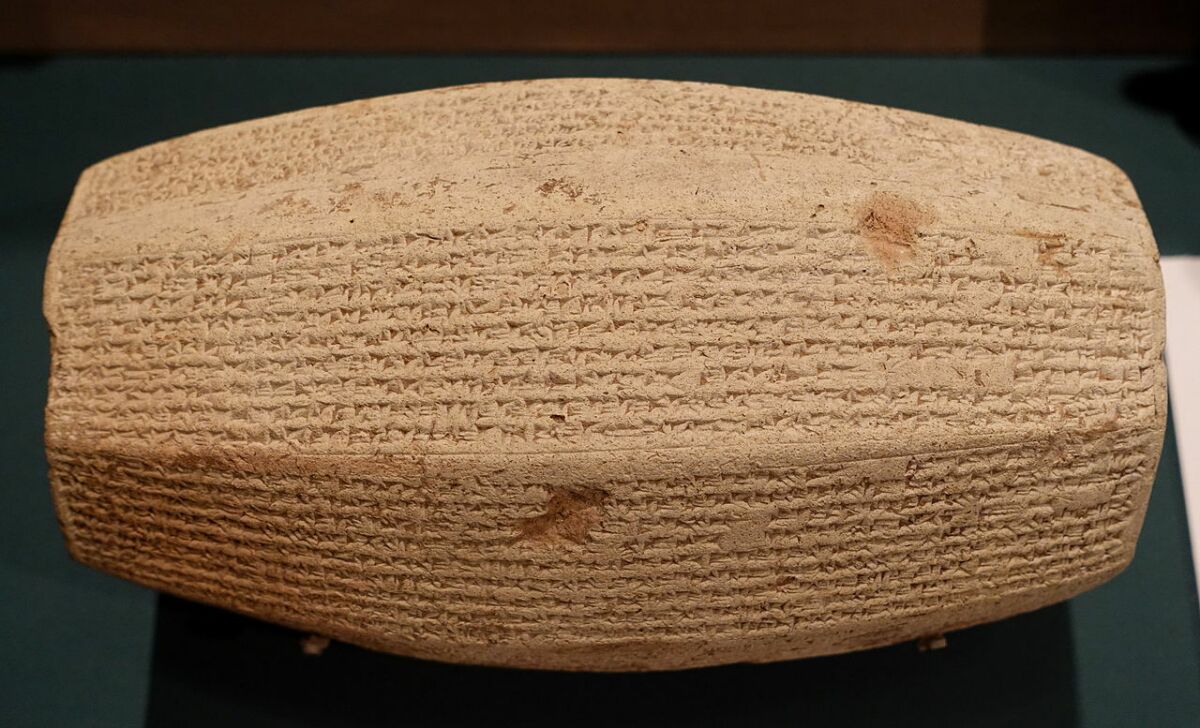

King Sargon ii (721–705 b.c.e.), founder of Assyria’s Sargonid Dynasty, is known as one of the most significant, important and powerful kings of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Yet until the late 19th century, this king was known only from a single biblical reference (Isaiah 20:1). Not even the historian Josephus mentioned him in his exhaustive writings on the history of the Jews. Shalmaneser v and Sennacherib—kings on either end of Sargon’s reign—were extremely well-known, both through classical histories and inscriptions.

Consequently, the Bible was singled out for what appeared to be either a fictional king, or for using an obscure name for another king entirely. But thanks to the 19th-century deciphering of cuneiform text and the discovery of his eponymous chief city, Dur-Sharrukin, Sargon has now been recognized as one of Assyria’s greatest kings.

Yet the general obscurity surrounding this king’s ascension to the throne of Assyria appears to be no mere accident. Bearing a name meaning “the legitimate king,” Sargon came to power in a palace coup, killing the reigning Shalmaneser v. Scholars disagree about whether Sargon was a brother of Shalmaneser or some other relative. Nonetheless, Sargon is widely regarded to be a usurper, in no way a legitimate heir to the throne. This is further indicated by certain domestic opposition during his reign.

Where this palace intrigue becomes interesting is in its connection with one of the major events in Israelite history. From 721 to 718 b.c.e., Assyria besieged and captured Samaria, capital of the northern kingdom of Israel—deporting its inhabitants to the far east and replacing them with what would become known as a “Samaritan” population (2 Kings 17). This Assyrian invasion and conquest is mentioned in numerous inscriptions and ancient historical texts.

The Bible names Shalmaneser v in connection with this conquest. Yet Sargon describes his success against Israel and deportation of Samaria’s inhabitants. Is this perhaps evidence of biblical error?

Actually, the biblical account of this period matches well with this tumultuous time in Assyria’s capital, and even hints at a certain obscurity surrounding the rightful ruler.

2 Kings 16-19 contain the names of several successive Assyrian kings as they related to Israel and Judah (Tiglath-Pileser iii, Shalmaneser v, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon)—all except for Sargon. (The single biblical mention of Sargon, in Isaiah 20:1, describes an event related to Philistia a full decade into his reign.) The Bible does name Shalmaneser v as starting the ultimately three-year campaign against the northern kingdom of Israel. As per 2 Kings 18:9: “And it came to pass in the fourth year of king Hezekiah, which was the seventh year of Hoshea son of Elah king of Israel, that Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria, and besieged it” (see also 2 Kings 17:1-5). Indeed, the siege began the same year that the Assyrian palace “insurrection” took place.

But the Bible does not mention Shalmaneser concluding the campaign. In fact, it doesn’t name the victorious Assyrian king at all. This seems somewhat peculiar for such a pivotal event, and given the several surrounding, specific mentions of Assyrian kings by name. Instead, the victor is left nameless.

2 Kings 17:6 describes the conclusion of the siege: “In the ninth year of Hoshea, the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away ….” So does 2 Kings 18:10-11: “And at the end of three years they took it … [in] the ninth year of Hoshea king of Israel, Samaria was taken. And the king of Assyria carried Israel away ….” (Technically, the definite article is not used either—thus, these passages can be equally translated “a king of Assyria.”) Ultimately, it was Sargon ii who recorded—and took credit for—the defeat and deportation of Samaria.

Thus, the Bible does not contradict the historical record in naming Shalmaneser as the king who started the campaign. Rather, the obscure references to an unnamed king of Assyria concluding the campaign help to illustrate what may well have been an ambiguous and fluid geopolitical situation in the nerve center of Assyria.

One wonders if even the Assyrian troops fighting at Samaria would have known who their leader was, three years into their siege …

Battles of Thermopylae, Salamis, Plataea …

These are some of the great battles of classical history, fought between the Persians and Greeks in the early fifth century b.c.e. These battles are only peripheral to the biblical historical account, since they took place across the Mediterranean Sea from Israel (though they feature in prophetic importance—more on that further down). But they do have a fascinating link to the book of Esther.

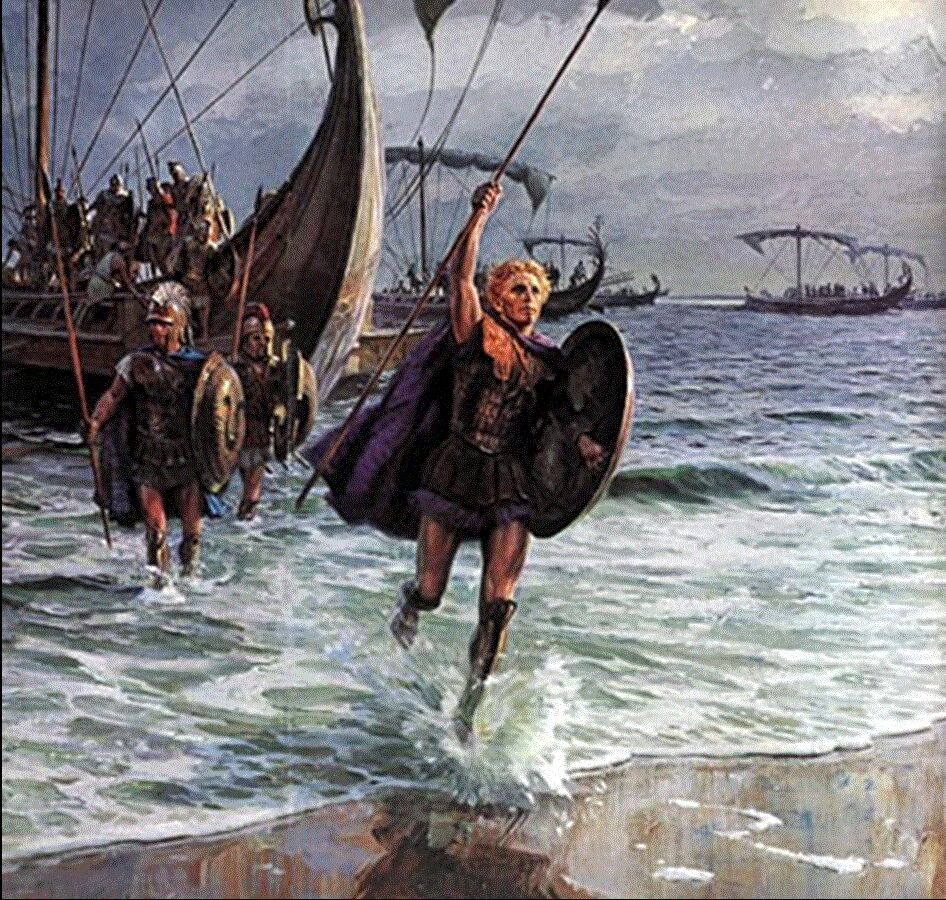

The Persian king at the center of the book of Esther, Ahasuerus, fits in name, chronology, and geographical extent of his kingdom with Xerxes i. (“Ahasuerus” as the Hebrew-transliterated, Old Persian equivalent of the name.) Xerxes i reigned from 486 to 465 b.c.e. The events of the book of Esther center around the king’s presence at his capitol Susa in year three of his reign (Esther 1:3), followed by a gap that picks up again with the king at his palace from the seventh year of his reign onward (Esther 2:16).

The significance of this gap in time, from around 483 to 479 b.c.e., can easily be missed. Yet it was within these years that the Persian king was away on campaigns against Greece.

In 481 b.c.e., Xerxes began preparing his forces for a major invasion of Europe—a massive army which included the combined forces of 46 different nations (according to the fifth-century b.c.e. Greek historian Herodotus). This campaign period (480–479 b.c.e.) marked what is known as the “Second Persian Invasion of Greece.” This period included such famous battles as that of the Thermopylae pass (of Spartan fame), Salamis, Plataea and Mycale. Ultimately, this campaign proved devastating for Xerxes, who personally led his troops, meaning that he was away from the Persian court until his seventh year as king—479 b.c.e.

And this time period “away” precisely parallels that mentioned in the Bible: A palace intrigue at Susa that only picks up from the king’s seventh year. Not only that, the return of Xerxes can be identified more specifically with the autumn of 479 b.c.e. (as explained here, by Dr. William H. Shea). This further fits with the Book of Esther, because Susa—where the story picks up—was Xerxes’ winter palace. And as for the specific “month Tebeth” of that seventh year (Esther 2:16) in which the king returned? This coincides with December-January, 479–478 b.c.e.

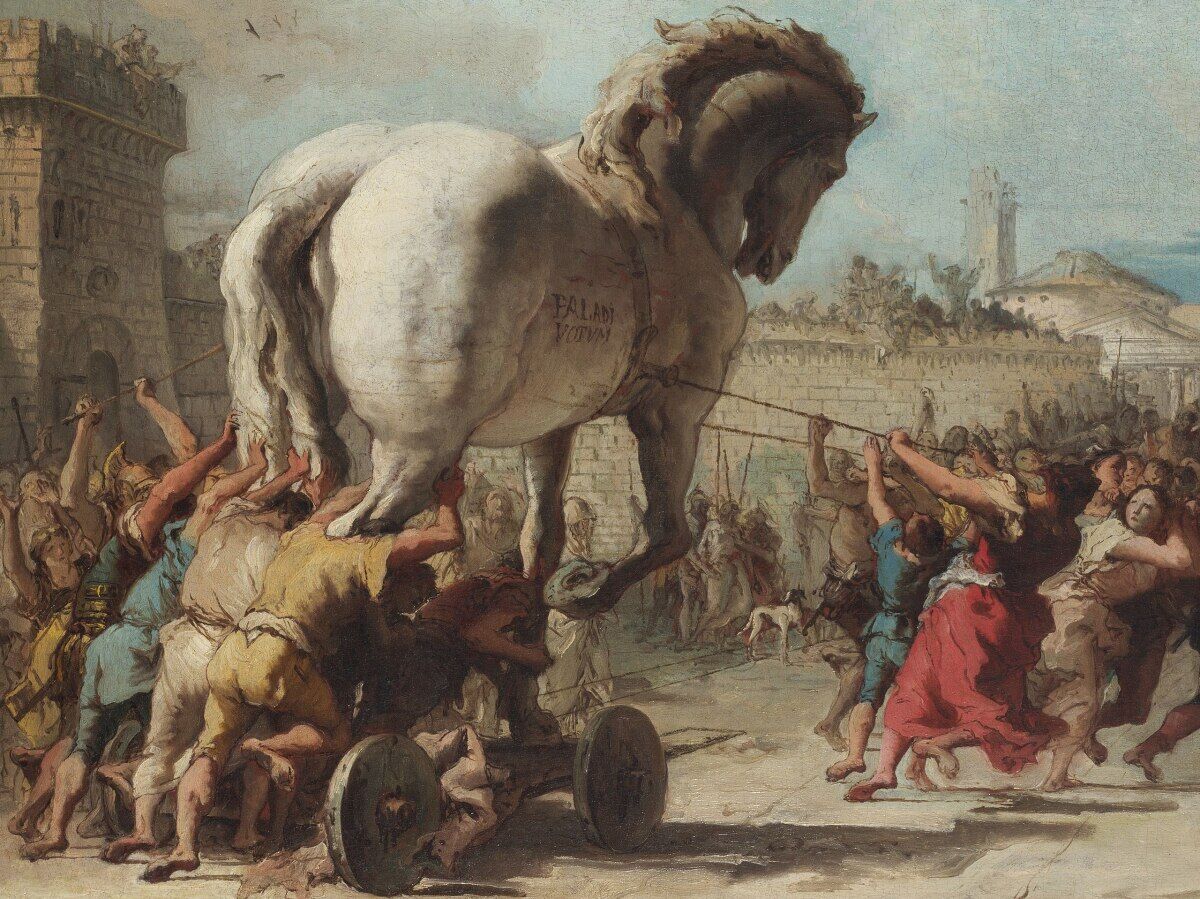

And the Battle of Troy?

Finally, we take a step further back in time again to make mention of that great battle of Greek mythology—the Battle of Troy. This inclusion may come as a surprise. After all—1,000 ships, 10-year siege, Trojan Horse, all over a stolen lover—isn’t it all just a myth?

That’s what the general consensus was, over the past several centuries. Yet archaeological evidence has been shedding light on a core genuine history behind Homer’s much-flossed epic (and not only Homer—numerous other ancient historians reference this battle; it even has a connection to the dating of the construction of Solomon’s temple—for more on that, see our article here).

The site of Wilusa, in eastern Turkey, has been identified as ancient Troy, etymologically linked to the city’s secondary name Ilios. (The name “Troy” is reflected in the general regional name Truwisa, later becoming the “Troas” mentioned in the New Testament.) A circa 13th-century b.c.e. destruction layer at Wilusa fits with the dating for the legendary battle. And there is even some evidence for the characters themselves: Hittite inscriptions name a certain unruly leader at Wilusa, Piyama-Radu, and his son Alaksandu. Could these be the Trojan King Priam and his son Alexander (more commonly known as Paris) of Homer’s epic?

Back to Judges 5 and the 13th-century passage referenced above in relation to the Battle of Kadesh.

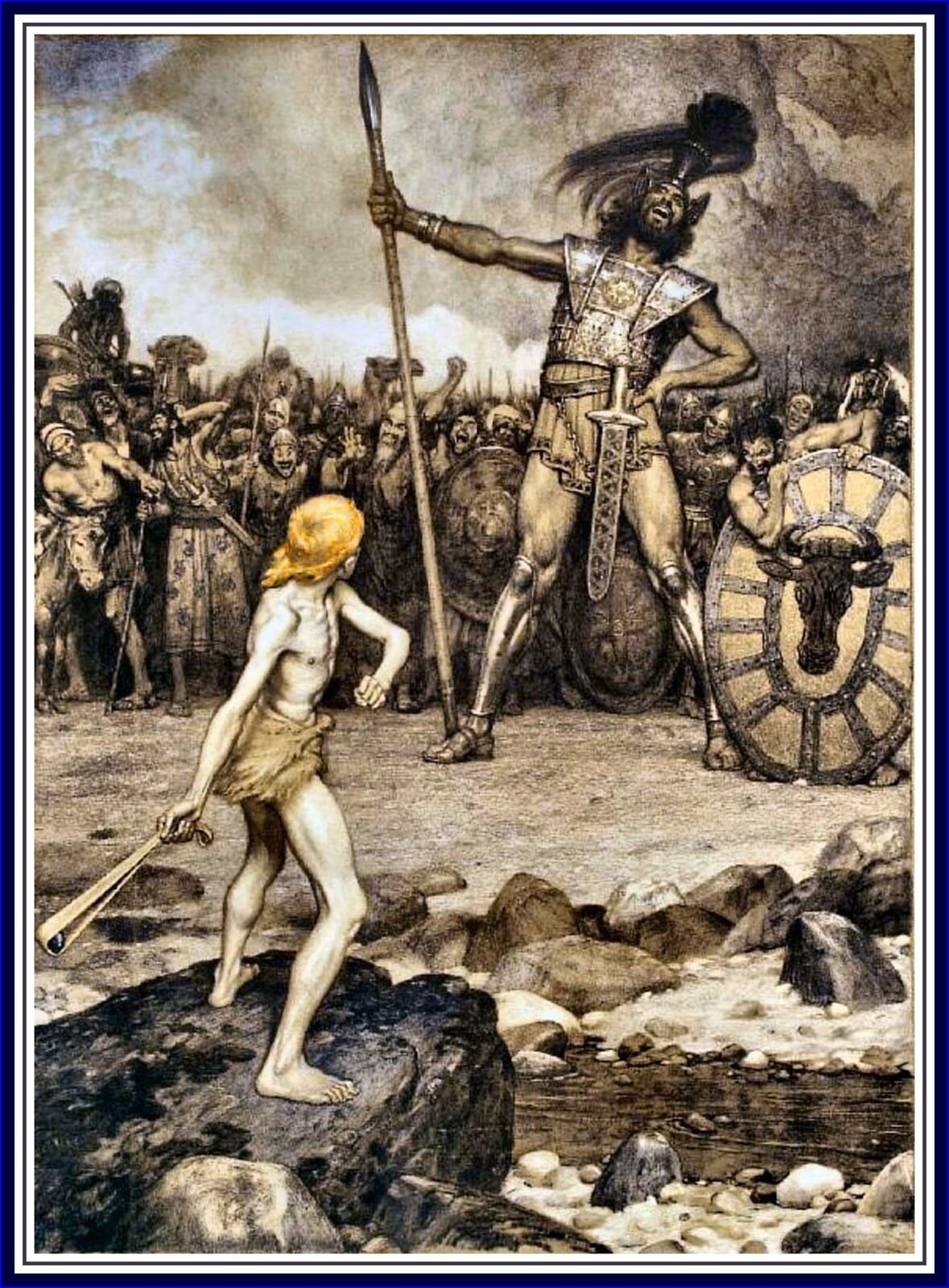

One of the Israelite tribes condemned for not joining the fight against Sisera and his chariot army was the tribe of Dan. “[W]hy did Dan remain in ships?” the Prophetess Deborah asked (verse 17; King James Version). This small sentence opens up a Pandora’s box of discussion and discovery. It is evident from this passage, and from their coastal tribal allotment, that the tribe of Dan was a seafaring tribe. The word for “ships” here is a reference to long-distance vessels. The Danites were otherwise occupied in their ships, rather than helping their fellow Israelites in this battle. Why?

There is attestation to a similarly named seafaring group with a similar culture to the Danites in Homer’s Iliad, who joined the war effort against Troy “in their ships.”

This particular people was known as Danaoi (also Danaan). These Danaoi have also been identified with a mysterious Levantine people known from inscriptions as “Denyen.” The famous late archaeologist Prof. Yigael Yadin posited that these people were one and the same as the tribe of Dan.

And archaeological excavations have only been corroborating that conclusion, pointing to a close Danite-Greek connection at this time (so much so, that Haaretz archaeology contributor Philippe Bohstrom wrote an article on the subject titled “Tribe of Dan: Sons of Israel, or of Greek Mercenaries Hired by Egypt?”). Remains from the “capital city” of the Danites, for example—Tel Dan—show heavy Greek-Mycenaean influence, in household items, weaponry, burials, idolatry, etc.

There are also numerous material and textual links between the Danite and Mycenaean worlds. Even early Irish histories (such as the 11th century Lebor Gabála Érenn) write about a certain tribe of “Danann,” who had been formerly at war with the Philistines (compare with the biblical account of the famous Danite judge and enemy of the Philistines, Samson), migrating in their sea fleet from the Mediterranean to Ireland. Ezekiel 27:19 likewise mentions “Dan also and Javan” (the biblical name for Greece) engaging in ventures at sea (kjv).

Thus: Could these biblical Danites, preoccupied “in their ships” in the late 13th century, have been one and the same as the Danaoi of the same latter part of that century—perhaps engaged in military matters elsewhere (namely at Troy)? We can only speculate. But it does fit with the general picture of this time period.

And the tribe of Dan’s focus abroad at this time fits with the wider biblical picture. Because this particular tribe—one of the most prominent and populous tribes of Israel (see Numbers 1 and 26)—almost entirely disappears from the biblical account from the judges period onward.

And as for the fateful “love story” of Helen and Paris at the center of the Battle of Troy, purported to be the cause of the entire conflict? (As the famous quip about Helen goes, she had a “face that launched a thousand ships.”) There is actually a rather fitting passage of warning in the proverbs of Solomon (this king chronologically on the scene about two centuries later).

Proverbs 6:32-35: “But the man who commits adultery is an utter fool, for he destroys himself. He will be wounded and disgraced. His shame will never be erased. For the woman’s jealous husband will be furious, and he will show no mercy when he takes revenge. He will accept no compensation, nor be satisfied with a payoff of any size” (New Living Translation).

One can’t help but think there was a specific, key example in mind at the time of this writing. And what more famous example, to this very day, than that which launched the Battle of Troy—the rage and jealousy of Helen’s husband, King Menelaus, utterly destroying the city in revenge?

‘Future’ Battles

We have here covered a handful of major battles of the ancient world. But there are several others besides, including those purported to be prophesied in the Bible.

There is Cyrus’s defeat of Babylon (Isaiah 44:24–45:3; Daniel 5); Alexander the Great’s defeat of Tyre (Ezekiel 26); his defeat of the Persian Empire (Daniel 7:6; 8:1-8, 20-22; 11:1-4); Antiochus Epiphanes’s humiliation in Egypt and his ensuing conquest and oppression of Judea (Daniel 8:9-14; 11:21-28); the Maccabean revolt, following Antiochus Epiphanes’s defiling of the land (verses 30-39); the arrival and dominance of the Roman Empire (Daniel 7:7), including the various successive phases of that empire.

This, of course, lies right at the heart of the Bible and the debate about its authority: The recognition of a God who can “[declare] the end from the beginning, And from ancient times things that are not yet done …” (Isaiah 46:10).

Such prophecies, in many instances extremely detailed, are central to the debate about when the Bible was written. Many of which, for example, are found in the book of Daniel. Were they written at the time the Bible says, before the events occurred—or long after?

For an introduction to this topic, read our article “Can We Trust the Book of Daniel?”