Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Moabites

They were ancient Israel’s eastern neighbors, dwelling in the plains of Jordan. At times their oppressors, and at other times subservient to the Israelites, these people were connected on a very physical level with the Israelites, sharing a common ancestor—Abraham’s father, Terah. They were the Moabites.

After completing the recent series, “Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities,” we now turn our attention to the Bible’s buried civilizations. Instead of individual cities, we’ll examine the wider nations and peoples that lived in them—as shown through archaeology and described in the biblical account.

Incestuous Beginnings

The Moabites had a rather awful beginning. Terah had a son named Haran, and Haran in turn had a son named Lot (Abraham’s nephew). Lot would become father to the Moabite people.

You may be familiar with the history of Sodom and Gomorrah—two cities decimated by fire from heaven as a result of their glut of sins, particularly homosexuality (Genesis 13:13; chapter 19). Lot was one of the inhabitants, living there with his wife and two daughters, who had been betrothed to two men in the city. After God sent two angels to tell Lot and his family to leave the area in order to be spared destruction, Lot, his wife, and two daughters fled. Partway into their journey, Lot’s wife looked back longingly at the city, and subsequently turned into a pillar of salt. Lot and his daughters safely made it to a mountain cave.

Lot’s daughters, having lost their betrothed husbands, believed that “there is not a man in the earth to come in unto us after the manner of all the earth. Come, let us make our father drink wine, and we will lie with him, that we may preserve seed of our father” (Genesis 19:31-32). As a result, both women became pregnant through their drunken father. The older daughter gave birth to Moab, who would become father of the Moabites. The younger gave birth to Benammi, father of the Ammonites.

The name Moab is interesting, and serves as a constant reminder of the Moabites’ incestuous beginning. According to Strong’s Concordance, Moab (pronounced “Moav” in Hebrew) is an elongated form of M’av, meaning, literally, “from father.” The specific term itself doesn’t delineate from whose father—yet of course, the tragic story makes it very clear.

A General History

Most of what we know about the Moabites comes chiefly from two sources: the Bible and a long Moabite inscription known as the Mesha Stele. This artifact will be covered in more detail later. Much still remains unknown about the Moabites.

The incident with Lot and his daughters, and the subsequent birth of Moab, would have taken place probably during the 19th century b.c.e. Our first clear view of the Moabites as a nation is during the 15th century b.c.e., as the Israelites approached the Promised Land. Under the command of Moses, the Israelites conquered the Amorites and claimed much territory, dividing it among the tribes of Reuben and Gad. However, this Amorite land previously had belonged to the Moabites, who had been conquered and evicted by Amorite King Sihon (Numbers 21:26). The politics behind this Israelite-Amorite-Moabite territorial exchange is described in full and intriguing detail in a heated dispute in Judges 11. It even is referenced, in part, on the Mesha Stele.

The original territory of Moab—taken by the Amorites, and later taken by the Reubenites and Gadites—became known even under Israelite rule as the “land of Moab.” It was this fact (and the fact that Moabites were forbidden from entering the congregation of Israel, Deuteronomy 23:3; Nehemiah 13:1) that led author Isabel Hill Elder to question whether Ruth was a Moabite after all, or rather a Reubenite, Gadite, or Levite living in what was then commonly called the “land of Moab” (Far Above Rubies).

As Israel neared the Promised Land, Balak reigned as king over the remaining territory of Moab. The sight of the oncoming Israelites terrified him—and he attempted to persuade the false prophet Balaam to pronounce a curse on the Israelites. This story, and a unique archaeological discovery that corroborates it, can be found here. While refusing to verbally curse the Israelites, Balaam instead advised that Moabite and Midianite women be sent to lead the Israelite men astray. The debauchery and paganism that followed resulted in a plague on Israel that killed 24,000 people. Yet Balak needn’t have worried about the Israelites—God had forbidden them from invading Moab (Deuteronomy 2:9; 2 Chronicles 20:10).

During the period of the judges, the Israelites were enslaved for 18 years by the rather girthy Moabite King Eglon, who governed from Jericho (Judges 3:12-30). A small ancient palatial building was found at Tel Jericho, which may have been his biblical “summer parlor.” Ehud, a Benjamite, killed Eglon and led a revolt against the Moabites, slaughtering 10,000 of them and regaining independence. It was also possibly during the time of the judges that Moab was attacked by Egypt—an inscription from Ramses ii’s Luxor temple contained the following statement: “Town that Pharaoh’s arm captured in the land of Moab: Btrt”.

After the period of the judges, Israel went to war against Moab under King Saul (1 Samuel 14:47). David sought refuge for his family among the Moabites from Saul’s persecution (1 Samuel 22:3-4), a request that was granted specially by the Moabite king. Much later, under David’s reign as king, there was war between the Moabites and the Israelites, after which the Moabites became tributaries (2 Samuel 8:2, 11-12). During the following reign of Solomon, Moabite women were taken to become part of the king’s harem (1 Kings 11:1). And during the reign of King Jehoshaphat, the Moabites joined forces with the Ammonites and inhabitants of Mount Seir to battle against the kingdom of Judah. In a miraculous outcome, God caused the belligerent armies to turn on one another, wiping themselves out (2 Chronicles 20).

The next significant time period in Moab’s history is etched onto the black surface of the Mesha Stele.

The Mesha Stele

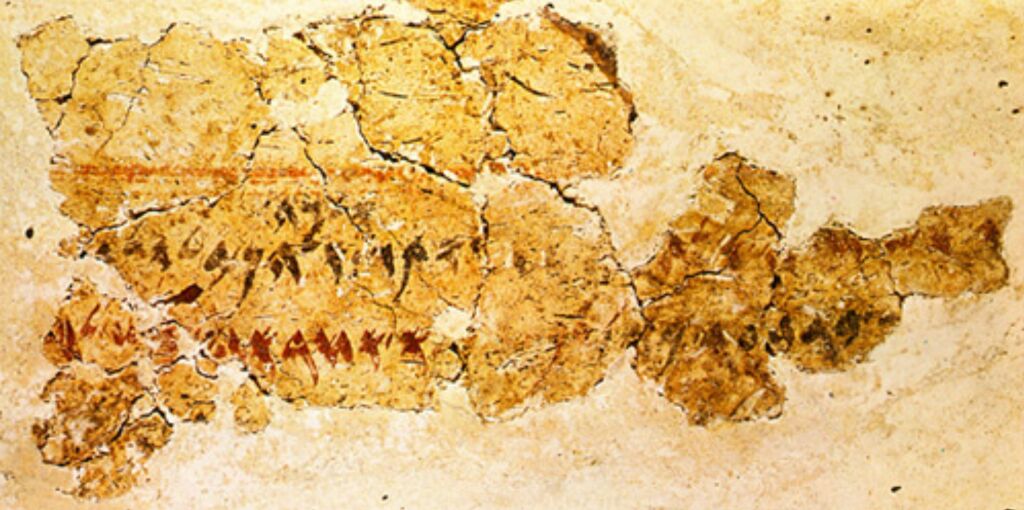

It is the greatest single Moabite artifact ever found—a large black victory stone celebrating the triumphs of the Moabite King Mesha. The long, detailed ancient text, dated within the ninth century b.c.e., was discovered in 1868 at Dhiban (Moab’s ancient capital city Dibon). Here are some key excerpts from the 34-line text:

I am Mesha, son of Chemosh(-yatti), king of Moab, the Dibonite. … I have built this sanctuary for Chemosh … for he saved me from all aggressors, and made me look upon all mine enemies with contempt. Omri was king of Israel, and oppressed Moab during many days, and Chemosh was angry with his aggressions. His son succeeded him, and he also said, I will oppress Moab …. Now Omri took the land of Madeba, and occupied it in his day, and in the days of his son, 40 years. And Chemosh had mercy on it in my time …. And the men of Gad dwelled in the country of Ataroth from ancient times, and the king of Israel fortified Ataroth. …

And Chemosh said to me, Go take Nebo against Israel, and I went in the night and I fought against it from the break of day till noon, and I took it: and I killed in all 7,000 men, but I did not kill the women and maidens, for I devoted them to Ashtar-Chemosh; and I took from it the vessels of yhwh, and offered them before Chemosh ….

This artifact parallels several biblical details, including the mention of Moabite King Mesha, Israelite King Omri, Moabite god Chemosh, and the God of Israel yhwh. The stele further mentions the tribe of Gad dwelling in ancient Moabite territory—Joshua 13 confirms this as part of Gad’s tribal allotment, and Numbers 32:34 specifically states that the Gadites built up this area of Ataroth.

The Mesha Stele (otherwise known as the Moabite Stone) shows the Moabite point of view of the following short account in 2 Kings 3:4-5:

Now Mesha king of Moab was a sheep-master; and he rendered unto the king of Israel the wool of a hundred thousand lambs, and of a hundred thousand rams. But it came to pass, when Ahab was dead, that the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel.

King Ahab was the son of Omri—and as the Mesha Stele states, it was under Omri and his unnamed son (Ahab) that Moab paid tribute. Finally the new Moabite king, Mesha, rebelled against Israelite rule. This newfound independence lasted long enough, at least, for King Mesha to celebrate with the creation of this victory stele—yet as 2 Kings 3 continues, the Moabites were later punished by the combined armies of Israel, Judah and Edom. In order to stave off the attackers, the humiliated king of Moab committed a horrible act (verse 27):

Then he took his eldest son that should have reigned in his stead, and offered him for a burnt-offering upon the wall. And there came great wrath upon Israel; and they departed from him, and returned to their own land.

Discourse: Moabite Religion and Language

As the Mesha Stele shows, Chemosh was the chief god of the Moabites. The Bible describes the Moabites specifically as the “people of Chemosh,” and calls the god an “abomination.” Worship of Chemosh was introduced to Israel by King Solomon, who was led astray by his pagan harem (1 Kings 11:1, 7). It wasn’t until the righteous King Josiah came on the scene, over 300 years later, that the place of worship Solomon had erected for Chemosh (not far from the first temple) was destroyed (2 Kings 23:13).

In 2010, the discovery of a large Moabite temple was announced. Roughly dated to the eighth century b.c.e., the temple was found stocked with approximately 300 clay figurines and vessels for use in ritual service. One clay figurine was of the bull-god, Hadad. Four stone altars were discovered at the site. The temple is the largest and most complete discovered in the region, standing three stories tall and bearing multiple chambers and an open courtyard. One of the altars had Egyptian and Assyrian-style artwork on it, showing the influence of surrounding civilizations on Moabite culture and religion.

The language used by the Moabite people was very similar to ancient Hebrew, as demonstrated especially by the Mesha Stele. The differences (such as the way words are pluralized) are minor, and Moabites would have been able to converse with their neighboring Israelites without the need of a translator.

Moab’s Downfall

From the eighth century b.c.e. onward, the Moabites were under tribute to the powerful Assyrian Empire. During the early 600s b.c.e., Moabite forces joined others from the region in sporadically attacking the kingdom of Judah. This was the time that Judah’s gradual destruction and captivity by the Babylonian Empire began. In 582 b.c.e., only three to four years after Judah’s fall, the Babylonians conquered Moab.

Unlike the Jews, the Moabites largely disappeared from history. Nehemiah records that some of the Jews who returned from captivity took Moabite wives (Nehemiah 13:23-27)—so some Moabites must have remained in the land, spared from the Babylonian destruction. What happened to the greater Moabite people remains unclear.

In the following fourth to third centuries b.c.e., the Nabataeans settled the Moabite land and ruled from Petra (a city originally within the border of Edom, south of Moab). The former Moabite territory later faced Roman rule, and then experienced the back-and-forth conquering of the Crusades. Today, the territory of Moab makes up a part of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Assyrians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Babylonians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Canaanites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Egyptians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Hittites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Kushites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Moabites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Persians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Phoenicians