Can the Book of Ruth’s Genealogy Be Reconciled With an Early Exodus?

If you’ve been following this website for very long, you’ll know that several of our articles make a case for an “early” Exodus date, during the 15th century b.c.e. The rule of kings David and Solomon is squarely dated, biblically and archaeologically, to the 10th century b.c.e. Applying to this the specified 480 years in 1 Kings 6:1 from the date of the building of the temple (widely recognized as circa 967 b.c.e.) back to the Exodus, we arrive at a date for the Exodus in the middle of the 15th century b.c.e., and an arrival in the Promised Land 40 years later, near the end of that century. Various other scriptures give us the same information, such as the 300-year-long occupation statement by Jephthah, circa 1100 b.c.e. (Judges 11:26); the overall cumulative span of the judges period; the vast 15- to 19-generation spans in 1 Chronicles 5-6; and plenty of other scriptural and archaeological evidence besides.

This, of course, stands in contrast to an alternative, popular position, that the Exodus took place some 200 years later, during the 13th-century b.c.e. Ramesside period—if not even later, during the 12th century. Proponents of this theory are necessarily dismissive of the above scriptures as “hyperbole,” simply “symbolic,” or even the ramblings of a “blubbering idiot,” Jephthah—and in large part rest their case on the description of two cities in Exodus 1:11, Pithom and Raamses, linking the latter to the 13th-century b.c.e. Pharaoh Ramesses ii. An answer to this theory highlighting the even further biblical contradictions it implies can be found in our article here.

Nevertheless, there is one other passage that could be construed as evidence of a far shorter judges period. And it’s from a rather unassuming source: a brief set of verses tucked at the very end of the book of Ruth.

Can the book of Ruth’s genealogy be reconciled with an early Exodus?

10 Generations

The book of Ruth, of course, is set during a famine epoch sometime during the period of the judges. The book is significant in establishing the heritage of Israel’s greatest king, David (and ultimately, the lineage of the Messiah). Following the veritable “love story” between Ruth and Boaz that culminates in the birth of their son, Obed, the following genealogy is tacked on at the end (Ruth 4:18-22):

Now these are the generations of Perez: Perez begot Hezron; and Hezron begot Ram, and Ram begot Amminadab; and Amminadab begot Nahshon, and Nahshon begot Salmon; and Salmon begot Boaz, and Boaz begot Obed; and Obed begot Jesse, and Jesse begot David.

Here, then, we have 10 generations from the chief anchor point of this genealogy, Perez—or Pharez, as it is translated in many other English Bibles—up to David. This Perez/Pharez was, of course, the famous son of the patriarch Judah, whose unusual conception and birth is described in Genesis 38. Ruth’s genealogy is also replicated in the book of Chronicles (1 Chronicles 2:3-5, 9-15), where Judah is added to the top of this list (thus, 11 generations).

So far, so good. But here’s where things start to get tricky. The individual roughly in the middle of this lineage, Nahshon, is specifically mentioned as having been born before the Exodus (Exodus 6:23). Indeed, this same “Nahshon the son of Amminadab” is made the princely head of his tribe immediately following the Exodus, during the initial stages of the sojourn in the wilderness (Numbers 1:7).

We can apply this information to the 480 years specified in 1 Kings 6:1, from the Exodus to the fourth year of Solomon’s reign. 480 – 4 = 476 years from the Exodus to the start of Solomon’s reign. 2 Samuel 5:4 states that David was 30 years old when he began to reign, and ruled for 40 years (seven years over Judah, 33 years over all Israel—verse 5). This means David must have been born about 406 years after the Exodus (476 – 70 = 406). This, then, leaves an entire 406-year period within which to span only five generations up to the birth of David: Nahshon, Salmon, Boaz, Obed and Jesse.

But it gets even trickier. Given that among those over 20 years old, only Joshua and Caleb came out on the other side of the 40-year sojourn (Numbers 14), Nahshon must have therefore perished in the wilderness—and logically his son, Salmon, must have been born during the wilderness sojourn. Minusing the 40-year sojourn (406 – 40), we are left with a minimum of 366 years within which to span only four generations on the scene—Salmon, Boaz, Obed and Jesse. As Zvi Ron writes in his article “The Genealogical List in the Book of Ruth: A Symbolic Approach”:

Based on this calculation, even if Salma [the alternate name for Salmon] was an infant when he entered Israel, each one of these Davidic ancestors would have had to father the next in line at a very advanced age (an average age of 91!) in order to encompass more than three-and-a-half centuries. Ibn Ezra [a renowned Middle Ages Jewish philosopher] further states that even if you say that Nahshon was less than twenty years old in the wilderness and did in fact enter Israel (in contradiction to Seder Olam), this still leaves us with an average age in the eighties for each member of the lineage to father the next in line.

But the notion that Salmon was born before the entry into Canaan does fit with other information. Such an important Judahite leader as Nahshon is nowhere mentioned at or following the entry into Canaan. And more significantly, there is another ancient genealogical list we can turn to for additional information: that of the New Testament book of Matthew.

Chapter 1 contains a genealogy from Abraham to Jesus, including this lineage from Perez/Pharez to David, and adding certain details—certain wives through which the following generations were born. Matthew 1:5 reads: “Salmon begot Boaz by Rahab, Boaz begot Obed by Ruth, Obed begot Jesse” (New King James Version). The account of the harlot Rahab at Jericho takes place immediately after the Israelites enter the Promised Land. (There is a whole separate side-study as to whether or not Salmon was actually one of the two spies within Jericho that Rahab saved—and then they her. You can read about this in detail in our article here.)

Matthew’s genealogy will carry sufficient weight for those who view the New Testament as scripture—but even for those who do not, in the words of Richard Bauckham, “For the inclusion of Rahab in the genealogy of the Messiah to have carried any weight as making a theological point … her marriage to Salma must surely have been an already accepted exegetical tradition” (“Tamar’s Ancestry and Rahab’s Marriage: Two Problems in the Matthean Genealogy.” Not to mention the author himself, Matthew, was an established Jewish publican). Bauckham proposes, however, that even this link between Rahab and Salmon can be drawn from a certain genealogical list in the Hebrew Bible alone (an article on this subject is forthcoming).

Whatever the case, this fits well with the already logical implication from the Torah—that Salmon must have been born during the wilderness sojourn. But it also applies further time constraints: It’s one thing for a man to father a child at an extremely advanced age. It’s another thing entirely for a woman (i.e. Rahab). Thus, based on this genealogical information in Matthew (the earliest genealogy we know of with additional information to that of the books of Ruth and Chronicles), various attempts to fit Salmon and Rahab within this 366-year window necessarily make Rahab as young as conceivably possible at the time of the Jericho incident (while still capable of serving as a harlot).

In sum, realistically, we are looking at bridging a gap of around 370 to 400 years with the better part of only four generations—Salmon, Boaz, Obed and Jesse.

How to solve this conundrum?

Option 1: Missing Generations

There are some knee-jerk solutions to this. One is to throw out all other consistent biblical information relating to an early Exodus, and instead hold more or less exclusively to this set of verses in Ruth as “proof” of a late-date Exodus, sojourn and judges period combined of perhaps 150–200 years or less (thus, a 13th-century b.c.e. position) before the period of the Israelite monarchy.

This would be a cop-out, though. Chiefly, in this case, because it would dispense with several other chronologies, described in the very same passages (e.g. the same introductory chapters to the book of Chronicles—chronologies which the same author was clearly aware of), that list far longer generations over the same overall span—15 generations here, 19 generations there. Ditching the greater quantity of evidence and holding on to the lesser in order to fit with a preconceived theory is, of course, never good practice (noting, again, the plethora of other scriptures that would have to be all but discarded to fit with a late-date Exodus). And at the same time, bias should be given toward the longer generations.

There’s a very good reason for that, and not only because it’s easier to rationalize a “few old men” having children, as opposed to more than a dozen consecutively virile children successively reproducing one after the other. It’s because, in contrast to our typical methodology today, it was not unusual in the ancient world to skip generations in listing genealogies, instead focusing on and highlighting select key figures within. In like manner, the biblical language of “father” and “son” is interchangeable with “grandfather” and “grandson,” and a statement of begettal likewise does not also have to mean the begettal of one’s immediately succeeding generation.

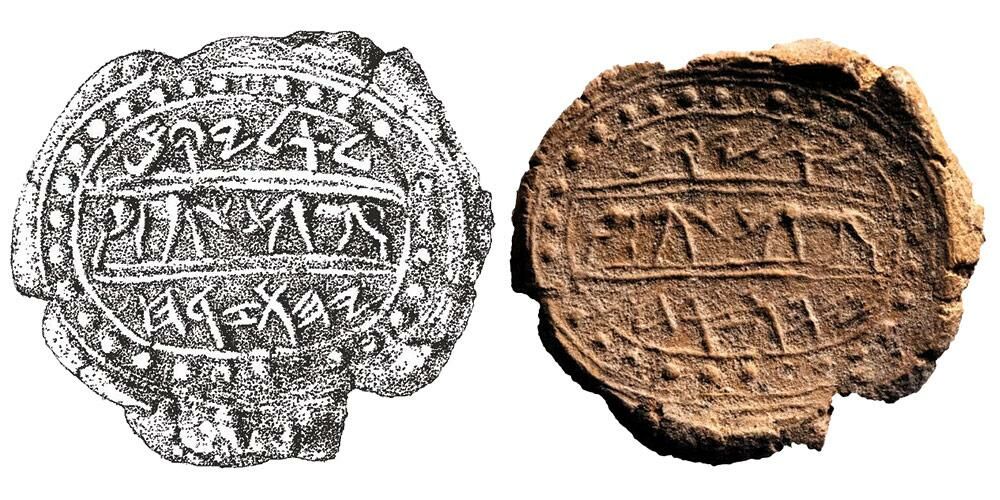

More obvious examples of this include Shem’s grandsons who are listed as his sons in 1 Chronicles 1:17, and Shallum listed as the son of Josiah in 1 Chronicles 3:15, when he is in actual fact his grandson. Genesis 48 also describes Jacob’s adoption/renaming of his grandsons Ephraim and Manasseh as his own sons. There are also certain interesting biblical archaeological discoveries highlighting this: One indicates that Isaiah 22’s Eliakim was not the direct son of Hilkiah, but perhaps a grandson (see here for more detail). Another reveals that Babylonian ruler Belshazzar was the specifically the grandson of Nebuchadnezzar (through his daughter, Nitocris), rather than his immediate son (Daniel 5).

This, then, is one potential solution to Ruth’s genealogy, and thus to the genealogies in Chronicles and the book of Matthew as well: that certain names have been skipped over in favor of the more important ones in the genealogy.

Paul Ray, in his article “The Story of Ruth: A Chronological and Genealogical Perspective,” writes: “Unfortunately, the genealogy [of Ruth 4:18-22] seems to be incomplete, with several links missing in various places (Goslinga, 556). …

Both types of genealogies [in Ruth 4 and its parallel, 1 Chronicles 2] exhibit fluidity (see Wilson, “Genealogy and History,” 27-36), omitting unimportant names, thus they seem incomplete to Westerners. … [F]luidity is a common feature in genealogies. Unimportant names were omitted, usually in the middle of the genealogy, between the names of the lineage founder (and his sons), and the then living individuals at the end.

The above-cited Zvi Ron essentially agrees with this perspective, believing that certain generations must have been skipped. He tends to place the “skipped” generations as most likely following Salmon, and/or represented by his place in the genealogy. Ron writes:

Salma’s role as a representative of many unmentioned generations can also be seen in his position in the lineage. The Nahshon-Salma transition is found in the exact middle, covering the shift between the first five ancestors and the last five. It also covers the transition from wandering in the wilderness to entering the Land of Israel, from Mosaic to post-Mosaic times.

While it may seem unusual to view Salma as a representative of many unlisted generations, this understanding resolves the chronological problem that the genealogy raises and fits in with the idea that the lineage itself is written in a symbolic style.

This may be seen in the extremely peculiar manner in which Salmon is named in Ruth 4. Though his name is typically translated both times into English as “Salmon,” the first is literally, in the Hebrew, Salma—followed by Salmon. Thus, “Nahshon begot Salma; and Salmon begot Boaz …” (verse 20-21). At this point, Ron turns to the rabbinic Midrash tradition:

In Ruth Rabbah, 8:1, the Midrash asks why Salma is called Salma when he is mentioned as the son of Nahshon, but his name is changed to Salmon when he is listed as the father of Boaz. The answer given is that the name Salmon is meant to evoke the word sulam (ladder), to indicate that “up until this point it is a ladder for princes, from this point in the lineage onward it is a ladder for kings.” We can view Salma as a representative of many missing generations in the lineage, called in the Midrash the “ladder for princes” before the transitional mid-point, and the “ladder for kings” after.

Still, the 1 Chronicles 2 genealogy has this “Salma” spelled exactly the same in both instances, as son of Nahshon and as father of Boaz. (The difference in spelling in Ruth may easily be explained as this individual having been born Salma, and by the time of his fatherhood, the name having being changed to Salmon—note several parallel examples of this, such as Abram to Abraham, Sarai to Sarah, Hoshea to Joshua.) And based on the information contained in Matthew’s genealogy, I would propose that if there were “skipped” generations, they would be between Obed and Jesse. “Salmon begot Boaz by Rahab, Boaz begot Obed by Ruth, Obed begot Jesse“ (Matthew 1:5; nkjv). This listing of certain direct begettal through a specific woman makes it extremely unlikely that there were generations in between. Additionally, we know from the account in 1 Samuel that Jesse had to be David’s direct father. This therefore only leaves the Obed-Jesse connection without further specificity—and thus, more open to the possibility of including additional generations between them.

Option 2: Begettal at Advanced Ages

The other option is to dispense entirely with a finagling of the genealogy and accept it for what it is—in this case, an extremely short family line stretched out across an extremely long time period, with the successive generations conceived at exceptional ages. There are actually several points indicating that this is the correct option.

One reason to think this is because the genealogy is replicated in several passages, each with their own unique features (Ruth starting the genealogy from Perez, 1 Chronicles 2 starting the genealogy from Judah, Matthew including detail about women)—but in all cases, the names of the actual successive fathers from Perez culminating in David are all precisely the same. There are no differences in transmission (such as is the case with the above-mentioned Shem and Josiah), and this from completely opposite spectrums of the Bible, no less—from the early book of Ruth (which exhibits some of the earliest biblical Hebrew language, as explained in Craig Davis’s book Dating the Old Testament) to the last and latest book of Chronicles, right into the New Testament era and the book of Matthew.

Another point to consider (though this could be interpreted in a variety of ways) is Bible numerics. Certain numbers within the Bible contain great significance—particularly the numbers 7, 12 and 40. A case in point can be seen in the generations from Adam to Moses: Adding up all the lifespans for each successive individual brings us to a total number of 12,600, a biblically significant number evenly divisible by the important biblical numbers 7, 12 and 40—and even the exceptionally large numbers 300, 360, 1260 and 2520.

And the numerical significance of David’s genealogy is highlighted directly and repeatedly in Matthew 1. “All the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen generations”—of course, a multiple of seven (Matthew 1:17; this number 14 here is doubly significant, as some eagle-eyed commentators have noted: It is the numerical sum of the name David—דוד—in Hebrew). This 14-generation list can also be compared to, for example, the similarly significant genealogy of Moses—seven generations from Abraham—another example of a comparatively shorter genealogy over a longer period of time. (Regarding Matthew’s genealogy, there is plenty of separate debate about “skipped” generations further along in the chronology, beyond David—a separate study. Nonetheless, when it comes to the total number of generations from Abraham to David, there is a ring of finality—“all the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen.”)

And the special position of children born to much older fathers is somewhat of a repeat theme throughout the Bible. Oftentimes the Bible points out the favored or chosen offspring as being the younger children of men of advanced age. This is more or less directly indicated during the pre-Flood world for the likes of Seth, Lamech, Noah, and his three children. Post-Flood, the patriarch Terah begat Abraham at an advanced age (anywhere between 70 to 135—there is still significant debate about this). Abraham begat his second son Isaac at an advanced age (100). Internal biblical chronology reveals that the generations from Levi to Moses were all begotten at an advanced age.

And this exact same theme is continued through to the time of David.

‘You Have Not Gone After a Young Man’

There isn’t a great deal of biblical information for the three generations in question between Salmon and David. But we do know that at least two of the three sired the next generation at a notably advanced age: Boaz and Jesse.

In Ruth 3:10, Boaz honors Ruth for her kindness toward him, “in that you have not gone after younger men.” Boaz’s age can also be highlighted through comparison to his related kinsman and comparative “brother,” Elimelech, who was father of Ruth’s first husband (Ruth 1:2, 2:1, 3, 4:3, 9). Certain Jewish midrashic tradition therefore holds that Boaz was around the age of 80 at the time he met Ruth. (Coincidentally, for what it’s worth, the numeric sum of Boaz’s name is 79—perhaps giving a slightly different twist on the biblical refrain that God names things what they are—perhaps also by how old they are!)

A similar situation is revealed with David’s father Jesse. David was the very last of eight sons fathered by this man. In fact, so “inferior” and far down on the pecking order was David, that he was entirely overlooked (perhaps even forgotten?) when Jesse presented his elder seven sons before the prophet Samuel (1 Samuel 16). Furthermore, there is no further mention of Jesse following David’s time on the run—no mention of him on the scene during his kingship. This would indicate that Jesse had died beforehand, probably when David was between the ages of 20 and 30—and thus, when comparing this to other early biblical lifespans, the aged Jesse could quite conceivably have begotten David in his 80s or 90s (or beyond).

If these ballpark figures for Jesse and Boaz are accurate (or thereabouts), then even if the unknown-aged Obed fathered Jesse at a very young age, and Salmon fathered Boaz immediately after the incident at Jericho, this combined biblical timespan alone would discount certain of the late Exodus theory timelines—certainly the 12th century b.c.e., Ramesses iii identification—but it would also place the Exodus at very least during the unlikely, earliest years of the long and prosperous reign of Ramesses ii!

So already within the context of Ruth’s shorter generational list, we have two out of the four generations noted as spanning the judges period as individuals who begat the next generation at a very advanced age. This seems too coincidental. On this point, Ron summarizes the belief of one of Judaism’s leading medieval scholars, Rabbi Nachmanides (acronym Ramban): “Ramban, in his commentary to Genesis 46:15, also mentions that the ancestors of King David all fathered sons at a very advanced age. … Thus, the traditional rabbinic answer to the puzzle of the genealogical list in Ruth is to explain that in fact Salma, Boaz, Obed, and Jesse all fathered children while in their eighties or nineties.”

‘Presentism’—Where the Problem Really Lies?

Such ages, though, are nothing majorly unusual during this early biblical history. After all, Abraham is described fathering children from the age of 86 right on up to 100 and beyond (as indicated by Genesis 24:67–25:1-7), before dying at the age of 175. The patriarch Job—who some identify as a descendant of Jacob based on Genesis 46:13, and who in any case was on the scene around this patriarchal period based on internal information relating to Job’s friends—had many of his children at an advanced age, probably beyond 100, as indicated by a comparison of chapters 1 and 42.

One of the problems with viewing biblical history—or any history, for that matter—is that we do so through the lens of “presentism,” which the Oxford Dictionary of English defines as “uncritical adherence to present-day attitudes, especially the tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values and concepts.” Presentism is when we try to grapple with, understand and interpret the past through our view of the world as it is today.

Of course, on the flip-side, there is an application of “presentism” in which the past is viewed through the present conception of the past—for example, as informed by the latest archaeological discoveries and present scholarship. This is incredibly helpful, but only to a point—because the naturally limited field of archaeology can only go so far, or reveal so much. As such, certain discoveries can be over-extrapolated, under-extrapolated, or interpreted in numerous different ways (such as pertaining to the date of the Exodus). And continually emerging discoveries regularly shift scholars’ conclusions.

Applying this to this subject of genealogies, in light of archaeological research, it is often cited that lifespans during this period were incredibly short—with an average “life expectancy … [of] about 40 years.” This is cited by Prof. James Hoffmeier (a well-known late-date, 13th century b.c.e. Exodus proponent), among others in using this position as one of the arguments against an early Exodus, and against taking certain early biblical numbers and ages literally. Hoffmeier cites A. A. Anderson in stating that “only a few individuals would live to see their seventieth birthday” anciently. This is a curious position, however, as it is well-known that the most commonly-identified, late-date pharaoh of the Exodus—Ramesses ii (the pharaoh also posited by Hoffmeier)—reigned for 66 years and lived to an age of somewhere between 90-96 years! Compare that to the late Queen Elizabeth ii, by a good margin Britain’s longest-reigning (70 years) and longest-lived (96 years) monarch—a length of reign a gushing modern audience cites as “scarcely credible” and “mind-blowing”! Or there’s another fairly popular late-date Exodus pharaoh, Merneptah (son of Ramesses ii)—despite reigning barely a decade, he lived to the age of somewhere between 70 and 80. Then there are various ancient Egyptian texts highlighting 110 years as the “ideal” lifespan.

Needless to say, there is a stark difference between lifespan and life expectancy. The former is the length of time a human can live, which we are interested in here. The latter (as specifically cited in part by Hoffmeier, in his contribution to the book Five Views on the Exodus), refers to an estimated overall average number of years a person in a society can be expected to live. It can be dramatically altered by the likes of infant mortality, wars, plagues, poor hygiene, death in childbirth, etc.—all things far more prevalent during these early periods. Hence Ramesses ii and Merneptah coolly living double or more the (arguable) average life expectancy of the time. (This somewhat-archaeologically-skewed overall picture of ancient lifespans is aptly explained by Christine Cave in her 2018 Aeon piece “Think everyone died young in ancient societies? Think again”.)

At any rate, even viewing Ruth’s genealogy through “presentism” poses no supremely impossible difficulty (setting aside the example of Ramesses ii living longer than most in our modern, Western nations!). There are numerous modern cases of conception at extremely advanced ages. One example cited in a recent article is that of business magnate and former Formula One chief executive Bernie Ecclestone, who in 2020—just weeks before his 90th birthday—welcomed a fourth child with his third wife. Another is the famous Indian Ramjit Raghav, who had two sons—one at the age of 94, and another at 96. Another is the American Rev. James E. Smith (b. 1848), who fathered a child at the age of 102.

So, we have a case here in the genealogy of Ruth where three generations in a row must have had a child variously between the ages of 80 and 100—and at a biblical time when doing so was not supremely unusual. Is that such a big deal?

There are, of course, further cases that can be made for Ruth’s genealogy as-is. The major famine that takes place, for example—central to this story—is a good fit with the account of the lead-up to Gideon’s judgeship. Chronologically, this would be around the middle part of the judges period, during the 12th century b.c.e. (a dating in which several archaeological particulars fit Gideon’s account—see here for more detail). This matches with the Boaz-Obed crossover period of Ruth’s genealogy, also in the very middle part of these generations covering the judges period.

There are various ways that people have tried to make Ruth’s genealogy fit more comfortably within our present conceptions—trying to add missing links here or there, or simply dismissing it (or other chronological information) entirely. It would indeed be unusual to have two or three generations such as these spaced out over such a lengthy period. But even by modern standards, it is certainly not impossible. As far as I’m concerned—especially given the way such unusual generations are favored, specially numbered, and in some cases in the Bible, miraculously conceived—the genealogy of Ruth stands as-is, without need of “reconciliation” or addition.

After all, “all the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen.”