Valentine’s Day—in the Hebrew Bible?

It’s a day of cards, roses, “valentines,” winged cherubs, ubiquitous heart decorations (shaped nothing like a real heart) and romance. At least, it’s supposed to be—often it’s a day of heartbreaks. Valentine’s Day is a peculiar Christian holiday not mentioned in the New Testament—unsurprisingly, as it was instituted in honor of a third-century c.e. “saint” named Valentine.

Or was it? There is more to this holiday than meets the eye, not least the questions about Valentine’s very existence (with claims of at least three different individuals named Valentine, all martyred on February 14 of various years). Did you know that this holiday actually stems from traditions long predating Christianity? And while there is no reference to it in the New Testament, there is a particular link to events described in the Old Testament—the Hebrew Bible.

‘Your Valentine’

A stock explanation of the holiday is that a Christian priest in Rome, named Valentine, who conducted marriage ceremonies for soldiers forbidden by the state, was arrested as part of the Roman persecution of Christians. While in prison, he is said to have healed the eyesight of his jailor’s daughter, and before being executed on Feb. 14, 269 c.e., he wrote her a note signed “Your Valentine.” Two centuries later, in 496 c.e., Pope Gelasius i named Valentine a saint, marking February 14 as his holiday.

A second individual similarly associated with the holiday is Valentine of Terni—a bishop said to have been martyred on Feb. 14, 273 c.e. There are also traditions of a third “Valentine,” similarly martyred on February 14 somewhere in Africa, although almost nothing is known about this individual.

Thus today, one (or all) of these individuals are “honored” by the multibillion-dollar industry that is Valentine’s Day.

Yet the historicity of these saints named Valentine is murky at best. As Paul Bois summarized in “Who Was St. Valentine? Separating the Man From the Myth”: “[H]istorians have dismissed much of what’s been said of St. Valentine as little more than embellished hagiography ….

In fact, so little historical evidence exists on the details of Valentine’s life that historians now debate whether his legends pertain to two different saints or one St. Valentine …. So unreliable are the accounts of St. Valentine that, in 1969, the Catholic Church removed his name from the General Roman Calendar, opting to leave his liturgical celebration to local calendars.

Yet long before these “Valentines” were on the scene (putting aside the question of historicity), this very date marked a pagan, sexually hedonistic holiday for the Roman Empire: Lupercalia.

From Encyclopaedia Britannica: “St. Valentine’s Day as a lovers’ festival, the choice of a valentine and the modern development of sending valentine cards has no relation to the saint or to any incident in his life” (“Valentine, Saint,” emphasis added throughout). According to Encyclopedia Americana, St. Valentine’s day practices were “handed down from the Roman festival of the Lupercalia, celebrated in the month of February” (article, “St. Valentine’s Day”).

Will You Be My Lupercus?

Lupercalia was a Roman festival celebrated on February 15 (beginning the evening before—February 14). The origins of this specific Roman festival are unclear, but elements have been traced as far back as the sixth century b.c.e. It was a festival in worship of the god Lupercus, the deified hero-hunter of wolves, and is associated with the Roman foundational myth of Romulus and Remus, twin boys who were suckled by the she-wolf (Lupa) in the cave Lupercal (while under the protection of Lupercus).

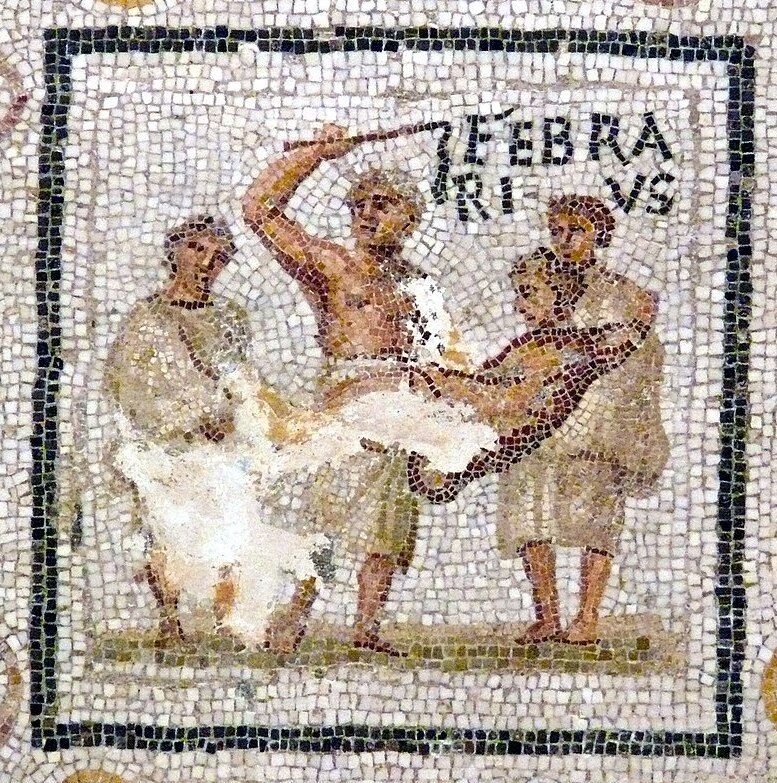

Lupercalia was a sexually charged celebration and “purification” festival, which featured matchmaking, coupling and purification rites in order to ward off evil spirits and prevent infertility. The festival began with the sacrifice of a goat (a symbol of sexuality) as well as a dog at the Lupercal cave by two naked Luperci priests. The Luperci (representing the twins Romulus and Remus) spread blood on themselves, washed it from their bodies with milk, and proceeded to cut strips from the sacrificial goats called februa. Grasping these februa, they ran through the nearby city whipping women with the thongs, who would expose themselves to receive the red blows in a “purification” bid to aid fertility and pregnancy. (The word februare means to “purify”—it is from this name, associated with these practices, that we get the month name “February.”)

From History.com’s article “Lupercalia”: “Valentine’s Day uses some of Lupercalia’s symbols … the color red, which represented a blood sacrifice during Lupercalia, and the color white, which signified the milk used to wipe the blood clean and represents new life and procreation.”

Additionally, as part of this festival’s celebration, men would choose a woman’s name from a jar at random, “coupling” with them for the festival’s duration. If the match was not considered a good one, couples would simply part ways after its conclusion—but sometimes couplings resulted in permanent marriages. (Later developments of the festival had men choose their partners by sight rather than leaving it to chance.) As summarized by Encyclopedia Americana, this practice—which continues to be popularly practiced today under the name of “exchanging valentines” (although less at random, and with the cliché, Will you be my Valentine?)—has “been handed down from the Roman festival of the Lupercalia, celebrated in the month of February, when names of young women were put into a box and drawn out by men as chance directed.”

Another related, alternate form of this Roman holiday is the lesser-known Faunalia, in honor of the forest and fertility god Faunus. Though the deity bears a different name, and was worshiped by a different class of Romans (particularly the farming community) on a slightly different date (February 13), this deity is cognate with Lupercus. Other synonymous, cognate Roman deities include Sylvanus, fertility and protector deity (particularly in respect to wolves), and Inuus, god of sexual intercourse. The first-century b.c.e. Roman historian Livy wrote, for example, that Inuus was a form of Faunus and that his worship on Lupercalia was celebrated by “naked young men [who] would run around venerating [the] Lycaean Pan, whom the Romans then called Inuus, with antics and lewd behavior” (History of Rome, 1.5.2). The fourth-century c.e. commentator Servius wrote about this god, worshiped by numerous different titles (which simply emphasize different traits):

He is called Inuus, however, in Latin, Πάν (Pan) in Greek; also Ἐφιάλτης (Ephialtes), in Latin Incubus; likewise Faunus, and Fatuus, Fatuclus. He is called Inuus, however, from going around having sex everywhere with all the animals, hence he is also called Incubus. (Commentary on the Aeneid of Vergil, 6.775)

The earlier Greek iteration of this deity, Pan (etymologically linked in name to the Latin Faun), was a cave-dwelling, Greek deity depicted with a human torso, the legs of a goat, and horns. (This motif has become familiar today, thanks to the revival of his worship among the neopagan movement—his goat-like appearance often linked to Satan himself, as depicted in Satanist statues.) Pan’s goat-human appearance was directly emulated in the later Roman Lupercus celebrations, with the Luperci priests making loincloths out of the skinned sacrificial goat. Pan is a god of sex and fertility, with a particular bent for bestiality and masturbation. Numerous obscene depictions of this god have been discovered, engaging in such sexual acts (notably discovered among the ashes of Pompeii and Herculaneum). Additionally, women who had sexual relations with multiple men were known as “Pan girls.”

As for the ubiquitous Valentine’s heart-that-looks-nothing-like-a-heart shape? A primary origin theory likewise goes back to Rome—that it is a representation of the seed-like fruit of the silphium plant—something used by the Romans as an aphrodisiac, as well as a form of birth control (serving as a contraceptive and abortifacient).

History.com summarizes: “Lupercalia is no longer a mainstream, public celebration … but some non-Christians still recognize the ancient event on February 14 (instead of Valentine’s Day) and celebrate in private.” “Non-Christians” indeed—celebrants including Satanists, among whom Lupercalia is listed on their holiday calendar.

‘Christian’ Adoption

The connections between Lupercalia and Valentine’s Day are evident. But how did this celebration come to be adopted as a “Christian” festival?

A simple answer is the popular revelry of the festival. The famous 20th-century anthropologist Ralph Linton wrote that the grafting of such festivals was a later practice “quite in line with church policy of incorporating harmless pagan folk ideas”—adopting the practices of pagan cultures as a means of drawing in more converts. (Such was the case, for example, with the Celtic Samhain becoming the dark “festival of the dead,” Halloween; the parallels between Saturnalia and Christmas; the eggs and bunnies of Eostre and Easter; and the Lupercalia transformed into St. Valentine’s Day. Such holidays are of course nowhere found in the New Testament; in contrast, the original church is described as continuing to observe the holy days commanded in the Hebrew Bible, such as Passover and Days of Unleavened Bread: 1 Corinthians 5:6-8, Acts 20:6; Pentecost: Acts 2:1, 20:16, 1 Corinthians 16:8; Atonement: Acts 27:9; and the Feast of Tabernacles: Acts 18:21.)

Anthropologist and religious historian Sir James Frazer (1854–1941) wrote that church leaders “clearly perceived that if Christianity was to conquer the world it could do so only by relaxing the too rigid principles of its Founder”—Jesus! (Studies in the History of Oriental Religions, Book 11.) The 18th-century author John Brady wrote: “For almost every pagan ceremony, some Christian rite was introduced”—including for Lupercalia, which featured the “heathen, lewd, superstitious custom of boys drawing the names of girls, in honor of their goddess” (Clavis Calendaria).

While the Roman Empire officially became “Christian” in name during the fourth century c.e., the popularity of hedonistic festivals like Lupercalia meant that the population (and leadership) were unwilling to relinquish them. As such, Pope Gelasius apparently “Christianized” the festival in 496 c.e.—at least, in name—electing to dedicate it to a “saint of lovers.” From Lavinia Dobler’s Customs and Holidays Around the World: “As far back as 496, Pope Gelasius changed Lupercalia on February 15 to St. Valentine’s Day on February 14.”

Certain priests over time attempted to give a more “holy” flavor to the traditional practice of males drawing the names of girls and coupling with them, with one variation having girls draw the names of apostles from the altar. Encyclopaedia Britannica, commenting on the pre-Christian origin of this name-drawing practice, states that this “custom [had been] introduced to England by the Romans and continued through the Christian era. In order to adapt the practice to Christianity, the church transferred it to the feast of St. Valentine” (article, “Greeting Cards”).

The 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon wrote of the “Christian” adoption of this Roman festival in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

[T]he vestiges of superstition were not so absolutely obliterated, and the festival of the Lupercalia, whose origin had preceded the foundation of Rome, was still celebrated. …

After the conversion of the imperial city, the Christians still continued, in the month of February, the annual celebration of the Lupercalia; to which they ascribed a secret and mysterious influence of the genial powers of the animal and vegetable world. The bishops of Rome were solicitous to abolish a profane custom, so repugnant to the spirit of Christianity; but their zeal was not supported by the authority of the civil magistrate: The inveterate abuse subsisted till the end of the fifth century and Pope Gelasius … appeased, by a formal apology, the murmurs of the Senate and people.

The Original Valentine

If Valentine’s Day originated as a pagan pre-Roman festival, who is this occasion really in honor of? As Gibbon wrote, Lupercalia “preceded the foundation of Rome.” Who, it might be asked, was the original “Valentine”?

The origin and identity of this holiday’s core deity is widely considered elusive, as it apparently was even to the very Romans who worshiped him. The 19th-century historian William Fowler wrote: “It is quite plain that the Roman of the literary age did not know who the god [of the Lupercalia] was” (Festivals). Encyclopedia Britannica states that “the [Lupercalia] festival itself … contains no reference to the Romulus legend [relating to the founding of Rome], which is probably later in origin.” And the fifth-century b.c.e. Greek historian Herodotus wrote of the above-mentioned Greek-worshiped deity, Pan, that “in Egypt, Pan is the most ancient of these [certain gods], and is one of the eight gods who are said to be the earliest of all” (Histories, 2.145).

It is well known that the Roman pantheon of gods is derivative of earlier pantheons. In fact, most pantheons are derivatives and can be traced back in time quite easily. The Roman pantheon is made up of and built upon the Greek deities and traditions, themselves derivative of other deities (particularly tracing back to the Mesopotamian/Babylonian pantheon). Especially famous examples include the Roman Jupiter (Greek Zeus, Mesopotamian Baal) and the Roman Venus (Greek Aphrodite, Babylonian Ishtar, or Inanna).

The cobweb of syncretic links grows further, with respect to our Lupercus/Inuus/Faunus/Sylvanus. Because as Sylvanus, this hunter-protector deity is linked by the third-century b.c.e. Roman historian Cato with the famous god of war and agricultural guardian, Mars (repeatedly calling him Mars Sylvanus). One of Mars’s primary symbols is the wolf. He also happens to be the father of Romulus and Remus.

And who else was the offspring of Mars? Cupid, born of Venus. And here we have another particular link to Valentine’s Day.

It’s a Bird! It’s a Plane! It’s … Not a Cherub

One of the most common figures associated with Valentine’s Day is a chubby winged cherub armed with a bow and arrow. But this is no ordinary cherub. This is Cupid, the winged Roman boy-god of desire and erotic love (whose name means “desire”). This chubby infant is armed with a bow and arrows, a strike from which fills the victim with uncontrollable lust. A classic motif is, of course, the heart-shape pierced through with one of Cupid’s arrows.

Regarding Cupid, his mother Venus, and their association with Lupercalia, Gerhard Marx wrote: “Lupercalia was, or became, connected with the legendary she-wolf … a synonym in Rome for a sexually available woman [indeed, the Roman word for a prostitute was lupa, meaning “she-wolf,” with brothels being named lupanars, or “wolf dens”]. So the day became connected with Venus, goddess of sexual love. Venus’s son Cupid also played an important part in this love feast” (“The Origin of St. Valentine’s Day,” 1972).

The boy-god Cupid has been appropriated in Christian iconography as representative of love. But this is quite in contrast to how he was originally seen in early Christian references: as a demon of fornication.

The earlier Greek equivalents of the Roman Mars, Venus and Cupid are Ares, Aphrodite and their son, Eros. Eros, as with Cupid, was a winged, bow-and-arrows-armed boy-god of love and sex (whose name means the same—“to desire, love”). Eros is likewise considered to be pre-Greek in origin and among the “earliest” gods. The fifth-century b.c.e. Greek author Aristophanes wrote that Eros was born from “a germless egg in the bosom of the infinite deeps … [from this] sprang the graceful Eros with his glittering golden wings, swift as the whirlwinds of the tempest. He mated in deep Tartarus with dark Chaos, winged like himself” (Birds).

The Greek word Tartarus is found once in the New Testament: It describes a location of fallen angels—demons (2 Peter 2:4). Perhaps unsurprising, therefore, the early Christian association of Cupid with the demonic realm.

Much of the direct information on these deities is limited to the first millennium b.c.e. But an intriguing link opens up to trace this “Valentine’s” deity and symbolism back further—from a completely different part of the world.

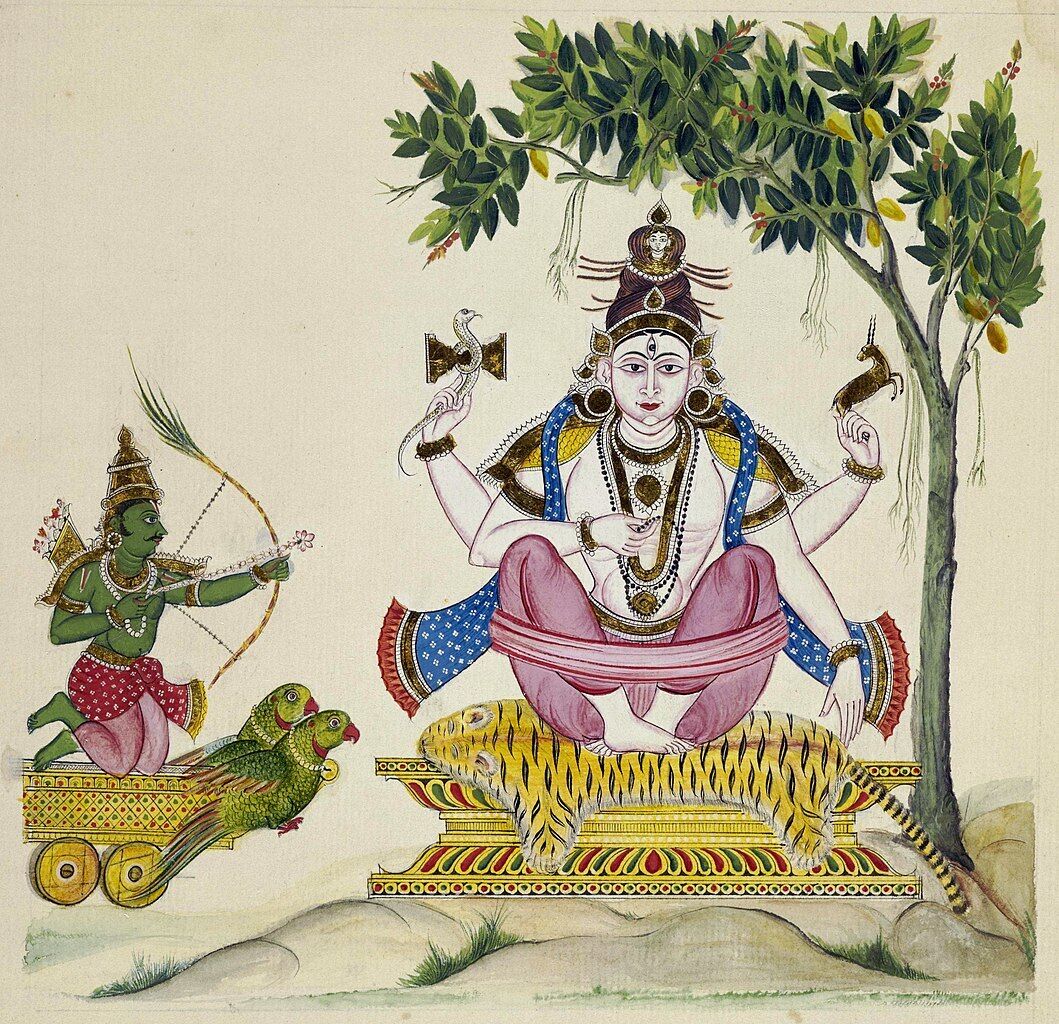

Enter Kamadeva

Kamadeva is the Hindu god of love, especially sensual or sexual love, and its associated “spells.” Kamadeva (whose name means “desire”) is depicted as a young man armed with a bow and love-arrows, riding on the wings of a bird.

Various traditions surround his worship. It is custom in Hindu weddings for the wife’s feet to be painted with pictures of Kamadeva’s bird. Ashoka trees—held as a symbol of love—are planted in the vicinity of temples, in honor of Kamadeva. Another interesting element is Kamadeva’s wife Rati (who is similarly depicted as a goddess of love, with bow and arrows), who was born of a half-goat father. Attestations of Kamadeva are found in Vedic scripture, going as far back as the second millennium b.c.e.

The Hindu origin story of Kamadeva is particularly notable. According to one form, Kamadeva descended from Dharma, who had three sons: Sama, Kama and Harsa.

To those familiar with the early biblical account, that may bring to mind the famous biblical story of the three sons of Noah from whom the Earth was repopulated, Shem, Ham (Hebrew, Kham) and Japheth. But a biblical link goes further—much further.

The ‘Valiant Hunter’

Recall Herodotus’s statement that Pan was one of the oldest deities in Egypt. He wasn’t, however, known by this name in Egypt. Herodotus was referring to (as the footnote reveals) the god Khem. The Bible actually sometimes refers to Egypt proper by the name of its ancestor, Kham—anglicized, Ham (i.e. Genesis 10:6; Psalm 78:51; 105:23; 106:22).

Genesis 10 is the passage commonly referred to as the “Table of Nations.” In it, the origins of nations are established as they relate to the descendants of the three sons of Noah. Minimal detail is given about the specific individuals in this passage—save for a certain notable descendant of this Ham, who founded the world’s first civilization centered at Babylon (the core of so many of the world’s religious pantheons). “And the sons of Ham: Cush …. And Cush begot Nimrod; he began to be a mighty one in the earth. He was a mighty hunter before [in the face of/against] the Lord; wherefore it is said: ‘Like Nimrod a mighty hunter before the Lord.’ And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel [Babylon]” (Genesis 10:6, 8-10).

The “mighty hunter Nimrod” is credited with the establishment of the first post-Flood civilization and religion of Babylon, notably leading the ill-fated construction of the tower of Babel. The ensuing “confusion of languages” event (Genesis 11) results in the ultimate dispersion of peoples around the world and, with them, certain common traditions and practices, “cultural universals” from their period of unity.

The Bible states that Nimrod was a “mighty hunter.” According to numerous extra-biblical traditions, Nimrod was an “archetypal, consummate, legendary hunter and archer,” utilized his hunting-archery skills as protector of his civilization (paralleling the reverence of Lupercus as hunter-protector). Hungarian medieval tradition, for example, records “King Nimród” as a bowhunter and siring twin sons (in parallel to the Roman foundational legend).

Persian/Islamic tradition holds that Nimrod, in his failure to reach heaven through the building of the tower of Babel, attempted to make war with God by climbing into a device lifted into the air by birds. From this flying contraption, Nimrod proceeded to shoot at God with his bow and arrows. The arrows came back down dyed red, deceiving the king into thinking he had wounded God. The earliest known example of this tradition is from the ninth-century c.e. Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari’s Tafsir—but the repetition of this account across various early sources, and in similar manner, attests to a derivation from some unknown, earlier (possibly Jewish or Hellenistic) tradition.

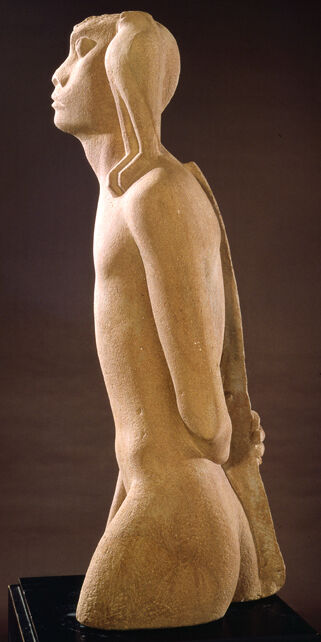

Pictured left is a famous statue of Nimrod, created by Israeli sculptor Yitzhak Danziger in 1939. These above-mentioned motifs are replicated in this work of art. The sculpture is described by the Israel Museum (where it is housed) as “a man-beast with prominent sense and sex organs, a hunter-warrior whose bow has become his backbone. Danziger took the hawk on Nimrod’s shoulder from Egyptian art, underscoring the link between his sculpture and the ancient pagan world …. Nimrod is a landmark in Israeli art; no other sculpture provoked such strong responses when it was created or continued to fascinate and engage generations of viewers in the way that Danziger’s sculpture did.”

And a link to this core biblical individual, hunter-archer and founder of Babylon can even be made here with the stubbornly recurrent Roman name Valentine. Valentine means strong, mighty or valiant (a derivative of the same word). These are all epithets fitting with the various above-mentioned iterations of the hunter-protector deity. But as we also see here, this is the epithet of Nimrod, the “original” hunter. Notice the New English Translation of Genesis 10:8-9: “Cush was the father of Nimrod; he began to be a valiant warrior [or, just as well, Valentine] on the earth. He was a mighty hunter before the Lord. (That is why it is said, ‘Like Nimrod, a mighty hunter before the Lord.’)”

“That is why it is said”—or, as the New Living Translation puts it: “his name became proverbial.”

Nimrod’s Wolf-Hunting Journey—Into Italy?

Something can even be said for a specific Nimrod-hunter connection to the center of Lupercalia worship—to Italy.

In a 1985 article titled “Valentine’s Day: Christian Custom or Pagan Pageantry?,” Dr. Herman Hoeh (who wrote at some length on this subject) stated: “The Persian author Rashid al-Din, in his History of the Franks [circa 1300 c.e.] mentions that Nimrod extended his hunting expeditions even to Italy. The Apennine mountains of Italy also bore the name the Mountains of Nembrod or Mountains of Nimrod. The hunter Nimrod pursued wolves in the Apennine mountains of Italy and acquired the title Lupercus, or ‘wolf-hunter.’”

At the base of the Apennine mountains in central-southern Italy is a town called Avella (also Abella). The tradition of the town is that it received its name from the Babylonian deity Bela/Belo, Baal, who was directly linked with Nembrot/Nimrod. This is Baal-Nimrod origin is discussed at length in the 1782 Italian-language book Avella Illustrata, by Ignazio D’Anna, quoting numerous early historians.

Italy’s Apennine mountain range makes up the backbone of the country, spanning the entire length and curling around at the southern tip into Sicily. Interestingly, the town at the northern end of the range, settled for at least 2,500 years, is called Nembro; at the southern end, in Sicily, this mountain range is called Monti Nebrodi (“Nebrodi Mountains”—note that “Nebrod” is also the early equivalent Greek spelling of the name Nimrod, as in the Septuagint). This area of Monti Nebrodi is known, at least historically, for its population of wolves.

These are all intriguing links. But what about mid-February? Why the stubbornly recurrent association of a Valentine with this time period?

The Purification—of Whom?

Here the “purification” angle of Lupercalia comes to the fore and its connection to the “mother” in the classic mother-son worship motif: Venus and her Cupid, Aphrodite and her Eros, the Egyptian Isis and her Horus—Madonna and child.

As stated, the month name “February” comes from februare, meaning “to purify”—relating to the februa whips used by the Luperci priests to “bless” and “purify” women in the town. Note that in ancient cultures, it was the practice for the mother of a male child to emerge with him, “purified,” 40 days after giving birth (see, for example, the biblical attestation of this in Leviticus 12).

Forty days prior to February 15 (counting exclusively) or February 14 (counting inclusively) brings us to January 6. In the Egyptian calendar, the winter solstice was observed on this date. The winter solstice was a key annual date in pagan cultures. This “turn” in seasonal time marked the birthday of the “sun god,” or Baal, as he is famously referred to. (Baal is another name syncretized with Pan—the Classical Dictionaries states that the Semites called Pan “Baal.”)

It is in connection to this very date that certain branches of Christianity commemorate Jesus’s birth on “January 6 in the East … especially in Egypt and Asia Minor” (Prof. Andrew McGowan, “How December 25 Became Christmas”). This, despite internal New Testament evidence showing that Jesus could not have been born on January 6—or the more popular December 25, for that matter. (Read more in our article “Christmas Trees—in the Hebrew Bible?”)

This date in mid-February, then, marked the date of the emergence of the purified “mother and child”—the emergence of Madonna and her cupid. It is for this reason that the Christian February “Candlemas” celebration, marked 40 days after the birth of Jesus—otherwise known as the “Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary”—has long been noted for a derivation from Lupercalia (especially in relation to a January 6 birth. The alternative date of Christmas, December 25, coincides with the winter solstice on the Julian calendar. Counting forward from this date, “Candlemas” is in turn celebrated on the earlier February 2—but the point of “purification,” still linked to the Roman month February, remains the same.)

Thus, quite in contrast to linking these dates with the birth and purification period of Jesus (who, based on internal New Testament information, was most likely born in the autumn), the above-mentioned Dr. Hoeh highlights these dates as associated rather with Nimrod. “The fortieth day after January 6—Nimrod’s original birthdate—takes us to February 15, the celebration of which began on the evening of February 14—the Lupercalia, or St. Valentine’s Day” (ibid).

Emerging From Babylon

From this early postdiluvian origin story within the original religious melee that was Babylon, we find an explanation for the veritable explosion of parallel traditions around the world. Pagan traditions with a constantly recurring theme of mother-son worship, reflected in the Roman Venus-Cupid, Greek Aphrodite-Eros, Hindu Rati-Kamadeva, Egyptian Isis-Horus, Babylonian Ishtar-Tammuz and Sumerian Inanna-Dumuzi myths. This motif goes much deeper than what we have covered here.

Suffice it to say that Valentine’s Day, at its core, was never really about outgoing “love,” or even a specific “saint.” And despite later efforts to put a “Christian” face on this wildly popular Roman, indelibly Babylonian-rooted festival, the New Testament itself warns against such attempts—occurring as early as the late first century c.e.—to blend a “Babylonian mystery” religion with Christianity. From Revelation 17:5, 18:2-5:

Mystery, Babylon the Great, the Mother of Harlots and Abominations of the Earth. … Babylon the great is fallen, is fallen, and is become the habitation of devils, and the hold of every foul spirit, and a cage of every unclean and hateful bird [recall Aristophanes’s summary of Eros, in Birds]. For all nations have drunk of the wine of the wrath of her fornication …. Come out of her [Babylon], my people, that ye be not partakers of her sins, and that ye receive not of her plagues. For her sins have reached unto heaven, and God hath remembered her iniquities.

As such, maybe it’s preferable not to be someone’s “Valentine.”

Article updated 05/02/24. For more in this series: