Easter—in the Hebrew Bible?

What if I told you that there is no mention of Easter in the New Testament? And conversely, that Easter traditions are mentioned in the Old Testament—the Hebrew Bible—and that it even describes Israelites celebrating “Easter” many centuries before Christianity?

Have you ever wondered where the many peculiar Easter traditions came from? What do painted eggs, bunnies and hot cross buns have to do with Jesus? Further, why is the crucifixion marked on “Good Friday” and the resurrection on “Easter Sunday”—less than two full days and nights later—when Jesus said that he would be buried for “three days and three nights”?

Christmas and Easter are the two most widely celebrated holidays on the Christian calendar. Yet as we have examined regarding Christmas, there is no mention of Easter in the New Testament, but some strikingly apt descriptions in the Hebrew Bible.

Where, then, did these Easter traditions come from?

Silence in the New Testament

But wait, Easter is mentioned in the New Testament: Acts 12:4. This is the only verse in the New Testament that uses the word “Easter”—and you’ll find it if you are using a King James Bible. It is a flagrant mistranslation; the Greek word is pascha, “Passover,” used as such 28 other times throughout the New Testament and 29 times in the Greek Old Testament. Nearly all other New Testament translations of Acts 12:4 (including the New King James Version) use “Passover” here instead. Of this verse, Adam Clarke, author of the renowned Clarke’s Commentary, wrote: “Perhaps there never was a more unhappy, not to say absurd, translation than that in our text.”

Regarding Easter, the Catholic Encyclopedia notes that “the Apostolic Fathers do not mention it … we first hear of it principally through the Controversy of the Quartodecimans [Christians who argued against it in the second century c.e.]” (article, “Easter”). The Encyclopedia Britannica states: “There is no indication of the observance of the Easter festival in the New Testament, or in the writings of the apostolic fathers. … The first Christians continued to observe the Jewish festivals, though in a new spirit, as commemorations of events which those festivals had foreshadowed” (11th edition, article “Easter”).

It may come as a surprise to learn that the earliest Christians kept the Passover dates according to instructions given in the Hebrew Bible (Leviticus 23); they also continued to keep the other festivals commanded, including Shavuot (Pentecost), Yom Kippur (Atonement), Sukkot (the Feast of Tabernacles), and even the weekly Sabbath—more on this further down.

Today, very few in the Christian world celebrate the same festivals that Jesus, the apostles, and the early church observed. Instead, celebrating the birth (Christmas) and resurrection (Easter) of Jesus are by far the two most popular traditions in Christianity. Yet ironically, neither are commanded, much less suggested, in the New Testament. What Jesus did command his disciples to commemorate was his Passover death (i.e. Luke 22:19). As the fifth-century c.e. Christian historian Socrates Scholasticus wrote of Easter: “The Savior and his apostles have enjoined us by no law to keep this feast … the feast of Easter came to be observed in each place according to the individual peculiarities of the peoples inasmuch as none of the apostles legislated on the matter. And that the observance originated not by legislation, but as a custom, the facts themselves indicate” (Historia Ecclesiastica 5.22).

Where, then, did these “customs” originate?

It’s All in the Name

Let’s start with the most obvious question: Where did the name Easter come from? The Catholic Encyclopedia continues: “The English term [Easter], according to the Ven. Bede (De temporum ratione, i, v), relates to Estre, a Teutonic goddess of the rising light of day and spring … Anglo-Saxon, easter, eastron; Old High German, ostra, ostrara, ostrarun; German, Ostern” (ibid).

The connection of the name Easter with the pagan Germanic goddess Eōstre is fairly well known. In the eighth century c.e., the monk St. Bede the Venerable wrote: “Eostur-monath has a name which is now translated ‘Paschal month,’ and which was once called after a goddess of theirs named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old observance” (De mensibus Anglorum, chapter 5; emphasis added throughout).

Of the same, Jacob Grimm wrote in his 1835 work Deutsche Mythologie: “We Germans to this day call April ostermonat, and ôstarmânoth is found as early as Eginhart [the eighth-century secretary of Charlemagne]. The great Christian festival, which usually falls in April or the end of March, bears in the oldest of ohg remains the name ôstarâ. … This Ostarâ, like the [Anglo-Saxon] Eástre, must in heathen religion have denoted a higher being, whose worship was so firmly rooted that the Christian teachers tolerated the name and applied it to one of their own grandest anniversaries.”

Little material detail is known about this ancient goddess. Her name etymologically is connected to the word East, with a connection with the rising sun and also pointing to her nature as a “spring” or “dawn” goddess—one who would retreat to the underworld in the winter and emerge in the spring.

Her worship is also traditionally associated with eggs and hares.

Of Eggs and Bunnies

For the early European pagans, eggs and hares, or rabbits, were important symbols. Edward Davies’s The Mythology and Rites of the British Druids describes the egg as a sacred emblem of the druidic order, particularly the “Ovum Anguinum, or serpent’s egg, of the Celtic priesthood.” Further, he notes that the hare, “as we learn from Caesar, was deemed sacred by the Britons.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, for its part, notes that the Easter egg “custom is found not only in the Latin but also in the Oriental Churches … [and is] probably an invention of later times. The custom may have its origin in paganism, for a great many pagan customs, celebrating the return of spring, gravitated to Easter” (section, “Easter Eggs”).

Grimm continues: “The heathen Easter had much in common with May-feast and the reception of spring. … [T]hrough long ages there seem to have lingered among the people Easter-games so-called, which the church itself had to tolerate: I allude especially to the custom of Easter eggs, and to the Easter tale which preachers told from the pulpit for the people’s amusement, connecting it with Christian reminiscences” (ibid).

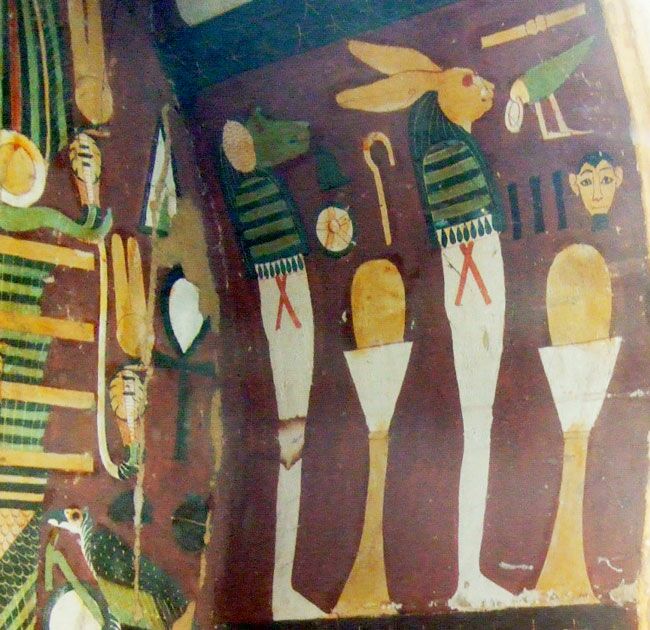

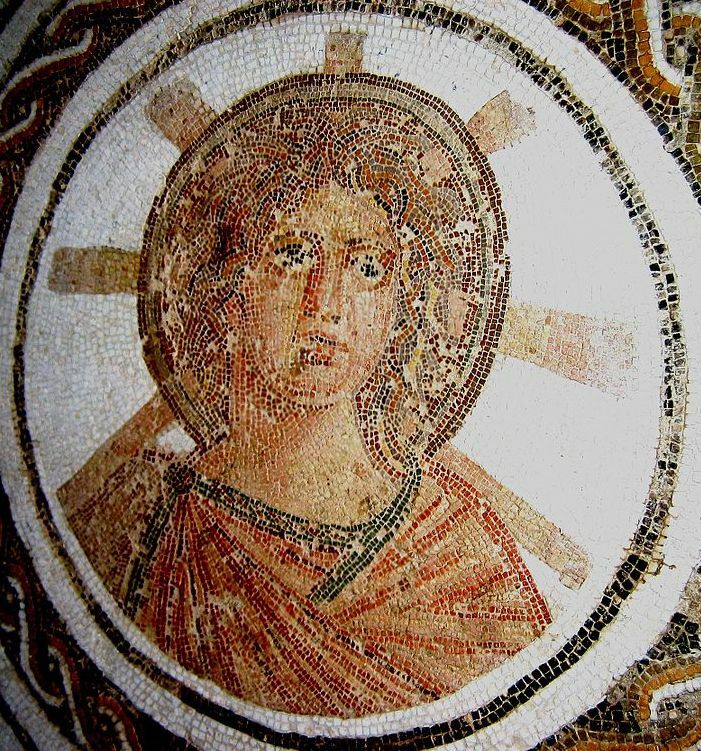

Various traditions hold that the goddess Eōstre turned a bird into a hare, which continued to have the ability to lay eggs, and would do so at Easter time. The goddess was “attended” by this hare, sometimes even depicted as flying in various artwork (as above). This association with the spring goddess is unsurprising and a fairly standard one for such a deity, given that hares and rabbits reproduce rapidly, befitting a symbol of fertility. Again from the Catholic Encyclopedia: “The Easter Rabbit lays the eggs, for which reason they are hidden in a nest or in the garden. The rabbit is a pagan symbol and has always been an emblem of fertility” (section, “The Easter Rabbit”).

Pantheon of Goddesses

In 1958, a group of altar stone fragments were discovered in northwest Germany, bearing inscriptions revealing the early existence of a related form of this goddess. These several altar inscriptions (dating to circa 200 c.e.) reference Proto-Germanic “mother goddesses” under the etymologically related name “Austriahenae.” The style of the inscriptions parallels that of Roman imperial armies, and this trove constitutes the largest number of dedications to matronae (matron/mother deities) thus-far uncovered; unfortunately, not much more is known about them.

But Eōstre and her worship can be traced back further, linguistically. Eōstre is a development of the Greek spring goddess and “goddess of the dawn,” Eos. Both names are derived from the Proto-Indo-European etymological root and “primal” dawn goddess, Hausos. It is from this root that we get not only the Greek Eos, Baltic Aushtra and later Germanic Eōstre in the West, but also the Vedic dawn goddess Ushas in the East.

In such manner, names and traditions are carried throughout history from this early center of human civilization—the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia. Study of the Germanic and Norse pantheons of gods and goddesses show close resemblance and derivation from the pantheons worshiped and transmitted across Italy, Greece, Egypt, the Levant and Mesopotamia. These pantheons typically do not generate in a vacuum, but are derivative of earlier gods and goddesses.

One of the most famous goddesses of the biblical-era Levant, worshiped by the Phoenicians, Canaanites and Israelites, bore a similar name: Astarte (the biblical “Ashtoreth”—i.e., 1 Kings 11:5). Notably, on this subject of Bede’s Eostre, the goddess Astarte, and altar inscriptions, R. Sermon states that “[w]ithin 40 km of Bede’s monastery at Jarrow … is the Roman fort of Corbridge (Corstopitum). Among the many inscriptions found at the fort is an altar dedicated to the Syrian and Phoenician fertility goddess Astarte” (article, “From Easter to Ostara: the Reinvention of a Pagan Goddess?”, subhead “Matronae Austriahenae and Astarte”).

The Phoenician goddess Astarte is herself a derivation of the chief goddess of the Babylonians and Assyrians, Ishtar. This was likewise a “dawn” goddess, due to her mythological association with the “dawn” star, the planet Venus (and yes, the goddess Venus is the Roman equivalent). The Greeks worshiped her as the famous goddess Aphrodite (a goddess that scholars likewise trace back to the Proto-Indo-European dawn goddess, Hausos). The Egyptian equivalent was Isis. Interestingly, the first-century Roman historian Tacitus describes her worship as being perpetuated within a major Germanic tribe: “Part of the Suebi sacrifice to Isis as well. I have little idea what the origin or explanation of this foreign cult is, except that the goddess’s emblem, which resembles a light warship, indicates that the goddess came from abroad” (Germania, 9).

Hausos, Ushas, Isis, Ishtar, Aushtra, Ashtoreth, Astarte, Eástre, Eostre, Eos: the similarities in name are immediately apparent. But even more remarkable are similarities in religious motifs.

Back to Eggs and Bunnies

According to the first-century c.e. scholar Hyginus, this goddess is described as hatching from an egg. “Into the Euphrates River an egg of wonderful size is said to have fallen, which the fish rolled to the bank. Doves sat on it, and when it was heated, it hatched out Venus, who was later called the Syrian goddess [Astarte] …” (Fabulae). In an Egyptian version of events, Isis is called the “egg of the goose,” and her son, Horus, is also said to have emerged from a broken egg.

The above-cited Davies, in The Mythology and Rites of the British Druids, similarly noted that “[t]his seems to have been a favourite symbol, very ancient, and adopted among many nations. … The Syrians used to speak of their ancestors, the gods, as the progeny of eggs.”

The “world egg” or “cosmic egg” is regarded as one of the most widespread symbols in pagan mysticism, found in ancient cultures from the Middle East all the way to the Pacific. James Bonwick wrote: “Eggs were hung up in the Egyptian temples. Bunsen calls attention to the mundane egg, the emblem of generative life, proceeding from the mouth of the great god of Egypt. The mystic egg of Babylon, hatching the Venus Ishtar, fell from heaven to the Euphrates. Dyed eggs were sacred Easter offerings in Egypt, as they are still in China and Europe …” (Egyptian Belief and Modern Thought).

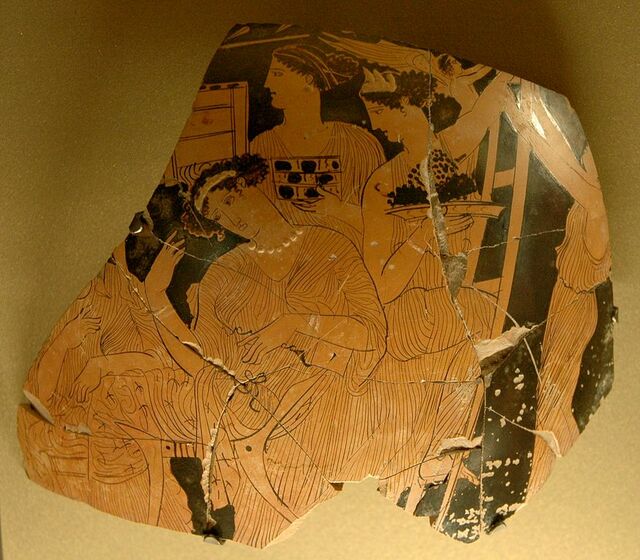

The hare was likewise a fertility symbol of the Roman Venus, and the Greek Aphrodite was accompanied by one—again, thanks to its high reproductive rate. To this end, in ancient Greece, the live animals were sometimes presented as gifts. “[I]n the Classical Greek tradition, hares were sacred to Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Meanwhile, Aphrodite’s son Eros was often depicted carrying a hare, as a symbol of unquenchable desire,” wrote T. Thompson (article, “The Roots of the Easter Bunny Explained”).

As for the Egyptians: The hare-goddess Wenut has connection to Osiris (consort of Isis and father of Horus), and Wenut is also connected to the dawn. As related in spell 720 from the Coffin Texts: “To become a dawn-god,” the deceased affirms that “I will act as one who is sent to the gods, and my voice is that of Wenut,” the hare-goddess.

‘Queen of Heaven’

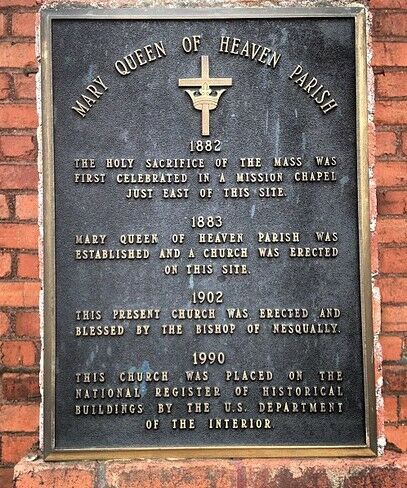

This goddess—the Roman Venus, Levantine Astarte, biblical Ashtoreth, Mesopotamian Ishtar and (in the earliest traceable form of all) the Sumerian Inanna—was worshiped in her respective countries by another specific name, “Queen of Heaven”—an archetypal title linked to her symbol, the dawn star (the planet Venus), as the brightest in the sky.

For those familiar with Christianity, that might come as a surprise—because from the fourth century c.e. onward, that became the title for Mary, mother of Jesus (and many modern churches bear the name “Our Lady, Queen of Heaven”). This name cannot be found anywhere in the New Testament, but it is in the Hebrew Bible.

“Seest thou not what they do in the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? The children gather wood, and the fathers kindle the fire, and the women knead the dough, to make cakes to the queen of heaven, and to pour out drink offerings unto other gods, that they may provoke Me” (Jeremiah 7:17-18). Here, the prophet condemns the Israelites for making “cakes” in worship of Ishtar-Astarte, the “queen of heaven.”

Is it just coincidence that to this day, one of the most ubiquitous Easter traditions is the baking of bread-cakes, or “hot cross buns”? The Encyclopedia Britannica states: “These cakes, which are now solely associated with the Christian Good Friday, are traceable to the remotest period of pagan history. Cakes were offered by ancient Egyptians to their moon-goddess …. The Greeks offered such sacred cakes to Astarte and other divinities. … In time the Greeks marked these cakes with a cross, possibly an allusion to the four quarters of the moon, or more probably to facilitate the distribution of the sacred bread which was eaten by the worshipers” (11th edition, article “Buns”).

The emphasis on cakes and the mother’s role (also related in the parallel passage, Jeremiah 44) connects even more specifically with a certain traditional event held just prior to Easter: “Mothering Sunday,” a day in which cakes are made (such as the traditional Simnel Cake, decorated with eggs) in honor of the “great mother” Mary, “queen of heaven.”

Alongside the cakes, another tradition mentioned in this same verse (Jeremiah 7:18) is the kindling and burning of fires in honor of Astarte/Ishtar. This too, curiously enough, is another famous Easter tradition—the burning of large “Easter fires”—yet again is something that, as with the cakes, cannot be found anywhere in the New Testament in relation to Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection. Of Easter fires, the Catholic Encyclopedia admits that “this is a custom of pagan origin in vogue all over Europe …. The bishops issued severe edicts against the sacrilegious Easter fires (Conc. Germanicum, a. 742, c.v.; Council of Lestines, a. 743, n. 15), but did not succeed in abolishing them everywhere. The Church adopted the observance into the Easter ceremonies …” (section, “The Easter Fire”).

This same refrain of Jeremiah 7 is found in Jeremiah 44: Just following the destruction of Jerusalem, a heated discussion took place between Jeremiah and the Jewish refugees, who refused to give up their traditions, such as making “cakes” for the “queen of heaven” (verses 15-30). And besides cakes and fires, another element is introduced: the “burn[ing of] incense to the queen of heaven” (verses 18-19; kjv). This parallels yet another particular Easter tradition—lighting incense, or especially a large incense candle (known as the “Easter candle”) embedded with incense grains.

Queen of heaven, cakes, fires, incense, a worship emphasis on mothers—none of which can be found in the New Testament relating to the crucifixion and resurrection, but all of which can be found contained in these short verses. Again, just coincidence?

The “women” element (7:18, 44:15-19) also connects another fascinating piece of the puzzle.

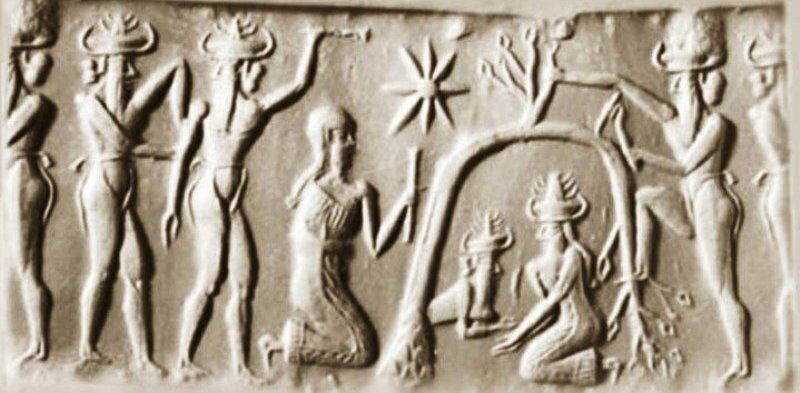

Weeping Women

The farthest back that we can trace worship of this goddess Astarte, “Queen of Heaven,” is to the third-millennium b.c.e. Sumerians. Sumer (the biblical Shinar) is often described by archaeologists and historians as the “first civilization” (fitting remarkably well with the post-Flood account in Genesis 11:1-2). The Sumerians named their goddess Inanna. (Sumerian literature actually describes her “migrating” to Sumer from Anatolia—the core location of the Proto-Hausos/Eos goddess.)

Alongside Inanna, “queen of heaven,” was her consort Dumuzi, sun-god and god of agriculture, symbolized by the evergreen tree (something that we covered in our article on Christmas trees—again, a religious item nowhere mentioned in the New Testament). Put simply, central to Inanna and Dumuzi worship was the seasons—the seasonal death and regrowth of vegetation, mythologized into the “death” of Dumuzi, Inanna’s grief and weeping for him, and his “rebirth.”

As with the spring celebrations of “rebirth,” Inanna’s weeping for the death of Dumuzi was marked through the ages by womenfolk of different regions and respective religions. The Assyrians and Babylonians replicated these traditions under the names of Ishtar and Tammuz; the Phoenicians, Syrians and Canaanites under the names Astarte and Tammuz; the Egyptians under Isis and Osiris; the Greeks under Myrrha-Aphrodite and Adonis (also Eos and Cephalus); the Romans and Phyrgians under Cybele/Nana and Attis.

At the core is a general repeating theme: A “queen of heaven” mother goddess and consort, child, or even child-consort symbolic of agriculture, who is killed (“winter”), followed by a tradition of “women weeping” in solidarity with the goddess, followed by a rebirth (“spring”). For the Sumerians, it was a “weeping for Dumuzi”; for the Levantines, a “weeping for Tammuz”; for the Greeks, a weeping for Adonis; for the Phyrgians, a weeping for Attis. These were practices especially significant for the womenfolk to engage in.

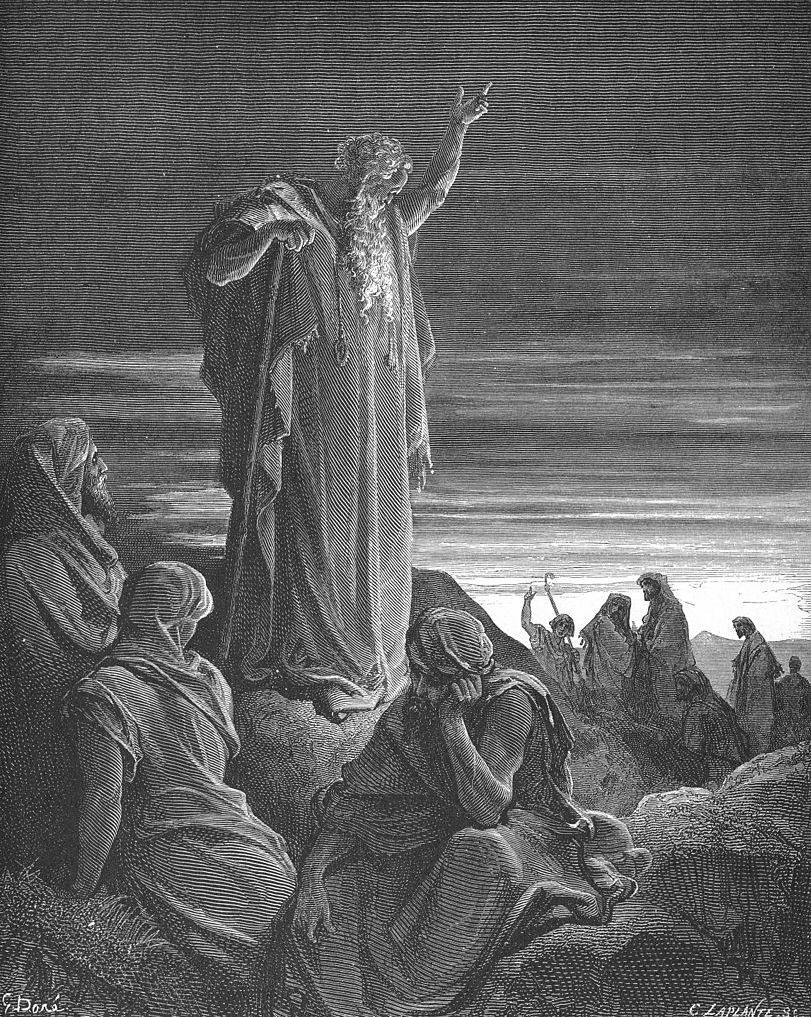

The Prophet Ezekiel (sixth century b.c.e.) described Israelite women some 1,500 years after the Sumerians still clinging to the same practices. He wrote along the same lines as Jeremiah, adding further details.

Israelites Weeping for Tammuz

“[The Lord] said also unto me: ‘Thou shalt again see yet greater abominations which they do.’ Then He brought me to the door of the gate of the Lord’s house which was toward the north; and, behold, there sat the women weeping for Tammuz” (Ezekiel 8:13-14). As with the original Sumerian worship of Inanna and Dumuzi, Ezekiel here observes Israelite women weeping for the death of Tammuz (Dumuzi).

There are more striking details in this worship surrounding Astarte and Tammuz. Ezekiel goes on: “And He brought me into the inner court of the Lord’s house, and, behold, at the door of the temple of the Lord, between the porch and the altar, were about five and twenty men, with their backs toward the temple of the Lord, and their faces toward the east; and they worshipped the sun toward the east” (verse 16).

Again, is it just coincidence to find a similar practice as part of modern Easter worship—the “sunrise service”? This tradition has a service take place outside on Easter Sunday, facing East to observe the rising sun. As summarized in Philip Schaff’s History of the Church: “The English Easter, Anglo-Saxon Oster, German Ostern, is at all events connected with the East and sunrise.”

As for the Dates …

This is where things get especially perplexing, in attempts to harmonize Easter Sunday celebrations with the New Testament account. Of his death and resurrection, the book of Matthew quotes Jesus as saying: “For as Jonas was three days and three nights in the whale’s belly; so shall the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:40)—a death and burial for three days and three nights. (See also Jonah 1:17: “Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights”; Matthew 27:63: “After three days I will rise again”; and Mark 8:31: “the Son of man must … after three days rise again.”)

Thus, the crucifixion is commemorated on Good Friday afternoon and the resurrection on Easter Sunday morning—two nights and 1½-ish days later.

Wait, what?

The math does not work out. Some try to reconcile the three days as not three entire days, but rather a period spanning at least part of Friday, Saturday, Sunday. But the “and three nights” is a clincher. Some attempt to explain this away as merely an “idiom,” again to refer generally to a period of three days, not strictly including the nights. But again, this verse has Jesus himself saying that he would be buried for “and three nights.” One wonders, on what basis are Jesus’s own words to be dismissed as not meaning what they very clearly say? Was it and two nights or and three? And this is a critical question—because as the preceding verses show, it is on the precise fulfilment of this very sign that Jesus staked his entire messiahship! (Compare also Matthew 16:4 and Luke 11:29. This also prompts the question: Could it be that in marking a crucifixion on Friday and resurrection on Sunday—with a burial period of and two nights—Jesus’s messiahship is effectively denied?)

But based on the internal calendar evidence in the New Testament, compared with the holy day calendar of the Hebrew Bible, Jesus was neither crucified on a Friday nor resurrected on a Sunday. Instead, the dates align with a Wednesday afternoon crucifixion, the day of the Passover (14th Abib—Leviticus 23:5), and a Saturday afternoon resurrection. Buried “in the heart of the earth” just before sunset Wednesday, and—with the biblical calendar count “from even unto even” (i.e. Leviticus 23:32)—Wednesday night, Thursday night and Friday night as the “three nights”; and Thursday, Friday and Saturday as the “three days,” with the resurrection just before sunset at the end of the day Saturday.

This subject would require another article to cover in detail. But there is a fascinating early historical debate connected to the applied dates of Jesus’s crucifixion and “Easter Sunday” resurrection. They are antithetical to the timeframe given in the New Testament—yet fit perfectly with the above-described, seasonal- and sun-centric veneration.

Enter the ‘Quartodeciman Controversy’

The New Testament describes Jesus and the apostles keeping the Passover as prescribed in the Torah. What was changed, from the eve of the final Passover before the crucifixion, were some of the practices observed. As the crucifixion fulfilled the symbolism of the animal sacrifice, temple sacrifices were made no longer necessary, including the killing and eating of the Passover lamb. Instead, this was replaced by the symbols of unleavened bread and wine taken on the Passover evening. Also footwashing, symbolizing humility and service, was instituted as part of the service (this is all described in Matthew 26, Mark 14, Luke 22, John 13, 1 Corinthians 11 and Hebrews 7-10).

As such, the first-century apostles continued to keep the modified Passover memorial on the same date—the 14th of the first month, Abib/Nisan (Leviticus 23:5). Some may be surprised to learn that they also continued to keep the other holy days commanded in the Torah (outlined primarily in Leviticus 23), such as the Days of Unleavened Bread (Acts 20:6, 1 Corinthians 5:6-8), Shavuot/Pentecost (Acts 2:1, 20:16, 1 Corinthians 16:8), Yom Kippur/Atonement (Acts 27:9), and Sukkot/the Feast of Tabernacles (Acts 18:21; note also Zechariah 14:16-19). They also continued to keep the weekly Sabbath (i.e. Acts 13, 17:2, 18:4, Hebrews 4:9; note also Matthew 24:20).

Some may also be surprised to find that Sunday observance is not found in the New Testament. As Cardinal James Gibbons wrote, “You may read the Bible from Genesis to Revelation, and you will not find a single line authorizing the sanctification of Sunday. The Scriptures enforce the religious observance of Saturday, a day we never sanctify” (Faith of Our Fathers).

How, then, was Easter worship—particularly Easter Sunday—instituted? Enter the Quartodeciman (“14th”) Controversy.

During the second century c.e., a great contention broke out between the churches in the East (including Jerusalem) and churches in the West (led from Rome). The churches in the East continued to keep the Passover on the 14th of Abib, no matter the day of the week it fell on. The Rome-led churches, on the other hand, wished to anchor worship to Sunday. The Encyclopedia Britannica states:

Generally speaking, the western churches [directed by Rome] kept Easter on the first day of the week, while the eastern churches … [kept Passover] on the 14th day. St. Polycarp, the disciple of St. John the Evangelist and bishop of Smyrna, visited Rome in 159 to confer with Anicetus, the bishop of that see [area], on the subject; and urged the tradition, which he had received from the apostle, of observing the 14th day …. (11th edition, article “Easter.”)

Polycarp, the church leader who had succeeded the Apostle John, was around 80 years old at the time of this confrontation; he was persecuted for refusing to adopt the Sunday observance of Easter and, shortly thereafter, was arrested and burned alive for failing to worship Caesar.

Polycarp was succeeded by his own disciple Polycrates, who likewise refused to budge on the issue of worship on the 14th. Encyclopedia Britannica continues: “About 40 years later (197) the question was discussed in a very different spirit between Victor, bishop of Rome, and Polycrates, metropolitan of proconsular Asia …. Victor demanded that all should adopt the usage prevailing at Rome ….” Polycrates wrote:

We, for our part, keep the day [Passover] scrupulously, without addition or subtraction. For in Asia great luminaries sleep [he lists several Church leaders, including the Apostle John and Polycarp] …. All of these kept the 14th day of the month … in accordance with the gospel, not deviating in the least but following the rule of the faith. … So I, my friends, after spending 65 years in the Lord’s service and conversing with Christians from all parts of the world, and going carefully through all Holy Scripture, am not scared of threats. Better people than I have said: “We must obey God rather than men.”

This dispute about observing a 14th Passover crucifixion memorial versus an Easter Sunday resurrection celebration continued on into the fourth century. The Nicene Council (325 c.e.), convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine (who was the first to make Christianity an official religion of the Roman Empire), ruled that Easter Sunday would be made the official day of worship and branded all others heretics. “[N]one hereafter should follow the blindness of the Jews,” it was decreed. The Encyclopedia Britannica describes the subsequent success that Rome had in bending Christianity to Sunday Easter worship. “The few who afterwards separated themselves from the unity of the church and continued to keep the 14th day were named Quartodecimani, and the dispute itself became known as the Quartodeciman Controversy.”

As for the weekly Sabbath in general, that same decade saw Constantine enforce Sunday worship. This was further affirmed by Rome later in the fourth century, with the decree of the Council of Laodicea: “Christians must not Judaize by resting on the Sabbath, but must work on that day, rather honoring the Lord’s day [Sunday] …. But if any shall be found to be Judaizers, let them be anathema [cursed and excommunicated] from Christ” (Canon 29). In the words of Constantine, “On the venerable day of the sun let the magistrates and people residing in cities rest, and let all workshops be closed” (Codex Justinianus, 3.12.2).

The Sun Day Problem

Sunday, then, was essential to worship in Rome. But the establishment of an “Easter Sunday” resurrection, entirely independent of Passover and its dates in the Hebrew Bible, causes dramatic calculation problems.

The 14th of Abib on the Hebrew calendar is not a fixed day of the week—Sunday, of course, is. And the New Testament is detailed in stating that Jesus was crucified and buried the day before a Sabbath, on a “preparation” day (i.e. Luke 23:54)—thus assumed to be a Friday. The reference, however, is not to a weekly Sabbath, but rather to an annual Sabbath—the “First Day of Unleavened Bread,” a high Sabbath that takes place on the 15th of Abib, the day following the Passover sacrifice on the 14th (see Leviticus 23:5-7, also John 19:31). With a Wednesday crucifixion, this annual Sabbath on the 15th would have fallen on the Thursday of the crucifixion week (something further elucidated in the original Greek of Matthew 28:1, which actually uses the plural word sabbaths—referring to both the annual Sabbath and the weekly Sabbath).

Thus, with an assumed fixed Friday crucifixion and assumed Sunday resurrection (the New Testament doesn’t say Jesus rose on Sunday, but that he was already risen by the first day of the week—Luke 24:1-6), we have the irreconcilable period of two nights and less than two full days’ burial—versus the three days and three nights described by Jesus.

But it is no accident that the Romans anchored Easter worship to Sunday (noting again the connection with sunrise services). That is, after all, why we call it Sun-day—the day historically associated with worship of the sun god—Constantine’s “venerable day of the sun.” (Despite Constantine’s popular title as “first Christian emperor,” recent archaeological discoveries have left researchers stunned as to the level of state-sanctioned paganism during his rule—as summarized in the following Biblical Archaeology Society article, “Paganism Under Constantine.”)

The Romans regarded “Sunday” as the day of the sun god, Sol (or Sol Invictus), calling it dies Solis in Latin. Notably, they also regarded December 25th as the “birthday” of this “unconquerable sun god”—this was the original Julian date of the winter solstice and applied as the birthday of Jesus. The summer solstice, in turn, was applied as the birthday of John the Baptist—“St. John’s Day.” And the timing of both Jesus’s conception and crucifixion—now entirely separated from the Hebrew calendar—became tied to the vernal equinox.

The ancient Greeks likewise named Sunday after their sun god Helios, calling it hemera Helio. It is from this Greek word for the sun that we get our term halo—the sun-disk famously used in religious paintings, often depicted over the heads of Jesus and the apostles (a religious motif again suspiciously beginning from the fourth century c.e. onward). But “halos” have been used for pagan deities as far back as Sumerian times. And the first day of the week has long been historically associated with worship of the sun—after all, the sun is indelibly connected to the first day of the Creation Week (Genesis 1:3-5).

The story of Easter, then—as well as Christmas and Sunday worship in general—is not at its core a New Testament one. It is rather the story of syncretization, with an empire retaining existing, popular customs observed from time immemorial and applying the stamp of Christianity on them. And this phenomenon is described in the New Testament.

‘Beware Babylon’

As early as the first century, we read of the apostles becoming aware of a movement to appropriate the name of Christ to existing, popular pagan customs. This syncretizing movement in the New Testament is especially identified with the region of Babylonian-influenced Samaria (2 Kings 16:23-30) and to the spiritual leader and “magician” Simon Magus (Acts 8), who according to numerous later traditions became established as a counterfeit religious leader in Rome. We read of the rise of a movement preaching “another Jesus” and “another gospel” (1 Corinthians 11:4, Galatians 1:6-7); one using the name of Christ, but not following his commands (Matthew 7:21-23).

At the end of the first century, the Apostle John wrote the following about this rising “mystery religion” with its ancient Babylonian roots:

I saw a woman [symbol of a religious entity] sit upon a scarlet coloured beast [symbol of a political power or empire] …. And upon her forehead was a name written, Mystery, Babylon the Great, the Mother of Harlots and Abominations of the Earth. … [F]or she saith in her heart, I sit a queen …. [F]or by thy sorceries were all nations deceived. (Revelation 17:3, 5; 18:7, 23)

Ultimately, John ascribed that religious deception to Satan, who “deceiveth the whole world” (Revelation 12:9). Satan is famously identified as the Lucifer (Heylel) of Isaiah 14:12—the “son of the dawn.” Sounds familiar? The Greek Septuagint calls him “Eos-foros.” Perhaps it is no coincidence, then, that Lucifer himself was worshiped in the ancient world as “son” of the dawn goddess.

In a sense, the words of John do not greatly differ to the warning of the prophet Jeremiah to the Israelites of his day. From Jeremiah 10:2-3, 5-6 (New English Translation):

The Lord says, ‘Do not start following pagan religious practices. Do not be in awe of signs that occur in the sky even though the nations hold them in awe. For the religion of these people is worthless. … And they do not have any power to help you.’

I said, ‘There is no one like you, Lord. You are great. And you are renowned for your power.’

Article updated 16/4/25. For more in this series:

Christmas Trees—in the Hebrew Bible?