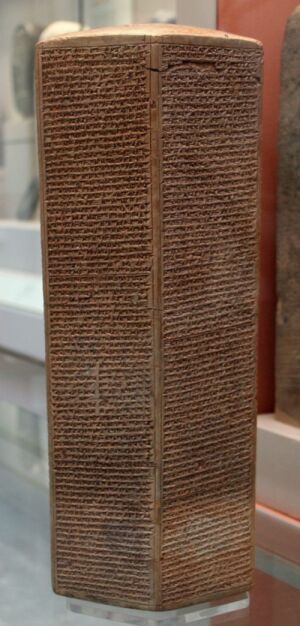

A Philistine Seal—In Ireland?

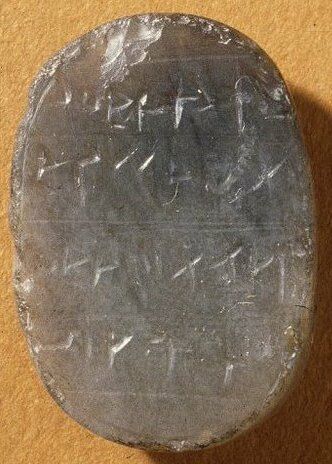

This miniature seal stamp, currently housed in the British Museum, once belonged to a royal Philistine servant who lived some 2,700 years ago. The inscription bears the following, four-tiered text:

Belonging to Abdi-Eliab

Son of Shebat

Servant of Mittitti

Son of Sidka

It’s a remarkable artifact in its own right; few Philistine inscriptions exist. But overshadowing the importance of the inscription is the fact that it turned up thousands of miles away from the Philistine homeland—in Dundrum, County Dublin, Ireland. What is the story behind this peculiar seal?

Servant to King Mittitti

First, the inscription. The seal is written in the Hebrew-Phoenician script—a script adopted by the Philistines following their migration to the coast of Israel. And though the seal gives no royal title nor nationality, it is clear from parallel Near East records that it must have been Philistine: Assyrian annals attest to two matching Philistine kings of Ashkelon—Mittinti ii and his father Sidka.

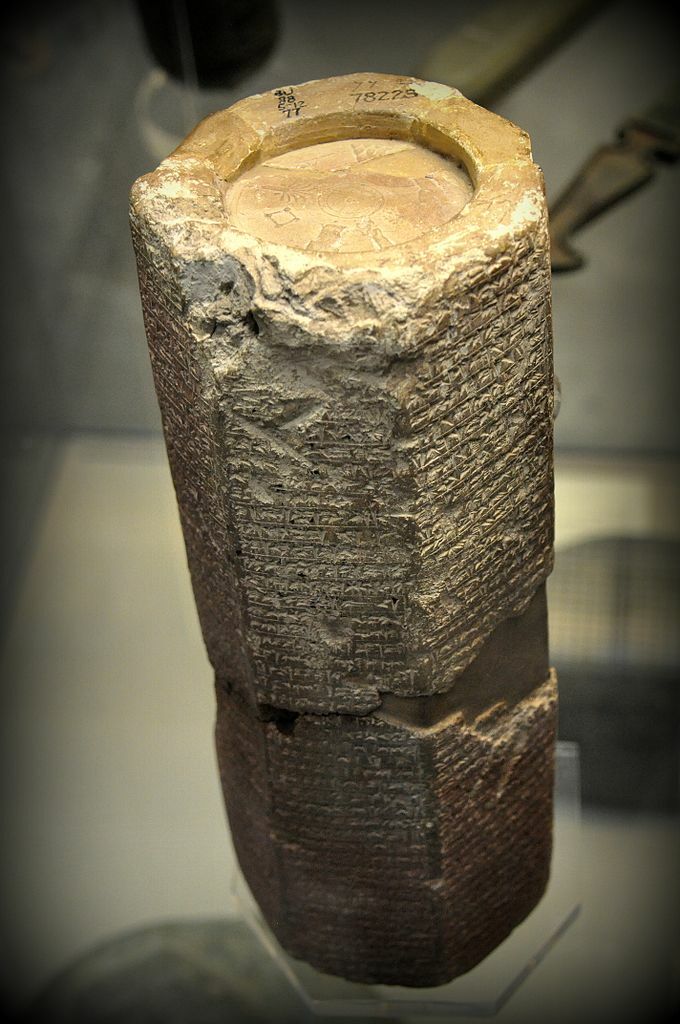

The Taylor Prism is a famous artifact that describes Assyrian King Sennacherib’s invasion of the Levant—and most significantly, his invasion of Judah during the days of biblical King Hezekiah. Numerous biblical details of the invasion have been corroborated by Sennacherib’s own account—right down to exact tribute payments. (For more information, take a look at our online exhibit “Seals of Isaiah and King Hezekiah Discovered.”) But Sennacherib’s bloody invasion also included smaller, surrounding states—including the Philistines. The Taylor Prism mentions his defeat of King Sidka (there’s some indication he may have been in an alliance with Egypt, together with Hezekiah):

But Sidka, the king of Ashkelon, who had not submitted to my yoke, the gods of his father’s house, himself, his wife, his sons, his daughters, his brothers, the seed of his paternal house, I tore away and brought to Assyria.

After the miraculous defeat of Sennacherib’s army at Jerusalem (something completely baffling to the archaeological world and conveniently omitted from Sennacherib’s otherwise detailed annals), the shamed Assyrian king returned to Nineveh, eventually to be murdered by his sons. He was succeeded by Esarhaddon (2 Kings 19:37; Ezra 4:2; Isaiah 37:38).

If Sidka’s son Mittitti had been taken away to Assyria, he was evidently brought back later and reinstated on the throne of Ashkelon. Esarhaddon records this Mittitti ii (“Mittinti” in the Assyrian annals) as paying tribute to him, alongside the famously evil Judahite King Manasseh.

I assembled the kings of the Hittites and across the river. Ba’lu, king of Tyre, Menasi, king of Judah … Mittinti, king of Askalon … all of them I sent [for tribute] … with difficulty and trouble to Nineveh, the city of my lordship, they dragged it, for the need of my palace.

The succeeding Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, also recorded receiving tribute from Mittitti ii.

Abdi-Eliab, the owner of the seal, was therefore a servant in this context to the puppet king Mittitti. We don’t know anything more about Abdi-Eliab, besides the fact that his name and that of his father, Shebat, are firmly Semitic names. The names “Abdi” and “Eliab” are found throughout the Bible, including this period in question (2 Chronicles 29:12). The word Shebat is also found several times in the Bible (though not as a personal name). It could be that Abdi-Eliab was a Hebrew servant to the Philistine king—or some other Semitic individual. (Last year, dna research showed that at this point in history, the Philistines were mixing with their neighbors; and the later book of Nehemiah condemns the Jews for their marriages to Philistine women.)

But what was Abdi-Eliab—or at least his seal—doing in Ireland?

How Did It Get to Ireland?

The first-known mention of the artifact dates to April 1849. Edward Clibborn, member of the Royal Irish Academy (ria), wrote that the seal “was found near Dundrum, in the Co. Dublin.”

Twelve years later, in 1861, the seal was sold by a “Miss Walsh” to the British Museum for £5 (where it remains today). Sir Henry Rawlinson, well connected with the British Museum and widely known as the “father of Assyriology,” wrote in 1865 that the seal “is said to have been found in Ireland, a relic, it is supposed, of the old Phoenician colonists.” In 1934, David Diringer stated that the seal had been brought to Ireland by a seafarer (see Studies on the Text and Versions of the Hebrew Bible in Honour of Robert Gordon).

None of the statements categorically state how the item arrived in Ireland, but they do at least hint that it arrived in ancient times. Of course, the knee-jerk reaction is that an ancient transmission is improbable. A Philistine seal traveling all the way to Ireland 2,700 years ago?

An alternate theory is that “Miss Walsh” was a relative of Robert Walsh (1772–1852), a historian and clergyman of County Dublin, who was well traveled and lived for a time in Constantinople. He was a known collector of coins and gems, publishing several works on archaeological discoveries, including seals and coins. Perhaps it came by way of this explorer?

The connection seems too likely to be mere coincidence—the right time period, the right “zip code,” and a sale of the item soon after the death of Walsh by a woman of the same surname. It certainly seems that it must have been in the original possession of Robert Walsh. Still, that leaves some questions. Years before Walsh’s death, the ria representative claimed that it was found near Dundrum. Walsh should have had ample opportunity—and ties to the archaeological establishment—to correct the record (after all, he himself was a member of the ria, with an interest in these matters). Further, when it was sold, the same thing was affirmed—that it was found in Ireland, with a reference to Phoenician colonists.

Perhaps it was originally in the possession of Robert Walsh, but what if it was discovered in Ireland? Walsh himself conducted excavations in Ireland and wrote of impressive discoveries—including a very early Christian amulet containing a Hebrew inscription, dug up by a potato farmer in County Cork. Could it be a similar situation for this artifact?

We cannot be sure. But one thing is sure: A 2,700-year-old transmission to Ireland would not be greatly surprising. Why not?

Sojourning in Ships

In 2017, tin ingots discovered in the Israeli port city of Haifa were chemically analyzed. The results were astounding: They revealed that the tin had been mined in Cornwall, England, before being shipped to Israel. And these were not late-era artifacts. The ingots date to the 13th to 12th centuries b.c.e. Someone, somehow, was trading between the British Isles and Israel centuries before the creation of this Philistine seal.

A number of interesting biblical passages are related to this 13th-to-12th-century b.c.e. period. One in particular describes the Israelite tribe of Dan sojourning in ships (the Hebrew indicates long-distance vessels—Judges 5:17). The same passage also describes the tribe of Asher “in his harbors” (New Living Translation). The territory of Asher included the Haifa port, and the tribe had a known association with the metal industry (Deuteronomy 33:24-25). Could this passage be describing Danite transit around the region—even as far away as Cornwall—perhaps in the business of metal trade? The archaeological record says that someone was. And Dan is also identified as a trading tribe (Ezekiel 27:19).

Parallel texts relating to this late second-millennium time period likewise describe a parallel seafaring eastern Mediterranean people known as Denyen and Danaan. The Greek poet Homer wrote about the Danaan participating in the Battle of Troy from their ships. The late Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin posited the connection between these people and the tribe of Dan.

And then there are the Irish annals.

Irish histories (note especially the 11th-century c.e. Lebor Gabála Érenn) record the migration to Ireland of an eastern Mediterranean group called Tuatha de Danann (which can be translated as “tribe of Danann”). This migration has variously been dated around this period in question—late second-millennium b.c.e. The Lebor Gabála Érenn affirms that this tribe had been constantly embattled with the Philistines. Whose territory bordered ancient Philistia? The tribe of Dan. Included among the recorded Danann migrants are numerous Semitic–Hebrew names, such as Iarbonel (“Yair, son of El”) the Soothsayer, Bethach (“Brother’s house”) and Semeon (“Heard”).

Add to that the “Tara Prince”—an Egyptian-style grave at Tara Hill, dating to the 14th century b.c.e.—as well as parallel Egyptian remains throughout the British Isles around this period (for more on this subject, check out Egyptologist Lorraine Evans’s book Kingdom of the Ark). And new dna evidence shows evidence of significant migrations to Ireland from the Middle East around four millennia ago.

Amid the archaeological evidence, historical claims and biblical links, should it be any surprise for a Philistine seal—from a state neighboring the Danite territory—to be found in Danann Ireland?