Ehud v. Eglon: Evidence for the Biblical Account

It’s one of the first significant periods of oppression for the young nation of Israel, having only just become established in the Holy Land following the Exodus. It’s a lesser-known biblical story, but still stands out thanks to a particularly graphic account of an assassination.

During the early period of the judges, Israel had been conquered by the morbidly obese king of Moab, Eglon. After 18 years of slavery, a Benjamite by the name of Ehud rose up, murdered the king, and led an armed Israelite rebellion that crushed the Moabite forces. The full story is recounted in Judges 3.

It is certainly a dramatic account. And along with several other early biblical accounts, it is often dismissed by scholars from the outset as fictional. But is there any material evidence on the ground for it? This article continues our new series on the evidence for the conflicts in the book of Judges. Let’s examine the text in detail, alongside several relevant discoveries.

Historical Context

“And the children of Israel again did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord; and the Lord strengthened Eglon the king of Moab against Israel, because they had done that which was evil in the sight of the Lord. And he gathered unto him the children of Ammon and Amalek; and he went and smote Israel, and they possessed the city of palm-trees” (Judges 3:12-14). Biblical chronology places this invasion, and the ensuing 18 years of slavery, most likely during the late 14th century b.c.e.

But this is an extremely early date, and some skeptics argue whether or not these entities even existed at this time as political powers. Could Israel and Moab have been on the scene during this period?

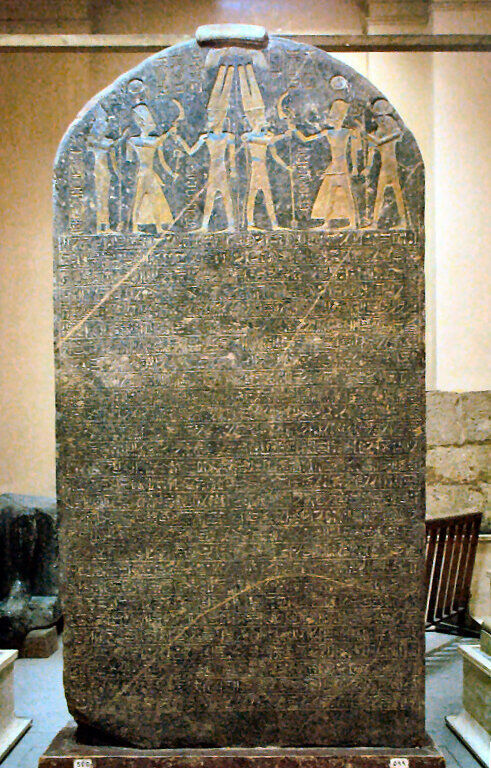

Traditional biblical chronology puts the Israelites arriving in the Promised Land around 1407 b.c.e., establishing the nation during the 14th century b.c.e. The earliest confirmed inscriptional evidence of the nation of Israel is on the Merneptah Stele, dating to the end of the 13th century b.c.e. This stele describes a defeat of the nation of Israel—thus demonstrating that the nation was already established during the 13th century b.c.e. Another Egyptian artifact, known as the Berlin Pedestal, also references the nation of Israel. The dating of this artifact is not certain, but evidence points to it being even older—perhaps dating to the 14th century b.c.e.

Moab is the other power in question. The apex of the Moabite kingdom is generally recognized from the ninth century b.c.e. onward. But inscriptional evidence mentions the nation centuries prior. A colossal statue in Luxor, Egypt, dating to the early 13th century b.c.e., details Pharaoh Ramses ii warring in “Moab,” and capturing five fortresses. Thus, Moab was also already well established and fortified by the early 13th century b.c.e.

The Balu’a Stele is an early Moabite monument, whose dating is debated—ranging from the 14th century to the 11th b.c.e.; unfortunately, the worn inscription is impossible to read. Still, it adds evidence to the early nature of the Moabite kingdom, perhaps even into the 14th century b.c.e.

Moabite archaeology is a small and comparatively unexplored field—as yet, we only have piecemeal evidence from various points throughout this nation’s history. But thanks to Egyptian inscriptions, it is clear that both Moab and Israel were already established by the 13th century b.c.e., allowing for the biblical events of Judges 3 to have taken place in the latter part of the 14th century or on into the start of the 13th century b.c.e.

And there is some evidence of this early historical animosity between Israel and Moab—a territorial dispute that Eglon may have exploited to begin his invasion. The Mesha Stele is a ninth-century b.c.e. Moabite victory inscription. It mentions that the Israelites, specifically those of the tribe of Gad, dwelt in a part of their territory “from ancient times.” This account fits perfectly with the Bible (see Numbers 21; 32:34; 33:33-34; Judges 11:14-28), which describes how this territorial dispute came about: The Israelites won this land after a battle with the Amorites, who had conquered the land from the Moabites. The tribe of Gad was given this territory, living and building within it “from ancient times”—as described on the stele.

This territorial dispute was used as a Moabite justification for invading Israel at the time of the Mesha Stele—the ninth century b.c.e. Perhaps it was also used as an excuse by Eglon, before proceeding to invade even deeper into Israel, west of the Jordan River.

Shasu Rebellion

Judges 3 highlights the main protagonists in the conflict: Moab, joined by Ammon and Amalek (eastern tribes, in and around modern-day Jordan), against the Israelites.

Some scholars believe that the early Moabites/eastern tribes are referred to as Shasu in Egyptian inscriptions. An inscription belonging to the late-14th century b.c.e. pharaoh Seti i describes a Shasu uprising in the Jordan Valley, at the very period in question. It reads:

The vanquished Shasu plan rebellion: their tribal chiefs are gathered together, rising against the Asiatics of Southern Palestine [Kharu].

“Asiatics” is simply an Egyptian term for people east of Egypt, especially the inhabitants of the Levant—Canaan/Israel. Here, we have a Jordan-based tribal coalition, rising up against a population within “southern Palestine.” This is the same general area that Eglon invaded, at the same general time period. Could this inscription be referring to the very same events of Judges 3?

A ‘City of Palm Trees’

Judges 3:14 describes Eglon’s forces invading and conquering a significant part of Israel, establishing a base at the “city of palm-trees.” This is the city of Jericho.

This is made clear by another separate reference to Jericho in 2 Chronicles 28:15: “And the men that have been mentioned by name rose up, and took the captives, … and brought them to Jericho, the city of palm-trees, unto their brethren ….” It was from this location, Jericho, that the Israelites were domineered by King Eglon.

Jericho is a well-excavated site in Israel—in fact, one of the first to have shovel put to soil. And yes, a very large body of evidence has been found for the “walls that came tumbling down”—evidence for a conquest of the city that is nothing short of a miracle (see here for details).

The Bible places the destruction of Jericho at the end of the 15th century b.c.e. Up to that point, Jericho had been a significant Canaanite city, along a vital trade route. Yet following the destruction, Jericho slips into obscurity, remaining in a general state of ruin for some 500 years. This is clearly shown by the remains at the site, and the fact that there is no mention of the city in the hundreds of Syro-Canaanite Amarna Letters from the 13th century b.c.e. (whereas dozens of other sites are named across Canaan). This backs up the biblical account, in which the Israelites were instructed to abandon the city.

But there was one notable exception during this 500-year period. In the 1930s, Prof. John Garstang discovered a peculiar building at the very top of Tel Jericho, standing above the ruins—a palatial villa that had been built during the 14th century b.c.e.

Eglon’s ‘Summer Parlour’

Judges 3:20 describes the victorious Eglon owning a “summer parlour” at Jericho (King James Version). This was some kind of temporary palatial retreat, perhaps somewhat equivalent to King Jehoiakim’s winter house (Jeremiah 36:22). In Judges, we get only the briefest description of this building positioned atop the Jericho mound. It was some kind of raised, very private building (Judges 3:20). The Hebrew word translated “parlour” in the kjv is unclear, and infers an “ascent” or “upper chamber”—again, some kind of raised, high building in the city. It had a portico/colonnaded entrance passage (verse 23), several doors and a specifically mentioned toilet (verse 24).

The peculiar palatial building discovered by Garstang’s team atop Jericho was labeled the “Middle Building.” The villa was owned by an evidently wealthy individual, as shown by the remains—including “fine china” (expensive imported pottery from Cyprus) and a cuneiform inscription (indicating the high-ranking owner of the building had a scribe). The residence itself was circa 14.5 x 12 meters. It included a long, stable-like room, a strong enclosing wall, and even an oven and hearth. Based on the remains, the residence was only in use for a brief period of time.

A 14th-century b.c.e. palace, with no existing city below to rule over. And as for the owner, no remains from this period of occupation were found in the nearby Jericho tombs—the occupant of the villa building was not given a burial in the city, as might normally be expected. All very peculiar.

But this all fits well with the biblical account of Eglon’s “summer parlour” perched atop the ruined Jericho. It fits precisely with the date and description of Eglon’s residence in Jericho. The long stable-like room may relate to the colonnaded passage leading to Eglon’s private room (verse 23). Eglon only briefly lived at the location before he was murdered, and he certainly would not have been buried in Jericho’s tombs. Who else could this building have belonged to?

It was from this vacation spot (as well as his headquarters in neighboring Moab) that Eglon domineered the servile Israelites for 18 years.

Left-handed Vengeance

Judges 3:15 reads:

But when the children of Israel cried unto the Lord, the Lord raised them up a saviour, Ehud the son of Gera, the Benjamite, a man left-handed; and the children of Israel sent a present by him unto Eglon the king of Moab.

A short discourse about Ehud. There are only three passages in the Bible referring to left-handers. They are peculiar, in that they all refer to military events, and to men specifically of the tribe of Benjamin. Some scholars have pointed out that this may be a simple play on words—after all, “Benjamin” means “son of my right hand.” But there is actually some substantial justification for this use of specifically left-handed military men.

From a modern perspective, left-handers are very desirable in sports (and are proportionally over-represented in such). This is due to a number of factors, depending on the sport. They have a unique edge in going up against an opponent typically familiar with right-hand biased opposition (i.e. a batsman going up against a pitcher or bowler). A “leftie” exploits a natural, untrained weakness.

The same holds true in hand-to-hand combat. Right-handers will have far less experience fending off left-handed opponents, and be less familiar with their angles of attack—whereas the left-hander will be accustomed from training to fight right-handers and exploit those weaknesses. This advantage is especially seen in fencing, with left-handers regularly taking the top spot and edging out right-handers. And this may not only be based on experience in fighting an opponent of an opposing hand—but also based on neuro-anatomy. Fine hand movements are controlled by the opposite eye. Thus, right-eye dominant left-handers are able to take in visual information and respond with greater speed (most of the population are left-eye dominant—thus, most right-handers).

Genetic studies have been carried out on “handedness.” The more left-handers there are in a population, the higher the chances are that the continuing generations will be left-handed. Based on the three biblical passages about left-handed Benjamites, there may have been a genetic propensity in this tribe for producing left-handers like Ehud. And as shown above, there was good reason to draft them into service.

A ‘Calf-Like’ King

The Bible is certainly not flattering in recounting the king of Moab’s physique. The name “Eglon” means “calf-like”—but perhaps “cow-like” might be more apropos. “[N]ow Eglon was a very fat man” (Judges 3:17; the Spanish rvr is a little more humorous to the English eye: Eglon was an “hombre muy grueso”). The sheer size of this king is demonstrated further down in the account.

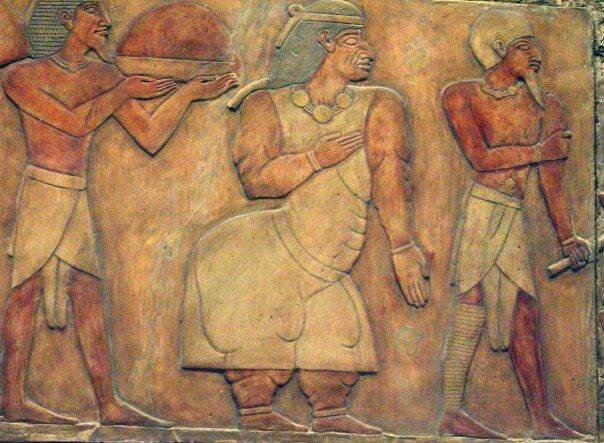

Most depictions of ancient kings portray relatively fit, muscular individuals—especially those from Egypt. But severely overweight rulers are not unknown in the ancient world. Perhaps the best portrayal from this time period is that of Queen Eti from the Land of Punt (a still unknown land—probably around the Horn of Africa). She is depicted on a 15th-century b.c.e. wall relief of Pharaoh Hatshepsut. (Quite a lot of study has been done to try to identify her confusing physical condition. There is no scholarly agreement—as such, it has been named “Queen of Punt Syndrome.”) Of course, it does not take much imagination to see how the privileged and opulent life of a sedentary royal such as Eglon could lead to his condition.

Ehud was chosen to deliver Israel’s tribute to Eglon at Jericho. But he would carry more than just tribute. “And Ehud made him a sword which had two edges, of a cubit length; and he girded it under his raiment upon his right thigh” (verse 16). We can get an idea of what this weapon may have looked like.

The “Uluburun shipwreck,” discovered southeast of modern-day Turkey, dates to this same period—the 14th century b.c.e. A large cargo was found aboard this sunken vessel, including some 150 Canaanite jars, Canaanite jewelry and a handful of Canaanite weapons. (“Canaanite” referring to the geographic region of the Holy Land, up into Syria). Right is a “Canaanite” sword and dagger from this trove that would have been about the same size as Ehud’s dagger—a cubit (around 50 centimeters, or 20 inches) in length.

Ehud’s company delivered the tribute and turned to go home. Ehud returned partway with them, before doubling back to the royal palace. “‘I have a secret errand unto thee, O king.’ And he said: ‘Keep silence.’ And all that stood by him went out from him” (verse 19). Verses 20-22 read in the New King James Version:

Then Ehud said, “I have a message from God for you.” So he arose from his seat. Then Ehud … took the dagger from his right thigh, and thrust it into his belly. Even the hilt went in after the blade, and the fat closed over the blade, for he did not draw the dagger out of his belly; and his entrails came out.

To the Quarries—and All-Out War

That a 50-centimeter dagger could be completely (and graphically!) swallowed up within Eglon’s fat, hilt and all, attests to the size of this individual. It would be interesting to try to get some kind of rough measure of his girth based upon this measurement.

Having killed the king, Ehud slipped out, locking the doors behind him. Eglon’s servants, who arrived later, feared to enter the locked room: “Surely he is covering his feet in the cabinet of the cool chamber” (Judges 3:24; a euphemism for using the toilet). Prof. Baruch Halpern has thoroughly researched the somewhat peculiar Hebrew text of Judges 3, and based on the account posits that Ehud’s dagger “exploded” Eglon’s anal sphincter (the odor giving the servants the impression that the king was on his lavatory). Further, Halpern believes that Ehud escaped from the king’s upper chamber by locking the doors from the inside, and lowering himself through the lavatory drain to a first floor janitorial access (see his analysis of the account here for more information).

After waiting a while, Eglon’s servants broke into the room and discovered the dead king. “And Ehud escaped while they lingered, having passed beyond the quarries, and escaped unto Seirah” (verse 26), a location in Mount Ephraim.

These “quarries” are also mentioned in verse 19, in relation to Gilgal—a location very close to Jericho. But “quarries” is not a good translation; this Hebrew word is translated in all other biblical passages as “graven images.” Other Bible translations render these as some form of “sculptured stones.” This may refer to some of the very paganism for which God had allowed Israel to be conquered by Moab. Alternatively, “gilgals” are known large “footprint”-shaped stone structures (of an Egyptian style), dating to the Israelite judges period. These peculiar structures have been found exclusively in the Jordan River Valley region. They are believed to be some kind of assembly point for ritual celebrations.

From this sculpted stone landmark Ehud continued on toward Mount Ephraim. There, he blew a trumpet and led an army of Israelites down from the mountain—which at that time was a densely wooded area. Verses 28-30:

And he said unto them: ‘Follow after me; for the Lord hath delivered your enemies the Moabites into your hand.’ And they went down after him, and took the fords of the Jordan against the Moabites, and suffered not a man to pass over. And they smote of Moab at that time about ten thousand men, every lusty man, and every man of valour; and there escaped not a man. So Moab was subdued that day under the hand of Israel. And the land had rest fourscore years.

And so Moab was vanquished by the Israelites. In fact, Moab is not described as fighting against the Israelites until the reign of Saul, some 300 years later (1 Samuel 14:47). And did the Egyptian military take advantage of Israel’s victory? Ramses ii’s battle against Moab took place not long after the Israelites defeated Eglon’s forces. Perhaps they piggy-backed off the success of the Israelite campaign, leading to a general collapse of Moabite influence.

The Bible does not say explicitly that Ehud became one of the judges over Israel, but it is clearly inferred in the following chapter. “And the children of Israel again did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord, when Ehud was dead” (Judges 4:1). And the sin-cycle began again—this time resulting in Canaanite oppression at the hands of Jabin and Sisera.

The Body of Evidence

Archaeology has not proved the existence of the protagonists themselves: the Benjamite Ehud and the Moabite King Eglon. But to be fair, only half a dozen Moabite kings have been identified by inscriptions across nearly 1,000 years of the kingdom’s existence.

The wider biblical account does, however, fit beautifully with discoveries from the historical period:

- Evidence for the 14th-to-13th-century b.c.e. existence of Israel and Moab;

- Evidence of long-standing territorial animosity between the two powers;

- A circa late-14th-century b.c.e. Jordanian tribal coalition, uniting against the inhabitants of the southern Levant (Israel);

- A palace-villa established atop the ruins of Jericho, briefly owned by a wealthy individual, with architecture and dating matching that of Eglon’s “summer parlour”;

- Stone landmarks that may match those referenced in Judges 3:19 and 26 in dating and location;

- And a collapsing Moabite power.

The period of the Israelite kings, from circa 1000 to 586 b.c.e., is well attested to in archaeology. But now we also have an emerging body of evidence for the nation of Israel’s earliest history in the Holy Land: the tumultuous, lesser-known—but fascinating and formative—period of the judges. A bloody period intended to highlight the pitfalls of relativism and following one’s own moral compass. As the book concludes and summarizes in Judges 21:25: “In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did that which was right in his own eyes.”

Articles in This Series:

Othniel v. Chushan-Rishathaim: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Ehud v. Eglon: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Shamgar v. the Philistines: Evidence for the Biblical Account