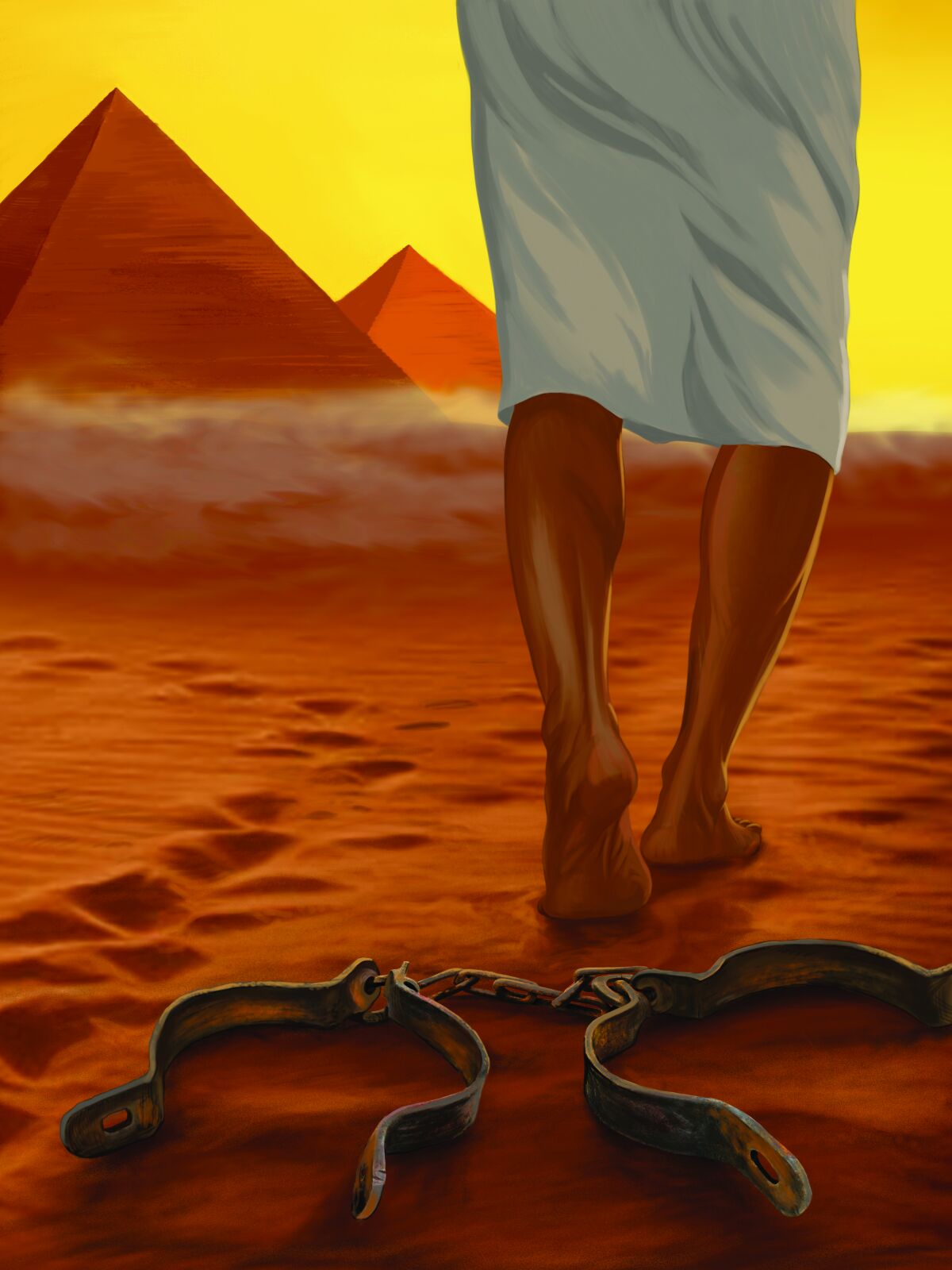

Evidence of the Exodus?

It’s that time of year. Across the world, Jewish families are sharing stories about Moses, the 10 plagues and Israel’s march through the Red Sea. The chief source of all these stories is the Bible, which gives a wonderfully detailed account of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt and the Exodus.

But how accurate is the biblical record? What does archaeology tell us about the Israelites in Egypt?

Archaeologists and scholars provide varying answers. “Really, it’s a myth,” says Dr. Zahi Hawass. Archaeologist Philippe Bohstrom looks at the evidence more favorably. For Haaretz, he wrote a piece titled “Were Hebrews Ever Slaves in Ancient Egypt? Yes.” Three days later, Haaretz posted another article by archaeology correspondent Ariel David titled “For You Were (Not) Slaves in Egypt.”

“The whole subject of the Exodus is embarrassing to archaeologists,” wrote Stephen Rosenberg in a 2014 Jerusalem Post article. “The Exodus is so fundamental to us and our Jewish sources that it is embarrassing that there is no evidence outside of the Bible to support it.” Apparently, archaeologists dislike questions about the Exodus because, Rosenberg says, “there is nothing in the Egyptian records to support it. Nothing on the slavery of the Israelites, nothing on the plagues that persuaded Pharaoh to let them go, nothing on the miraculous crossing of the Red Sea, nothing.”

Sounds like a closed case. But is it? Is there really “no evidence outside of the Bible” of the Israelites’ presence in Egypt?

Consider the Evidence

There is no denying that the search for evidence of the Exodus is a challenge. There are a few primary reasons for this.

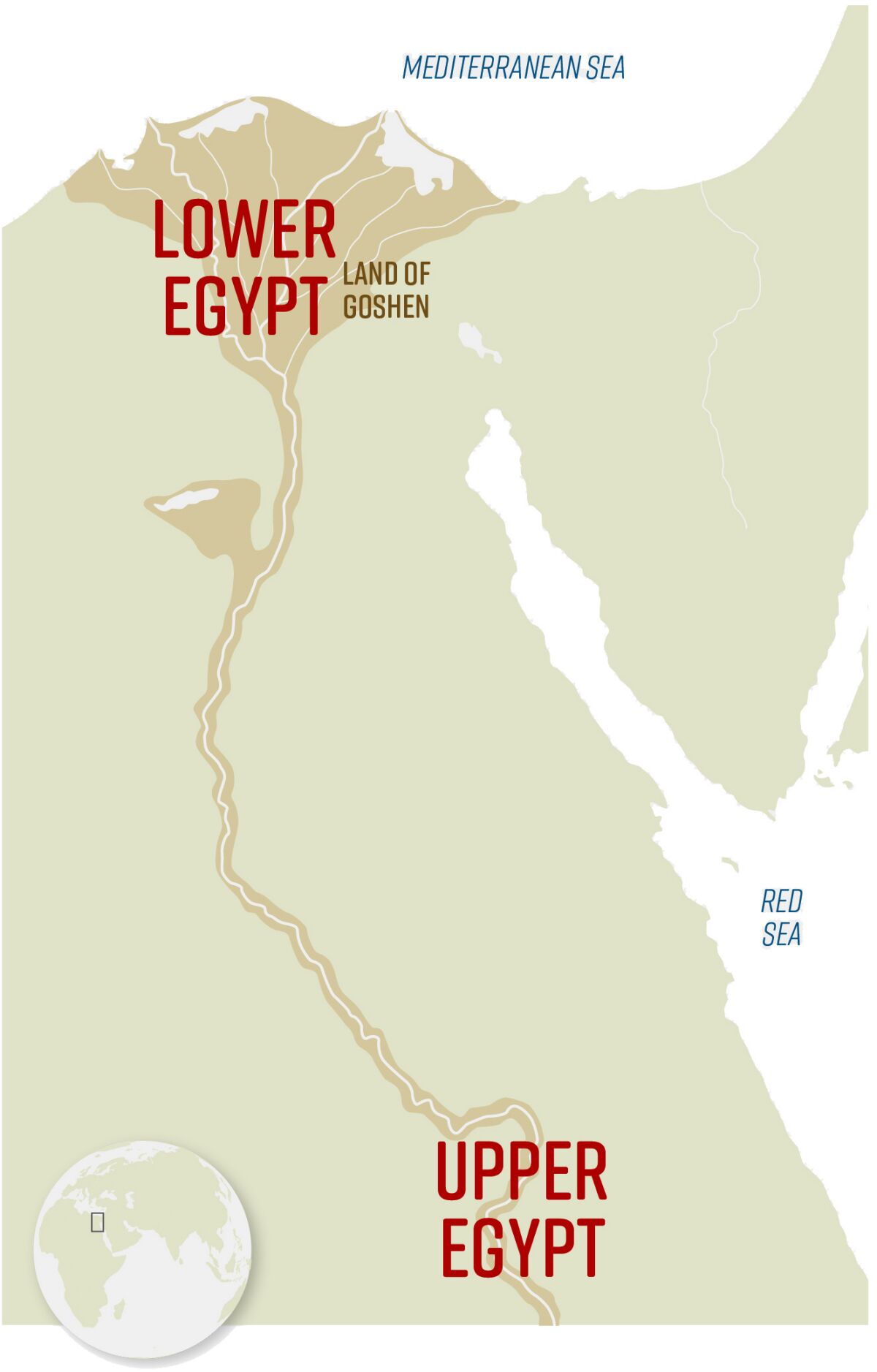

First, the Israelites during this period were initially slaves and then nomads. Both demographics are ghosts to the archaeological record. Second, Egyptian history was recorded by the pharaohs, who were notoriously biased. The pharaohs never admitted defeats and were known to erase and rewrite history, especially anything that reflected negatively on their legacy. Third, only a small slice of ancient Egypt has been excavated. Furthermore, the land of Goshen—the region of the ancient Israelites in Egypt—is in the Nile Delta, which floods regularly, causing the destruction of ancient buildings and documents.

Despite these challenges, however, there is evidence in support of the biblical record.

Readers will be familiar with the biblical account of Joseph being sold into Egyptian slavery, interpreting dreams, and eventually becoming second-in-command over Egypt. This history is recorded in Genesis chapters 39 through 45. Eventually, Joseph’s extended family (an entourage of at least 70, led by the patriarch Jacob) migrated from Canaan and settled in Egypt. They were welcomed by the pharaoh and became established as herdsmen in the fertile land of Goshen—a significant northern territory of the Nile Delta (Genesis 47:1-11). With Egypt’s food stores, they were able to survive the seven-year famine plaguing Egypt and the Levant at the time.

According to biblical chronology, this history, beginning with the migration of Jacob and his family, occurred around 1700 b.c.e. (see Exodus 12:40-41; Genesis 15:13; 12:1, 9-10; Galatians 3:16-17). What does Egyptian history record about this period?

Evidence of such migration is clearly documented on ancient Egyptian inscriptions (e.g. the Turin King List) and wall art, and demonstrated by archaeological excavations in the Nile Delta area. Evidence shows specific immigrations into Egypt from the land of Canaan up to and during the 1700s b.c.e. These Semitic immigrants settled in the area of the Nile Delta and coexisted alongside the native Egyptian 13th Dynasty, forming what is known as the 14th Dynasty. This period of coexistence is marked by a general decline in native Egyptian power, which scholars attribute to famine or plague (based on Middle Kingdom texts referencing famine-like events, and general instability).

Among other sources, the Turin King List and third-century b.c.e. Egyptian historian Manetho both document that around the start of the 17th century b.c.e. a “provincial ruling family” of these East Semitic migrants established a new and powerful independent dynasty over northern Egypt. Called the Hyksos, this new ruling class formed the 15th Dynasty of Egypt and ruled autonomously in this area for a century and a half.

During this period, Egypt was essentially split in two. Southern Egypt, known as “Upper Egypt,” was ruled from Thebes by the native Egyptian dynasty. Northern Egypt, known as “Lower Egypt,” was ruled by the Hyksos from the city of Avaris. Egyptian history shows that the Hyksos held the upper hand during this period, known as the Second Intermediate Period (circa 1700–1550 b.c.e.).

Avaris served as the capital for these “Semites,” also known as “West Asiatics” (a term referring to peoples of the Levant), of the 14th and 15th dynasties. This city was located within the Nile Delta (the modern site Tell el-Dab’a). The name of this city is interesting: It is close to the root word for “Hebrew,” avar, meaning to pass over, cross over, alienate—as a wanderer or nomad. In the 17th century b.c.e., Avaris became the “largest city in the world.” Archaeological excavations at this site have revealed housing styles similar to that of Canaan, along with Levantine-style weapons and pottery. They also found sacrificial remains notably excluding pig, leading excavators to speculate that some kind of “kosher” system was in place. Large food-storage silos were also discovered at the site.

The Jewish historian Josephus believed these Hyksos were the biblical Israelites. He interpreted the name Hyksos as being derived from the Egyptian phrase hekw shasu, meaning shepherd kings. Manetho also described the Hyksos as shepherds. Modern scholars have reinterpreted the etymology of “Hyksos” as “foreign rulers,” (translated from heqa-khase), yet the parallel with the biblical account—of Semitic immigration and large-scale establishment in Egypt’s Nile Delta—remains evident.

Reign of the Hyksos

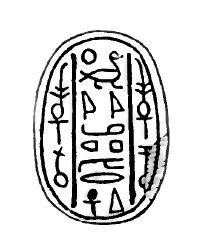

Among the early Semitic leaders recorded in Egyptian history, one is especially noteworthy. His name is Yacob-har (“Yacob” is equivalent to the anglicized “Jacob”). Twenty-seven scaraboid seals bearing the name of this still somewhat-obscure leader have been found throughout Egypt and in Canaan. The dating of these seals is still debated, but some evidence indicates that they date to the 17th century b.c.e. Could this have been the biblical patriarch Jacob, on the scene in both Egypt and Canaan at this time? The word “har” is a Hebrew-Semitic word for hill, mount or mountain. This word is connected with Jacob several times in the Bible (Genesis 31:25, 54; Isaiah 2:3). The name Yacob-har could thus mean something akin to “Jacob’s mount.”

The Bible says Jacob was a highly respected leader in Egypt, as well as in Canaan. When he died, he underwent a 40-day embalming process and was mourned by the Egyptians for 70 days (Genesis 50:1-3; this 70-day mummification-to-burial process, including 40 days of packing and preserving the internal organs and body, was well known in ancient Egypt).

A doorjamb inscription discovered by archaeologists in ancient Avaris reveals the name of another such Semitic ruler: Sakir-har. “Sakir” means reward. This name has a close parallel to one of Jacob’s sons, Issachar (or “Ish-Sakir”), meaning “there is a reward.”

There was a time when historians believed the Hyksos swept into Egypt as violent Semitic invaders during the Second Intermediate Period. This view was based on ancient Egyptian “propaganda” sources and has since changed. Today, many scholars believe the Hyksos steadily settled over an ever expanding territory, gradually growing in power. “If you study ‘fake news’ from ancient Egypt, you would consider the Hyksos a band of nasty, marauding outsiders who invaded and then brutally ruled the Nile Delta until heroic kings expelled them,” wrote Egyptologist Danielle Candelora in an article for the American Research Center in Egypt. “In fact, the Hyksos had a more diplomatic impact, contributing to progress in culture ….”

Candelora’s article explores the major social, economic and cultural impact of the Hyksos on Egypt. “Tell el-Dab’a [Avaris] was a culturally blended community featuring intermarriage and peaceful coexistence,” she wrote. “Several West Asian individuals were even officials for [native Egyptian] kings, overseeing trade in the Near East and lucrative mining expeditions to the Sinai Peninsula. Rather than an ‘invasion,’ it appears that as the centralized authority of Egyptian kings declined, elites at Tell el-Dab’a increased their local power until, by a coup or simply a slow, peaceful process, they took the Heka Khasut [Hyksos] title and became kings in their own right.”

Were these Hyksos identical with the Hebrews? The fact that they initially dominated the greater territory of Egypt fits with the biblical account: “And the children of Israel were fruitful, and increased abundantly, and multiplied, and waxed exceeding mighty; and the land was filled with them” (Exodus 1:7).

It is possible that the ruling Hyksos 15th Dynasty included people of different Semitic backgrounds, not exclusively Hebrew—but that they governed over a significant Israelite population perhaps established by the initial 14th Dynasty rulers from Canaan. Whatever the case, the Bible does describe that at the time of the Exodus, a “mixed multitude” left Egypt with the Israelites (Exodus 12:38). The wider picture of large-scale Semitic dominance in Second Intermediate Egypt fits perfectly with the biblical account.

Overthrow of the Hyksos

Kamose was the last of the Theban pharaohs, reigning at the very end of the Second Intermediate Period (mid-16th century b.c.e.). Kamose attempted to persuade his fellow Theban counselors to back him in “saving Egypt” from the stain of having foreign rulers over Lower Egypt, and in reclaiming the Nile Delta as Egyptian territory.

Revealingly, Kamose’s advisers argued that the status quo with the Hyksos was favorable and should be preserved. This history was recorded on Kamose’s Carnarvon Tablet, discovered in 1908 in a mortuary complex near Luxor, on the west bank of the Nile: “Then spake the magistrates of his council: … We are doing all right with our [part of] Egypt …. Their free land is cultivated for us, and our cattle graze in the Delta fens, while corn is sent for our pigs. Our cattle have not been seized and have not been tasted …. Only when one comes who [acts against us] should we act against him.”

Pharaoh Kamose was not convinced. His quest to unite Egypt is similar to what the Bible records about an unnamed biblical “king” of Egypt who arose and “knew not Joseph. And he said unto his people, ‘Behold, the people of the children of Israel are too many and too mighty for us; come, let us deal wisely with them …” (Exodus 1:8-10).

Egyptian history shows that Kamose’s quest to reunite Upper and Lower Egypt was carried out with partial success. Significant territorial gains were made in subjugating the Hyksos. But it was his successor, Ahmose i, who finally overthrew the Hyksos dynasty circa 1550, uniting all of Egypt under his rule and beginning the opulent New Kingdom period.

Manetho recorded that, following their defeat, some 240,000 Hyksos were driven out of the land into Sinai; they were chased all the way into the Levant, where they “built a city in that country which is now called Judea … and called it Jerusalem.”

Was this event the biblical Exodus? Josephus believed it was. But a 1550 defeat and routing is about a century too early for the biblical Exodus. Moreover, archaeological evidence does not attest to such a defeat and destruction. According to Candelora, “[N]o solid evidence supports such destruction [in 1550].” So, what exactly happened?

Candelora continued: “Instead, archaeological material at Tell el-Dab’a indicates a West Asian population continued to live there into the New Kingdom, raising questions about how many people were actually expelled.” She cites later Egyptian writings that mock the Hyksos, proving that at least some Hyksos remained in Egypt.

Perhaps a better explanation, then, is that the northern Semites of Egypt simply lost their ruling autonomy in the mid-16th century—and logic would dictate that the new ruler, Ahmose i, would requisition them as slaves in starting what is now called a “golden age” of Egyptian empire—the New Kingdom. As Biblical Archaeology Society contributor Noah Wiener wrote, “The expulsion of the Hyksos may not have been a single event …. After the Hyksos were defeated by Ahmose, some Hyksos people likely remained in Egypt, perhaps as a subjugated class. The Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut (1489–1469 b.c.e.) recorded the banishment of a group of Asiatics from Avaris, the former Hyksos capital” (March 2013). Such subjugation would be consistent with the first chapter of Exodus, which records the mass population put into slavery.

But what about Manetho’s exodus? Can that be explained? In fact, Manetho does record a later “exodus”—in connections with the Exodus—one that appears to fit even more closely with the biblical account (more on this further down). The actual expulsion of the Hyksos may better relate to this later event.

The book of Exodus describes how the enslaved Israelites undertook vast construction work for the new Egyptian ruler. This fits with the archaeological record, which shows that after consolidating control over all Egypt, Pharaoh Ahmose initiated massive nationwide construction projects designed to reinvigorate Egyptian nationalism. At Avaris, he had a new palace constructed—the same location that would later be incorporated into an even larger city known as Pi-Ramesses (Exodus 1:11). These monumental construction efforts were continued by a series of succeeding pharaohs.

Egyptian Slavery

The biblical record describes the harsh physical conditions the Israelites endured as slaves in Egypt. Many details of their slavery have parallels in archaeological discoveries.

First, slavery in Egypt during the middle-second millennium b.c.e. is well attested. The Bible records that one of the primary tasks of the Israelites was making bricks. A famous wall painting in the tomb of the 15th-century b.c.e. vizier Rekhmire, discovered in the early 1800s, shows a force of Semitic slaves, young and old, making bricks. The inscription accompanying this wall painting reads: “[T]he very numerous […] building with ready fingers, skilled in his duty, causing vigilance among the [conquered] who hear the sayings of this official …. The taskmaster, he says to the builders: ‘The rod is in my hand; be not idle.’ … Laying the brick, in order to build the storehouse anew …. Let your hands build, ye people. Let us do the pleasure of this official in restoring the monuments of his lord ….”

Compare this Egyptian inscription with the biblical record. The book of Exodus reads: “[A]nd they built for Pharaoh store-cities …. So they made the people of Israel serve with rigor, and made their lives bitter with hard service, in mortar and brick …. And the foremen of the people of Israel, whom Pharaoh’s taskmasters had set over them, were beaten …. [H]e said, ‘You are idle, you are idle …’” (Exodus 1:11, 13-14; 5:14, 17; Revised Standard Version).

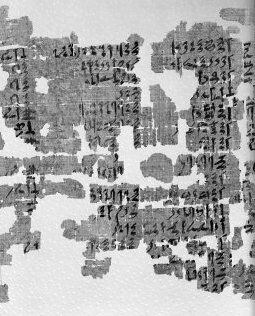

Exodus 1:15 records the name of a Hebrew slave-midwife, Shiphrah. This Semitic name was found on an ancient slave list (now called the Brooklyn Papyrus), discovered on the antiquities market around 1890. Although it is unlikely that these are the same individuals (the Brooklyn Shiphrah appears to predate the biblical Shiphrah by about 150 years), it does attest to the presence of this Semitic name among slaves in ancient Egypt.

Another interesting detail corroborated by an ancient record is found in Numbers 11:5, which states that the Israelite slaves were fed leeks and onions. Fifth-century b.c.e. historian Herodotus wrote of viewing an ancient pyramid inscription on his tours of Egypt that detailed a menu of leeks and onions for the workmen.

A Leader ‘Born of Water’

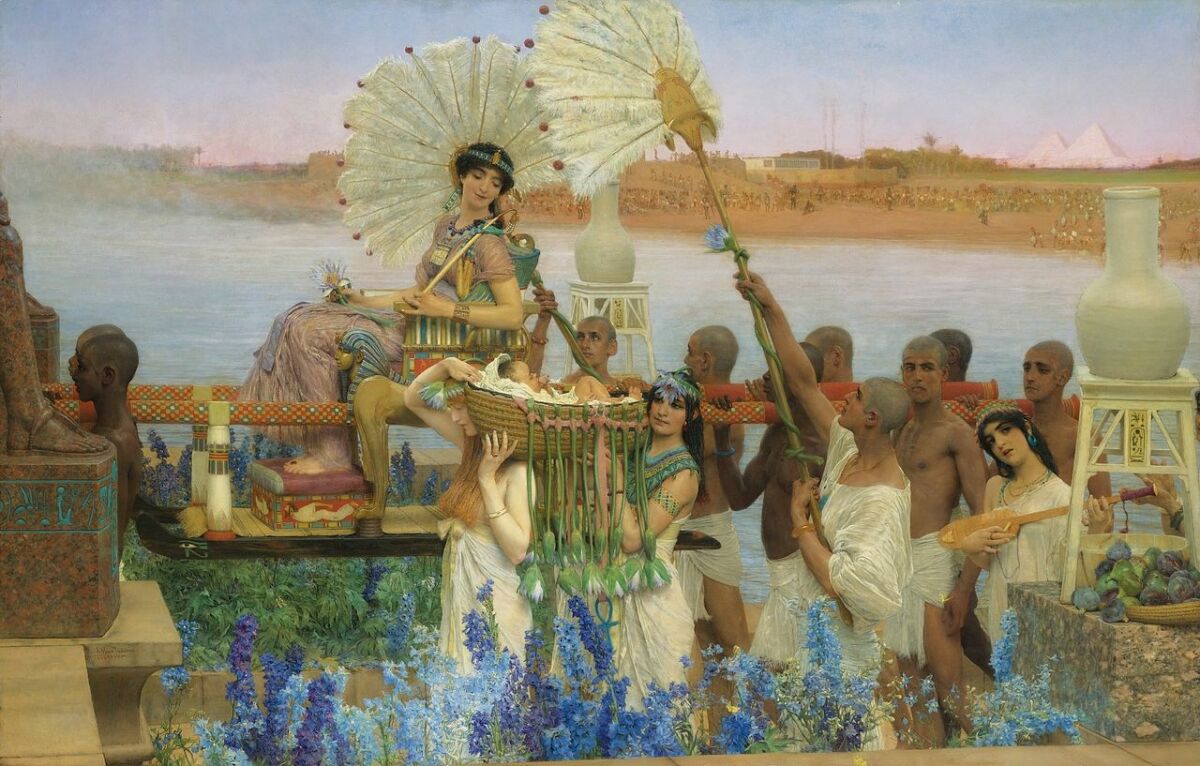

Moses is one of the most famous figures in the Bible. As an infant, he was set adrift on the Nile to escape being killed by the Egyptians. Rescued by a royal princess, Moses was raised within the Egyptian courts. He eventually realized the plight of his people and was used by God to deliver the Israelites out of Egypt.

According to traditional chronology, Moses would have been born in the late 16th century b.c.e. Exodus 2:10 records that the name “Moses” (“Moshe” in Hebrew) was given to the infant by the Egyptian princess because, as she said, “I drew him out of the water.” The names Moses, Mosis, Moshe, Mose are interchangeable. This is a word of Egyptian origin, meaning to be “drawn” or “born”; in Moses’s case, born of water. This Egyptian name element is common, especially during the relevant 16th to 15th centuries b.c.e., fitting alongside contemporary Egyptian royalty such as Tuthmose, or Tuthmosis, “born of Tuth”; Ahmose; Amenmose; Ramose; Kamose; Wadjmose; etc. It is also known as a standalone name.

Osarseph and the Exodus

Manetho’s later “exodus” account is that of Osarseph. According to Manetho, Osarseph was an ancient Egyptian priest who turned renegade against the Egyptian Pharaoh Amenophis (the Greek form of Amenhotep). Osarseph came to lead an army of 80,000 slaves—characterized by Manetho as “lepers,” who were established at Avaris—telling them to forsake the Egyptian gods.

Manetho related that Osarseph drove Amenophis into Ethiopian exile. Finally, Amenophis returned, rising up to overthrow Osarseph, his followers and his Hyksos allies. Pharaoh Amenophis chased them east out of Egypt “and pursued them as far as the bounds of Syria.” Josephus quoted Manetho as saying, “Osarseph changed his name and called himself Moses.”

Some scholars believe this story is fictional, that it is some kind of remembrance of trauma during the 16th-century Hyksos period or the 14th-century Amarna period. Manetho was known for exaggerating accounts and genealogies—and a pro-Egyptian, anti-Semitic bias is evident: “Lepers” is understood to mean a denigration of foreign slaves, rather than a literal physical condition. But no evidence exists that this account is fictional and should be dismissed wholesale. What if it really was a memory of an actual event that occurred during the mid-15th century b.c.e.?

Several elements in Manetho’s much-dramatized story fit with the biblical account of the Exodus. Even an Ethiopian element loosely connects: Jewish historians Josephus and Atrapanus (second century b.c.e.) record a young Moses as a successful Egyptian military commander in Ethiopia (see also Numbers 12:1; King James Version). And identifying an Amenhotep as Moses’s opponent makes a great deal of sense—because, as archaeology reveals, Amenhotep ii is a close fit for the pharaoh of the Exodus.

Evidence of the Exodus?

There is no denying that the search for evidence of the Israelites in Egypt is obscure and that some specific details are vague. Was Amenhotep ii the pharaoh of the Exodus? Probably. Was Hatshepsut the biblical “Egyptian princess”? Possibly. Was Osarseph Moses? Maybe. Did the Ipuwer Papyrus—containing a detailed account of plagues and utter devastation befalling Egypt (see pages 10-11)—refer to the same events as the biblical 10 plagues? Likely.

But against this backdrop of maybes and probablys—parallel stories and similar accounts that lend strong evidence but not yet absolute proof—we do have the wider picture proved. We have a clear, parallel Semitic immigration into northern Egypt, “Goshen,” from the land of Canaan at just the right time frame. We witness a powerful historical rise of Semitic people in the land, expanding so far and wide as to back the native Egyptian dynasty into the smaller south of the country. We witness the rise of a native nationalistic pharaoh, who retook the northern lands and enacted a monumental construction campaign built on the backs of slaves, including at the site of Avaris/Pi-Ramesses. And we have some form of exodus of a great multitude of Semites from Egypt into the Sinai, roughly around the middle part of the second millennium b.c.e.

And by the 14th century b.c.e., what do we witness in the land of Canaan? Mass invasion and conquest of Canaanite territory by a strange nomadic people known as the “Habiru,” as attested by dozens of clay tablets sent from Canaanite leaders to the Egyptian pharaoh, pleading for his help. But that is another story for another day.

Is there really “no evidence” of the Exodus? Hardly. Despite the best efforts of propaganda-driven pharaohs and modern, agenda-driven scholars, a solid frame of Egyptian evidence for this remarkable biblical story does come into focus.

Over the course of thousands of years, multiple millions of Jews have observed the Passover, commemorating their freedom from Egypt. Theirs’ is an observance of faith—but not only that: It is an observance of history.

Sidebar: Dating the Exodus

There are two primary schools of thought on the date of the Exodus. One believes the Exodus occurred in the 15th century b.c.e.; the other believes it occurred in the 13th century b.c.e.

The first view is based on biblical chronology. The Bible records many genealogies and events, some of which can be aligned with secular events recorded in historical documents. Putting together the Bible and ancient secular history, it is possible to fix a reasonably solid date for the construction of Solomon’s temple: circa 967 b.c.e. 1 Kings 6:1 states that the temple began to be built in the 480th year after Israel left Egypt, thus putting the Exodus around 1446 b.c.e. This date matches other scriptures, such as Jephthah’s speech about how long the Israelites were in the land during the period of the judges (Judges 11:26).

The belief that the Exodus occurred in the 13th century b.c.e. is based on the interpretation of select archaeological evidence. A number of sites across Israel have destruction layers dating to the 13th century. Some archaeologists believe these destruction layers represent the Israelite conquest of the Promised Land following their departure from Egypt. Further, Exodus 1:11 says the Israelites built a city in Egypt named Ramses. Pharaoh Ramses ii (popularly considered the pharaoh of the Exodus) reigned during the 13th century and built the city Pi-Ramesses.

However, there are other explanations for both the 13th-century destruction layers and the city of “Ramses.” The 13th-century destruction layers in Canaan fit easily within the brutal biblical judges period. Additionally, pinning the Exodus to the 13th century overlooks 15th-to-14th-century destruction layers discovered at specific post-Exodus sites whose destruction is mentioned in the Bible.

As for the city “Ramses,” the Bible actually mentions this location during the days of the patriarch Jacob, many centuries before its construction (Genesis 47:11). It is, then, clearly used as an anachronistic name for an earlier site.