The Egyptian Empire Strikes Back: Evidence of Shishak’s Invasion of Judah

In a number of cases, archaeology has unveiled and corroborated entire biblical stories. One example is the Babylonian invasion of Judah: Excavations have revealed citywide, fiery destruction in Jerusalem dating to the early sixth century b.c.e.; bullae belonging to the biblical princes Jehucal and Gedaliah, enemies of the Prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 38:1); a tablet documenting the rations given to the captive King Jehoiachin (2 Kings 25:27-30); and another tablet documenting Nebuchadnezzar’s installment of the final king, Zedekiah (2 Kings 24:17).

Another example from more than a century earlier is Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah at the end of the eighth century b.c.e. Region-wide Assyrian destruction has been found all across ancient sites in Judah—notably at Judah’s “second city,” Lachish (2 Kings 18:14)—but most notably not at the capital, Jerusalem (2 Kings 19:32-36). Archaeological discoveries have corroborated the names of key individuals in the account: Sennacherib, Hezekiah, Isaiah, Eliakim, Hilkiah and Shebna (as recorded on Sennacherib’s inscriptions, as well as on a number of bullae and other inscriptions). Other key elements in the story have also been confirmed, such as Hezekiah’s payment of 30 talents of gold (2 Kings 18:13; recorded on Sennacherib’s Winged Bull Inscription) and his precautionary construction of a new water system (2 Kings 20:20; the Siloam Tunnel).

There is yet another such example, albeit comparatively less well-known, from more than two centuries earlier; this one featuring the earliest directly named pharaoh in the biblical account. It’s a violent epoch for which archaeology has remarkably corroborated the biblical account, but it is also one with a remaining degree of mystery and intrigue. It’s an event that even survives in popular culture today, serving as the plot premise to the popular Indiana Jones film Raiders of the Lost Ark.

In this article, we’ll review the evidence for Pharaoh Shishak’s invasion of Israel and Judah in the late 10th century b.c.e.

Setting the Scene

“… Thus saith the Lord: Ye have forsaken Me, therefore have I also left you in the hand of Shishak” (2 Chronicles 12:5). These were the terrifying words the Prophet Shemaiah issued to King Rehoboam during the early part of his reign.

Rehoboam, the son and successor of King Solomon, had a 17-year reign that is generally dated to circa 931–914 b.c.e. He is accounted in the Bible as a rebellious, rash and reactionary ruler; during his reign, the united kingdom of Israel fell apart almost immediately. Following Rehoboam’s refusal to lower taxes, the northern 10 tribes united around Solomon’s former superintendent Jeroboam, with Rehoboam narrowly avoiding assassination (1 Kings 12:14-20).

On the throne of Egypt at this time was a pharaoh by the name of Shoshenq i (also rendered as Sheshonq/Shashank/Sheshonk). Shoshenq, who ruled circa 945–924 b.c.e., was a Libyan, not a native Egyptian, thus his dynasty is sometimes referred to as the “Libyan Dynasty.” This was during Egypt’s centuries-long Third Intermediate Period, a time of overall fragmentation and division in which Egypt was variously ruled by non-native pharaohs (i.e. Libyans and Kushites and, in some cases, a number of pharaohs at a time).

The name and dating for Shoshenq i is a remarkable fit with our biblical Pharaoh Shishak. (The slight spelling difference in the names is actually less obvious when comparing the Egyptian with the Hebrew; see sidebar below, “‘Shoshenq’ as Shishak”). For these reasons, scholars are nearly unanimous—both minimalists and maximalists alike—in identifying these individuals as one and the same. (There is a caveat to this; see “Was Ramesses II Shishak?”)

Egyptologist Prof. Kenneth Kitchen notes that “the dates of Shoshenq i (ca. 945–924) fit the dates for Rehoboam (ca. 931–914).” But that’s not all: The chronology matches up even more tightly in relation to his invasion occurring in Rehoboam’s “fifth year” (2 Chronicles 12:2). “Even more closely, Shoshenq i’s unfinished works in celebration of his victory date to his Year 21 onward (Silsila stela, that year; ca. 925), setting his campaign in Years 19 or 20 (927f. or 926f.), while the fifth year of Rehoboam is about 926/925 also. The Egyptian and Hebrew dates series are independent of each other, but match very well” (On the Reliability of the Old Testament; emphasis added throughout).

This Egyptian ruler is mentioned by name seven times in the biblical account, primarily in relation to Rehoboam. But interactions with this king are not the earliest mention of this pharaoh: He is actually first introduced in the context of Solomon’s kingdom.

“Solomon sought therefore to kill Jeroboam; but Jeroboam arose, and fled into Egypt, unto Shishak king of Egypt, and was in Egypt until the death of Solomon” (1 Kings 11:40). 1 Kings 11 describes Solomon’s collapse into idolatry, womanizing and excess. As a result, God “raised up adversaries” to trouble him—one of whom was Jeroboam, an individual Ahijah the prophet declared would wrest control of the northern tribes from Solomon’s dynasty (verse 31).

Chronologically speaking, Jeroboam’s fleeing to Shishak in Egypt also serves as additional corroboration for the identity of the biblical Shishak as Shoshenq i, whose first 14 years on the throne overlapped with the last 14 years of Solomon’s reign.

Another such “adversary” who initially sought refuge in Egypt was Hadad of Edom (verse 17). Why was such safe haven and favor afforded these enemies of Solomon by the ruler of Egypt? The logical answer is that Solomon’s broad and expansive kingdom exerted full control over the crucial regional trade routes running between Egyptian, Hittite and Mesopotamian lands. These routes included the coastal Via Maris and overland Via Regis, the passages across both of which were evidently taxed by Solomon (e.g. 1 Kings 10:29; Ezra 4:20). The rulers of Egypt during the reigns of David and Solomon (except probably Pharaoh Siamun, father-in-law of Solomon) would have been biding their time, only too happy to support “enemies” who would ultimately weaken and fracture the Israelite kingdom, making it easy pickings for a time of eventual Egyptian resurgence.

That time came during the early years of the reign of King Rehoboam.

Pharaoh’s Onslaught

Shoshenq i rose to power as a military leader during the final years of Egypt’s 21st Dynasty, eventually taking the throne and establishing a new dynasty of his own—the 22nd Dynasty. This dynasty would continue for well over 200 years (943–716 b.c.e.), becoming one of the longest-lasting dynasties in Egyptian history. Four other pharaohs in the dynasty would go on to bear his regnal name. But it was not until right at the end of his reign that he invaded the Levant.

“And it came to pass in the fifth year of king Rehoboam [circa 926–925 b.c.e.] that Shishak king of Egypt came up against Jerusalem, because they had dealt treacherously with the Lord, with twelve hundred chariots, and threescore thousand horsemen; and the people were without number that came with him out of Egypt; the Lubim, the Sukkiim, and the Ethiopians. And he took the fortified cities which pertained to Judah, and came unto Jerusalem” (2 Chronicles 12:2-4). That Shoshenq’s forces included Libyans (“Lubim”) would not be unusual, given the pharaoh was a Libyan himself. More interesting is the biblical reference to “Sukkiyim, or scouts, Libyan auxiliaries known in Egyptian texts from the 13th/12th centuries onward, an intimate detail that we owe exclusively to the chronicler and his (nonbiblical) sources,” writes Kitchen (ibid).

A remarkable Egyptian account of this invasion exists today.

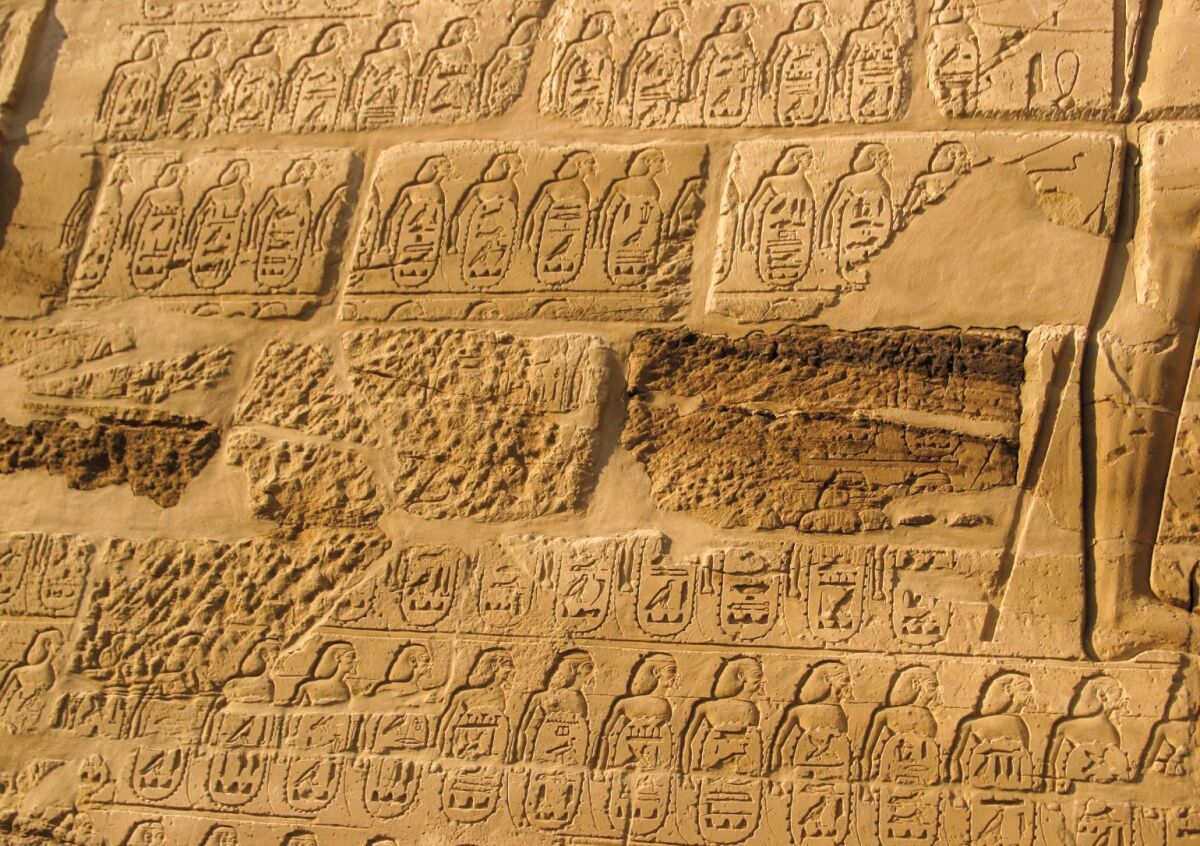

Deep in the south of Egypt at the vast and impressive Karnak Temple in Luxor is a 6-meter-high (20-foot) temple gate known as the “Bubastite Portal” (named after the Delta city of Bubastis). The right-hand side of the gate’s main facade is adorned with inscriptions commemorating Shoshenq’s invasion into the Levant. Decorating the top are images of Shoshenq’s opponents being trampled upon by horses and chariots (befitting the description in 1 Chronicles 12).

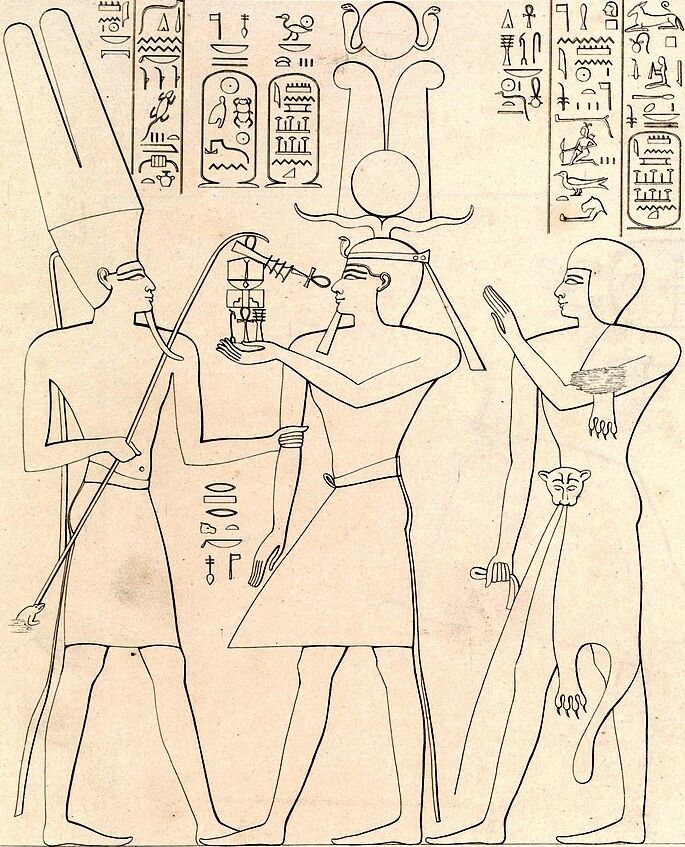

On the right of this particular relief is a colossal image of Shoshenq i smiting his enemies (or was—this image of the pharaoh himself is virtually invisible today). To his left is a smaller (yet still large and prominent) image of the god Amun, leading by rope multiple ordered rows of individuals to be smashed by the smiting pharaoh. In front of each of these individuals is an oval shape known as a “cartouche,” or name ring, bearing a hieroglyphic inscription. These represent the individual names of the towns and cities captured by Shoshenq i.

Many of the cartouches have been weathered and damaged beyond legibility; still, a majority can be read, revealing many familiar locations from the biblical account, such as Aijalon, Gibeon, Megiddo, Socoh and Arad. One of the most intriguing place-names references “the Field of Abram” (which is broadly identified as the earliest extrabiblical reference to the name of the patriarch). These neatly ordered rows of cartouche names reveal that Shoshenq i’s path of conquest took him nearly as far as the Sea of Galilee in the north and down into the Negev desert in the south (see map below).

Many scholars regard this vast set of cartouches (originally 156) as a sort of “itinerary”—a road map of Shoshenq i’s invasion. The layout of the cartouches is divided into various main parts: an initial row, naming the “Nine Bows,” or traditional enemies of Egypt; followed by an upper register of five rows containing place-names of cities and towns in central and northern Judah and Israel; below, another register of five rows containing place-names in the south of Judah and Edomite territory (the Negev desert regions); and finally, a completely separated group of some 30 cartouches on the bottom right of the Bubastite Portal, very few of which are legible.

In simplest summary, it appears that Shoshenq i’s vast army split into two parts when it arrived in Judah—one part carving a path toward the north, and one part toward the south (likely with aims toward controlling the southern copper mining industry and trade routes in this area).

Over the decades, scholars have attempted to make sense of the order of the individual cartouches on the Bubastite Portal, believing them to be in some kind of logical, progressive arrangement. “The problem is that there seem to be significant gaps,” wrote Prof. Yigal Levin in his article “Did Pharaoh Sheshonq Attack Jerusalem?” “[T]hey don’t connect into a reasonable itinerary.

In 1957, Israeli scholar Benjamin Mazar published what he considered to be a solution to this problem: the upper register was written in boustrophedon style [‘as the ox plows’—reading across in one direction, then down, and across in the other direction] …. Mazar’s proposal was accepted enthusiastically by some scholars, but rejected out of hand by others. The main problem is that while boustrophedon writing was fairly common in archaic Greek texts and in Luwian hieroglyphic writings, it is almost unheard of in Egyptian hieroglyphic texts. Moreover, the convention in Egyptian is that the ‘figures’ above each name-ring are drawn facing the beginning of the line, and in the Sheshonq inscription all of the figures in all of the rows are facing to the right.

“So the bottom line is, we just don’t have enough data to reconstruct Sheshonq’s exact itinerary,” Levin concludes (Biblical Archaeology Review, July-August 2012). Debate about the exact itinerary aside, however, we do have an impressive array of places that Shoshenq i did conquer.

Sites Destroyed—and Not Destroyed?

Excavations at a number of these sites have revealed fiery destructions dating to this very period. A case in point is a particularly large destruction event that took place at the major city of Megiddo. Alongside the destroyed stratum, a victory stele fragment was found at the site in 1925, during the excavations led by German archaeologist Gottlieb Schumacher. The fragment bore the name of Shoshenq i, clearly part of a triumphant victory stone set up at the site to commemorate his victory there.

An interesting sidenote to this Megiddo stele discovery is that many early scholars had wondered if Shoshenq i really did undertake this campaign into the Levant, or if his Bubastite Portal inscription just copied these names from elsewhere, attributing to himself an ultimately made-up campaign. This was a theory promoted by the infamous German orientalist Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918), one of the key originators of the Documentary Hypothesis (a popular minimalist theory for the very late formulation/fictionalization of the Hebrew Bible).

The discovery of Shoshenq’s stele at Megiddo, matching the Megiddo cartouche on the Bubastite Portal, ultimately was sufficient to put down such theories of a “faked” campaign. The late biblical geographer Prof. Anson Rainey wrote: “This inscription can only be based on intelligence information gathered during a real campaign by Pharaoh Shoshenq” (The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World).

We have, then, sites bearing destruction layers dating to Shoshenq’s invasion. Yet for many of the sites mentioned on the Bubastite Portal, we do not have destruction layers—including at such important sites as Arad and Beersheba in the Judean south, and Rehov in the north. How can this be explained?

The explanation was already given some 2,000 years ago by the first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus: “But God sent Shishak, king of Egypt, to punish them for their unjust behavior towards Him …. Now therefore when he fell upon the country of the Hebrews, he took the strongest cities of Rehoboam’s kingdom without fighting; and when he had put garrisons in them, he came last of all to Jerusalem” (Antiquities of the Jews, 8.10.2). A significant number of these cities had simply surrendered before the might of Shoshenq i’s forces.

But now, in the words of Josephus, we come “last of all to Jerusalem”—the biggest mystery of them all.

What About Jerusalem?

“Then the princes of Israel and the king humbled themselves; and they said: ‘The Lord is righteous.’ And when the Lord saw that they humbled themselves, the word of the Lord came to Shemaiah, saying: ‘They have humbled themselves; I will not destroy them; but I will grant them some deliverance, and My wrath shall not be poured out upon Jerusalem by the hand of Shishak. Nevertheless they shall be his servants; that they may know My service, and the service of the kingdoms of the countries’” (2 Chronicles 12:6-8).

And just as with the sparing of Jerusalem during Sennacherib’s eighth-century b.c.e. invasion of Judah, there is likewise no late 10th-century, Shoshenq i period destruction found in Jerusalem.

But there is also no mention of Jerusalem on the Bubastite Portal. How could this be? After all, Jerusalem is the one key city mentioned in the biblical account of Shishak’s invasion.

This has been a major point of debate for the past two centuries. The very first individual to translate the cartouches on the Bubastite Portal—the very individual credited with deciphering hieroglyphic script in the first place, Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832)—believed he had indeed found the reference to Jerusalem. One of the cartouches read ydhmlk—thus interpreted by him as ydh mlk, “Kingdom of the Jews.”

This would be a rather odd rendition of the word, however; in the century since, this cartouche was reinterpreted as instead reading yd hmlk, referring to a northern place-name, Yad Hamelekh.

Another cartouche translated by Kitchen reads “Heights of David.” Could this perhaps refer to Jerusalem, the City of David, perched atop the Judean highlands? Unlikely. Kitchen himself does not believe this to be so; this cartouche is grouped together with those of the Negev regions (a location, ironically, in which David sought refuge from Saul—befitting the regional name). Furthermore, the proper name of Jerusalem is known in earlier Egyptian texts and correspondence, so there would have been no reason to refer to it by a different name.

So why is there no mention of this key capital city on Shoshenq’s wall relief?

A relatively common answer is that Jerusalem was not destroyed by the pharaoh, so it was not recorded on the list. But this seems unlikely: As noted, other cities were also not destroyed yet are attested to on the portal.

Probably the best answer is the simplest: A full third of the names on this list are illegible. It is more than likely that the name of Jerusalem was contained in a now-unreadable part of the inscription. (This is also the likely explanation for the Judahite city Libnah, which does have a significant destruction layer attributed to Shoshenq’s invasion, but is also not found among the preserved list of names on the Bubastite portal.)

Some, such as Egyptologist David Rohl (see “Was Ramesses II Shishak?”), have argued that the cartouches referencing cities in the geographic region of Jerusalem are readable, and there is no mention of the capital in this part of the inscription—thus there is a tension with the biblical text. Yet despite attempts to map the pharaoh’s city-to-city itinerary, there are issues in reconstructing a layout, and notably there is no real knowledge about the route Shoshenq took in returning to Egypt—for as Josephus indicated, it is on this return journey that Shishak finally stopped at Jerusalem to plunder the city. This would certainly be logical in order to transport the wealth back into Egypt, rather than carry it with them, along their campaign up into northern Israel.

Points of Contention

There are other points of contention sometimes raised about Shoshenq’s invasion. One is why such a large amount of site names from the northern kingdom of Israel are included on the Bubastite Portal. Doesn’t the Bible emphasize this as an invasion event in relation to Judah? This is readily answered by the biblical account at this point in time being focused primarily on Jerusalem and Judah (especially in the case of the chronicler, who relays the most detail about Shishak). It is an example of how the biblical authors often present a Jerusalem-based perspective of events.

2 Chronicles 12:4 does indeed state that Shishak “took the fortified cities which pertained to Judah.” But the Bible does not say that it was only Judah that was afflicted by this invasion. Intriguingly, it also relays the distress and repentance of “the princes of Israel” (verse 6)—implying that the northern kingdom of Israel was under duress at this time as well. (Furthermore, the emphasis on these princes of Israel, rather than King Jeroboam, could imply a still-fractured conglomerate of tribes in the north, not yet fully organized behind the new breakaway king.)

But what about Jeroboam or Rehoboam? Judah or Israel? Couldn’t Egypt’s artificers have taken time to inscribe any of these names on the Bubastite Portal?

Professor Kitchen isn’t bothered by such questions: “So this great list does not mention either a Rehoboam or a Jeroboam, or the ‘state names’ of Judah or Israel; that was never done in such long town lists. …

[E]xactly like all his New Kingdom predecessors, Shoshenq i did not deign to name his adversaries, and long, detailed topographical lists like his and theirs almost never name states, just series of settlements. So no mention of the names Judah, Israel, Rehoboam, Jeroboam was ever to be expected in his normal-type list that we do possess ….

What we do have is several series of names of places known in both Judah and Israel, from which Shoshenq’s course of campaign can be discerned. This is valuable, in that it shows that Shoshenq i chose not only to cow and loot Rehoboam of Judah, but also to bring his former protégé Jeroboam of Israel to heel. It may well be (a touch of speculation, for a moment!) that Shoshenq’s price tag for helping Jeroboam into power in 931 was that Jeroboam should thereafter pay him tribute as a vassal. It would only need Jeroboam to default on his payment to bring the redoubtable pharaoh down upon him, and to lay hands on Judah’s rumored wealth for good measure.

Let’s take a step back and observe what we do have in the round. We have a pharaoh, bearing a parallel name to that of the biblical Shishak, on the scene at the very same time—the last part of Solomon’s reign to the first part of Rehoboam’s. We see him initiate an invasion of the southern Levant, right at the same time—circa 926–925 b.c.e.—conquering a large number of cities in Judah (paralleling 2 Chronicles 12:4), as well as Israel (verse 6). And perhaps most extraordinarily: Just as described in verse 7, we see no corresponding destruction layer at the most important Judean city of all. Just as promised, we see Jerusalem spared from catastrophe.

But that’s not the end of the story. Because as the passage continues to describe, the wealth of the city was plundered. And if anything is proof of Egypt’s contact with Jerusalem at this time, it is this: a sudden and colossal influx of gold and silver.

Solomon’s Gold

“So Shishak king of Egypt came up against Jerusalem, and took away the treasures of the house of the Lord, and the treasures of the king’s house; he took all away; he took away also the shields of gold which Solomon had made” (2 Chronicles 12:9). The amount of gold adorning Solomon’s temple is legendary. Various monetary estimates, based on the quantities described in the biblical account, run easily into the billions. As for silver, it “was nothing accounted of in the days of Solomon” (2 Chronicles 9:20). Many who read such accounts of the wealth and splendor of Solomon’s reign and his temple look sideways at the description of such opulence.

Just “legend,” though? Perhaps not.

From Shoshenq himself, we hear little else. He dies soon after his invasion of the Levant. But during the first years of the reign of his son and successor, Osorkon i, we suddenly see the new king lavishing temples all around Egypt in extraordinary quantities of silver and gold; this is attested to on a granite pillar inscription at the Delta site of Bubastis.

“Osorkon i gifted some 383 tons of gold and silver to the gods and temples of Egypt in the first four years of his reign, many of the detailed amounts being listed in a long inscription (now damaged),” writes Kitchen. “That sum would (in weight) be equivalent to almost 17 years of Solomon’s annual gold revenue, and perhaps to 10 years of it in gold value (not to mention such ‘minor’ items as gold shields, etc)” (ibid).

Where did such extraordinary wealth suddenly come from? It surely didn’t come from any extraordinary deeds of this new pharaoh. “No other pharaonic text remotely approaches this scale of expenditure of precious metal,” Kitchen writes.

Could such vast quantities of wealth have been derived from an already attested event in the biblical account—one that took place in the few years prior, during the reign of Shishak/Shoshenq—the total plunder of Jerusalem’s extraordinary gold reserves?

You decide.

With the wealth of Judah and Israel depleted, certain cities in smoldering ruins, and others subjugated, the stage was set for the beginning of the divided kingdom. “Sheshonq’s campaign in Israel and Judah brought an end to the many architectural, military and political achievements of the united monarchy of David and Solomon and ushered in a new age—that of the nation divided,” concludes Professor Levin (op cit).

The prophets Shemaiah and Ahijah couldn’t have said it better themselves.

Sidebar: ‘Shoshenq’ as Shishak

There is an obvious, albeit slight, difference in the names Shoshenq and Shishak. This is seen in the biblical lack of the n consonant for this name. The Bible’s שישק would, with the addition of this consonant, be rendered שישנק. (More simply, without the added mater lectionis “helper vowel” י, the names are ששק and ששנק.)

Note that the vowels are variable. Both Hebrew and Egyptian are consonantal languages, hence various acceptable spellings for both Shoshenq or Sheshonq; there is even a variant of the biblical Shishak as Shoshak or Shushak (שושק). Also note that the final k and q are equivalent letters. In fact, this biblical k is technically better transliterated as q—for it is from this particular Hebrew-Phoenician letter that our own q derives. For these reasons, Prof. Kenneth Kitchen prefers to render the biblical name Shishak as Shushaq (On the Reliability of the Old Testament).

The only real difference between the names is this biblical lack of the consonant n. When comparing the Egyptian and Hebrew texts, we essentially have the difference between Sh-sh-n-q and Sh-sh-q. Is this problematic?

Not at all. The n is what is known as a “weak consonant,” and it is not unusual for it to be dropped. Examples include the Hebrew Gat (biblical Gath) as the Egyptian Gint(i); the Hebrew Makedah as Manqedah in Aramaic; possibly also the Hebrew Put as the Egyptian Punt.

And while “Shoshenq” is the generally given Egyptian name for this king, some contemporary Egyptian monuments do actually render his name in the same manner as the Bible, without the consonant n. “These monumental inscriptions (dated to year 21 of Shoshenq’s reign) demonstrate ššq was an officially accepted variation,” wrote Gavin Cox (“Strengthening the Shishak/Shoshenq Synchrony,” 2022).