The ‘Ogdoad’ of Ancient Egypt—the Family of Noah?

The biblical account of Noah and the Flood—the watery demise of all human life, save for Noah’s family of eight and representative species of animals, all spared on the ark—is famous the world over.

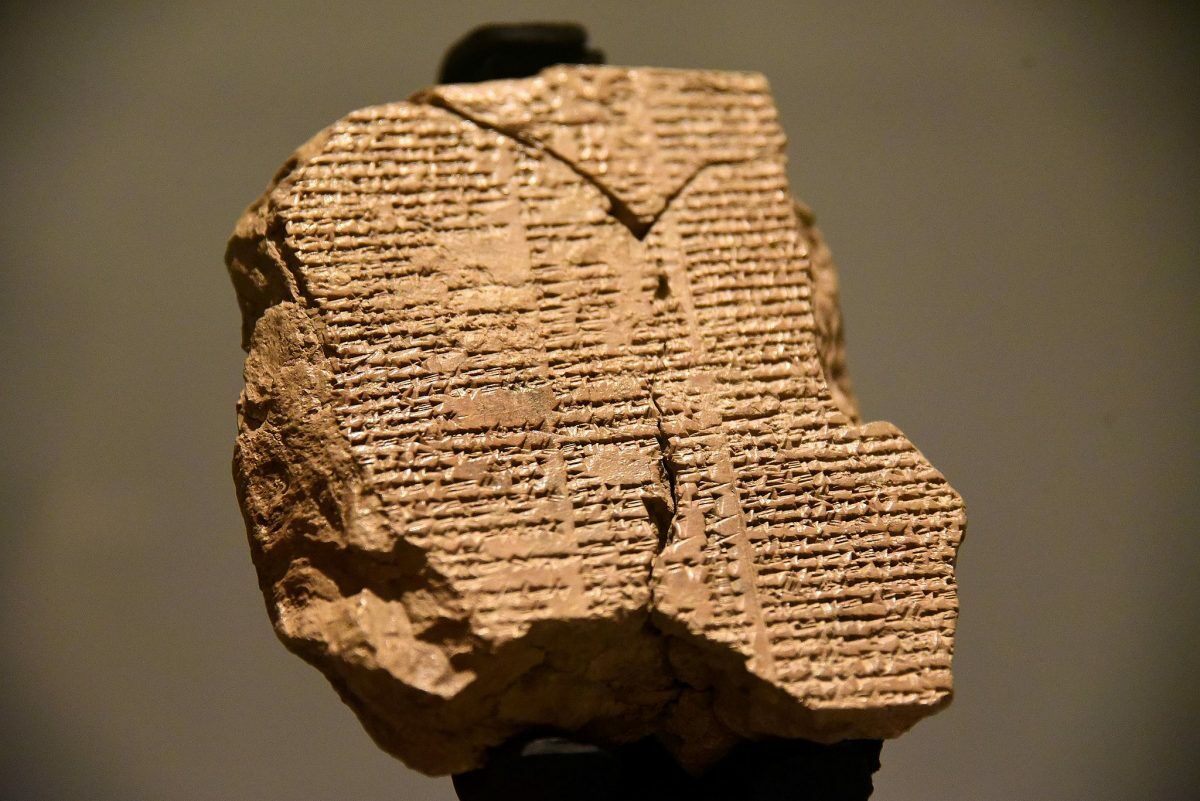

Over the past two centuries, various cuneiform texts have emerged from ancient Mesopotamia—from as early as 4,000 years ago, paralleling, in various respects, the biblical account of the climactic event (with some parallels to such a degree as the exact species of birds released from the ark window after the vessel had landed). Such Sumerian and Babylonian texts are fairly widely known, and frame the debate about whether the biblical account of the Flood derives from them (or vice versa—see the conclusion of this article). But is the biblical account of the Flood just limited to ancient Mesopotamia? What about that other great ancient civilization, to the west—is there any connection to the biblical Flood found in ancient Egypt?

There is a peculiar set of primordial Egyptian deities that bear an uncanny resemblance to Noah and his family. Could the “Ogdoad” be Egypt’s version of the biblical family of Noah?

‘The Eightfold’

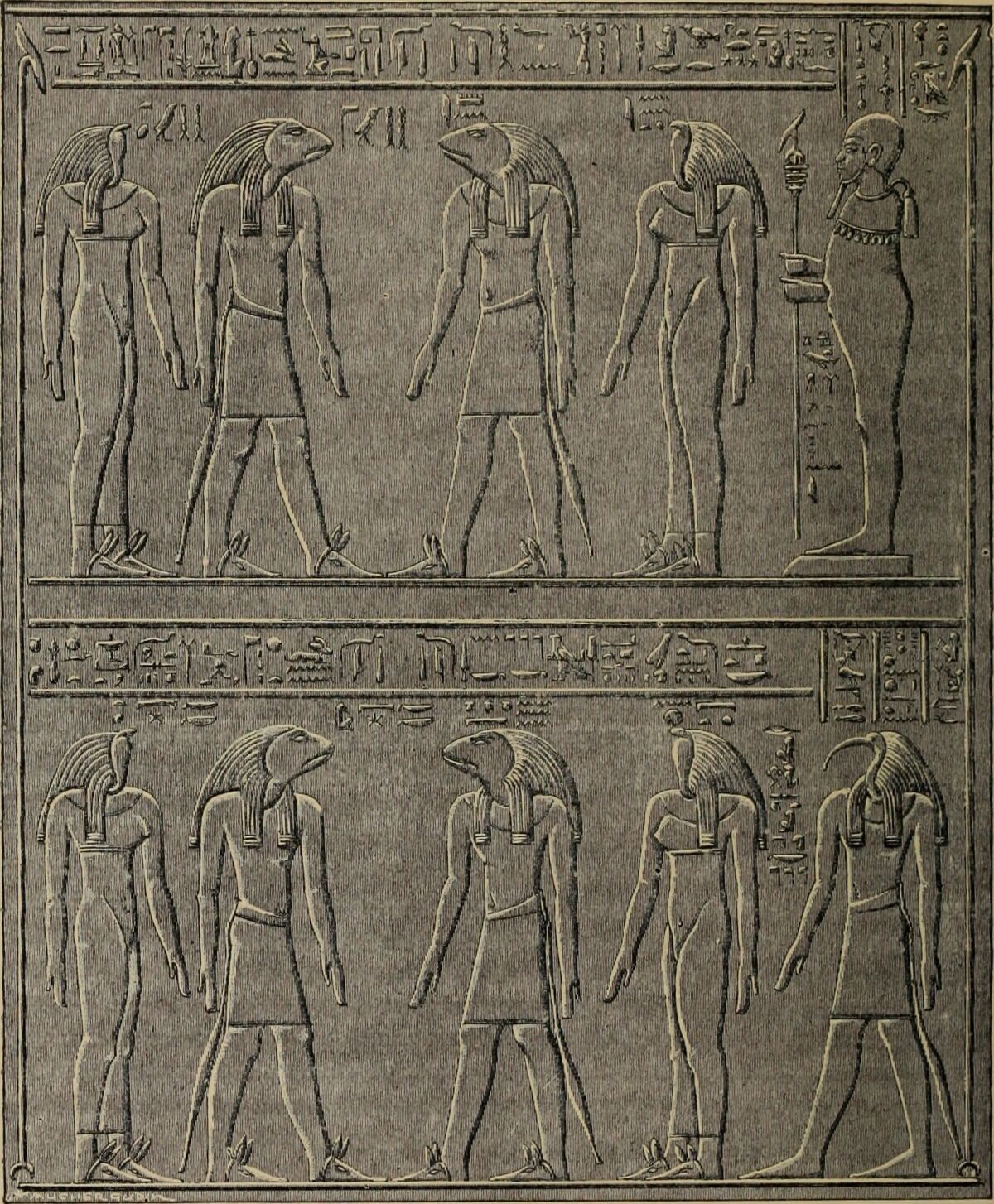

The term “Ogdoad” means “the Eightfold.” These were eight primordial Egyptian deities, consisting of four husband-wife partners. References to these eight beings go back into ancient Egypt’s earliest history—the third millennium b.c.e., Old Kingdom period. Their cult of worship was particularly centered at a site called Hermopolis. However, this later-named site (after the Greek god Hermes—a variant of the Egyptian god Thoth) was originally known as Khemenu, “City of the Eight.”

These mysterious eight deities, recognized at such an early point in Egyptian history, appear to have become sidelined during later periods. As such, comparatively little is known about them. Of course, the fact that they are eight—made up of four male-female partners—raises immediate interest, in relation to the biblical account of the eight biblical progenitors of the human race, who survived the Great Flood.

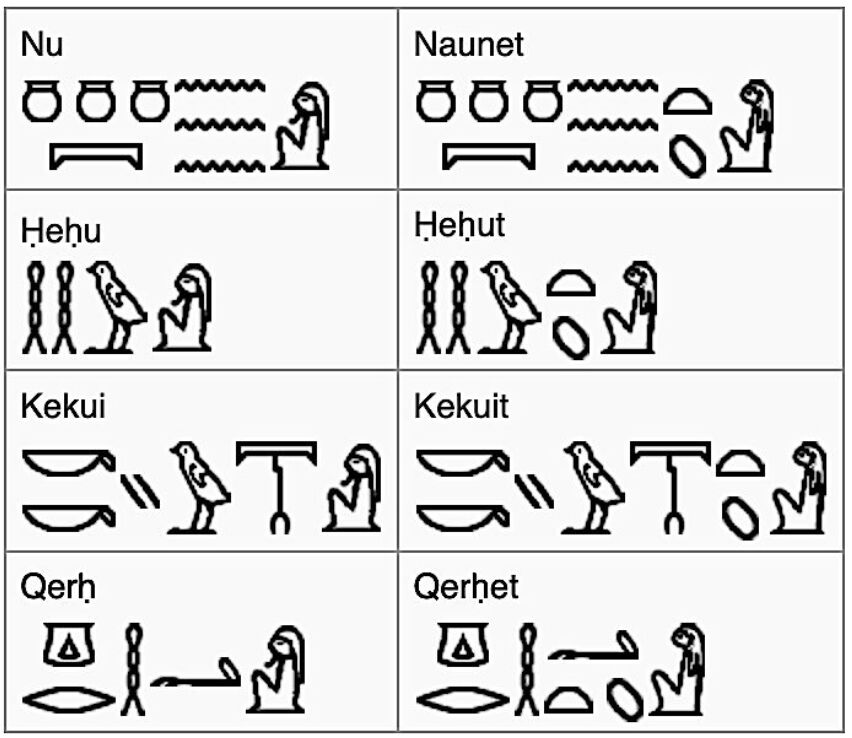

But these parallels become even more uncanny when considering the names and the setting. The names of the female deities (right-hand column, below) simply correspond as a feminine form of the male (left-hand column). But note especially the name of the leading male deity (top left).

Ancient Egyptian sources are conflicted on the meaning behind these eight primordial deities and their respective powers. Even certain of the names themselves differ, based on the source (particularly Qerh and his wife). As Egyptologist David Silverman notes in Ancient Egypt, these eight represent “the most basic qualities, enshrined in the names of the water (Nu, Nun); infinity (hhw); darkness (kkw); uncertainty (tnmw, literally ‘lostness’) or hiddenness (jmnw [alternate names for Qerh])” (page 120).

According to Gavin Cox, “The Egyptians believed the Ogdoad’s role was to maintain creation’s balance, by stopping the sky from collapsing back into the Nun (the Egyptian idea of a primeval flood), which in Egyptian cosmology was believed to be a state of chaos, from which the creation emerged” (from his 2019 article, “The Search for Noah and the Flood in Ancient Egypt”).

Egyptologist Sir E. A. Wallis Budge wrote in The Gods of the Egyptians or Studies in Egyptian Mythology (pages 287-288):

It is not easy to reconcile the various views which Egyptologists have held about the above four pairs of deities, and it certainly appears as if the ancient Egyptians themselves had no very clear ideas as to their functions. As to their antiquity there is no room for doubt … it is quite clear, from the way in which they are mentioned, that they represent traditional ideas of an extremely ancient character. One proof of this is the careful mention of the female counterparts of the four great primeval gods, for it was usual in the case of gods who were the product of the purely dynastic [later] period to pay small attention to the goddesses who were regarded as their wives. …

The general drift of the texts wherein the four pairs of gods are mentioned indicates that three pairs were qualities, or characteristics, or attributes of the fourth pair personified …. To say definitely and exactly what they represent is in the present state of Egyptological knowledge impossible, for the evidence which would enable us to arrive at a final decision in the matter is not forthcoming.

The ambiguity surrounding these eight primordial beings (the “first eight gods,” according to Budge) is interesting in its own right—and particularly the above-mentioned theory that three pairs of them are derivatives, in a sense, of the leading pair—the chief god Nu and his wife.

Nu—‘Watery Abyss’: Noah?

The name Nu, of course, immediately brings to mind the biblical Noah, father of Shem, Ham and Japheth, who brought each of their wives aboard the ark. But the similarities go further than just in the sound of his name.

You might have noticed the “wave” hieroglyphs within the names of Nu and his wife, Nut. Their names represent a watery abyss, or dually, the waters of the sky and oceans, from which ancient Egyptian tradition believed all to have been created. “The name of this god has been compared with the Coptic word noyn ‘abyss,’ ‘deep,’ and the like, and it is possible that it may have some connection with it … [as] in the passage, ‘I raised them up from out of the watery mass (nu),’” Budge wrote. “Of Nut, the female counterpart of Nu, little need be said here, except that she was regarded as the primeval mother …” (ibid).

The other individuals among the eight are much more enigmatic. Gavin Cox has an excellent, detailed two-part article series on the Ogdoad and the subject of their relation to Noah and his family (see here and here). He posits that Kek/Kekui, meaning “darkness,” relates to the biblical Ham/Kham. (Ham’s biblical name means heat; his son Cush’s name means “black.” Ham is also negatively implicated in a post-Flood account, Genesis 9:20-29.)

Cox further posits Shem as Amun (otherwise referred to in the Ogdoad as Qerh), and Japheth as Heh. Japheth’s name means “widely expanding” (Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon) and “expansion” (Strong’s Concordance). Genesis 9:27 prophesies: “God shall enlarge Japheth” (King James Version). This would be a good fit with the Ogdoad’s Heh, whose name conveys the meaning of a vast quantity, “millions” or even “infinity.”

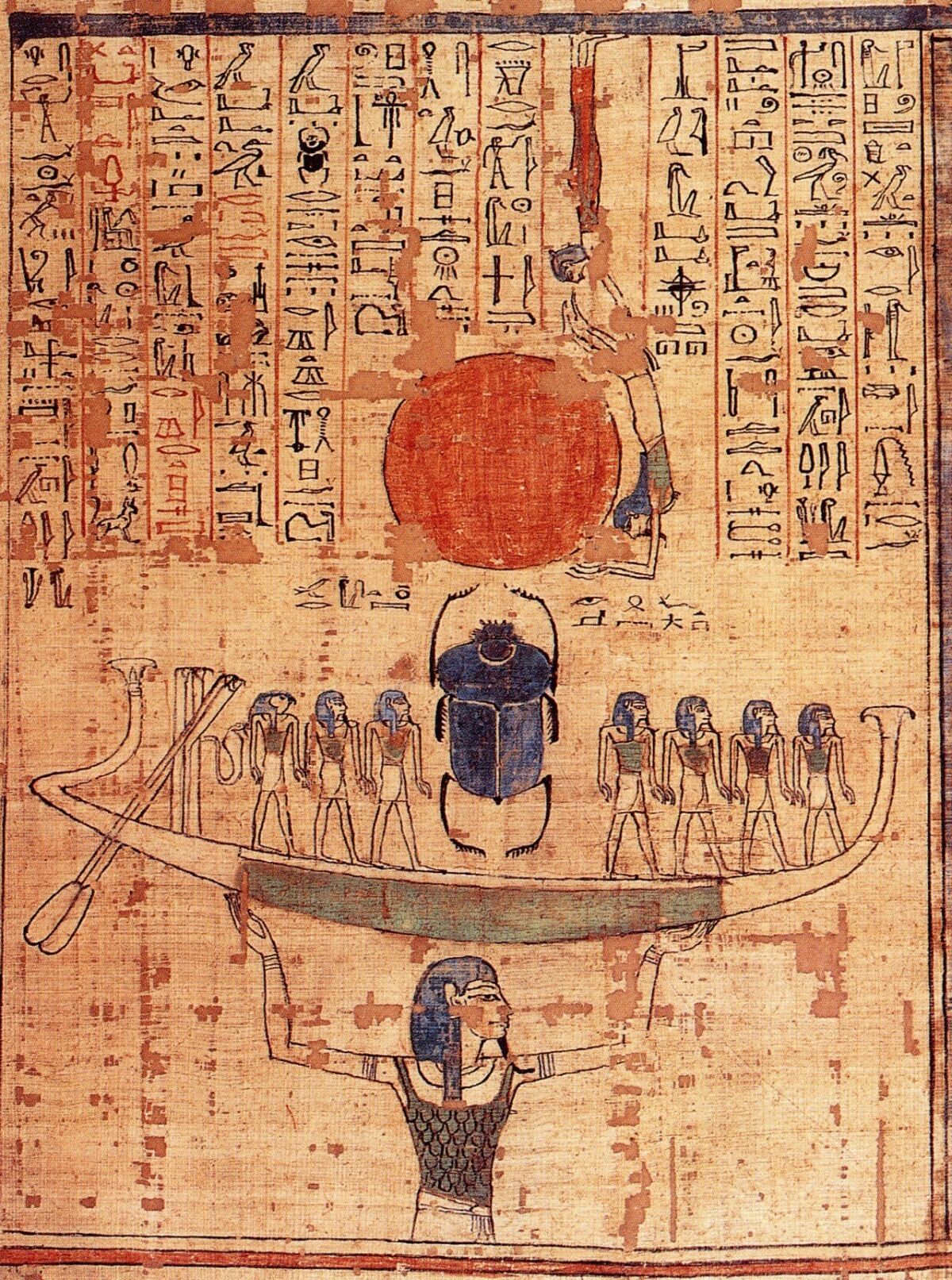

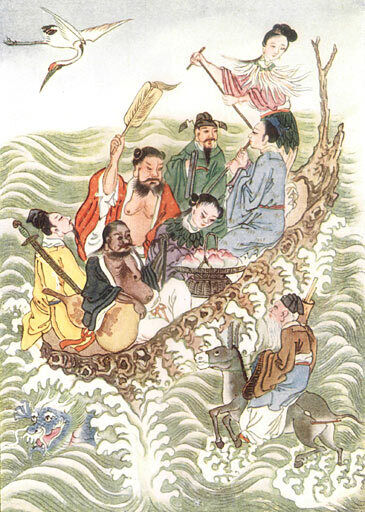

Suffice it to say, all eight deities—repeatedly called “chaos gods” in Middle Kingdom period coffin texts and led by the chief male member of the Ogdoad, Nu, “father of the gods”—are related squarely with the emergence of all mankind, and “creation” in general, from a watery abyss. Nu is often depicted holding the “solar bark,” a ship containing the other seven gods of the Ogdoad. (In Egyptian mythology, Nu’s separation of the sky and waters allows the sun-god Ra to sail his solar bark through the sky. The association of Nu and the Ogdoad with such a vessel is fascinating in its own right.)

“From the biblical text, Egypt should be understood as a post-Babel civilization (Genesis 11:1-9),” wrote Cox. “If Noah, his family and the Flood are recorded in secular history, we should expect to see evidence in Egypt’s earliest writings.” He argues that references to “the Eightfold” emerging during Egypt’s late third millennium b.c.e., Old Kingdom period provide this evidence. He further notes that given the sheer lifespans of these individuals given in the biblical account, having survived the Flood and outliving even many of those initially born post-Flood, it would be unsurprising for them to have been deified among the post-Flood world (though they are of course very human in the biblical account).

Common Theme—the World Over

Perhaps such an uncanny Noah/Flood-like association from ancient Egypt should be unsurprising. After all, some form of this event is found all over the globe, to the point where it could almost be termed a “cultural universal.”

Again, archaeology has revealed ancient parallel accounts among Mesopotamian civilizations. Parallels are also found in the Greek world, with the survival of Deucalion and his wife aboard an ark. There’s an ancient Chinese Flood myth, featuring a central character, Nüwa. There’s the Hindu tale of Manu and the flood, various Irish and Welsh flood myths, Finnish and Norse blood-deluge myths, numerous African flood myths, Pacific flood myths and ancient American flood myths.

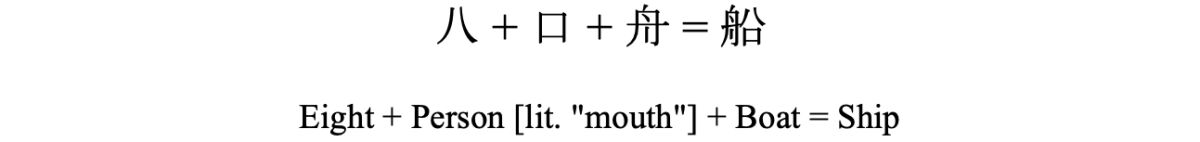

China’s own famous “Eight Immortals,” themselves symbols of “longevity,” were famous for crossing the sea (and even popularly associated with a tale of drunkenness—compare with Genesis 9:20-24). And the very Chinese word for “ship” is a character made up of radicals meaning “eight-person-boat.”

In “Why Does Nearly Every Culture Have a Tradition of a Global Flood?,“ Dr. John Morris described his collection and analysis of more than 200 accounts of floods, originally reported by missionaries, anthropologists and ethnologists. He wrote: “While the differences are not always trivial, the common essence of the stories is instructive, as compiled below:

- Is there a favored family? 88 percent

- Were they forewarned? 66 percent

- Is flood due to wickedness of man? 66 percent

- Is catastrophe only a flood? 95 percent

- Was flood global? 95 percent

- Is survival due to a boat? 70 percent

- Were animals also saved? 67 percent

- Did animals play any part? 73 percent

- Did survivors land on a mountain? 57 percent

- Was the geography local? 82 percent

- Were birds sent out? 35 percent

- Was the rainbow mentioned? 7 percent

- Did survivors offer a sacrifice? 13 percent

- Were specifically eight persons saved? 9 percent.”

Where did these shared accounts come from? Though many may balk at the conclusion, Morris—a Bible-believer—concludes his article, writing:

The only credible way to understand the widespread, similar flood legends is to recognize that all people living today, even though separated geographically, linguistically and culturally, have descended from the few real people who survived a real global flood, on a real boat which eventually landed on a real mountain. Their descendants now fill the globe, never to forget the real event.

A common idea points to a common experience. And the concept of a Great Flood must be one of the most common in human history. Many scoff at the biblical account of a Great Flood. Yet it has been preserved in varying forms by numerous civilizations around the globe. Dismissal out of hand would be naïve. What must have happened to trigger the recording of such stories? Perhaps some form of a great flood really did happen—one that would have thus left a significant historical and cultural mark on all mankind—not just on the Israelites of the Bible, but also on Mesopotamia, Egypt—and beyond?