Did the Israelites Really Live in Egypt?

The Bible describes Israel’s time in Egypt in remarkable and vivid detail. It tells us roughly when the Semitic descendants of Abraham arrived in Egypt and where they settled. It tells us what the Israelites did while in Egypt and describes their interactions with the Egyptians. Finally, the Bible gives us a good indication of when Israel left Egypt and the dramatic events surrounding the Exodus.

Although the biblical text clearly and explicitly documents Israel’s sojourn in Egypt, some scholars reject the idea that the Hebrews ever dwelt in Egypt. One primary reason they reject this biblical account as fiction is because of a purported lack of archaeological evidence. “The Exodus is so fundamental to us and our Jewish sources that it is embarrassing that there is no evidence outside of the Bible to support it,” wrote archaeologist Stephen Rosenberg in the Jerusalem Post (April 14, 2014).

Is that true? Is there really no evidence outside of the Bible to support Israel’s sojourn in Egypt and the Exodus?

Before we answer, it’s helpful to appreciate why evidence of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt can be hard to come by. First, many archaeologists simply cannot agree on when the Israelites were in Egypt. Second, only a tiny fraction of ancient Egypt has been excavated in controlled excavations. Third, slaves do not usually leave behind scads of evidence. Fourth, the ancient Egyptians are infamous for blotting out embarrassing historical events that would tarnish their reputation (which would certainly include the Exodus).

There’s also the challenge of the location in which the Israelites lived: Goshen, within the Nile Delta. “The Delta is an alluvial fan of mud deposited through many millennia by the annual flood of the Nile; it has no source of stone within it,” writes Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen. “[M]ud-brick structures were of limited duration and use, and were repeatedly leveled and replaced, and very largely merged once more with the mud of the fields. So those who squawk intermittently, ‘No trace of the Hebrews has ever been found’ (so of course, no Exodus!), are wasting their breath. The mud hovels of brickfield slaves and humble cultivators have long since gone back to their mud origins ….

“Even stone structures (such as temples) hardly survive …. [In this region] 99 percent of discarded papyri have perished forever; a tiny fraction (of late date) have been found carbonized …. Otherwise, the entirety of Egypt’s administrative records at all periods in the Delta is lost, and monumental texts are also nearly nil” (On the Reliability of the Old Testament).

Despite these significant challenges, there is actually a reasonable amount of compelling evidence testifying to Israel’s time in Egypt.

Following are 10 points of evidence. While not every item on this list is irrefutable, the combination of them, in parallel to the biblical record, ought to be enough to cause any open-minded person to at least recognize that there is significant evidence to support the biblical account of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt.

1. The Ibscha Relief

The Bible mentions several “migrations” of the patriarchs into Egypt, particularly to escape famine events. While Canaan relied on consistent rainfall and was susceptible to drought, the Nile River largely alleviated the threat of drought in Egypt.

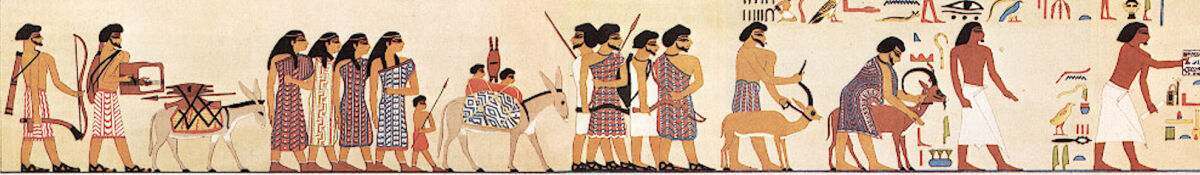

The Ibscha Relief is a famous tomb painting discovered at the site of Beni Hassan, an ancient Egyptian mortuary complex on the eastern banks of the Nile River in central Egypt. Belonging to the mid-19th-century b.c.e. tomb of Governor Khnumhotep ii, this painting depicts a train of Asiatic (Semitic) men, women and children with goods, wearing unusual, bright, multicolored garments, arriving in Egypt from either Canaan or somewhere in the vicinity. The Semites are distinguished in detail by their skin color, hair, beards and clothes, as well as by items on their person (one individual is holding a harp). “This scene is unique in the repertoire of Egyptian funerary art,” explained Egyptologist Janice Kamrin. “Its unusual nature, and the apparent accuracy of its details, renders it very likely to be a representation of, or at least an allusion to, a specific event” (“The Aamu of Shu in the Tomb of Khnumhotep ii at Beni Hassan”).

Along with the painting is an inscription that identifies one of the leaders of the procession with a Semitic name and the earliest use of a peculiar title: “Abisha the Hyksos.” The people themselves are labeled the “Aamu of Shu.” Debate continues as to the meaning of this title. Am is the most common Hebrew word for “people” or “nation” in the Bible. Whatever the exact meaning, “[t]he bulk of scholarly opinion would thus place the homeland of the Aamu of Shu in the southern Levant,” wrote Kamrin—in other words, in or around Canaan.

While the timing of the migration doesn’t match with Jacob, it would be a good fit for his grandfather Abram’s journey to Egypt, as recorded in Genesis 12:10 (see the following article for more information on the dating of Israel’s entry into Egypt).

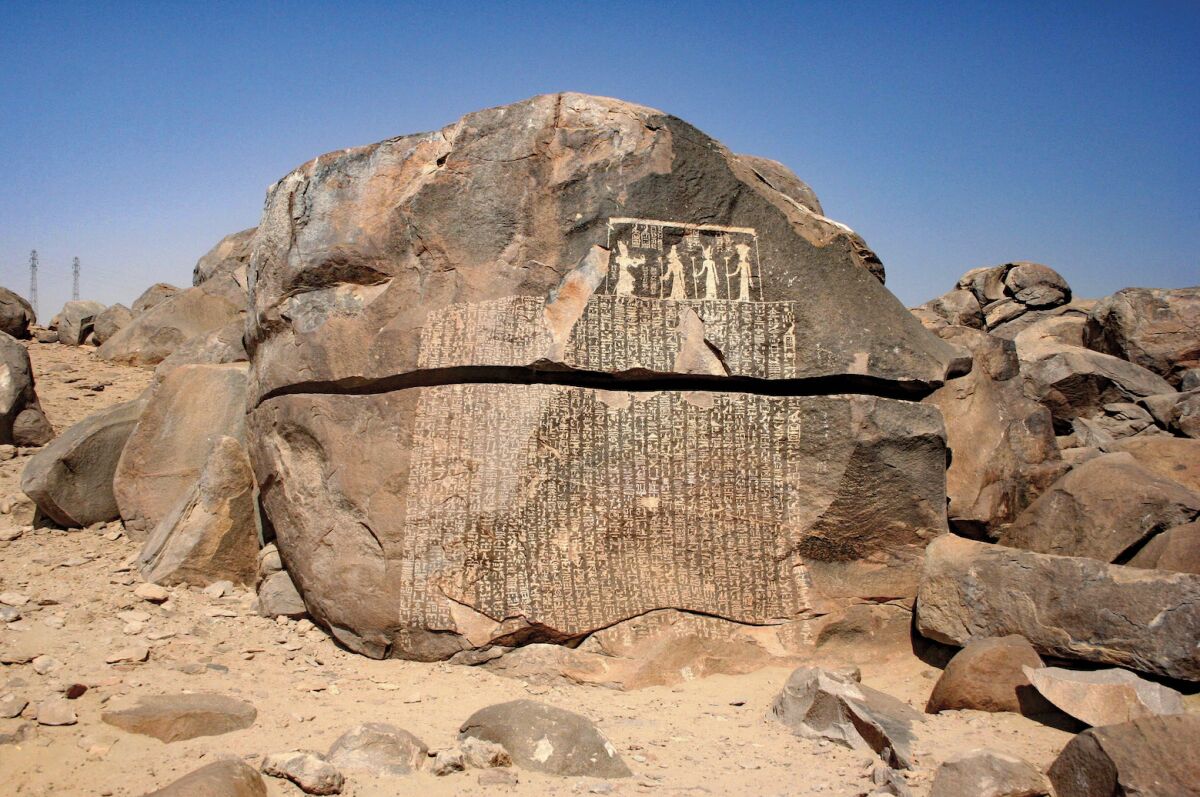

2. Famine Stele

The Famine Stele is a mammoth boulder inscription found on Sehel Island in the Nile River. The inscription is carved in Ptolemaic Egyptian script, probably as late as either the third or second century b.c.e. It recounts a story from Egypt’s distant past of a famine “in a period of seven years. Grain was scant, kernels were dried up, scarce was every kind of food. … Children cried, youngsters fell, the hearts of the old were grieving; legs drawn up, they hugged the ground, their arms clasped about them. Courtiers were needy, temples were shut, shrines covered with dust, everyone was in distress” (emphasis added).

The account proceeds to describe a dream had by the pharaoh for which an answer was provided, in which the “father of the gods” would “make the Nile swell, without there being a year of lack and exhaustion in the whole land, so the plants will flourish, bending under their fruit. … [E]verything will be brought forth by the million and […] in whose granary there had been dearth. The land of Egypt is beginning to stir again.”

This account is generally attributed to the reign of Djoser, an early pharaoh traditionally dated to the mid-third millennium b.c.e. Of course, the actual inscription itself was carved thousands of years later. Actually, the account reads remarkably like the one in Genesis 41-47—Egypt suffering “seven years of famine” (the problem—and solution—revealed through a pharaoh’s dream, no less). It is against this backdrop that Joseph provides the interpretation to the pharaoh’s dream, is raised in rank, and ultimately paves the way for Israel’s descent into Egypt.

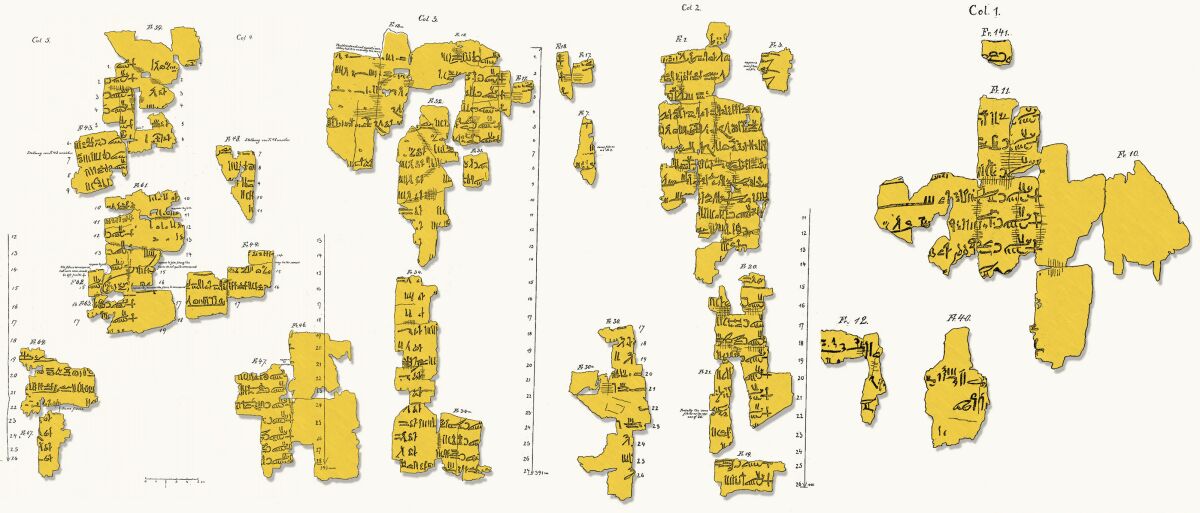

3. Turin and Manetho King Lists: Rise of the Hyksos

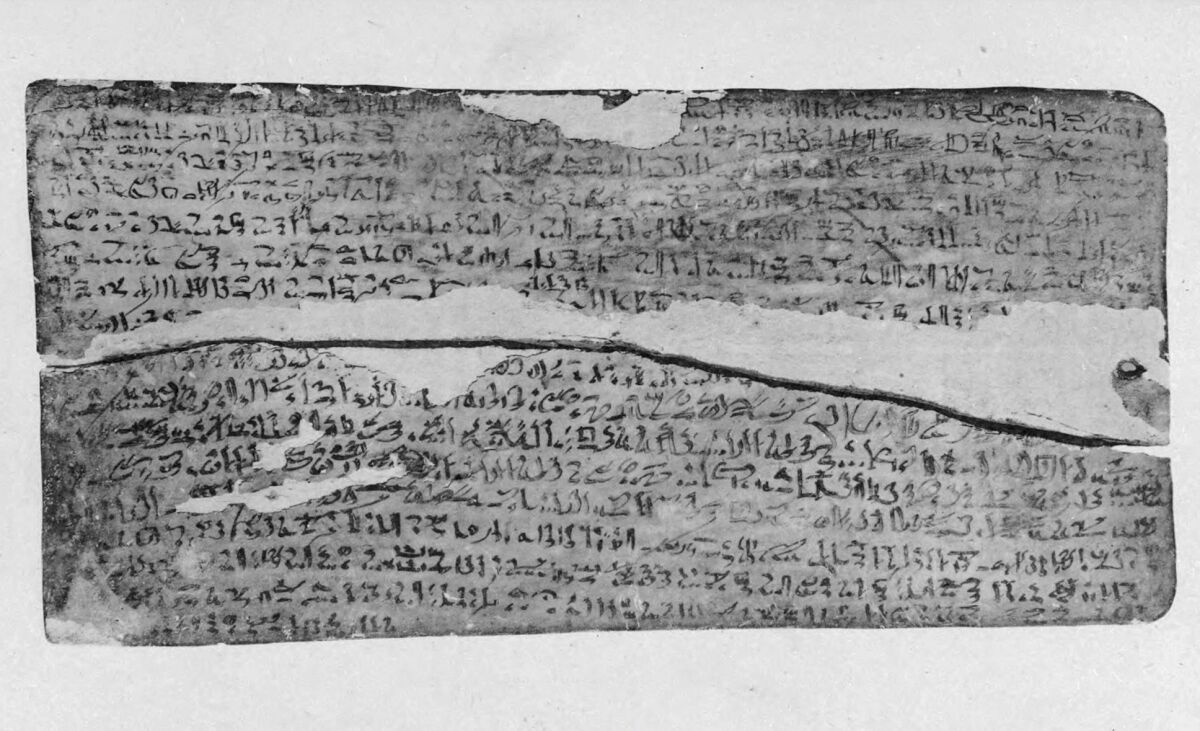

The Turin King List is an ancient document created during the 13th-century b.c.e. reign of Pharaoh Ramesses ii, listing earlier Egyptian rulers. Written on papyrus, this list was discovered at Thebes in 1820 by Bernardino Drovetti, an Italian traveler. Although roughly 50 percent of the papyrus is missing, the names on the Turin King List provide insight into the pharaohs who ruled Egypt during its 15th Dynasty period—the “Hyksos Dynasty.”

This period is particularly elusive in Egyptian annals. While several other king lists have survived (such as the Saqqara Tablet, the Abydos King List, the Karnak King List, the Medinet Habu King List and the Palermo Stone), only the Turin King List records Egypt’s rulers during this crucial and fascinating period. Later Egyptian pharaohs erased the history of this dynasty. “Even today, in particular, there are not found any Hyksos written texts, inscriptions and bas-reliefs, tombs, frescoes or sculptures,” wrote historian Evgenii Misetskii. “Everything that could somehow remind of the power of the Hyksos was destroyed in the country by order of the New Kingdom pharaohs” (“From Joseph to Moses: The Key Time of Interaction Between the Cultures of Egypt and Israel”).

Why did later pharaohs attempt to erase the Hyksos from Egyptian history? The Hyksos were a group of immigrant Semitic rulers from the region of Canaan who rose to prominence in the northern Delta region of Egypt for a roughly 100-year period, around the 17th to 16th centuries b.c.e. Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian—based on the writings of the third-century b.c.e. Egyptian historian Manetho—directly identified these “Hyksos” as the Israelites and pointed out an interpretation of the name as meaning “shepherd kings.”

“[T]his nation, thus called shepherds, were also called captives, in their sacred books,” Manetho wrote. Manetho’s king list enumerates six Hyksos rulers. The first is Salitis; Manetho described him in the context of coming down into Egypt and gathering corn (compare with the actions of Joseph in Genesis 41:49). This name, Salit (removing the suffix -is, a typically added Greek suffix—note that Manetho and Josephus both wrote in this language), is identical to a unique title given to Joseph as ruler over Egypt. Genesis 42:6 states that “Joseph was the governor over the land.” This word is not the ordinary one used for “governor” in the Bible. Instead, it’s the unique word salit—thus, “Joseph the Salit.”

The succeeding ruler on Manetho’s Hyksos king list is Bnon, or Benon. This matches closely with the name of Benjamin—in fact, more closely than at first meets the eye. That’s because Benjamin had two names—the first given to him by his mother, Rachel, just before she died after childbirth: Benoni (Genesis 35:18). Benjamin, Jacob’s youngest son and Joseph’s only full brother, would have been a logical successor to Joseph’s authority. Genesis 43:34 and 45:22 describe Joseph honoring Benjamin above his other brothers in the Egyptian court with five times the food, five times the apparel and great riches.

4. Archaeologically Attested Hyksos Leaders

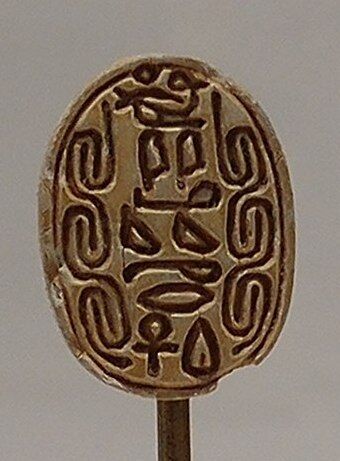

Besides the general Turin and Manethonian king lists, separate specific archaeological evidence of certain leading Hyksos figures has been discovered.

One of these especially prominent Hyksos individuals is a man known from nearly 30 royal scarab seals found primarily throughout Canaan but also in Egypt. These scarabs, believed to date to the 17th century b.c.e., bear the name Yaqub-har.

Yaqub is the exact transliteration of the Semitic name Jacob. The “har” in Yaqub-har is also a Hebrew-Semitic word that can mean hill, mount or mountain. This word is connected with Jacob several times in the Bible (Genesis 31:25, 54; Isaiah 2:3). It may have constituted some kind of a familial suffix or “surname” among the Hyksos (as is also attested by the next name). The jury is still out among scholars as to whether Yaqub-har was a Hyksos “king” in his own right or simply a highly regarded official. Naturally, the latter would best fit the biblical account.

Another high-ranking Hyksos official is known from a single inscription found on a doorjamb at Tell el-Dab’a. This individual’s name, similarly suffixed, is Sakir-har. The word sakir means “reward.”

This name closely parallels that of Jacob’s son Issachar. The biblical name Issachar, or Is-Sakir, means “there is a reward.” The Bible relates that his mother Leah proclaimed when she bore him: “‘God has granted me a reward [sakar] ….’ So she named him Issachar” (Genesis 30:18; New English Translation).

5. Tell el-Dab’a

Classical historians record that the capital city of the Hyksos dynasty was called Avaris. Josephus, relying largely on Manetho, relays a significant amount of information about Avaris as Israel’s “capital” while in Egypt. He recorded that Avaris was the “ancient city and country” bequeathed to the Hyksos by Egypt. (Even the name of the site bears resemblance to the root of the word “Hebrew,” avar, suggesting a naming after the people who lived there.)

Archaeologists have identified the ruins of Tell el-Dab’a in northern Egypt with ancient Avaris (fitting with the biblical location of the land of Goshen). Excavations at the site have revealed evidence of a clearly foreign, Semitic population, with housing styles similar to that of Canaan, along with Levantine-style weapons and pottery. They also found animal remains, notably excluding pig, leading excavators to speculate that some form of “kosher” system was in place. Large food-storage silos were also discovered at the site.

Much has also been made of a palatial complex within the site containing 12 tombs. One of them is much grander than the others, yet lacks any human remains (compare with Genesis 50:25). A good amount of attention was given to this in Patterns of Evidence: The Exodus—in particular, to an unusual statue and tomb Egyptologist David Rohl identifies with Joseph.

https://youtu.be/rESYeIRKYMk?t=61

Also notable is when this city ceased to function. As archaeologist Dr. Scott Stripling notes, “Bietak’s stratigraphic analysis [of Tell el-Dab’a] reveals a clear abandonment in the mid-18th Dynasty, during or after the reign of Amenhotep ii. … [T]he latest identifiable pottery dates to the reign of Amenhotep ii …” (Five Views on the Exodus: Historicity, Chronology and Theological Implications).

6. Carnarvon Tablet

The Carnarvon Tablet is a mid-16th-century b.c.e. wood-and-plaster inscription discovered in 1908 adjacent to the entrance to a tomb near the Deir el-Bahari mortuary complex. The text belongs to the native Egyptian pharaoh of Upper (southern) Egypt, Kamose.

The text reveals that Kamose feared the Hyksos were getting too powerful and needed to be overthrown. It reads in part: “I should like to know what serves this strength of mine, when a chieftain is in Avaris, and another is in Ethiopia, and I sit united with an Asiatic [Hyksos/Semite] and a Nubian, each in possession of his slice of Egypt …. No man can settle down, when despoiled by the taxes of the Asiatics. I will grapple with him, that I may rip open his belly! My wish is to save Egypt and to smite the Asiatic [Hyksos]!”

The text and geopolitical scene is uncannily reminiscent of Exodus 1:8-10: “Now there arose a new king over Egypt, who knew not Joseph. And he said unto his people: ‘Behold, the people of the children of Israel are too many and too mighty for us; come, let us deal wisely with them ….’”

Kamose did not live to see the complete overthrow of the Hyksos—he was killed by a blow from a Hyksos soldier while in battle. The northern land of Lower Egypt would finally be subdued by his successor, Ahmose i.

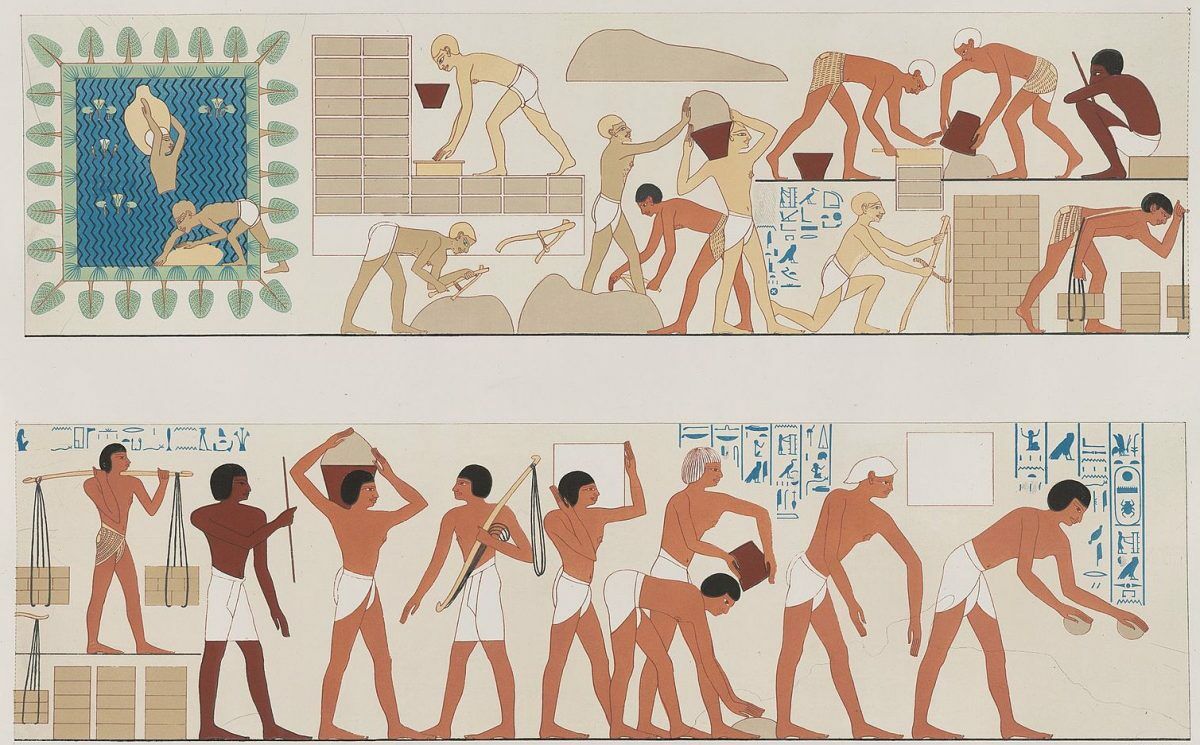

7. Rekhmire’s Tomb

Depictions of slaves in subsequent decades to Ahmose i’s reunification of Egypt have been found at multiple sites in Egypt. On the walls of the Tomb of Rekhmire (the mid-15th-century b.c.e. vizier for Thutmose iii and Amenhotep ii), painted images depict light-skinned Semitic slaves making bricks out of mud, water and chaff. The Bible also records the Hebrews making bricks in Egypt: “And the Egyptians made the children of Israel to serve with rigour. And they made their lives bitter with hard service, in mortar and in brick …” (Exodus 1:13-14). And, “Ye shall no more give the people straw to make brick, as heretofore. Let them go and gather straw for themselves” (Exodus 5:7).

Another scene in the tomb contains an inscription reading as follows: “Rejoice, O prince, all your affairs are flourishing. The treasure stores are overflowing.” This fits well with the biblical account of the Israelites building treasure stores, or “treasure cities,” for the pharaoh (Exodus 1:11; King James Version).

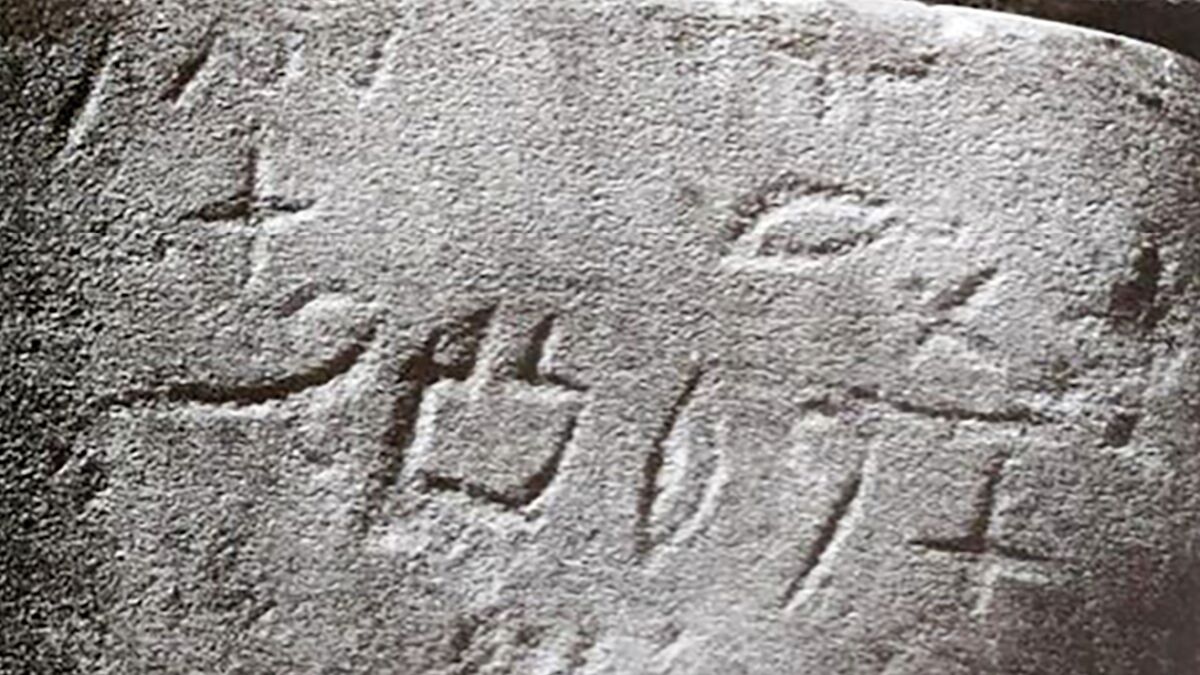

8. Serabit el-Khadim

While the biblical account highlights the slavery of brickmakers, numerous classical accounts also make reference to the Israelites being sent to work in mines (see “Exodus Outside of the Bible: The Classical Accounts” for more information). Serabit el-Khadim was a sporadically operated Egyptian turquoise mine on the western side of the Sinai Peninsula, in operation between the 19th and 15th centuries b.c.e. The site included significant worship of the Egyptian cow-goddess, Hathor, as well as evidence of the presence of Semitic slaves.

In 1905, Sir William F. Petrie discovered examples of early alphabetic script at Serabit el-Khadim. These “proto-Sinaitic” inscriptions, dating more specifically to the 16th–15th centuries b.c.e., are a precursor to the Hebrew alphabet (and other Levantine languages).

Prof. Douglas Petrovich goes further; he has proposed translations for several of these inscriptions, which he calls “Old Hebrew,” based on uniquely Hebrew elements. He identifies certain names, including “Moses,” “Ahisamach” (father of Oholiab; Exodus 31:6), and “Asenath” (Joseph’s wife; Genesis 41:45), as well as “Hebrews of Bethel” (described in his book The World’s Oldest Alphabet: Hebrew as the Language of the Proto-Consonantal Script; his conclusions, naturally, have been controversial). Specifics of translation aside, the inscriptions point to a Hebrew-related slave operation at the site during the 16th to 15th centuries b.c.e., alongside a setting of cow worship in the same general geographic location that cow worship reappears in the biblical account, during the Israelite sojourn in the Sinai wilderness (Exodus 32).

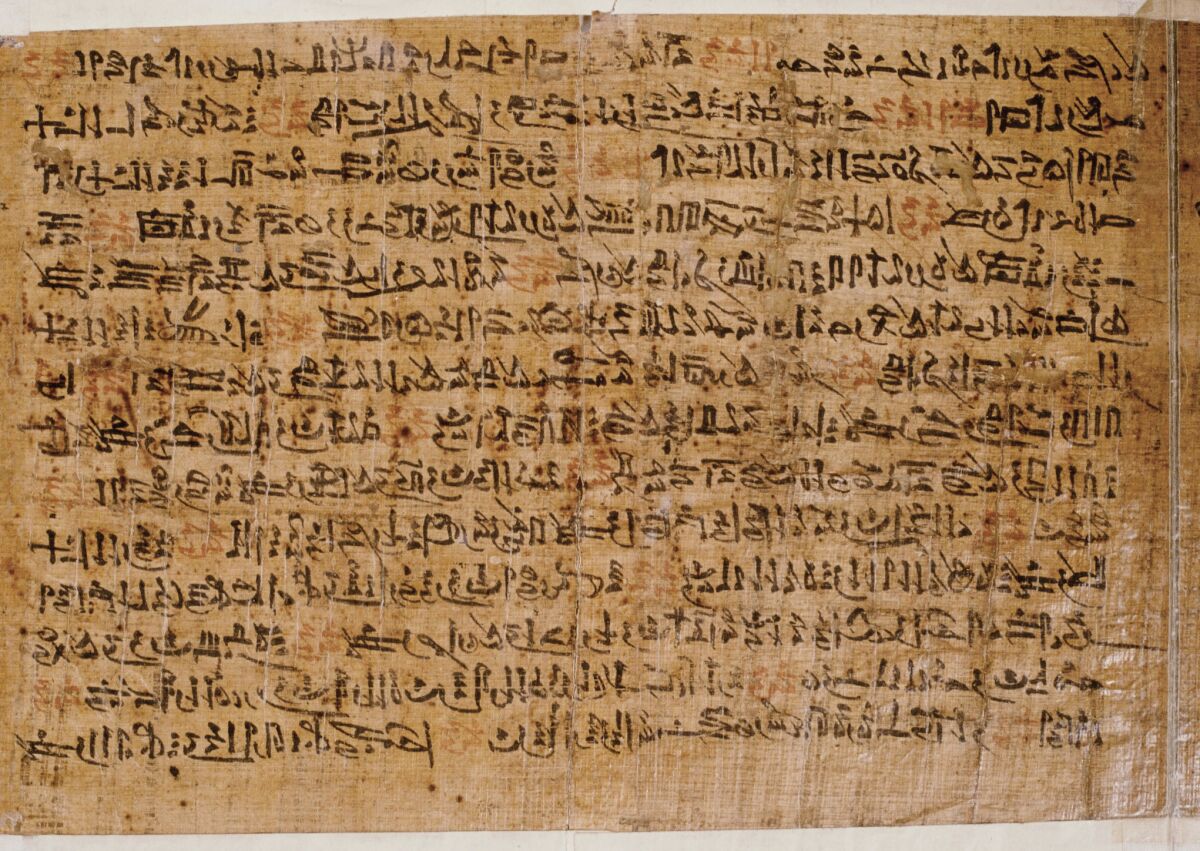

9. Ipuwer Papyrus

The Ipuwer Papyrus is a scroll dated to the 13th century b.c.e. Written in the hieratic text, it is believed to be a copy of a centuries-earlier account (exactly when is debated). Ipuwer was the name of a royal Egyptian scribe and was a common Egyptian name in the mid-15th century b.c.e. On the papyrus, the scribe records a series of disasters that struck Egypt. The resemblance of these catastrophes to the biblical plagues of Egypt is striking. Below are some examples of parallels between the papyrus and the biblical text:

Ipuwer: Indeed, the river is blood, yet men drink of it.

Exodus 7:20: [A]nd all the waters that were in the river were turned to blood.

Ipuwer: Indeed, [hearts] are violent, pestilence is throughout the land, blood is everywhere, death is not lacking ….

Exodus 9:15, 7:19: Surely now I had put forth My hand, and smitten thee and thy people with pestilence …. [A]nd there shall be blood throughout all the land of Egypt ….

Ipuwer: Indeed, magic spells are divulged; smw- and shnw-spells are frustrated ….

Exodus 8:14: And the magicians did so with their secret arts … but they could not ….

Ipuwer: Indeed, all animals, their hearts weep; cattle moan ….

Exodus 9:3: Behold, the hand of the Lord is upon thy cattle … there shall be a very grievous murrain.

Ipuwer: Indeed, everywhere barley has perished ….

Exodus 9:31: And the flax and the barley were smitten ….

Ipuwer: The land is without light ….

Exodus 10:22: [A]nd there was a thick darkness in all the land of Egypt ….

Ipuwer: Indeed, every dead person is as a well-born man …. Indeed, the children of princes are dashed against walls ….

Exodus 12:29: [T]he Lord smote all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, from the first-born of Pharaoh that sat on his throne unto the first-born of the captive ….

Ipuwer: Indeed, men are few, and he who places his brother in the ground is everywhere ….

Exodus 12:30: [T]here was not a house where there was not one dead.

Ipuwer: Indeed, poor men have become owners of wealth, and he who could not make sandals for himself is now a possessor of riches …. Indeed, gold and lapis lazuli, silver and turquoise … are strung on the necks of maidservants ….

Exodus 12:35, 11:2: And the children of Israel … asked of the Egyptians jewels of silver, and jewels of gold, and raiment. … [E]very woman [took] of her neighbour, jewels of silver, and jewels of gold.

Ipuwer: Indeed, noblemen are in dis- tress, while the poor man is full of joy.

Exodus 14:8: [F]or the children of Israel went out with a high hand.

Ipuwer: [Behold, he who did not know his god] now offers to him with incense of another ….

Exodus 6:3; 10:25: [B]y My name yhwh I made Me not known to them. … And Moses said [to Pharaoh]: ‘Thou must also give into our hand sacrifices and burnt-offerings, that we may sacrifice unto the Lord our God.

The papyrus levels thinly veiled blame at those who allowed what it identifies as troublesome shepherds into the land of Egypt: “What the ancestors foretold has arrived …. [M]en say: ‘He is the herdsman of mankind, and there is no evil in his heart.’ Though his herds are few, yet he spends a day to collect them, their hearts being on fire. Would that he had perceived their nature in the first generation; then he would have imposed obstacles, he would have stretched out his arm against them, he would have destroyed their herds and their heritage.”

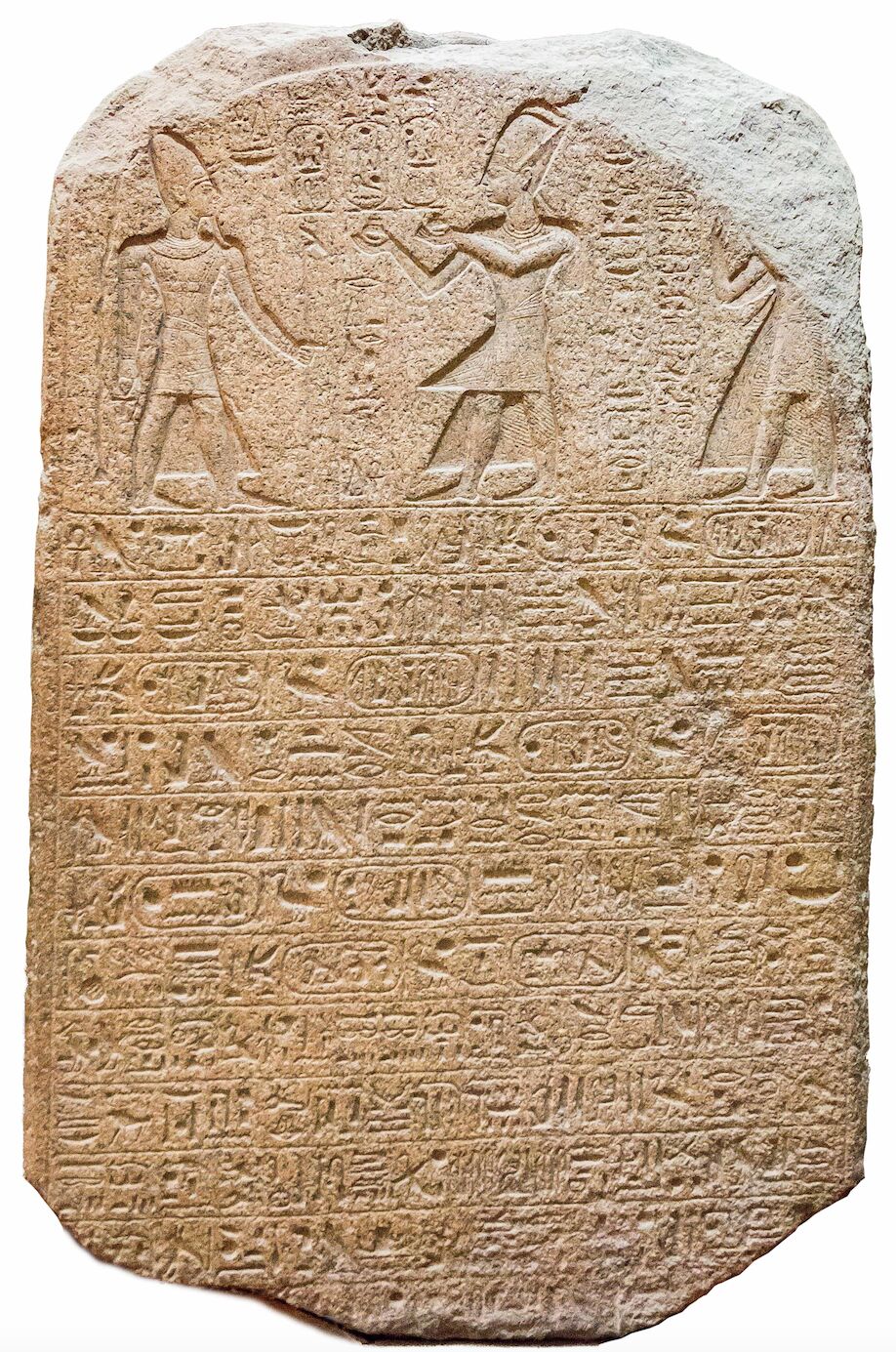

10. 400-Year Stele

The “400-Year Stele” is an incredibly enigmatic, large granite monument discovered at Tanis in the year 1863. Installed with permission by an official named Seti during the 13th-century b.c.e. reign of Ramesses ii, the partial inscription of the broken stele highlights a 400-year period of the distant past—though the celebration of what, exactly, is unclear. What is more evident is its connection to Hyksos history.

Egyptologist Peter Feinman wrote of this “400-Year Stele of Ramesses ii, honoring the legacy of the Hyksos,” noting that Bible scholar “Baruch Halpern suggests that if the Israelite scribes knew of the 400-Year Stela, that such knowledge is evidence of the portrayal of Israel as Hyksos …” (described further in “The Hyksos and the Exodus: Two 400-Year Stories”). He further highlighted Egyptologist Jan Assmann’s assessment that the stele “represents the first—and for a long time remained the only—instance of a historical anniversary recorded in the annals of history.”

And a 400-year period, it turns out, is of particular biblical significance to this Israelite sojourn. In Genesis 15, God informs Abraham of what will befall his descendants: “Know of a surety that thy seed shall be a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them; and they shall afflict them four hundred years” (verse 13).

Want More Evidence?

In this article we’ve reviewed 10 major threads of evidence pointing to the historicity of the biblical account of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt. Yet these are not even the strongest proof we have that the Israelites dwelled in Egypt.

The greatest proof we have is the Bible itself, which contains a plethora of details about Egypt in the Middle/Late Bronze Age. The Torah contains remarkably accurate details about very specific Egyptian phraseology, names, geography, flora and fauna, and Israelite laws concerning practices that were extant in Egypt at the time. When you consider just how intimately familiar the Torah is with Egypt, it is evident that it had to be written by someone who lived in Egypt—someone who lived the history recorded in the book of Exodus. To learn more about this, read our articles “Searching for Egypt in Israel” and “Evidence of the Exodus?”