What Does the Name ‘Sarai’ Really Mean?

The meaning of the name “Abraham,” as changed from “Abram,” has—as we covered in a recent article—been the subject of an enormous amount of debate over the centuries. The word in its totality, Ab-ra-ham, doesn’t appear to make sense—in Hebrew, that is. Numerous commentaries have struggled with not only the name but also the reason for the change, with a common proposition being that the names Abram and Abraham are essentially the same (e.g. The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible: “basically identical in form and meaning”). As covered in the earlier article, there is not only good reason for the name change—with the former and latter names each having an entirely different meaning—but also for the apparent ambiguity, tied directly to the foreign and sojourning nature of the patriarch.

But ditto for the name of Abraham’s wife. Many are familiar with her name change, also contained within the 17th chapter of Genesis: “And God said unto Abraham: ‘As for Sarai thy wife, thou shalt not call her name Sarai, but Sarah shall her name be” (verse 15).

From the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia: “‘Sarah’ and ‘Sarai’ are identical in meaning; it is difficult to understand the reason for the change.”

As we covered with Abram/Abraham, is that really a sufficient answer?

Sarah—Check

A fairly standard interpretation of the meaning of the two names, Sarai (שרי) and Sarah (שרה), is that they center around the root word sar (שר), meaning “prince” (or similarly, “chief,” “leader” or “captain”). This seems logical—and in this “debate,” interpretation of the name Sarah is straightforward. It is the feminine form (with the -h, ה ending) of the masculine sar (שר), thus representing the Semitic/Hebrew word meaning “princess.”

In the Hebrew language, a -y (י) ending can signify possession—“my [something].” Thus, a common interpretation of the original name of the matriarch, Sarai (שרי), is “my princess.” As such, a common explanation for the name change is that, in the context of Abraham becoming a father of many nations (verse 5), Sarai went from being Abram’s personal princess to simply being referred to more generically as “princess”—a princess not just of Abraham personally, but of many. As summarized by the following commentaries:

- Benson’s Commentary: “Sarai signifies my princess, as if her honour were confined to one family only; Sarah signifies a princess, namely, of multitudes.”

- Matthew Poole’s Commentary: “Sarai signifies my lady, or my princess, which confines her dominion to one family; but Sarah signifies either a lady or princess, simply and absolutely without restriction ….”

- Gill’s Exposition of the Entire Bible: “[H]er former name Sarai signifies ‘my princess’ … but Sarah signifies, as Jarchi observes, ‘princess’ absolutely, because she was princess over all the princes and people that should come of her ….”

- Pulpit Commentary: “[T]hou shalt not call her name Sarai, - ‘my princess’ … but Sarah ‘princess’ ….”

It’s a nice interpretation. Trouble is, it doesn’t quite make sense. Sarah as “princess,” yes—but not Sarai as “my princess.” In the words of the Cambridge Bible Commentary (emphasis added): “Sarah shall her name be - That is, Princess. … The name ‘Sarah’ is the feminine form of the Heb. Sar, ‘a prince.’ … ‘Sarai’ … cannot mean, as used to be asserted, ‘my princess.’”

Why not?

The Problem

The interpretation of Sarah is straightforward as the feminine of sar (“prince”), thus “princess.” Not only is the masculine form used throughout the Hebrew Bible, but the feminine form, princess or princesses, is used too (for example, in 1 Kings 11:3 and Isaiah 49:23).

But “my princess,” in Hebrew, would not be conjugated as Sarai/Sari (שרי). At face value, this would actually be how to say “my prince”—masculine. The word refers to “ownership” of a masculine “object.” A feminine word like Sarah, with a -h (ה) ending, would typically be conjugated differently. “Wife,” for example, is esha (אשה), with the same -h (ה) ending. “My wife” is conjugated as eshti (אשתי), the -h being replaced by a -ti (תי) ending (as in, for example, Isaac’s use of the term in Genesis 26:7). A similar form, in this case directly relating to the word “princess,” can be found in Lamentations 1:1: Sarati (שרתי, though there is some debate about the proper interpretation of this word in this context).

The interpretation of Sarai as “my princess,” therefore, doesn’t really make sense. As put by the McClintock and Strong Bible Commentary: “[T]he meaning of “Sarai” is still a subject of controversy. The older interpreters … suppose it to mean “my princess;” … [but] among modern Hebraists there is great diversity of interpretation.” The new name Sarah, however, as the feminine princess, does fit logically, and especially with her promised exalted royal role as a great matriarch highlighted in this chapter of Genesis.

So what does the former name Sarai really mean? Could it, like Abram’s name, be a link to a foreign place of origin?

Additional Details

Despite the Cambridge Bible’s dogmatic statement about the incorrect interpretation of the name Sarai as “my princess,” the commentary fails to go any further—and in the same (somewhat feeble) manner of other commentaries posing no real difference between the names Abram and Abraham, offers simply: “‘Sarai’ may possibly have been an older form of ‘Sarah.’” If that’s the case, it again begs the question, why bother with the name change at all?

But there are some interesting nuances contained within this biblical passage that highlight the difference between the two names, and suggest going deeper than simply concluding one as a sort-of “newer” form of the other.

Of note is a peculiar injunction in the name-change verse: God instructs Abraham, “thou shalt not call her name Sarai.” This is different wording to the Abram-to-Abraham name change, where the comment appears more passively, “Neither shall thy name any more be called Abram.”

You will no longer be called Abram, versus “thou shalt not call her name Sarai.” This is strong language—the same Hebrew negative imperative language found within the Ten Commandments, “thou shalt not,” as well as in the command to Adam and Eve not to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Genesis 2:17).

Whoa—why not? What’s wrong with “my princess” (if that was indeed the original meaning of the name)? Was God’s “thou shalt not” command here just a figure of speech, emphasizing Sarai’s new name as a simple replacement of the old? Or could there have been more to this original name?

But Is a Solution Even Possible?

For a name as short as Sarai/Sarah’s, it is far more difficult to arrive at a satisfying, absolute conclusion, as many options remain open based on such a small number of root letters. Various interpretations exist, including tying the name to the noun sharer (שרר, related to the absorption of liquid), sara (שרה, an unknown word related to Jacob’s wrestling match—Genesis 32:28, Hosea 12:3), shara (שרה, meaning to loosen), or perhaps even shor (שר, an umbilical cord). Note that such words with the same spellings in Hebrew can have different meanings, due to the context or added vowel markings.

Nevertheless, despite the level of ambiguity, we can submit a possible interpretation, and you—the reader—can pass judgment.

In our former article, we covered Abraham’s Amorite connection (not, of course, as a descendant of Ham—Genesis 10:15-16—but as falling under the wider territorial appellation at the time, and as a Semitic Babylonian “Amorite,” akin to the great second-millennium b.c.e. Babylonian king, Hammurabi). We noted Abraham’s own “Amorite Confederation” mentioned in Genesis 14:13, in the same chapter that describes Abraham’s interactions with Melchizedek in Jerusalem (then “Salem”), at which time the city was being founded—the very first chronological mention of it in the Bible. Genesis 22 proceeds to describe the (near-)sacrifice of Isaac in this Jerusalem location—setting the scene for the foundation of the site as the place of the temple and related sacrifices.

We also briefly reviewed Ezekiel 16:3—God’s poetic description of Jerusalem (King James Version): “Thus saith the Lord God unto Jerusalem; Thy birth and thy nativity is of the land of Canaan; thy father was an Amorite …”—a possible nod here, therefore, to Abraham? But notice further: “and thy mother a Hittite.”

The same refrain is repeated in verse 45: “[Y]our mother was a Hittite, and your father an Amorite.” If you’re like me, perhaps you’ve read right over these verses in the past. Numerous commentaries are confused by, and wrestle with, them. Matthew Poole’s Commentary at least hints at a possible association to Abraham within (but makes no mention of Sarah). Gill’s Exposition offers the following explanation: “thy father was an Amorite, and thy mother an Hittite; Abraham and Sarah, who were, properly speaking, the one the father, the other the mother, of the Jewish nation, were Chaldeans; and neither Amorites nor Hittites; yet, because they dwelt among them; are so called; and especially since before their conversion they were idolaters ….”

Is it possible? As with Abraham’s certain Amorite connections, could there be some form of Hittite connection to Sarai?

Mother of Jerusalem

It is interesting to compare this matrilineal Hittite-mother mention of Jerusalem in Ezekiel 16:3 with the above mentioned Lamentations 1:1. This passage poetically calls Jerusalem a sarah (or technically, in this conjugated case, sarah-ti)—calling Jerusalem a “princess among the provinces.” Could this, again, be more than a coincidental connection of Jerusalem to the same great mother and princess “Sarah,” wife of Abraham?

Another passage, suggesting an equivalence between Sarah and Jerusalem (and thus lending to this identification of Sarah as this mother referred to in Ezekiel 16:3), can be found in the New Testament—Galatians 4:26. This passage, while not mentioning Sarah directly, states that on the one hand, Abraham’s concubine “Hagar represents Mount Sinai in Arabia,” while on the other hand there is “Jerusalem.” Further, the “one from Mount Sinai which gives birth to bondage, which is Hagar” (verse 25), versus “Jerusalem which is above” (verse 27). Several commentaries therefore assert that while Mount Sinai here is typed by Hagar, Jerusalem is “fitly typified” by Sarah (Benson’s Commentary). The New Living Translation goes so far as to add Sarah’s name to the verse itself.

And in Isaiah 51, God speaks the following in the context of Zion (Jerusalem): “Look unto Abraham your father, And unto Sarah that bore you … For the Lord hath comforted Zion” (verses 2-3).

Thus, in identifying Sarai/Sarah as symbolic mother of Jerusalem—and in turn identifying her with this peculiar “Hittite mother” reference in Ezekiel 16:3—is there anything more that could hint toward a Hittite connection? There is another fascinating passage relating to Sarah.

‘In the Choicest of Our Sepulchres’

Genesis 23 describes the death of Sarah—and a fascinating land-purchase interlude, in which Abraham buries her on Hittite land within Canaan. “And Abraham rose up from before his dead, and said to the Hittites, ‘I am a stranger and a sojourner among you; give me property among you for a burying place, that I may bury my dead out of my sight.’ The Hittites answered Abraham, ‘Hear us, my lord; you are a mighty prince among us. Bury your dead in the choicest of our sepulchres; none of us will withhold from you his sepulchre …” (verses 3-6, Revised Standard Version). Such was the deference on the part of the Hittites, that they attempted to give away the burial ground free of charge (high-value property no less, valued at 400 shekels of silver).

Why did the Hittites so effusively praise Abraham? Why was any of their population willing to free up their sepulchers for Sarah? Was this deference to Abraham simply because his reputation preceded him? Certainly this must have been the case in large part. But was there also more to it? Why did Abraham specifically seek out this tract of land for burying his wife? Why did this territory come to be renamed Hebron, meaning “association,” “friendship” or “brotherhood”? And why was there such a bond of later Hittite allegiance to Israel—such as the infamous account of David’s soldier Uriah, husband of Bathsheba, who paid for his loyalty with his life?

Could it be possible that, as with Abraham and the Amorites, Sarah herself had some kind of original link to, or connection with, the Hittite realm, at least territorially and/or linguistically?

And could this be an avenue within which to look for an answer to the meaning of her former name?

Sarrai? Sarie?

The word sarrai is actually a known Hittite word, which means something like “separate.” This could conceivably be an answer.

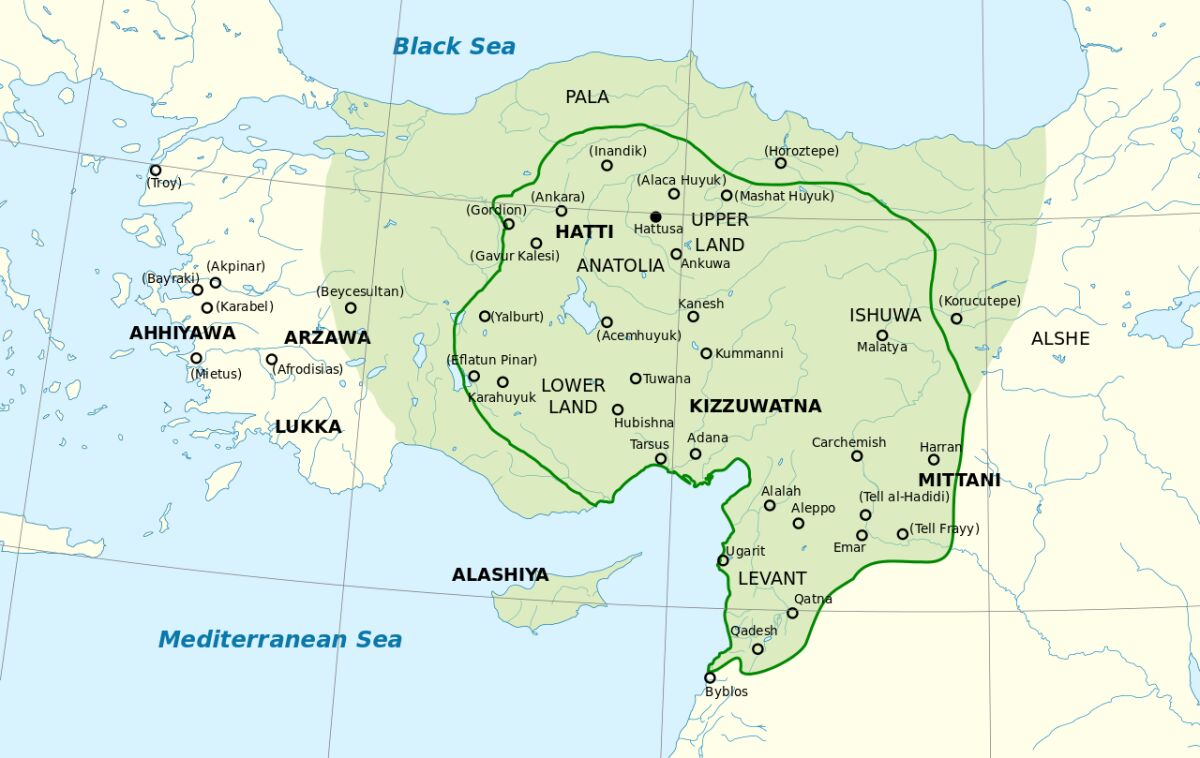

There is another interesting option. The late Hittitologist Volkert Haas, in his mammoth 1,000-page German-language book Geschicte der Hethitischen Religion (“History of the Hittite Religion,” 1994) noted a particular deity named Sarie worshiped within the city Apenaš, in Arrapha, modern-day northern Iraq (pg. 544). The location, Arrapha, is notable: It’s actually within certain territory directly related to one of the alternative geographic locations for Abram’s “Ur of the Chaldees.” (More can be read about this particular, northern Ur theory—a location more proximate to Hurrian/Hittite territory, and a theory held by such eminent ancient historians and scholars as Josephus and Maimonides—here.) Though Arrapha is technically within Hurrian territory (a territory neighboring that of the Hittites), the thorough interconnectedness of these two polities, right down to religion and mythology, has long been recognized. Much of what we know about the Hurrians comes from the Hittites, a civilization “greatly influenced” by them.

Is it beyond the realm of possibility that Sarah’s original name was derived from just such a place and/or form of deity? If so, perhaps she was not so different from the biblical Esther, whose name is commonly understood to be derived from the famous regional goddess Ishtar (with her uncle Mordecai’s name derived from the god Marduk)—or any biblical individual called out from within a pagan melee, for that matter. Naming individuals after deities was common practice in the pagan world (the story is the same in the New Testament, with Christian converts bearing names the likes of Apollos).

Though very little indeed is known about the deity, one strike against the identification would be that Sarie, from the very few extant inscriptions, appears to be a male god. (Still, it was not unusual for individuals to be associated with deities of the opposite gender—a case in point being the very father of Abarama, the individual highlighted in the earlier article on Abraham, who bore a name connected to the goddess Ishtar.)

One potential rebuttal for some form of Hittite connection could be Abraham and Sarah’s grandchild Esau taking Hittite wives in open resentment to his parents, which proved a “bitterness of spirit unto Isaac and to Rebekah” (Genesis 26:35). But this verse could be looked at in reverse logic. Why did Esau selectively go after Hittite women—and not only that, but also Ishmaelite women (Genesis 36:1-3), the latter clearly descended from Abraham’s union with Hagar? Was Esau, in his resentment toward his immediate patrilineal lineage, bypassing them by actively pursuing those somewhat more distant matrilineal familial connections that he, in his bitterness, felt he could better associate with?

It is worth noting that unlike Semitic Hebrew, the Hittite language is Indo-European (in the same family as Greek). Furthermore, it should be pointed out that the Hittites, as we commonly think of them, were not the original people to bear their national name. They displaced (or absorbed) a former Anatolian people, known as Hattians, but retained the same name—Hatti—for their territory. (This original Hattian population, who spoke a mysterious, non-Semitic and non-Indo-European language, are most likely the descendants of Heth mentioned in Genesis 10:15.) Indeed, at the time of Abraham, the king over this region, Tidal, was notably designated “king of nations” (Genesis 14:1)—highlighting the aggregate nature of his Anatolian kingdom at this point in time. (You can read more about this Genesis 14 account in our articles “Uncovering the Battle That Changed the World” and “Finding the Hittites.”)

Where Does That Leave Us?

When it comes to such a short, three-letter name as Sarai’s (שרי), it can be hard to get a fix on the accurate original meaning of the name—there is enough wiggle-room in ambiguity for endless theories, as described above, unless or until archaeological discovery brings further clarity to the matter. Some kind of Indo-European, Hittite linguistic or territorial connection is one option. You may have your own theories; it is interesting to speculate.

What is, at least, apparent is that Sarah’s original name, Sarai, appears to be a foreign name. As nice as the more common theory may sound—that the name is a transition from my princess to a more general princess (the oddness of the wording for making this interpretation work notwithstanding)—is there not a sense that there must be more to it to warrant the name change (and certainly if we are to take at face value such strong “thou shalt not” language)? Thus, could it be that Sarah’s initial name, Sarai, did not simply represent some form of an arbitrary word, but rather had some form of pagan, or at least negative, connotation?

A more foreign-sounding initial name—or even some form of a pagan name—would only fit the picture of Sarai, together with her similarly foreign-named husband Abram, with whom she was called out of, and was united in sojourning through, pagan foreign and faraway lands.

Thus, with the name-change of Genesis 17: At the same time that Abram became an “exalted father,” Abraham, through the promise of “many nations,” Sarai herself was similarly elevated—her former name reworked into the Semitic/Hebrew word “princess,” a royal title she was destined to fulfill over the multitude that would descend from her, as a royal “mother of nations.”

Article updated 18/12/23. See also: What Does the Name ‘Abraham’ Really Mean?