‘Thou Shalt Not Seethe a Kid in Its Mother’s Milk’: Peculiar Scripture Illuminated by Archaeology

“Thou shalt not seethe a kid in its mother’s milk.” It’s a thrice-repeated, enigmatic verse in the Torah, with no end of opinions and extrapolation. This is the cited source for the standard religious Jewish custom of not mixing meat and dairy in food products. (For unaware foreigners visiting Israel, this is often found out when you receive a burger without cheese at a restaurant!) Different groups adhere to different traditions surrounding the interpretation of this verse, in relation to the consumption of meat and dairy products. And as for the reason behind the command, You shall not cook a kid [a young male goat] in its mother’s milk? Again, there are various opinions.

Yet on that last point, there is something fascinating that can be said, based on a particular archaeological find—helping to illuminate the meaning of this enigmatic passage of Scripture.

‘Beyond Comprehension’

First, the Bible passages in question. There are three verses containing this statement:

- Exodus 23:19: “The choicest first-fruits of thy land thou shalt bring into the house of the Lord thy God. Thou shalt not seethe a kid in its mother’s milk.”

- Exodus 34:26: “The choicest first-fruits of thy land thou shalt bring unto the house of the Lord thy God. Thou shalt not seethe a kid in its mother’s milk.”

- Deuteronomy 14:21: “Ye shall not eat of any thing that dieth of itself; thou mayest give it unto the stranger that is within thy gates, that he may eat it; or thou mayest sell it unto a foreigner; for thou art a holy people unto the Lord thy God. Thou shalt not seethe a kid in its mother’s milk.”

Three specific passages of scripture, all affirming the same thing: “You shall not seethe a kid in its mother’s milk.” And so, one standard interpretation is that this command was meant to indicate that a meat item should not be cooked with or alongside a dairy item.

Again, what was the reason for God giving this law? There is plenty of speculation—including that it cannot be understood. Rabbi Aryeh Citron writes in an article titled “Meat and Milk”: “[I]t is clear that the main reason for this mitzvah [commandment] is beyond comprehension. Hence, it is referred to as a chok—a statute that we fulfill simply because it is the will of G-d, although we don’t understand it.”

This law, which is “beyond comprehension,” has been interpreted and extrapolated on through the centuries, with numerous guidelines for adherence to it added along the way. Citron lists some of them:

- “Torah Law only prohibits the consumption of meat that was cooked with milk. The rabbis added that one may not eat meat and milk together even if they were not cooked together. …

- In addition, the rabbis instituted that one must wait a certain amount of time between eating meat and milk.

- The rabbis also decreed that two acquaintances may not share a table if one is eating dairy products and the other is eating meat products.”

Regarding the instruction of waiting a certain amount of time between consuming meat and dairy, there are different traditions among different communities. Some prescribe waiting one hour, some three, and some as many as six hours after eating one substance before consuming the other. Citron continues:

The reason for waiting six hours is twofold. Firstly, because meat is fatty, the taste may linger in one’s mouth for a long time. With the passing of six hours, however, the taste dissipates. Secondly, if meat gets stuck between one’s teeth, it retains its halachic “meat” status for up to six hours. After six hours, it is no longer considered meat. (In practice, however, if one finds meat stuck between one’s teeth after six hours, one should remove it before eating dairy products.

In spite of the notion that this instruction is “beyond comprehension,” the famous 12th-century Jewish philosopher Maimonides (Rambam)—one of Judaism’s most highly regarded commentators—surmised the following reason: “As for the prohibition against eating meat in milk, it is in my opinion not improbable that … idolatry has something to do with it. Perhaps such food was eaten at one of the ceremonies of their cult or at one of their festivals … According to me this is the most probable view regarding the reason for this prohibition; but I have not seen this set down in any of the books of the Sabians that I have read” (Guide for the Perplexed, Part iii:48, Pines translation).

Nearly 800 years after his time, archaeological evidence did emerge showing just such a connection to “idolatrous festivals,” which Maimonides speculated about but was unable to find written evidence of.

Before we look at that, though, we need to take a step back and examine the context of the three passages in which this instruction is found.

‘Firstfruits of the Land’

There are two chapters in the Bible that primarily outline “clean” and “unclean” foods: Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14. The former passage makes no mention of this command. The latter chapter does contain it—but in a slightly unusual place, as we shall see.

Still, there is one thing that all three passages related to this instruction have in common: harvesting.

The first passage, Exodus 23:19, is preceded from verse 16 right into verse 19 by the topic of harvesting the firstfruits of the land. The second passage, Exodus 34:26, is likewise preceded by the same thing—verse 22 to verse 26 talks about harvest time for the firstfruits, with the command, You shall not seethe a kid in his mother’s milk tacked on at the end. Out of place? Hardly, as we shall see!

The third and final repetition of the command, in Deuteronomy 14:21, does follow after the stating of the laws of clean and unclean foods. You shall not seethe a kid in his mother’s milk is placed at the end of these laws, in verse 21. However, if you keep reading the very next words, you find the same theme as the first two passages above! Deuteronomy 14:22-23 discuss harvest time—reaping the firstfruits.

Thus, based on the precedent of the first two passages in Exodus, this Deuteronomy passage could best be fitted with the following verses about harvesting and firstfruits, rather than the preceding verses about clean and unclean meats. Support for this separation is further evident from the position of a summary statement to the clean and unclean laws in the same verse 21: “for thou art an holy people unto the Lord thy God.” This round-up statement comes just before the next sentence about seething a kid in his mother’s milk, which is followed by mention of the harvest. (Another related point for the command being best associated with the following verses about harvest time rather than the preceding verses about clean and unclean meats is the simple fact that the command is not found in the parallel Leviticus 11 passage on clean and unclean meats.)

Nevertheless, we see that in every case, the refrain You shall not seethe a kid in its mother’s milk is associated in context with the harvest. Another striking observation about this command is that nowhere does the biblical instruction directly say not to eat this substance. This is in contrast to the numerous statements in Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14 instructing people not to eat certain meats. Neither does this command specify young animals in general. When it comes to this command in the Torah, we are literally only instructed not to seethe, or cook, a young male goat in the milk of its mother. And then, for whatever reason, the harvest is mentioned.

‘Magic’ of the Heathen

Again, from Rambam: “[I]t is in my opinion not improbable that … idolatry has something to do with it. Perhaps such food was eaten at one of the ceremonies of their cult or at one of their festivals.”

When examining these passages of the Torah, it is important to remember that Israel, at this time, had been only recently freed from slavery and a saturation in pagan customs (an explanation for many of the Torah laws so peculiar to us today). Idolatry was something that God was attempting to root out of the national psyche as He led them on their exodus through the wilderness.

Originally published in 1706, Matthew Henry’s Commentary explained the instruction this way:

At the feast of ingathering, as it is called (v. 16), they [Israel] must give God thanks for the harvest-mercies they had received, and must depend upon him for the next harvest, and must not think to receive benefit by that superstitious usage of some of the Gentiles, who, it is said, at the end of their harvest, seethed a kid in its dam’s [mother’s] milk, and sprinkled that milk-pottage, in a magical way, upon their gardens and fields, to make them more fruitful next year. But Israel must abhor such foolish customs” (Volume i, Genesis to Deuteronomy).

Later that same century, John Gill’s Exposition of the Entire Bible offered the following:

Maimonides and Abarbinel both suppose it was an idolatrous rite, but are not able to produce an instance of it out of any writer of theirs or others: but Dr. Cudworth has produced a passage out of a Karaite author, who affirms, “it was a custom of the Heathens at the ingathering of their fruits to take a kid and seethe it in the milk of the dam, and then, in a magical way, go about and besprinkle all their trees, fields, gardens, and orchards, thinking by this means they should make them fructify, and bring forth fruit again more abundantly the next year.”

These assessments from various sources fit tidily with the biblical harvesting context of the command, You shall not seethe a kid in its mother’s milk. And then, some two centuries later—in 1930—a parallel discovery was made in northern Syria.

KTU 1.23

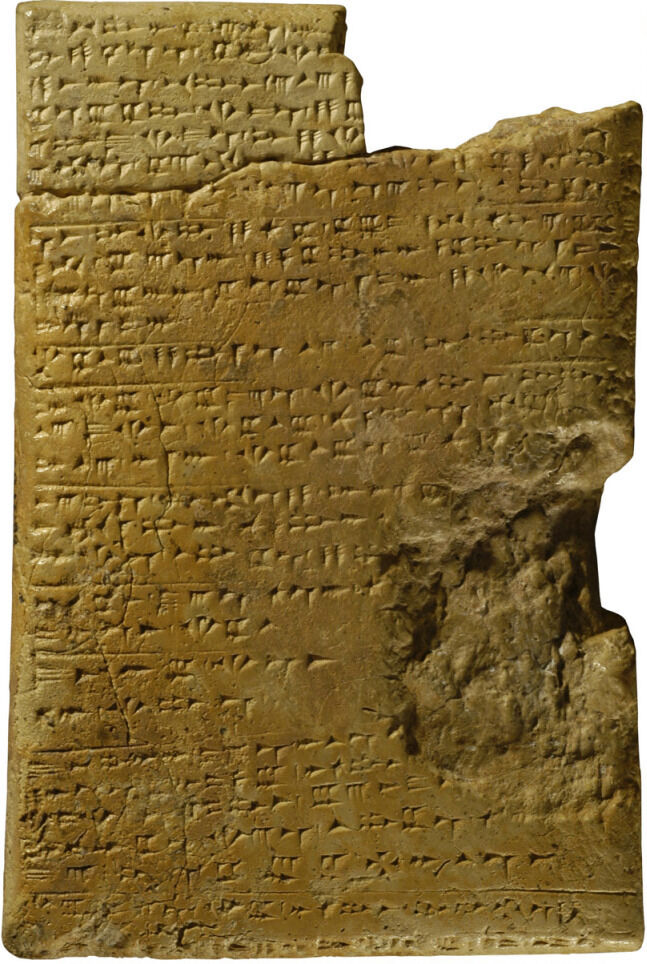

A cuneiform tablet known as “KTU 1.23” was discovered during the excavations of Claude Schaeffer in the acropolis of Ras Shamra (Ugarit), in a building known as the “great priest’s house.” The text was translated by French archaeologist Charles Virolleaud, titled “La Naissancedes Dieux Gracieux et Beaux” (“The Birth of the Graceful and Beautiful Gods,” alternatively titled more simply, “Birth of the Gods”). The tablet, dating to the 14th century b.c.e. (and therefore fitting with the general timeframe of the Exodus, alongside numerous other textual parallels for this date), contained 76 lines of rather hedonistic text relating to a fertility ritual.

The text describes the god Il’s sexual relations with his two wives. As described by Stanislav Segert in “An Ugaritic Text Related to the Fertility Cult (KTU 1. 23)”:

The use of sacred marriage in fertility rites is based on imitative magic: human fertility may assure fertility of animals and plants. Some relics of sacred marriage rites survived until recent times in agricultural rites performed in the Ukraine, Germany and Lithuania. … If the [KTU 1.23] narrative had to serve as model for a rite, two women and one man were expected to participate in it.”

Several scriptures throughout the Torah warn against the Israelites adopting such “magical” imitative practices of the inhabitants of Canaan.

Probably the most discussed part of this inscription, however, is line 14. In the context of some kind of ritual relating to “the field, the field of the gods, the field of Athrt and Rhm,” is the following, partly damaged instruction (as it is generally translated): “Cook a kid in milk, a [?] in curds.”

Cook a kid, or young male goat, in milk? (Ugaritic gd bhlb, nearly identical to the biblical Hebrew used in these verses, gdy bhlb.) This text, then, sheds light on this peculiar biblical instruction always connected to harvesting, fields, or their fertility. In light of the discovery, Peake’s Commentary (published 1962) relayed the following explanation for Exodus 23:19, Exodus 34:26 and Deuteronomy 14:21: “The significance of this prohibition [in these three biblical verses] has now been made clear by the Ras Shamra texts. According to the Birth of the Gods, i, 14, a kid was cooked in its mother’s milk to procure the fertility of the fields, which were sprinkled with the substance which resulted.”

This discovery, as well as the implications for understanding the biblical command, is interesting for several reasons. Israel, a new nation emerging out of Egypt, was at that point in many ways a paganized people (nothing speaks to this more than the incident of the golden calf). Numerous biblical passages in the Torah highlight Egyptian worship practices that the Israelites would have been familiar with, which were to be “unlearned.” But Israel was also now moving into the land of Canaan, into a melee of other pagan practices extant in the Levant—practices that would potentially be witnessed by the Israelites and were to be avoided. This fertility practice of cooking a male goat in milk, attested to on the above-mentioned Levantine Ugarit inscription (and within the same ballpark timeframe of the Exodus) would have therefore been one of the practices the Israelites were likely to encounter.

And so, in educating His new nation, in the context of harvest time, God commanded the Israelites not to follow these same “magical” practices of the heathen in an attempt to incur some kind of a fertility blessing. Instead, Israel was to look to God as provider and rely on Him for the health and benefit of future harvests (or it could be said more broadly, through the spirit of the command, any venture or undertaking). Israel was to look to God, rather than to a pagan goat-and-milk custom, for His blessing!