The Book of Judges Fails to Mention an Egyptian Presence in Canaan—Or Does It?

“Canaan was absolutely dominated by New Kingdom Egypt from the conquest of Thutmose iii all the way through until the end of the Ramesside period,” stated Dr. Chris McKinny in a 2022 On Script: Biblical World podcast titled “Early or Late Emergence of Israel,” speaking of the geopolitical situation in Canaan throughout much of the second half of the second millennium b.c.e. “And so, not only do you have a problem internally, of the Exodus story and how that works, but once Israel finally emerges and comes into the land of Canaan, they’re coming into a landscape which would be [the time of] Joshua and Judges, that is absolutely controlled by a whole host of important pharaohs …. There’s no reference to this [Egyptian control] in Joshua or Judges, and it seems to fit, in my opinion, much better towards the end of the New Kingdom’s control, when Egyptian power is weakening in Canaan.”

McKinny—a proponent of a late-date emergence of ancient Israel—believes the data best fits with an Israelite emergence on the other side of this Egyptian dominion, toward the latter end of the second millennium b.c.e.

Prof. Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman articulate similar thoughts about the Egyptian presence in Canaan in their infamous 2001 work, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts: Late second millennium b.c.e. Canaan “was an Egyptian province, closely controlled by Egyptian administration. The provincial capital was located in Gaza, but Egyptian garrisons were stationed at key sites throughout the country, like Beth-shean south of the Sea of Galilee and at the port of Jaffa (today part of the city of Tel Aviv). In the Bible, no Egyptians are reported outside the borders of Egypt and none are mentioned in any of the battles within Canaan.”

In a 2021 Albright Institute interview, “The Rise of Ancient Israel in the Highlands,” Finkelstein asserted the same belief: “The Bible, in my opinion, does not have any recollection of the situation in the Bronze Age. It is very easy to prove that the Bible has no recollection of crisis at the end of the Bronze Age, no memory of the end of the Egyptian system, no memory of Egypt in Canaan” (emphasis added throughout).

Is it true? And how can this be reconciled—if at all—with the biblical account of the Exodus and conquest of Canaan?

Argument From Silence?

If you do a word search for “Egypt,” or derivatives thereof, in the Bible (in English or in Hebrew), you’ll find that the only mention of the place—or its people—in Joshua and Judges is in the context of referring to the Exodus. There is no explicit mention of Israelites interacting with “Egyptians”—in the strict use of the word—in Canaan.

Yet archaeologically, we know of a number of Egyptian-controlled strongholds throughout Canaan. The 15th-century b.c.e. pharaoh Thutmose iii campaigned heavily in the Holy Land, carving out for himself an expansive empire; his son, Amenhotep ii, likewise campaigned in Canaan during the early part of his reign. The 14th-century b.c.e. pharaoh Akhenaten received numerous messages from his proxies in Canaan (the Amarna Letters). The famous 13th-century b.c.e. pharaoh Ramesses ii, who campaigned into Canaan, reasserted Egyptian control over the area during his reign, with strongholds functioning throughout his reign and the reign of the subsequent Ramesside pharaohs (more on this further down).

Yet taking biblical chronology at face value (as expressed in passages such as Judges 11:26 and 1 Kings 6:1), this would be well within the period of the judges. If the Egyptians had such a heavy hand in the southern Levant, why is there no mention of them?

A relatively common response to this argument is that for the biblical judges epoch, there are several periods for which oppressors are named, but there are also several cases in which they are not. Take, for example, the judge “Tola the son of Puah,” who “arose to save Israel” from an unnamed enemy, “[a]nd he judged Israel twenty and three years” (Judges 10:1-2).

But what if there was a particular passage in the book of Judges that actually refers to this Egyptian presence in the land?

Avenging, Leading, Freeing, Growing Hair—What?

Judges 5 is often called the “Song of Deborah.” A hymn of jubilation following the defeat of Jabin’s captain Sisera and his chariot army, it describes the mournful state of the land to that point in time—the severe fragmentation of the Israelite tribes (verses 14-18); the fear of traveling highways (verse 6); the veritable “captivity” of the Israelites within the land in which they lived (verse 12). This takes place some significant length of time into the judges period; it is after the 48-year interlude of Cushan-Rishathaim’s opression and Othniel’s judgeship (Judges 3:8, 11); the 98-year interlude of Eglon’s oppression followed by Ehud’s judgeship (Judges 3:14, 30); and the 20 years of Jabin’s oppression (Judges 4:3).

The very start of the prophetess Deborah’s song has long confused translators: “Praise ye the Lord for the avenging of Israel, when the people willingly offered themselves” (Judges 5:2, King James Version). These italicized words are the lead words of this verse in the original Hebrew. Yet the way they are handled by various translations is wildly different. Consider the Jewish Publication Society’s translation: “When men let grow their hair in Israel, When the people offer themselves willingly, Bless ye the Lord.” The New King James Version reads: “When leaders lead”; Young’s Literal Translation, “For freeing freemen.” Others simply avoid this part of the verse altogether and jump straight to: “O you of Israel, that have willingly offered your lives to danger, bless the Lord” (Douay-Rheims).

At the core of this problem are two words in Hebrew (that are in fact a play on one another, given their core consonants): בפרע פרעות. For Hebrew readers, the second word, פרעות, is particularly striking because it happens to be precisely the plural of the Hebrew word pharaoh (פרעה).

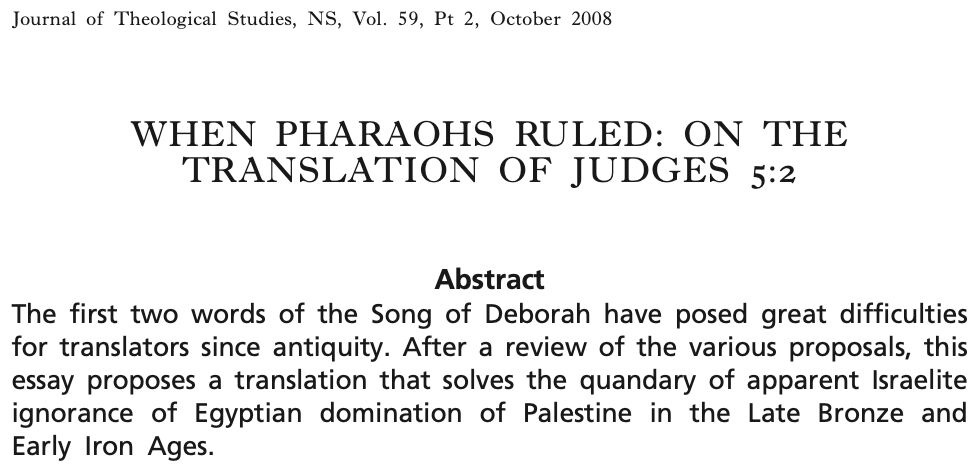

When I first stumbled upon this (doing a Bible word-search for the Hebrew word “pharaoh”), I was stunned. Only more so when I discovered a 2008 article on this very subject written by the late Dr. Robert D. Miller ii, titled “When Pharaohs Ruled: On the Translation of Judges 5:2.”

“The first two words of the Song of Deborah have posed great difficulties for translators since antiquity,” he wrote. “After a review of the various proposals, this essay proposes a translation that solves the quandary of apparent Israelite ignorance of Egyptian domination of Palestine in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages.”

When the Pharaohs Ruled

“[A]fter the Exodus, the Bible does not mention Egypt again as a nation until the story of Saul,” Miller wrote, highlighting the conundrum of an Egyptian presence in Canaan, against the apparent lack of biblical mention thereof.

Yet Papyrus Anastasi 3 shows that during the reign of Ramesses iii (until 1155 b.c.e.), Egypt held a powerful grip on parts of Palestine …. Palestine supplied Egypt with grain, wine, oil, slaves and horses. Even in the highlands, Egyptian power did not collapse until the end of the reign of Ramesses iii and possibly not until the end of Ramesses iv (1149 b.c.e). Ramesses iv seems to have held power of some sort in Galilee, the Jezreel Valley, Judah and along the coast. Canaanites bring tribute to Ramesses v (1149–1145 b.c.e). Egyptian material continues to be found archaeologically in the Jezreel Valley, at Hazor, in Judah, the Negev, and along the coast even from the reign of Ramesses vi (1145–1137 b.c.e). There was, therefore, a clearly targeted Egyptian administrative and military presence well into the 12th century. Does the Bible’s failure to recognize any Egyptian influence in Canaan in the books of Joshua and Judges reflect a total lack of knowledge of the real situation …?

Miller doesn’t think so, “propos[ing] that there is a biblical reference to Egyptian rule in Canaan in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages. The reference is found in the opening lines of the Song of Deborah.”

He highlighted these two opening words of the song, בפרע פרעות, as the “colophon or ‘byline’ of the song.” Miller reviewed the various attempts in both early and later sources to translate this passage, pointing out various improbabilities and impossibilities in such attempts. In spite of all such attempts at translation, “[t]he meaning of these words is actually quite clear. The second word is obviously the plural of ‘pharaoh’ ….”

Miller explained the construct of the word. Further, given the initial word—פרע (the first letter ב is a prefix)—is related, it is clear that there is word-play going on here. He continued:

The Hebrew writers wished to coin a phrase: “When the Pharaohs pharaohed.” Namely, they wanted to coin a verb that would cover the action done by a pharaoh and express the combination as a cognate accusative. Compare Numbers 11:4 [“lusters lusting”]; Isaiah 35:2 [“blossoms blossoming”]; Psalm 14:5 [“fearful fearing”], where the accusative noun is likewise anarthrous …. This would best be rendered in English as “When Pharaohs ruled.” …

[This] fits the function of the superscription better than any of the other proposals; it actually provides a date formula that situates the events of the song.

Many translations do give a sense of this, in translating the passage to read, “When the leaders led.” Yet they overlook the precise type of leader spelled out in the Hebrew text—pharaohs. It is understandable why this may not have made sense to early translators for a setting within the judges period—but in hindsight, against the backdrop of archaeological discovery, the use of this term makes perfect sense. “[W]e have in this ancient song a vague memory of the days ‘when Pharaohs ruled’” in Canaan, Miller concluded.

Other Egyptian Links

Judges 5:2 isn’t the only link to the reality of some kind of Egyptian presence in judges-period Canaan (though it is perhaps the most explicit). There are other clues within the text.

One is the military captain Sisera (Hebrew, Ses-Ra), described in Judges 4-5. This individual has long been suggested as having been an Egyptian mercenary captain, with a name possibly meaning “Servant of Ra”—Ra, not only referring to the chief Egyptian deity but also the name of one of the four chariot divisions of the Egyptian army at the Battle of Kadesh (circa 1274 b.c.e.). Recall that Sisera was a captain over an extraordinarily large army of 900 chariots (Judges 4:13).

This links further with the geopolitical situation at this time. Ordinarily, such a large chariot force as accounted in the Bible would be scoffed at. Yet this Battle of Kadesh—duked out between the Egyptians and the Hittites at the modern-day border of Lebanon and Syria—happens to be famously known as the largest chariot battle ever fought, with the Egyptians wielding a force of around 2,000 chariots against a Hittite chariot force estimated (rather more wildly) at anywhere between 2,500 to 10,500. This would have resulted in an incredible flush of chariots into the Levant—a massive chariot presence which just so happens to be represented in this particular biblical account (in my opinion, set in the decades following the Battle of Kadesh, probably toward the end of the 13th century b.c.e.—see here for more detail).

Again, to quote Finkelstein: Does the Bible really have no memory of the Egyptians in judges-period Canaan? Judges 5:2—in its plainest, most straightforward reading—answers that it does. Certain other clues such as Sisera and his chariot-army lead to this conclusion as well.

But we have two questions here: Not just whether or not an Egyptian presence at certain times in Canaan is attested to in the Bible—but also how this relates to the period of the Exodus and the timeframe of Joshua’s conquest. And here, Finkelstein and Silberman bring up a good point in their aforementioned book.

Where’s the Room for the Conquest?

“[I]ndications—both literary and archaeological—seem to show that in the 13th century b.c.e., the grip of Egypt on Canaan was stronger than ever,” write Finkelstein and Silberman, demonstrating the impossibility of a biblical conquest occurring within this timeframe (op cit).

Archaeology has uncovered dramatic evidence of the extent of Egyptian presence in Canaan itself. An Egyptian stronghold was excavated at the site of Beth-shean to the south of the Sea of Galilee in the 1920s. Its various structures and courtyards contained statues and inscribed hieroglyphic monuments from the days of the pharaohs Seti i (1294–1279 b.c.e.), Ramesses ii (1279–1213 b.c.e.), and Ramesses iii (1184–1153 b.c.e.). The ancient Canaanite city of Megiddo disclosed evidence for strong Egyptian influence as late as the days of Ramesses vi, who ruled toward the end of the 12th century b.c.e. This was long after the supposed conquest of Canaan by the Israelites.

It is highly unlikely that the Egyptian garrisons throughout the country would have remained on the sidelines as a group of refugees (from Egypt) wreaked havoc throughout the province of Canaan. And it is inconceivable that the destruction of so many loyal vassal cities by the invader would have left absolutely no trace in the extensive records of the Egyptian empire. The only independent mention of the name Israel in this period—the victory stele of Merneptah—announces only that this otherwise obscure people, living in Canaan, had suffered a crushing defeat. Something clearly doesn’t add up ….

Despite certain late-date proponents arguing for a later emergence of Israel based on this presence of Egypt in Canaan, as highlighted by Finkelstein and Silberman, the comparatively popular 13th-century b.c.e./19th Dynasty position would put Joshua’s conquest and Israel’s emergence right at the height of Egyptian control within the land. This creates an unrealistic—one might say absurd—scenario, in which Joshua and the Israelites are not wresting land from the Canaanites, but from Egyptians at the height of their power.

Archaeologist Dr. Nava Panitz-Cohen describes this scene of 19th Dynasty Egyptian hegemony in Canaan, in her chapter in the 2014 Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant, c. 8000–332 B.C.E.:

The end of the Amarna interlude [mid-late 14th century b.c.e.] was followed by a much tightened control of Canaan by the rulers of the 19th Dynasty, covering all of the 13th century b.c.e. This phase ([Late Bronze Age] LB iib) began with the military campaigns of Seti i (1295 b.c.e.) and was dominated by the long-lived Ramesses ii (1279–1212 b.c.e.). …

The reign of the 19th Dynasty marked an unprecedented intensification of Egyptian presence in Canaan, well-attested in Egyptian sources by a step-up in punitive military campaigns, and in the archaeological record by the governors’ residencies and garrison stations established at strategic locations (i.e. Deir el-Balah, Beth Shean, Jaffa, Gaza, Tel Mor, Lachish, Aphek, Tel Sher’a, and possibly Gezer and Megiddo), temples dedicated to Egyptian deities, and an increase in Egyptian and Egyptianized objects, inscriptions, and burial customs …. (“The Southern Levant [Cisjordan] During the Late Bronze Age”)

Egyptologist Daphna Ben-Tor concurs in her contribution to the 2011 publication Egypt, Canaan and Israel: History, Imperialism, Ideology and Literature, writing:

The corpus of 18th Dynasty scarabs found in Palestine is much smaller than that of the Middle Bronze Age but the 19th Dynasty saw a significant increase in the number of imported scarabs, especially during the reign of Ramesses ii. Considering the archaeological evidence, it is reasonable to assume that this increase in the number of scarabs reflected the intensified Egyptian presence in Palestine in the face of the growing power of the Hittite empire in the north. The material culture of southern Canaan underwent a conspicuous Egyptianization in the Ramesside Period, and Egyptian influence increased significantly in comparison with the 18th Dynasty. (“Egyptian-Canaanite Relations in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages as Reflected by Scarabs”)

Finally, Marc Van De Mieroop writes in his 2010 book A History of Ancient Egypt:

Egypt’s administration of its Syro-Palestinian territories had been relatively loose during the 18th dynasty. Local vassals were responsible for carrying out imperial orders and only a few Egyptian administrators were involved. After the conquest phase Egyptian military presence was also limited. That system ended in the Ramessid Period. Instead the Egyptians intensified their presence in the region, building officials’ residences and military garrisons, and transforming strategically located towns into fortresses. The amount of Egyptian remains increased dramatically, with more architecture, including temples to Egyptian deities, royal and private statuary, steles, inscriptions, and pottery. It also seems that local people accepted Egyptian cultural influence more readily and in archaeological remains the local traditions grow fainter. The strengthened presence suggests that the Egyptians annexed the region and occupied it militarily.

This situation fits remarkably well with the assessment of the prophetess Deborah—a time “when the pharaohs ruled,” a time in which the tribes were fractured and strategic highways were unused by cowed locals—not a situation resemblant of the Israelite Exodus and conquest—a scenario which almost seems comical in light of God’s reassuring in Exodus 14:13 following the Red Sea incident that these Israelites would not reencounter the Egyptian forces. On a late-date, 13th-century model, the Israelites would run into them almost immediately!

Options of Reconciliation

These quotes from Panitz-Cohen, Ben-Tor and Van De Mieroop were highlighted by Dr. Joshua Bowen in a February 28 Rationality Rules podcast with Dr. Kipp Davis and Stephen Woodford, responding to the claims of 13th-century b.c.e. Exodus/conquest proponents and apologists Dr. David Falk and Michael Jones. In highlighting the veritable impossibility of the 13th-century position, Dr. Davis offered an alternative solution to Falk and Jones:

Rutgers professor Gary Rendsburg has opted for a 12th-century Exodus, precisely because of ongoing Egyptian control all the way into the 20th Dynasty. … Amihai Mazar, whom Josh and I had the pleasure to interview a couple of months ago, has characterized the Egyptian presence in Canaan as domination. Domination! during the 19th and the 20th Dynasties. Albeit, considerably weakened after the reign of Merneptah. …

Falk’s attempt to downplay Egyptian control in Canaan during the reign of Ramesses ii is just not clearly reflected in the sources, nor in the material culture. It’s telling—they have to do this—you have to downplay the Egyptian presence in Canaan in order to make any sort of conquest model work. Unless you’re going to dramatically shift the date of that ….

I would agree entirely that the only solution is to “dramatically shift” the date of the Exodus and conquest model. Not, however, forward (something that comes with its own host of internal and external issues), but rather, backward to the prescribed timestamps found within the biblical account itself: an Exodus 480 years prior to the construction of Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 6:1); a conquest 300 years prior to the tenure of the judge Jephthah (Judges 11:26); a 19th generation prior to the time of David (1 Chronicles 6); a conquest occurring during the prior 18th Dynasty—precisely that dynasty in which Egyptian influence in Canaan was “relatively loose” (Van De Mieroop) and the corpus of administrative remains “much smaller” (Ben-Tor). A specific century-long period within this dynasty for which there was a peculiar and notable lack of campaigns and intervention by Egyptian pharaohs—all the way from the end of the 15th century b.c.e. to the end of the 14th century b.c.e., a period for which we do actually have attestation for Canaan being overrun by marauding forces—the “Habiru”—as reported in desperate correspondence from Canaanite governors to the pharaoh of Egypt, begging for help. (Read “The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?” for more on this subject.)

Only after this—from the end of the 14th through the first half of the 12th centuries b.c.e.—did the Egyptians reassert their presence in the beleaguered and fragmented judges-period land, with a series of campaigns and the establishment of a string of military outposts and waystations, a time in which “southern Canaan underwent a conspicuous Egyptianization in the Ramesside Period, and Egyptian influence increased significantly in comparison with the 18th Dynasty” (Ben-Tor).

This reality, I believe, is aptly and explicitly accounted in the book of Judges itself, roughly halfway through this almost anarchical biblical period—a time in which “the pharaohs ruled.”