Manetho’s Exodus Pharaoh, ‘Amenophis’ (Amenhotep): Any Reason to Doubt?

In the debate about the dating of the Exodus, we have covered in some detail the case for the early date (within the 15th century b.c.e.), as opposed to the comparatively popular late date (within the 13th century b.c.e.). Key scriptural passages include the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1, the 19 generations of 1 Chronicles 6, the 300 years of Judges 11:26, particulars surrounding Exodus 1:11 (in light of Genesis 47:11 and Exodus 2:23), and various other pieces of internal biblical evidence.

In placing the Exodus within this earlier 18th Dynasty of Egypt (the great dynasty of the Thutmoses and Amenhoteps, spanning the mid-16th through 14th century b.c.e.) as opposed to within the later 19th Dynasty of Egypt (the 13th-to-12th-century b.c.e. Ramesside dynasty), one of the key extrabiblical pieces of evidence is the testimony of Manetho.

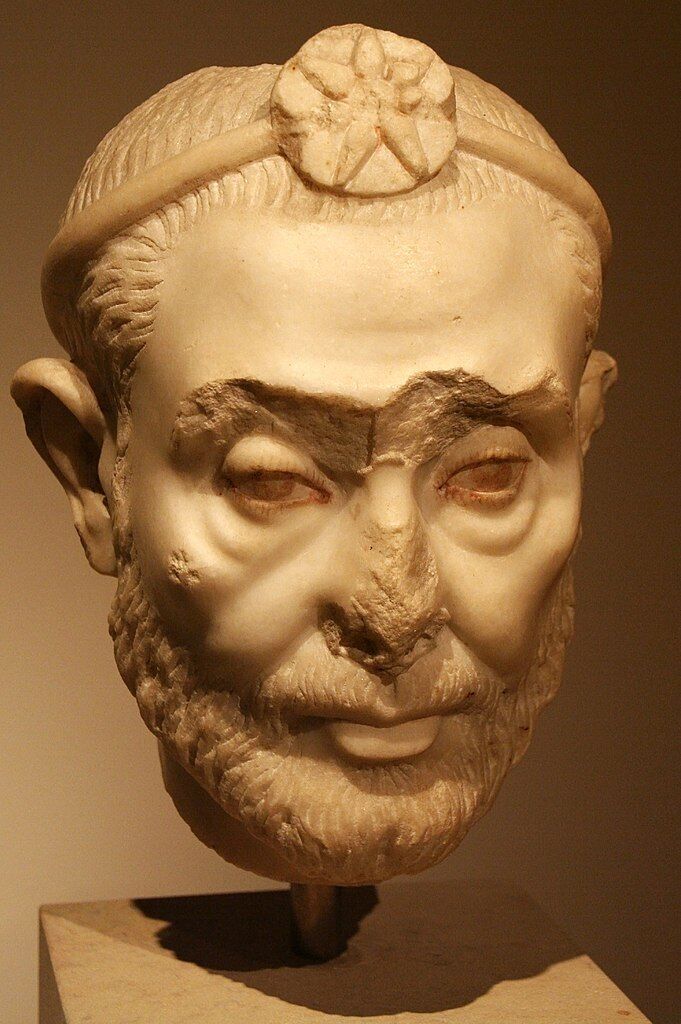

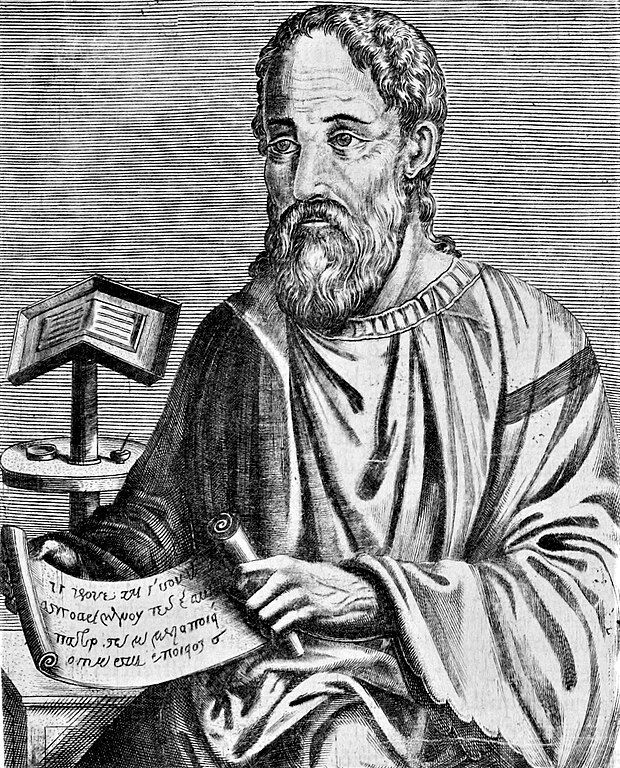

Manetho was a Ptolemaic Egyptian historian and Serapis-cult priest on the scene during the early third century b.c.e., who is known for compiling a detailed history of Egypt called Aegyptiaca. Unfortunately, the work has largely been lost to history. Only fragments of Manetho’s writings survive, as quoted from in later texts—most notably contained in the writings of the first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus in Book 1 of Against Apion.

Josephus’s lengthy quotations of Manetho reveal the pharaoh at the time of Moses and the Exodus to have been a certain “Amenophis”—a Greek variant of the name Amenhotep. This, then, is held up by early-date proponents as extrabiblical proof of the early Exodus, during the reign of one of the four 18th Dynasty pharaohs named Amenhotep (usually the 15th century b.c.e. pharaoh Amenhotep ii). Manetho’s identification is especially significant in that it not only comes from an outside, non-biblical source, but it is the earliest-known reference directly naming the Exodus pharaoh. It also comes from an Egyptian source and a priest who would have had greater access to sources of his nation’s history.

Naturally, there is pushback to such citations of Manetho from late-date, Ramesside Exodus proponents. Do the counterarguments undermine this identification of the Exodus pharaoh?

Four Different Versions—Which One?

A case in point was highlighted in a 2022 YouTube debate between early-date, 15th-century b.c.e. Exodus proponent Dr. Titus Kennedy and late-date, 13th-century b.c.e. proponent Dr. David Falk. Both are staunch defenders of their respective positions on the dating of the Exodus. Naturally, Dr. Kennedy cited Manetho among his proofs.

Dr. Falk responded in kind:

Josephus’s version [of Manetho] names Amenhotep ii. And I’ll give you that one’s Amenhotep ii. But then we’ve got Eusebius’s version that claims Akhenaten as king of the Exodus. You’ve got Africanus’s version that lists Ahmose i as king of the Exodus. And then you have Theophilus’s version of Manetho that names Thutmose iv as king of the Exodus. Four different versions—which one’s the correct one?

Well, given that Manetho is a third-century b.c.e. Egyptian priest, chances are that none of them are the original—that this Ptolemaic priest wouldn’t have cared and this is the editorial glossing of later Christian and Jewish writers. And this is just basic lower text criticism here. This is nothing extraordinary.

It’s an interesting objection. Can we really not know or trust any of the extant quotations of Manetho’s writings in relaying the name of the Exodus pharaoh?

Let it be said from the outset that while considering Manetho’s naming of the Exodus pharaoh to be valuable, I consider it to be a lower-tier piece of evidence—hence concluding with it in my article on the subject, “Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?” (rather than leading out with it, as in the case of certain other proponents). Nonetheless, the above dismissal of Manetho’s Exodus pharaoh strikes as disingenuous. Here’s why.

What About Eusebius, Africanus and Theophilus?

The four alleged versions of Manetho are as follows:

- The first-century c.e. historian Josephus relays an “Amenophis” as Exodus pharaoh (Amenhotep; preferring the 15th-century b.c.e. Amenhotep ii).

- The late second-century c.e. bishop Theophilus relays a “Tethmosis” as Exodus pharaoh (Thutmose; identifying him as Thutmose iv, as Falk does, would put him in the late 15th to early 14th century b.c.e., depending on the chronology).

- The late second/early third-century c.e. historian Sextus Julius Africanus relays an “Amos” as Exodus pharaoh (Ahmose; specifically, Ahmose i, 16th century b.c.e.).

- The late third/early fourth-century c.e. historian Eusebius relays an “Achencheres” as Exodus pharaoh (Akhenaten, 14th century b.c.e.).

A collection of these excerpts can be found here. Interestingly, all of these are 18th Dynasty pharaohs anyway; therefore, they all point to the same, early period of the Exodus. Still, is it really true that there is such a grab bag of names attributed to Manetho for his Exodus pharaoh? Is the identity of Manetho’s Exodus pharaoh really so doubtful?

First Up: Theophilus

In form, these citations of Manetho come to us in two different ways. Josephus is unique in that his text consists of lengthy block quotations of Manetho in narrative form, in addition to a simplified list of pharaohs. The three other sources simply transmit a listing of Manetho’s pharaohs of Egypt. As such, these are generally seen as quoting from two Manethoan sources: the first, as material derived from a detailed Manethoan storyline of Egyptian history (from which Josephus draws his material); the second, as simple list-form summaries of the pharaohs of Egypt.

These four sources containing these two different forms of information can be divided further. The second-century Theophilus’s account is actually seen as “obviously derived wholly from Josephus, any variations from the text of Josephus being merely corruptions” (Manetho: History of Egypt and Other Works; emphasis added throughout). Theophilus’s account does parallel well the information found within Josephus.

But what about Theophilus’s “Tethmosis” (Thutmose)? Actually, the naming of this individual as pharaoh of the Exodus is decidedly not in quoting Manetho; it’s contained in a preamble by Theophilus:

Moses was the leader of the Jews, as I have already said, when they had been expelled from Egypt by King Pharaoh whose name was Tethmosis. After the expulsion of the people, this king, it is said, reigned for 25 years, four months, according to Manetho’s reckoning. (Ad Autolycum 3.19)

Theophilus then proceeds to give a simple listing of the Egyptian rulers, as derived from Manetho.

That the above is not a direct quote from Manetho should be obvious (especially given his referencing Manetho in the third person) and that Theophilus is following Josephus should also be obvious. Why? Because Josephus himself argues that the Exodus pharaoh was Tethmosis—and in quoting Manetho’s repeated references to “Amenophis,” Josephus actually disputes this Egyptian priest’s identification, attempting to make a case for this earlier pharaoh “Tethmosis” in Manetho’s list.

Theophilus’s “Tethmosis,” then, is incontrovertibly not a quote from a different version of Manetho naming a different pharaoh of the Exodus.

What About Africanus?

Rather than the lengthy Manethoan narrative quotations of Josephus, the fragments relayed by Africanus and Eusebius are simple king-lists, providing successive pharaohs and regnal lengths for the 18th Dynasty. For certain individuals in these lists, different “notes” are inserted, giving additional information about certain of the rulers.

These lists given by Africanus and Eusebius actually come to us in particular through the writings of an eighth-century c.e. Byzantine chronicler, George Syncellus. As relayed through Syncellus, Africanus’s list is much like Theophilus’s and begins with a preamble:

The 18th Dynasty consisted of 16 kings of Diospolis.

The first of these was Amos, in whose reign Moses went forth from Egypt, as I here declare; but according to the convincing evidence of the present calculation it follows that in this reign Moses was still young. (Manetho: History of Egypt and Other Works)

Syncellus then proceeds to quote Africanus in following the list of Manetho, containing successive rulers and regnal lengths:

The second king of the 18th Dynasty, according to Africanus, was Chebros, who reigned for 13 years.

The third king, Amenophthis, reigned for 24 (21) years.

The fourth king (queen), Amensis (Amersis), reigned for 22 years. …

Does the preamble to this information represent a “quotation” of Manetho identifying the Exodus pharaoh as “Amos” (Ahmose i)? Not by any stretch of the imagination. The language of the paragraph makes this abundantly clear. The footnotes in Loeb’s Manetho: History of Egypt and Other Works specify further, that “as I here declare” is a quotation of Africanus’s personal opinion as to the Exodus pharaoh being this particular Ahmose; and the “but according to the convincing evidence of the present calculation it follows that in this reign [of Ahmose] Moses was still young” represents the opinion of Syncellus himself, disputing Africanus’s identification.

Africanus, then, does not provide contradictory quotes from Manetho in identifying the name of the Exodus pharaoh as “Ahmose.” He, alongside Syncellus, simply adds his own opinion in preamble to a simple Manethoan listing of pharaohs.

This is further proved by the list of Eusebius.

As for Eusebius?

Syncellus’s quotation from Eusebius for this Manethoan Egyptian dynasty is as follows:

The 18th Dynasty consisted of 14 kings of Diospolis.

The first of these, Amosis [in Africanus as “Amos”], reigned for 25 years.

The second, Chebron, for 13 years.

Ammenophis, for 21 years.

Miphres, for 12 years. … (ibid)

Eusebius follows the same simple Manethoan list found in Africanus. Note, however, that there is no insertion at the start relating to the Exodus pharaoh: This clearly shows that, in following the same king list, it was added to by Africanus and Syncellus with their own personal thoughts and opinions—most certainly not quoting from Manetho in relaying the Exodus pharaoh as Amos/Amosis/Ahmose. But what about the allegation that “Eusebius’s version” of Manetho “claims Akhenaten as king of the Exodus”?

In Syncellus’s publication, we have an insertion within Eusebius’s list of pharaohs:

… Cencheres for 16 years.

About this time Moses led the Jews in their march out of Egypt. (Syncellus adds: Eusebius alone places in this reign the exodus of Israel under Moses, although no argument supports him, but all his predecessors hold a contrary view, as he testifies.)

Acherres, for 8 years. … (ibid)

There is an additional, extant Armenian version of Eusebius, which relays the following:

Achencheres . . . for 16 years. In his time Moses became leader of the Hebrews in their exodus from Egypt.

Acherres, for 8 years. … (ibid)

Here again, it is plain that this reference to Moses is an insertion by Eusebius himself, not original to Manetho in identifying the Exodus pharaoh as Achencheres (or Cencheres; both transliterations reference the same historical Egyptian pharaoh, Akhenaten). As seen in Syncellus’s comment, this opinion as to the Exodus pharaoh is from “Eusebius alone.” It is also seen, again, in simple comparison with the equivalent list of Africanus, which bears no such insertion into the king list at this juncture.

In none of these three other texts, then, do we find anything close to being an assertion from Manetho as to the name of the Exodus pharaoh.

Finally: Josephus’s Manetho

In observing these three later sources referring to text from Manetho, it is instructive to compare them with the earliest quotations of Manetho of them all: those of the first-century Josephus. Rather than just relaying simple king lists, Josephus block quotes literally hundreds of words of Manetho. And unlike the above sources, he repeatedly signposts his quotes in no uncertain terms. As the following examples demonstrate (Against Apion, Book 1):

“Now this Manetho, in the second book of his Egyptian History, writes ….”

“I will set down his very words, as if I were to bring the very man himself into a court for a witness. …”

“Manetho goes on ….”

“Manetho says ….”

“Manetho, in another book of his, says ….”

“I shall therefore here bring in Manetho again, and what he writes as to the order of the times in this case; and thus he speaks ….”

“This is Manetho’s account ….”

“… still Manetho goes on ….”

“These and the like accounts are written by Manetho. …”

“… as Manetho says ….”

“Manetho adds also ….”

These citations of Manetho and his Exodus account are head and shoulders above the others we have seen. (You can read Josephus’s quotations of Manetho in full here.)

But is even the material contained in Josephus itself doubtful? Is it accurate that, as asserted by Falk, “given that Manetho is a third-century b.c. Egyptian priest, chances are that none of them [including Josephus’s account] are the original”? Or that “this Ptolemaic priest wouldn’t have cared, and this is the editorial glossing of later Christian and Jewish writers”?

In simplest comparison, in favor of Josephus’s account is the fact that his text is the earliest of all the sources in question (with the next earliest author, Theophilus, writing a full century later). The above-cited Manetho: History of Egypt and Other Works notes further that, as far as the listing of pharaohs goes, “Africanus gives a less correct list than Josephus (cf. the transposition of Apophis to the end): there is further corruption in Eusebius (Fr. 48) ….”

But there is another key factor here, concerning this question of authenticity in Josephus’s quotations of Manetho: The fact that Josephus disagrees with him.

Josephus, again, has his own opinion as to the Exodus pharaoh in identifying him as Tethmosis (one of the pharaohs named Thutmose). Thus, while quoting Manetho numerous times, Josephus dismisses Manetho’s Amenophis, believing this to be a “fictitious” king (“he mentions Amenophis, a fictitious king’s name” and “he introduces his fictitious king Amenophis”; Against Apion 1.26). Would Josephus invent a name for Manetho’s Exodus pharaoh, only to turn around and argue against it? Certainly not.

But what about a related skeptical opinion that this “Amenophis” found in Josephus’s account may instead have been a pre-Josephan, post-Manethoan added gloss for the name of the Exodus pharaoh—perhaps applied to Manetho’s text somewhere within the intervening period by a Jewish ghostwriter? Here we start to get into the realm of speculative absurdity. Yet in answer to this, there is another point. This is the fact that Josephus brings in another Egyptian text naming the Exodus pharaoh—that of Chaeremon.

Enter Chaeremon’s Pharaoh

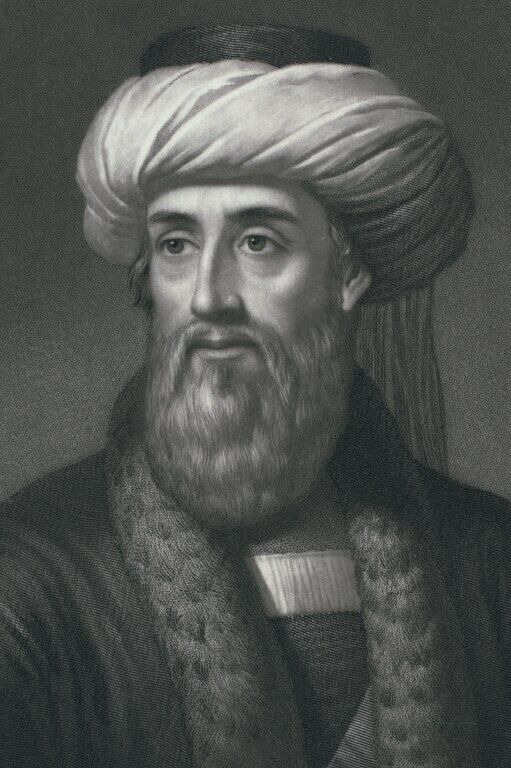

Chaeremon, like Manetho, was an Egyptian priest, historian and philosopher on the scene during the first-century c.e. His writings—originally contained in Aegyptiaca Historia—are likewise lost to history yet are relayed in part through lengthy quotations in Josephus’s Against Apion.

And just like Manetho, Chaeremon also names the Exodus pharaoh: Amenophis.

“And now I have done with Manetho, I will inquire into what Cheremon says,” Josephus states, attempting to dispute the writings of this individual too. “For he also, when he pretended to write the Egyptian history, sets down the same name for this king that Manetho did: Amenophis” (Against Apion 1.32).

What are the chances—if this Amenophis (Amenhotep) was merely an invented name or association, courtesy a Jewish ghostwriter surreptitiously adding the name to then-extant texts—that both Egyptian accounts identified the same individual as pharaoh of the Exodus? And that the Jewish Josephus—in naming these Egyptian sources—attempted to disagree with both of them?

Prof. Miriam Pucci Ben Zeev relays the following counsel in her article “The Reliability of Josephus Flavius: The Case of Hecataeus’s and Manetho’s Accounts of Jews and Judaism: Fifteen Years of Contemporary Research (1974–1900)”:

Modern scholarship has accustomed us to be suspicious. Josephus’ apologetic aims are held as responsible for most of his statements when other sources are not available. But the cases examined above point to the necessity of being cautious. When we say that Josephus lies, or that he is not accurate in citing his source, or that he is not aware of the nature of the source he is using, we must provide proofs.

Pattern of Dismissal

Is Manetho’s reference to “Amenophis” as Exodus pharaoh, then, really so incredibly doubtful and unknowable—particularly in light of the later accounts of Theophilus, Africanus and Eusebius? Not at all. As we have seen, none of these sources—besides Josephus—actually quote Manetho in naming Moses’s opponent. Not only that, but Josephus provides two Egyptian sources that identify him as such, with the very same name.

But this theme of dismissal of such textual sources by late-date Exodus proponents is necessary in making the case for a Ramesside Exodus pharaoh. Be it a dismissal of clues from the biblical account—the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1 as merely “symbolic,” the 300 years of Judges 11:26 as the ramblings of a “blubbering idiot,” the genealogies of 1 Chronicles 6 as “doctored,” the death of the oppression pharaoh in Exodus 2:23 as merely “figurative”; or be it a dismissal of clues from the later extrabiblical accounts and opinions of classical writers—Manetho, Chaeremon, Josephus, Theophilus, Africanus, Eusebius or Syncellus.

After all, when looking at all of these opinions as to the Exodus pharaoh—varied as they are (among the later sources)—none of them align with a late-date Exodus. Conversely, all of these align, to some degree or another, with an early-date Exodus.

Read More:

What Is the Correct Time Frame for the Exodus and Conquest of the Promised Land?

The ‘480 Years’ of 1 Kings 6:1: Just a Symbolic Number?

Jephthah’s ‘Three Hundred Years’: Evidence for the Early Exodus

The 19 Generations of 1 Chronicles 6: Evidence for the Early Exodus

The ‘Raamses’ of Exodus 1:11: Timestamp of Authorship? Or Anachronism?

The Book of Judges Fails to Mention an Egyptian Presence in Canaan—Or Does It?

Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?

The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?

Jericho, Ai, Hazor: Investigating the Three Cities ‘That Did Joshua Burn’

Shiloh Sacrifices: Canaanite Or Israelite?

Amenhotep II as Exodus Pharaoh—With a Low Egyptian Chronology?