Where Is Mount Sinai? Part 2: Journey to Jabal Musa

Where is Mount Sinai, the biblical mountain of God?

In the first installment of this two-part series, we examined the increasingly popular theory about the mountain’s location, not in the Sinai Peninsula, but in Saudi Arabia—the Jabal al-Lawz/Maqla theory. The article concluded that the popular visuals—burned mountaintop, split rock, etc—are false leads and neither this region nor a Gulf of Aqaba crossing fit the data. We also highlighted new research demonstrating that the equivalent name “Sinai” does appear to have been used in ancient Egypt to refer the mountainous southern Sinai Peninsula after all—and that this was not simply a term applied to the peninsula following a later traditional identification of the mountain within it. This is the territory, therefore, in which our Mount Sinai should be found—the same territory already long identified as the location of the mountain of God.

In this article, we’ll focus on the correct identification for the mountain’s location using the best evidence we have: the wilderness itinerary. We’ll retrace the journey of the Israelites down into the southern Sinai Peninsula, specifically to Jabal Musa (“Moses Mountain”), maintaining the case for this as the site of Mount Sinai.

Geographical Map, Theological Map

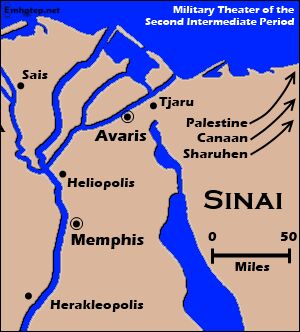

There is agreement for at least the general starting point of the Exodus: The Israelites were based primarily in the “Land of Goshen,” broadly identified with the territory of the eastern Nile Delta. More specifically, their “capital” was a city known as Avaris, as attested to by the classical historians (i.e. the third-century b.c.e. Egyptian Manetho and first-century c.e. Josephus). This site is known today as Tell el-Dab’a. It is also apparent that Moses and Aaron were stationed further south in relative proximity to the Egyptian capital (Exodus 12:31). Other Israelites would likely have been scattered further out, in some cases living among the Egyptians (same verse).

From this starting point to Mount Sinai—with the Red Sea crossing in between—we see a consistent theme as outlined in the Bible: A short journey to the Red Sea crossing, followed by a long journey to Mount Sinai. As we covered in “Where Did the Red Sea Crossing Take Place?”, this is a journey layout that only fits with the traditional site of the Red Sea crossing, at the northern part of the Gulf of Suez. To place the crossing at the other side of the Sinai Peninsula—at the Gulf of Aqaba—would require an immense journey to the crossing and then a comparatively short one to the mountain.

According to the biblical description, the itinerary to the Red Sea features three encampments and one wilderness (Numbers 33:5-7); the journey to Mount Sinai mentions eight encampments and three wildernesses (verses 8-15). Also, it is only during the stretch from the Red Sea to Mount Sinai that the Israelites begin to complain for water and that manna begins to be miraculously delivered.

A shorter journey to the Red Sea followed by a longer journey to Mount Sinai also overlays onto the intrinsic holy day symbolism associated with the Exodus. Following the Passover, the Israelites depart on the eve of the 15th of Abib/Nisan (the first month of the year) on the first high day of Unleavened Bread (Leviticus 23:6-7; Numbers 33:3). Their crossing of the Red Sea has long been associated with the last high day of this seven-day festival (see also Exodus 12:16-17; Leviticus 23:8). The arrival at Mount Sinai six to seven weeks later, at the start of the month Sivan (the third month of the year), culminated in the Israelites receiving the law of God on the next high holy day—Shavuot/Pentecost (Exodus 19:1, 10-11; Leviticus 23:9-22).

We therefore do not only have a general geographical map, but also a theological one. These are maps that, from a starting point in the eastern Nile Delta, fit only with a Red Sea crossing at the northern end of the Gulf of Suez and a Mount Sinai in the Sinai Peninsula.

Thrice Wildernesses, Twice Etham, Twice Red Sea

This logical geographical layout is inferred from the outset in the Numbers 33 itinerary. The three wildernesses highlighted from the Red Sea to Mount Sinai—the wildernesses of Etham, Sin and Sinai (verses 8, 11, 15)—at face value correspond nicely with the tripartite geographical division of the Sinai Peninsula itself, made up of the northern Dune Sheet, central Tih Plateau and the southern mountainous Sinai Massif. As covered in Part 1, the identification of this southernmost mountainous region as this biblical “wilderness of Sinai” would fit precisely with Egyptologist Dr. Julien Cooper’s identification of this as Khety’s “hill-country of Tjenhet.”

This first wilderness, “Etham,” is notable. Numbers 33:6 describes the Israelites about to cross into this wilderness along the normal route before they were “turned back” and became entrapped against the Red Sea. Following their miraculous crossing, they end up in this wilderness of “Etham” again (verse 8)—clearly showing that the crossing was at the northern end of the waterway, adjacent the very same stretch of wilderness and fitting with the layout of Sinai’s first “wilderness,” the nothern Dune Sheet.

Following the Red Sea crossing, we find another peculiarity that only fits with a journey from this point southeast into the southern Sinai Peninsula. After two post-crossing encampments, the Israelites found themselves again at the Red Sea (verse 10). This in no way logically fits with a crossing midway down the Gulf of Aqaba, with al-Lawz located due east. But the Israelites’ arrival once again at the shores of the Red Sea makes perfect sense in a journey to the southern Sinai. Following the initial crossing at the northern end of the Gulf of Suez, the Israelites would necessarily be making their way southeast, where they would arrive at the shores of the Red Sea one final time before cutting in to the hill country.

Stepping back and observing this overall picture, then, clearly favors the traditional route into the southern Sinai. Within this framework, we can zoom in further, with the framework of another map-system.

Encampment Map

Many consider the encampments listed in Numbers 33 to be arbitrary encampments for arbitrary periods of time, spaced arbitrary distances apart—therefore leaving them wide open for geographical interpretation.

In 1971, the late Dr. Herman Hoeh (an employee of our namesake, Herbert W. Armstrong) published a two-part series on the location of Mount Sinai. He and his associate Dr. Ernest Martin—in connection with the Jerusalem excavations carried out in partnership with Prof. Benjamin Mazar and Hebrew University (a partnership that continues to this day)—were guests of the Israeli Military Government of the Sinai, retracing the route of the Exodus from the Red Sea to Jabal Musa.

We have noted the Exodus connection to the annual religious calendar—highlighting Passover, the days of Unleavened Bread and Pentecost. In his journey, Dr. Hoeh emphasized the weekly Sabbath connection of these encampments.

Following a Red Sea crossing on the 21st of Abib (the last day of Unleavened Bread), after a “three days’ journey in the wilderness of Etham,” the Israelites set up their first post-crossing encampment in Marah (verse 8). This would bring us to our first hypothetical “Sabbath” encampment on the 24th of Abib. (Note that the calendar dates of course do not line up with set days of the week; this depends on a detailed reconstruction of when precisely the Exodus took place, the calendar system used to count back to it, and when exactly the encampment began—i.e. if the dates refer to the Friday “preparation day” or the Sabbath alone. Without wading into these specifics, we will simply observe the week-separated dates.)

The next encampment is at Elim (verse 9). No dates are given, but on the hypothesis of Sabbath encampments, that would put this one seven days later—the first of the second month, Iyar. Next, “they journeyed from Elim, and pitched by the Red Sea” (verse 10). Again, no dates are given, but assuming the same system, this would be on the eighth day of the second month.

The next encampment “in the wilderness of Sin” (verse 11) was “on the fifteenth day of the second month” (Exodus 16:1). Dr. Hoeh wrote: “This is exactly a week after the eighth of Iyar, the postulated time of the previous encampment. There can be no doubt. These were Sabbath encampments” (“Visit to Mt. Sinai”; emphasis added throughout).

Moses himself declared at this particular encampment: “This is that which the Lord hath said: To-morrow is the rest of the holy sabbath unto the Lord …. So the people rested on the seventh day” (Exodus 16:23, 30; King James Version).

This pattern of Sabbath encampments would explain other peculiarities, such as why the Israelites encamped at Marah (a place of “bitter waters”) and Rephidim (a place of “no water”). Encampments in such locations would not make sense unless the Israelites were religiously mandated to stop. It is notable that at both locations miracles were performed to provide water (e.g. Exodus 15:25; 17:6).

The spread of Sabbath encampments to Mount Sinai does come with a caveat: For the continuing encampments, there appears to be one too many for all to be on a week-on-week Sabbath basis, in order to align with a giving of the law on Shavuot/Pentecost (more on this further down). Still, even the fact that there would only necessarily be one exception to the rule in this long and unpredictable wilderness journey seems to serve as rather remarkable evidence for the overall pattern. It also indicates that we can expect the distances between these encampments to be relatively the same with roughly four to five days of travel between them—on the basis of the Exodus 16 account, with a Friday preparation day for setting up camp and gathering twice the regular provisions, followed by a Sabbath rest, and then a Sunday takedown and departure.

Considering the immense population, as well as the quantities of livestock and goods (and with most traveling on foot), we should also expect relatively slow daily progress (and with less pressure, now that Israel was out of Egypt). They quite conceivably traveled between 7 to 10 miles per day, with perhaps the majority of the travel in the cooler morning hours. (Yes, the Israelites were led by a “pillar of cloud by day, and the pillar of fire by night”—Exodus 13:22—but note also that this is particularly emphasized prior to the Red Sea crossing, i.e. with the Israelite departure during the night of the 15th and crossing the Red Sea during the night of the 21st.)

With these various “maps”—narrative, geographical, annual sabbath and weekly sabbath—we can zoom in further to plot route specifics.

Station 1: Marah

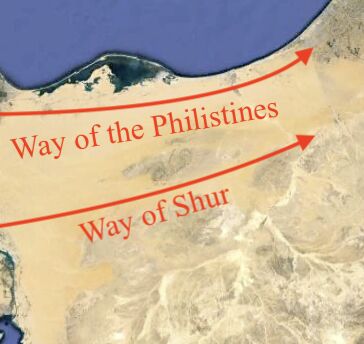

Our first stop following the Red Sea crossing is at Marah: “three days’ journey in the wilderness” (Numbers 33:8). This wilderness is referred to by two different names in the biblical text: The Exodus account primarily refers to it as the “wilderness of Shur” and the Numbers account as the “wilderness of Etham.” The explanation is quite simple: “Shur” is a Semitic word meaning “wall,” and “Etham” appears to be the native Egyptian name. This first wilderness has long been associated with the first of the Sinai Peninsula’s tripartite divisions—the northern Dune Sheet.

Egyptologist James Hoffmeier understands “Shur” to be a geological reference to this northern desert running east-west along the northern “wall”-like edge of the Tih Plateau. This fits with the original Hebrew of Genesis 16:7, which describes the “Way of Shur”—evidently a trade route across the southern part of this Dune Sheet along the Tih Plateau “wall,” linking Egypt with far eastern polities (Genesis 25:18; 1 Samuel 15:7; 27:8). This is in contrast to the northern Mediterranean trade route—the “Way of the Philistines,” a route along the northern edge of the Dune Sheet (Exodus 13:17).

This same vast Dune Sheet, framed by the Tih Plateau “wall,” curls around the northeastern edge of the Gulf of Suez. It, therefore, fits perfectly as the desert that the Israelites were about to cross into initially, following the normal and expected route just north of the Gulf of Suez, as well as being the same region they ended up in, following the sea crossing (Exodus 13:20-22; Numbers 33:6-8).

The specific location of Marah within this region is harder to pinpoint, given the name simply means “bitter.” Interestingly, various water sources in this northwestern Sinai region bear similar names—note the infamous “Bitter Lakes,” as well as Bir el-Mura (relating to the Arabic murr, a designation given by Bedouin to bitter water sources).

Dr. Hoeh also drew attention to Gebel Marah (“Mount Marah”) due east of this crossing point at the Gulf of Suez, southwest of which he believes “the children of Israel must have encamped that first Sabbath in Sinai.” An initial 30-kilometer (20-mile) journey due east to this location, before turning and continuing southeast, would make sense: It would bring the Israelites directly across the open and exposed expanse to the protective edge of the Tih Plateau. In the shadow of its “walls,” the Israelites could continue their long journey southeast, sheltered throughout part of their journey from open exposure.

Station 2: Elim

The next encampment is at Elim. This is noted as a place of palm trees and 12 springs (Exodus 15:17). As an aside, Jabal al-Lawz/Saudi Arabia proponents popularly identify this site with the concrete-reinforced wells of Tayyeb al-Ism, located on the eastern shore of the Gulf of Aqaba. Besides other problematic issues with this identification, these are clearly named in the Bible as springs or fountains (Hebrew עין)—not wells.

In our journey southeast within the Sinai Peninsula, we do come across a region of multiple springs. Dr. Hoeh wrote:

It is significant that, traveling southward from Marah, the next logical stop a week later brings us to the only area in all the Sinai where there are to this day an abundance of natural springs—the region of Gebel Sumar. Present-day maps show 11 springs along several wadis flowing into Wadi Wardan. In Moses’s day these springs—and a 12th one—must have flowed extensively, pouring their waters into the wadi along which the Israelites … encamped that Sabbath, the first day of the second month, Iyar 1.

Station 3: Red Sea

The next encampment is the Israelites’ second arrival at the Red Sea. “And they journeyed from Elim, and pitched by the Red Sea” (Numbers 33:10). This not only makes sense from the perspective of the Israelites traveling southeast into the Sinai, but also due to the Sinai Peninsula topography at this certain point in the journey, where the mountainous southern country creates a choke point with the gulf. With the Israelites hugging the western edge of the Tih Plateau in their journey south, they would have come in direct contact with the Red Sea once again.

“As we journeyed south,” Dr. Hoeh wrote, “the land became more mountainous near the coast along the Gulf of Suez. … The mountains began to hem us in. … Anyone who has traveled this route knows that the only pass along the western Sinai coast is at this point. The children of Israel had no choice but to encamp by the Red Sea.”

Following this encampment, the Israelites begin to make their journey east.

Stations 4-6: Wilderness of Sin, Dophkah, Alush

This is where we encounter a couple of different route possibilities. The next encampment introduces the second wilderness—the “wilderness of Sin.” This could refer to the southwestern end of the second great Sinai division—the Tih Plateau—with an east-then-south journey down to Jabal Musa. Various theories wed this route to a Dophkah (Numbers 33:12) at or around Serabit el-Khadim, and Alush at Wadi al-Ush (verse 13). A differing theory is to identify the wilderness of Sin with the geographically separate sheet at the southwestern end of Sinai Peninsula—passing through the Red Sea chokepoint, in a south-then-east journey, and approaching Jabal Musa up through the main part of the expansive Wadi Feiran. I tend to prefer the former.

Regarding the Sabbath-related encampments following the wilderness of Sin, it is my opinion that at least one of either Dophkah or Alush was not a Sabbath encampment. This is on the basis of allowing for the Israelite arrival at Sinai in the first part of the third month for Shavuot/Pentecost (compare with Exodus 19:1, 11) and on the basis of the final Rephidim encampment being a Sabbath encampment (due to their otherwise-illogical stopping in a location with no water, as well it being in a location so close to Mount Sinai). To this end, it is interesting that the account in the book of Exodus skips over the Dophkah and Alush encampments entirely; Exodus 17:1 goes straight from the Wilderness of Sin to the Rephidim encampment. Only Numbers 33 mentions Dophkah and Alush in the briefest summary. This may suggest that one or both were minor, peripheral encampments.

Yet from a historical standpoint, Dophkah is one of the most interesting: This unusual word has long been noted for its connection with the mining of turquoise. As explained by Egyptologist David Rohl: “Dophkah is Egyptian Du Mafkat, which means the Mountain of Turquoise” (Journey to Mount Sinai).

This parallelism would be near-stunning. In our route, we have now ended up well within the region of “Biau,” within land the Egyptians referred to as “mining country”—specifically, the mining of turquoise. And right within this zip code we have a number of turquoise mines, the most famous of which is Serabit el-Khadim. Not only does this ancient mining site bear some of the earliest Semitic alphabetic inscriptions, dating to the general timeframe of the Exodus (and which may even have connections with the Exodus account)—it also was a prominent site of Hathor worship. Hathor, famously, was the Egyptian goddess symbolized by the cow. Thus the Dophkah encampment would be an excellent fit with this area in or around Serabit el-Khadim. The region’s connection to cow-related worship could aptly explain why some Israelites came to believe that such a deity had rescued them, in their later building and worshiping of the golden calf (Exodus 32).

Given the spread of encampments, it seems to me that Dophkah would be the most likely non-Sabbath encampment. It would only make sense for the Israelites to stop and pillage mining equipment; one even wonders if time might not have even been taken to extract a little turquoise. After all, this substance was later used by the Israelites in the wilderness—notably, in the high priest’s ephod (Exodus 28:18; 39:11—this word nophek is rendered as turquoise in most translations).

Station 7: Rephidim

We now arrive at the final encampment before Mount Sinai. Linguistically, this area would be a good fit with Wadi Refayid, north of Jabal Musa, where, according to Hoffmeier, “the Arabic name appears to preserve Rephidim remarkably well” (Ancient Israel in Sinai, page 170). This location is notable for its proximity to Mount Sinai.

Exodus 19:1 is a highly debated, obscure passage relating the Israelite journey from Rephidim to their final destination: “In the third month after the children of Israel were gone forth out of the land of Egypt, the same day came they into the wilderness of Sinai.” Much has been written on the obscurity of this verse, wondering if “the date of the month has not dropt out” (Keil and Delitzsch Biblical Commentary). Gill’s Exposition provides a handful of interpretations, including the following: “Hither they came either on the same day they came from Rephidim … or rather this was the first day of the month, as Jarchi and R. Moses; with which agrees the Targum of Jonathan.”

It seems to me that both of these opinions are correct. In our pattern of Sabbath encampments (excepting one), the Rephidim encampment would be on the 29th, at the end of the second month of Iyar. With the Israelites encamped at Wadi Refayid, at the very edge of the Sinai Massif’s mountainous interior, it would mean that the continuing Israelites not only would be entering this “wilderness of Sinai” the same day as their departure from Rephidim, but also on the first day of the third month. Following their entrance into the wilderness of Sinai, Jewish tradition (which Gill continues to elaborate on) holds that it took a few days before the Israelites were fully arrived and set up before Mount Sinai, before Moses received the instructions that the Israelites were to “be ready against the third day” (verse 11) for their interaction with God on the day of Shavuot/Pentecost, the week after their departure from Rephidim.

This, then, highlights just how close the Israelites were to their destination while at Rephidim. And having been driven away from a lush Alush (pun intended) so close to their final destination—yet not quite making it to Sinai before the Sabbath hit—this could help explain the near-murderous reaction of the Israelites to Moses due to the lack of water (Exodus 17:4).

Rephidim’s proximity to Mount Sinai is further highlighted by the subsequent miracle that took place.

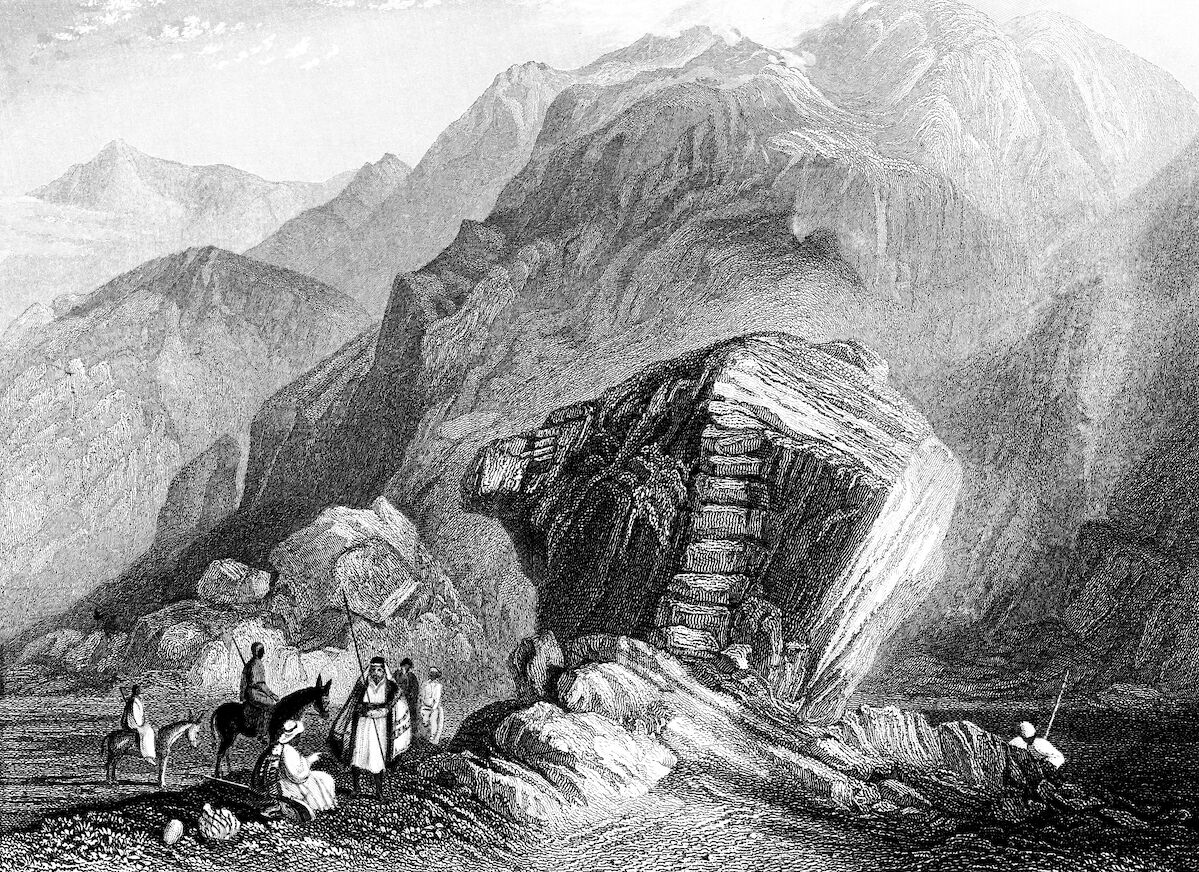

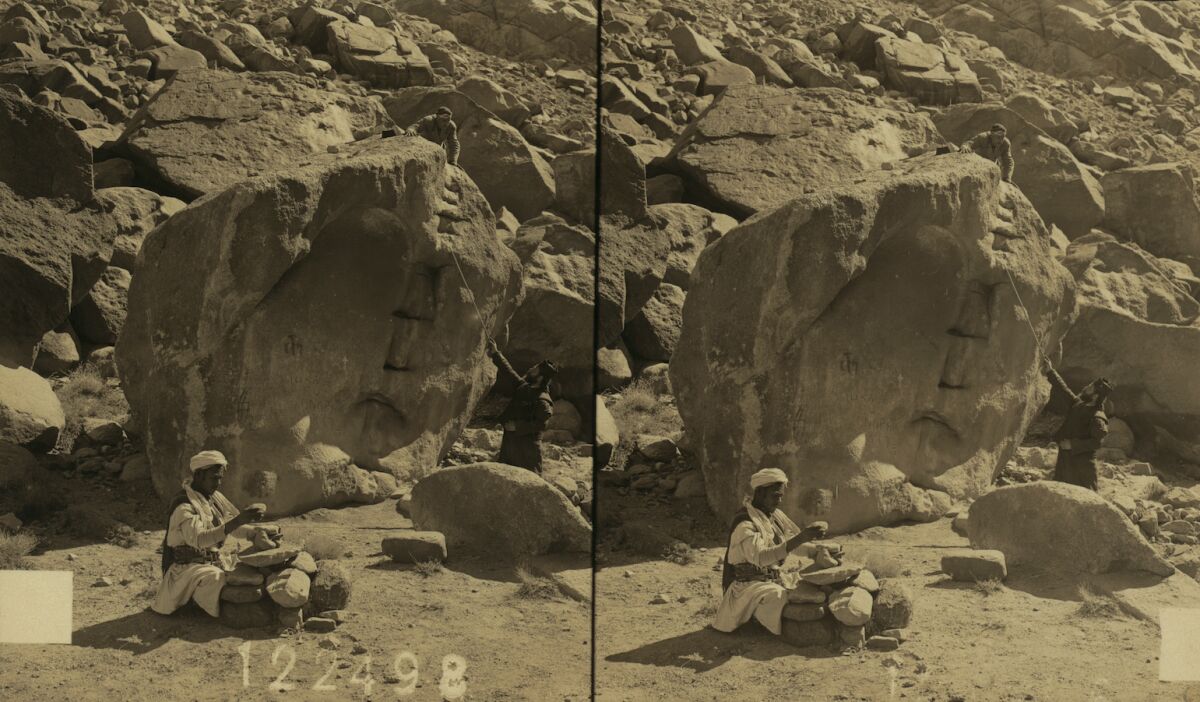

Hajar Musa

“And the Lord said unto Moses: ‘Pass on before the people, and take with thee of the elders of Israel; and thy rod, wherewith thou smotest the river, take in thy hand, and go. Behold, I will stand before thee there upon the rock in Horeb; and thou shalt smite the rock, and there shall come water out of it, that the people may drink’” (Exodus 17:5-6).

This miracle rock “in Horeb” emphasizes just how close the Israelites at Rephidim were to Horeb/Mount Sinai. Dr. Hoeh sets the scene, introducing one very peculiar boulder on the slopes of the mountain of God. Dr. Hoeh is almost beside himself in describing this feature:

[W]hile the children of Israel were temporarily encamped in Rephidim, the elders of Israel hurriedly accompanied Moses to Horeb. Horeb was near Rephidim.

Moses took off in a fast pace up the wadi southward to Horeb, where Mt. Sinai is located. And there … we saw what must be the rock Moses struck!

It is the only rock in all Sinai with 12 natural water stains indicating where water once supernaturally flowed out of the side of the rock! It is not a natural outcrop of rock. It is a fallen angular boulder lying near the western foot of Mt. Sinai on the edge of the wadi. ([Former Sinai Governor-General] Major Rothem and several bedouin children led us to it after we had climbed Mt. Sinai.)

It is one of the most remarkable evidences of divine miraculous power preserved anywhere in stone. The water could not have been from a natural spring, because this rock is not an outcrop through which springwater might naturally seep. It is one of many fallen boulders around Mt. Sinai, but the only one with water stains!

This remarkable feature is known in Arabic as Hajar Musa—“Moses Rock.” Split rock of al-Lawz aside, this enormous monolith is a fascinating specimen, long associated with the miracle in Christian and Muslim tradition. Joel Cook, a Republican politician from Pennsylvania, traveled to the Sinai in the early 1900s. He described this feature as “the Rock of Horeb, whence the spring issued when the rock was struck by Moses. … It is about 12 feet high, of reddish-brown granite, having an oblique band of porphyry on the southern side, the water flowing in jets from holes in this band, one for each of the 12 tribes. Ten of the holes are still visible” (The Mediterranean and Its Borderlands, Vol. II, 1910, page 451).

This links to the description of the rock in the Qur’an, which accords that after the rock was struck by Moses, “twelve springs gushed out” (Al-Baqarah 2:60). It also links more generally to the biblical description—one of a rock, singular, from which a number of streams, plural, issued out (e.g. Psalm 78:16).

Finally: Mount Sinai

Continuing south from Rephidim, the Israelites quickly entered the wilderness of Sinai proper and within a day or two came upon their destination.

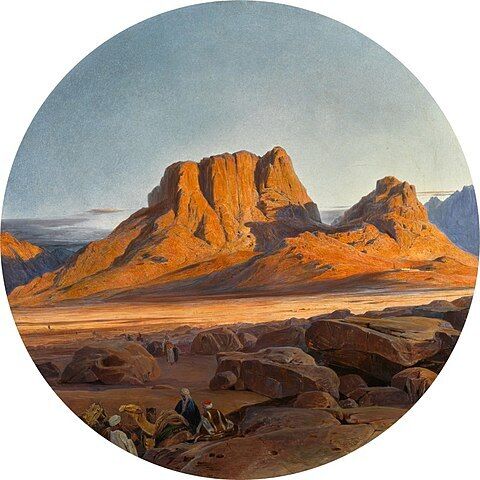

They would have entered through a valley that immediately opens up into the sweeping er-Rahah plain (Rahah meaning “rest”), which stands before the mountainside. In the words of the late Egyptologist Prof. James Phillips: “[I]n front of what is traditionally Mount Sinai, there is a large plain called the Plain of Rahah, of which we have wonderful drawings by [artist David] Roberts in the 1850s …. I know of no other place in Sinai that can replicate that, the two conditions: Tall mountain, and a plain in front of it” (Journey to Mount Sinai).

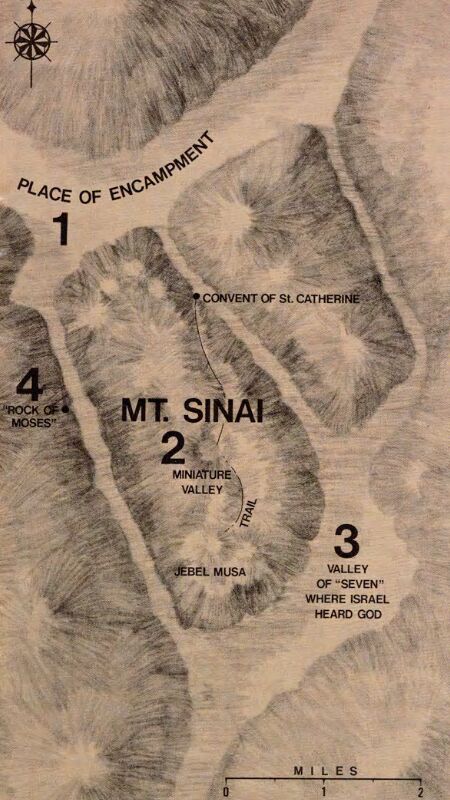

Below left is a map provided by Dr. Hoeh for the area. Note the er-Rahah plain on the north (number 1 on the map), the Convent of St. Catherine at the base of the mountain on the northeast; and the location of Hajar Musa on the left (number 4). Here we must explain a peculiarity about the lay of the land.

In discussing this location of Mount Sinai, it is sometimes referred to jointly or separately as Jabal Musa/Ras Safsafah. Jabal Musa, as depicted, is specifically the highest peak of this outcrop, at the southern end of the map. The lower cliff face at the northern end, in front of the place of encampment, is called Ras Safsafah (“Willow Peak”). This has led some to propose either Ras Safsafah as Mount Sinai, or Ras Safsafah as Horeb and Jabal Musa as Mount Sinai. The latter is the traditional explanation. (In the case of Dr. Hoeh’s map, he delineates the entire range as Mount Sinai.)

This geographical separation is quite remarkable and allows for interesting speculation. If we are to interpret Horeb as this frontal area of Ras Safsafah, it would fit with the Israelites being encamped specifically in front of “mount Horeb” (Exodus 33:6; Deuteronomy 1:2, 6, 19). It would fit with it being in closer proximity to Hajar Musa (as the Rock of Horeb), as well as with the location of the burning bush, down at the traditional site of the convent (Exodus 3:1). It was also in “Horeb” that the Israelites made their golden calf (Psalm 106:19).

It would make additional sense for the higher Mount Sinai peak, Jabal Musa, to be hidden behind—separate and undefiled, in a sense. This very peculiar “hidden peak” would explain Moses’s complete disappearance out of sight for 40 days and nights, with the Israelites wondering where he was. It also would explain why Moses could not see Israel’s golden calf incident—only hearing the revelry from afar and only coming across the site when he was already down from the mountain, turning and entering into the camp “beneath the mount” (Exodus 32:19)—at the base of the Horeb cliff-face.

Clergyman David Austin Randall, who traveled into the area in the 1860s, marveled at the site: “The bold and frowning front of Horeb was directly before us, rising up from the plain in an almost perpendicular wall from two to three thousand feet into the air. The site was grand and majestic beyond description” (The Handwriting of God in Egypt, Sinai, and the Holy Land, page 285).

He also noted another important prerequisite for the mountain—a flowing water source: “A few rods from us, flowing directly from a crevice in the granite rock of the mountain was a copious stream of pure sweet water. How refreshing, after the stale water we had so long drank!” (page 286). Such a necessary water source is alluded to in the biblical text: When the Israelites arrived at the mountain, they were told to “wash their garments” (Exodus 19:10). Rohl added that “there are 20 springs within 10 to 15 minutes’ walk from that campsite [at er-Rahah] … plenty of water in this region to sustain a very large group of people” (Journey to Mount Sinai).

Randall’s sentiments are much the same as those in the earliest pilgrimage account we have for Mount Sinai: The Pilgrimage of Egeria. Egeria (or Etheria) was a woman who traveled to the region in the early 380s c.e. She wrote:

[W]e came on foot to a certain place where the mountains, through which we were journeying, opened out and formed an infinitely great valley, quite flat and extraordinarily beautiful, and across the valley appeared Sinai, the holy mountain of God.

The whole distance from that place to the mount of God was about 4 miles across the aforesaid great valley. For that valley is indeed very great, lying under the slope of the mount of God, and measuring, as far as we could judge by our sight, or as they told us, about 16 miles in length, but they called its breadth four miles … this is the great and flat valley wherein the children of Israel waited during those days when holy Moses went up into the mount of the Lord and remained there 40 days and 40 nights. This moreover is the valley in which that calf was made, and the spot is shown to this day, for a great stone stands fixed there on the very site. …

Now the whole mountain group looks as if it were a single peak, but as you enter the group, there are more than one; the whole group however is called the mount of God. But that special peak which is crowned by the place where, as it is written, the glory of God descended, is in the center of them all. And though all the peaks in the group attain such a height as I think I never saw before, yet the central one, on which the glory of God came down, is so much higher …. This is certainly very wonderful, and not, I think, without the favor of God, that while the central height, which is specially called Sinai, on which the glory of the Lord descended, is higher than all the rest, yet it cannot be seen until you reach its very foot.

She noted various caves in the area, relating them to Moses and Elijah—also fitting the mountain’s biblical prerequisites.

Some approaching the Ras Safsafah face through the er-Rahah plain have not been so immediately impressed. One was Dr. Henry Fields who, arriving at the location in 1882, immediately wondered whether this really was the location of the mountain of God. Yet “when I reached the summit and looked down into the plain of Er-Rahah, I saw the conditions were met, and no longer doubted that I was standing on the holy mount” (On the Desert: With a Brief Review of Recent Events in Egypt, page 114).

Ninteenth-century historian Dean Stanley drew the same conclusion, gushing:

No one who has approached the Ras Sufsafeh through that noble plain, or who has looked down upon the plain from that majestic height, will willingly part with the belief that these are the two essential features of the view of the Israelitish camp. That such a plain should exist at all in front of such a cliff is so remarkable a coincidence with the sacred narrative as to furnish a strong internal argument … of the scene itself having been described by an eyewitness. The awful and lengthened approach, as to some natural sanctuary, would have been the fittest preparation for the coming scene. The low line of alluvial mounds at the foot of the cliff exactly answers to the “bounds” which were to keep the people off from “touching the mount.” The plain itself is not broken and uneven, and narrowly shut in, like almost all others in the range, but presents a long retiring sweep …. The cliff, rising like a huge altar, in front of the whole congregation, and visible against the sky in lonely grandeur from end to end of the whole plain …. Here, beyond all other parts of the peninsula, is the adytum [innermost sanctuary], withdrawn, as if in the “end of the world,” from all the stir and confusion of earthly things! (Sinai and Palestine: In Connection With Their History, pages 42-43).

Additional, peripheral points could be made for this location as the correct one. One is Deuteronomy 1:2, which says it was an “eleven days’ journey from Horeb unto Kadesh-barnea by way of mount Seir.” Professor Hoffmeier, calculating the distances, notes that “from the region of south Sinai to Kadesh-Barnea via Mt. Sinai fits admirably the prescription of Deuteronomy 1:2, as the other locations scholars usually propose do not. … Edward Robinson’s trek in 1838 from Gebel Musa in southern Sinai to ‘Ain Qadis, a suggested location for Kadesh … took precisely 11 days” (Ancient Israel in Sinai, pages 144, 123).

What about olives? Arab tradition, as well as the Qur’an itself, asserts Mount Sinai as a place of olives (Al-Mu’minun 23:20; At-Tin 95:1-2). Abdullah Yusuf Ali goes so far as to write that “the best olives grow round about Mount Sinai” (The Holy Qur’an, page 877). This presence of olive trees is also implied in the biblical account, where instructions are given to the Israelites to begin using “pure olive oil” in tabernacle-related rituals (e.g. Exodus 27:20; 30:24; Leviticus 24:2). To this day, an impressive abundance of fine olive trees grow on the sides of Jabal Musa, including a large olive grove containing some 700 trees.

Some will also find it fitting that at this location of the giving of the Torah, one of the oldest and most complete biblical manuscripts (and the oldest complete copy of the New Testament)—Codex Sinaiticus—was discovered in 1844.

Why the Level of Debate?

As our study draws to a close, we are left with a final question: Why all the modern debate surrounding the location of Mount Sinai? If this really was the great “mountain of God” shouldn’t its location be obvious and unequivocal? A site for which there is no debate? Though some have been overcome by the aura of this site in the southern Sinai, others have left somewhat disappointed. Why?

Alongside the biblical account, we have seen the emphasis of early Christian, Arab and Muslim tradition on this site in southern Sinai. But in answer to this question in particular, Jewish tradition comes to the fore. Famously, there is no strong Jewish opinion on the location of the mountain (though as noted by al-Lawz proponent Glen Fritz, there is at least some general deference toward Jabal Musa, or this south Sinai region). This comparative ambivalence is aptly summed up in Sarah Ogince’s recent Israel Today article, “Christians More Interested Than Jews in Location of Mount Sinai.”

Yehuda Sherpin in his Chabad article “Where Is Mount Sinai?” explained: “Once the Jewish people received the Torah on Mount Sinai and continued their journey to the Land of Israel, there is just one biblical mention of anyone going back to Mount Sinai. … Mount Sinai itself was not inherently holy. Rather, what was done there gave honor and holiness to Sinai, so once the people received the Torah and moved on, Sinai was no longer holy.”

It’s an interesting point. Following the Israelites’ journey into the Promised Land, what becomes the “mountain of God”? Jerusalem becomes the mountain in which “I put My name forever” (2 Chronicles 33:7). As the famous passage in Isaiah goes: “‘Come ye, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, To the house of the God of Jacob; And He will teach us of His ways, And we will walk in His paths.’ For out of Zion shall go forth the law, And the word of the Lord from Jerusalem” (Isaiah 2:3). This is near-identical language to that of Sinai—a “mountain of the Lord,” from which comes forth “the law.” Yet this prophecy clearly refers not to the Mount Sinai of old, but to Jerusalem.

Many pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land have been deeply moved by it, by Jerusalem, by Jabal Musa. Yet many others throughout the centuries have quite famously been “often disappointed by the Holy Land”—the various territories not living up to their own imagined expectations. Many modern-day seekers of Mount Sinai, in expressing similar sentiment about Jabal Musa, may not realize quite the level of historical feeling which they are tapping into. Those searching for an innately holy physical mountain, or breathtaking epiphany, will be disappointed. (The modern tourism element does not help the matter either. Ditto for the novelty and comfort of journeying from place to place in suvs. Try traveling through parched wastelands on foot for a month and a half—then see how disappointed you are at your destination!)

At the end of the day, who are we to judge the “impressiveness” of the mountain chosen by God anyway? To this end, long-standing Jewish tradition even holds that this mountain was deliberately chosen because it was not the most impressive. This tradition is commonly associated with Psalm 68:16: “Why from your mighty peaks do you look with scorn on the mountain on which God chose to live?” (Good News Translation).

Case in point Jerusalem—the later “mountain of God”—which is a lower mountain range, shadowed on east and west by the taller Mount of Olives and Western Hill. The Jabal Musa and Ras Safsafah outcrop, while still an imposing sight, is not the very tallest in the wider region (that would be Mount Catherine, to the south), nor does it have the pointiest of peaks (as with Mount Catherine, or Saudi Arabia’s Jabal Maqla and al-Lawz). It is certainly no Mount Everest. Yet some have justifiably argued this as evidence for Jabal Musa not having been artificially selected by a human. Recall the lesson of Jesse and his sons: “But the Lord said unto Samuel, Look not on his countenance, or on the height … for the Lord seeth not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance” (1 Samuel 16:7; kjv).

Sinai in Sum

And so at the end of our study of what might be called the “former” mountain of God—Mount Sinai—what is the most important takeaway? Is it the impressive nature of the mountain? The miracles that took place there? The burning bush? Moses’ radiating face? The geographic particulars? Sherpin’s article tells us—and the last of the biblical prophets tells us, with the last mention of the mountain in the Hebrew Bible, in the very final verses of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament (in the order of most English translations). It’s a call to remember something that is almost ubiquitously forgotten.

“Remember ye the law of Moses my servant, which I commanded unto him in Horeb” (Malachi 4:4; kjv).

In a very real sense, then, we have no need to go “look” for Mount Sinai—it’s right there with us, in the very first pages of our own Bibles.