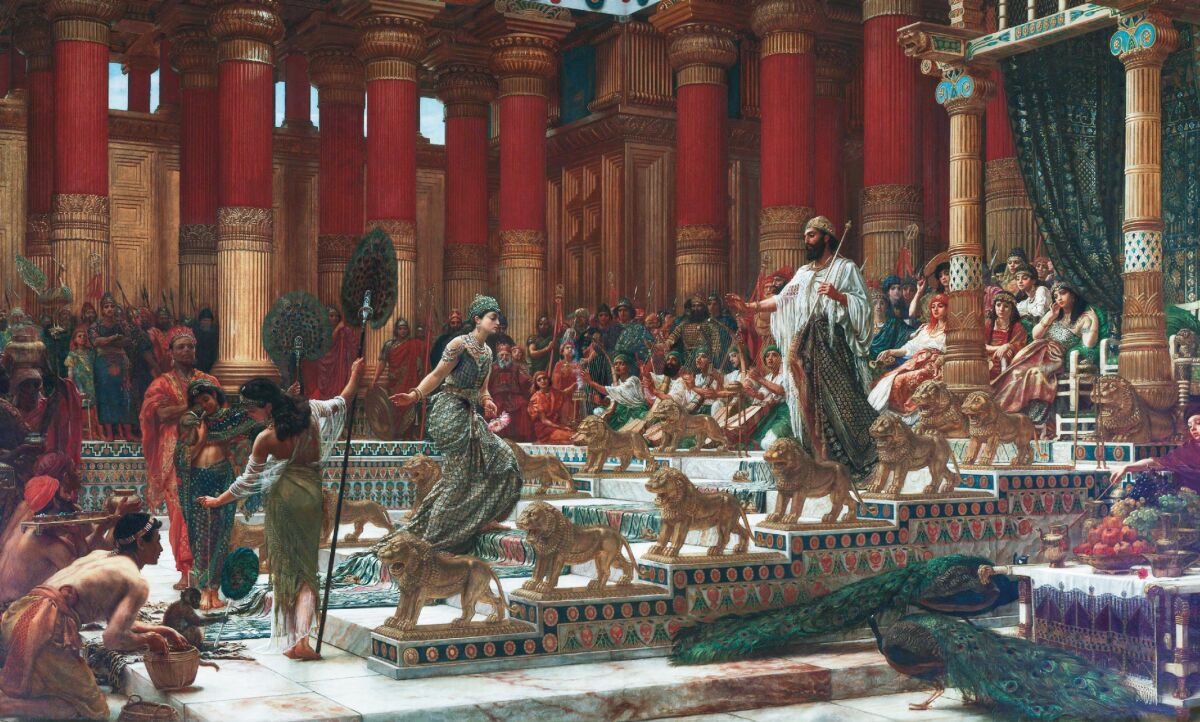

The deafening peal of silver trumpets reverberated between the giant limestone walls of the royal complex. Throngs of curious residents lined the streets; countless others peered down from walls, windows and rooftops. The eager onlookers were hoping to catch a glimpse of their exotic visitor: a queen from a faraway kingdom. She was in Jerusalem to visit with their king, a monarch whose wealth, wisdom and wit “exceeded all the kings of the earth” (1 Kings 10:23).

The Queen of Sheba stepped gracefully away from her caravan and was escorted into the palace. She walked only a few steps inside before she gasped and stood in stunned silence. It was unlike anything she had ever experienced: towering stone pillars with ornate Phoenician-style capitals; walls fashioned from massive handcrafted, polished limestone; sprawling mosaic ceilings; marble floors bejeweled with precious stones; and exquisite purple and gold tapestries. The sheer majesty was stupendous. The queen was soon jolted from her reflections by the sound of footsteps. Israel’s king was approaching.

King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba toured the royal complex, the armory, the stables with Solomon’s prized stallions, the lush gardens, including a small zoo of exotic animals, and of course, the crown jewel of the kingdom: the temple. Israel’s king was a warm and gracious host, and completely transparent: He “answered all her questions” (verse 3; New King James Version).

As the sun set, the queen joined King Solomon for a banquet. This too was a singular and inspiring experience. The table was laden with delicacies from across the kingdom: beef from the Transjordan, dates from the Negev, wine from Jezreel, fish from the port of Joppa. They sipped from goblets made of gold imported from Ophir. The bronze came from Solomon’s mines in Timna and was fashioned by his Phoenician friends. The queen was overwhelmed. “And when the queen of Sheba had seen all the wisdom of Solomon, the house that he had built, the food on his table, the seating of his servants, the service of his waiters and their apparel, his cupbearers, and his entryway by which he went up to the house of the Lord, there was no more spirit in her” (verses 4-5; nkjv).

When the time came to depart, the queen was at a loss for words. Her only recourse was honesty. “I did not believe the words until I came and saw with my own eyes,” she told Solomon, “and indeed the half was not told me. Your wisdom and prosperity exceed the fame of which I heard” (verses 7-8; nkjv). As the queen’s caravan exited the giant gates of Jerusalem, she sighed with relief and anticipation. The long journey through the barren deserts of Arabia would give her time to process all that she had experienced. As she turned to steal one last look, one word sprang to mind. This was, she thought, monumental.

This is a fantastic scene.

But is it real?

Fact Versus Fiction

This special issue of Let the Stones Speak revolves around the reality of the monumental nature of the kingdom of David and Solomon—what might be the most controversial and complex question in the field of biblical archaeology and scholarship. It isn’t an easy question to tackle. This history, if true, transpired three millenniums ago, more than enough time for evidence to deteriorate and disappear.

The history of Jerusalem, and the region in general, is one of ruin and destruction. The city has been conquered and rebuilt over and again by all manner of peoples. In the words of historian Eric Cline: “There have been at least 118 separate conflicts in and for Jerusalem during the past four millennia …. Jerusalem has been destroyed completely at least twice, besieged 23 times, attacked an additional 52 times, and captured and recaptured 44 times. It has been the scene of 20 revolts and innumerable riots, has had at least five separate periods of violent terrorist attacks during the past century, and has only changed hands completely peacefully twice in the past 4,000 years” (Jerusalem Besieged).

Repeated bouts of demolition aren’t exactly good for the safe-keeping of ancient history and archaeology. Add to this the significant challenges associated with researching and excavating land that sits beneath the most politically and religiously volatile city and territory on Earth, and it is undeniable: This history is difficult to uncover and understand.

Yet does exploring 10th-century b.c.e. Israel need to be as complex and controversial as it is? Why is it this way?

Many Bible believers, as one might expect, accept the biblical description of 10th-century b.c.e. Israel. They accept King David as the mighty warrior-king responsible for completing Israel’s subjugation of the Promised Land. They accept that Solomon ruled a vast and wealthy kingdom, constructed the greatest temple ever built, and was the envy of kings.

Bible historians and biblical archaeologists generally have much more nuanced views of the biblical text. Some will accept the historicity of a biblical united monarchy, but only as and when the archaeological evidence supports it. For most biblical archaeologists, the Hebrew Bible is more a helpful supplement than a principal source.

Finally, there are the Bible skeptics and minimalists. In this group is a spectrum of cynicism. Some are much more suspicious than others. There was even a time when hardcore skeptics doubted the very existence of David and Solomon, to say nothing of the presence of any kingdom to speak of. This view significantly changed after inscriptional evidence of King David was discovered in 1993.

Today, even the staunchest Bible critics recognize David as a historical figure. But the tide of criticism remains high. Many academics and archaeologists, as well as journalists, still view the biblical text as mostly fictional and a wholly unreliable source of history.

The reality is that, for most scientists and historians trained within an educational system that rejects the Bible and detests religion, the Bible is consulted, if at all, as an afterthought. Educated to ignore biblical history while at university, they ignore biblical history in their profession.

This is one reason the discussion and debate around David, Solomon and 10th-century Israel carries on ad infinitum: The historical record, which provides crucial detail and clarity, is left out of the conversation.

A Jigsaw Puzzle

How accurate is the Bible’s description of David and Solomon’s kingdom? Answering this question is a lot like doing a jigsaw puzzle. Like a puzzle, the view that David and Solomon were powerful kings who presided over a large, prosperous kingdom is comprised of several constituent parts. This is not unusual. Every historical figure, civilization or event is multidimensional, and to gain a complete understanding, one must consider all the pieces.

Take Napoleon, for example. To truly understand the “little corporal,” one must study his childhood, education and personality; the political, financial and social conditions of revolutionary France; and the geopolitics of early 19th-century Europe—to name only a few puzzle pieces.

The same is true of the kingdom of Israel in the 10th century b.c.e. To build a complete picture, we must locate and consider every available piece of the puzzle. Individual pieces can be interesting and informative, and might hint at the overall picture, but the ultimate potential of an individual piece to educate and inspire is manifested only when placed alongside the other pieces as part of the larger tableau.

This is what we have endeavored to do in this issue of Let the Stones Speak and with our “Kingdom of David and Solomon Discovered” exhibit. We have attempted to put together what has been considered an impossible puzzle.

When it comes to kings David and Solomon, and the nature of 10th-century b.c.e. Israel, this puzzle has never been completed! This is surprising considering the importance of the subject. David and Solomon might have reigned over 3,000 years ago, but they remain two of the most epic figures in ancient history. Yet remarkably, no archaeologist or Bible historian has ever collected the pieces and put them together in their entirety to create one overall picture.

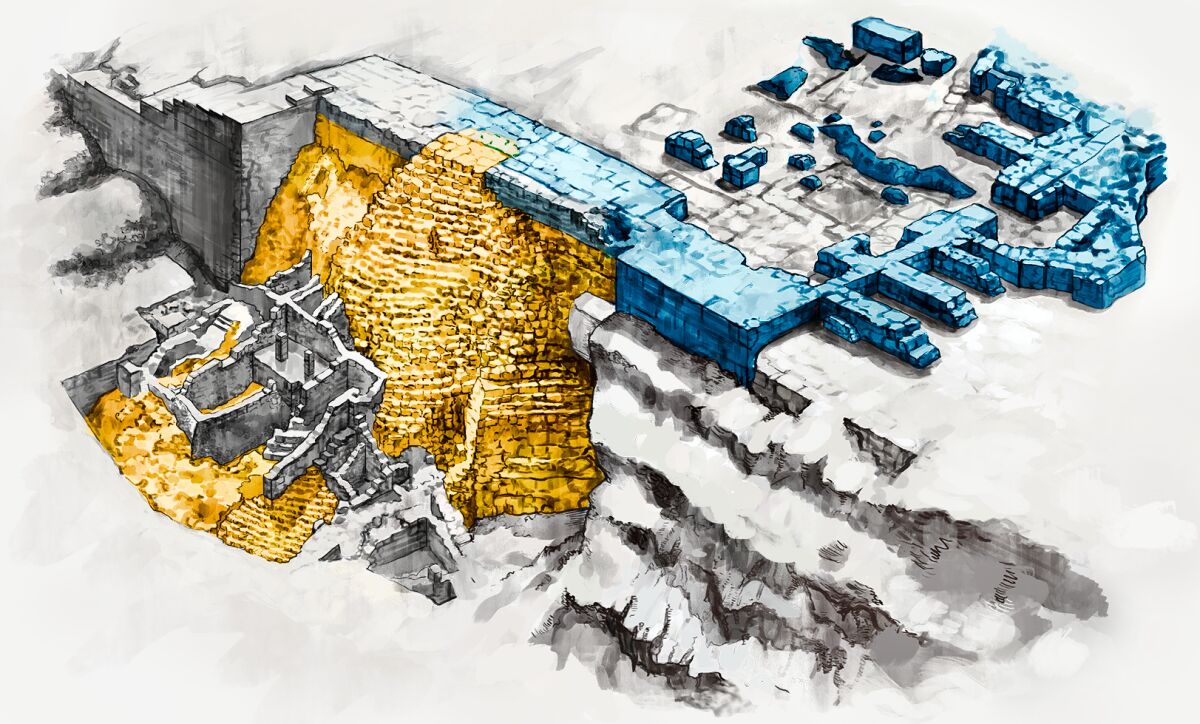

There are experts who specialize in specific puzzle pieces. The late Hebrew University archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar possessed a masterful understanding of 10th-century Jerusalem, including the Stepped Stone Structure and the Large Stone Structure (King David’s palace). Dr. Mazar had an unmatched grasp of the monumental structures and artifacts on the Ophel that attest to Solomonic Jerusalem.

Dr. Mazar’s archaeology in the City of David and the Ophel certainly testified to the united monarchy documented in the Bible. But Dr. Mazar focused on only three or four pieces of the puzzle. These must be considered alongside many other distinct pieces of evidence.

Prof. Yosef Garfinkel from Hebrew University has done fantastic work excavating 10th-century b.c.e. biblical sites such as Khirbet Qeiyafa. These sites reveal the territorial spread of the kingdom, as well as urban planning by a centralized government, providing further pieces of the puzzle.

The same can be said for archaeologist Dr. Erez Ben-Yosef and his brilliant work uncovering the 10th-century b.c.e. copper mines in the Arabah Valley in southern Israel. Then there are the late Prof. Yigael Yadin, Prof. William Dever and Prof. Amnon Ben-Tor, with their study of Solomon’s gigantic gatehouses in Megiddo, Gezer and Hazor. Each of these is one piece of a much larger picture.

All the pieces have never been combined—until “Kingdom of David and Solomon Discovered”!

The Biblical Guide

Before we start assembling the puzzle, consider one last crucial parallel: What makes the completion of a jigsaw puzzle possible? On every puzzle box is a picture. This illustration is the guide. It informs one of what pieces to look for and shows where they fit in the larger scene.

Without this image, all you have are a bunch of seemingly random pieces. Completing the puzzle without the guide is an almost impossible task.

To complete the “Kingdom of David and Solomon Discovered” puzzle, the Bible provides this illustration.

Unfortunately, this a problem for some. Cynics and minimalists claim the Bible cannot be trusted, even as a historical source. “First and foremost, … the Bible does not mean to speak history. The Bible is all about theology, about ideology … and we scholars, researchers, need to speak facts and data” (emphasis added throughout issue). Prof. Israel Finkelstein, perhaps the most outspoken biblical minimalist, made this remark, and others like it, in a 2020–2021 interview series hosted by the W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research. Notice the preface of his remark: “[f]irst and foremost.” This is fundamental in the approach skeptics take to archaeology and science: The biblical record is not a history book.

This is why the question of the monumental nature of the kingdom of David and Solomon has never been sufficiently explored and answered.

And yet how can you discuss, let alone research and study, biblical history without at least objectively considering actual biblical history?

Bible skeptics and minimalists distrust the Bible. For the most part, they will not read it objectively. To critics, most of the biblical record is pure fiction, even though this accusation is demonstrably false. Take, for example, Assyria’s eighth-century b.c.e. invasion of Israel and Judah. Compare the biblical account with the archaeological record and Assyrian history. The synergy across all three dimensions is remarkable and proves that the Bible does speak history.

Those who ignore and reject the biblical text consider anyone who employs the Hebrew Bible as religious or spiritual—a fanatic, driven by ideology and bias. And to most modern scholars and scientists, there is no worse epithet than the label religious.

Ironically, rejecting historical texts is neither logical nor scientific. Archaeologists and historians studying ancient Greece consult Herodotus, Homer and Thucydides without dread of being labeled Hellenistic paganists. When they study ancient Egypt, they consult the historian and priest of Ra, Manetho—again, without fear of being pilloried as a sun worshiper. Yet an archaeologist or historian cannot study ancient Israel and too closely consult the Hebrew Bible without being disdained or having his work marginalized and rejected.

It takes some courage to enter the world of biblical David and Solomon. The truth is, no matter what the skeptics might think, consulting biblical history is not a religious or spiritual experience. There are theological dimensions to the subject, but one is not miraculously “converted” merely by considering the history recorded in the Hebrew Bible. In spite of what modern education teaches, the Bible and science are not mutually exclusive. You can use both.

In fact, to complete this puzzle, we need both!

There is nothing religious or spiritual in the “Kingdom of David and Solomon Discovered” exhibit or in this special issue. Our aim is simple: We want to present all the pieces of the puzzle that is David, Solomon and the 10th-century b.c.e. kingdom of Israel. To do this, we must consider all the facts and evidence. This means studying the archaeology: the walls, gatehouses and cities, the pottery, inscriptions and textiles. It also means considering the historical text: the Hebrew Bible.

Before we begin, let’s look at what the biblical text records about the united monarchy and Israel in the 10th century b.c.e.