3,000-Year-Old Phoenician Electrum Earring Pendant Discovered in Jerusalem

“And Hiram King of Tyre sent his servants unto Solomon: For he had heard that they had anointed him king in the room of his father: for Hiram was ever a lover of David.” –1 Kings 5:1

The Bible relates that during the period of the United Monarchy in 10th-century b.c.e. Israel, a close relationship developed with the Phoenicians, a people situated northwest of Israel in a collection of city-states on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Immediately following David’s capture of Jerusalem around 1000 b.c.e., King Hiram of Tyre (a dominant city-state) sent Lebanon’s famed cedarwood, along with stonemasons and carpenters, to help Israel’s king construct a lavish palace in the northern part of the City of David (2 Samuel 5:11). 2 Samuel 24:7 even includes Tyre in the census David commissioned Joab to undertake near the end of his reign, suggesting that Tyre was an extremely close ally.

The friendship between Israel and Phoenicia continued after David’s death (2 Chronicles 2:2). 1 Kings 5 states that when Solomon was crowned, King Hiram sent a delegation to Jerusalem to congratulate the new king. Solomon later hired the Tyrians to supply cedar for the construction of the temple (2 Chronicles 2:7, 15). Along with the Phoenician builders, King Solomon also requested King Hiram supply cunning artificers and craftsmen skilled in metalworking and clothing manufacturing. These skilled Phoenician laborers worked in Jerusalem during the construction of Solomon’s new royal quarter on Jerusalem’s Ophel (an area located between the City of David to the south and the Temple Mount to the north).

The Bible records King Hiram’s description of one particular craftsman: “He is trained to work in gold, silver, bronze, iron, stone, and wood, and in purple, blue, and crimson fabrics and fine linen, and to do all sorts of engraving and execute any design that may be assigned him, with your craftsmen, the craftsmen of my lord, David your father” (2 Chronicles 2:14; English Standard Version). The biblical account clearly reveals that numerous Phoenician representatives were in Jerusalem’s royal quarter during the 10th century b.c.e.

Now, thanks to the discovery of a uniquely Phoenician piece of jewelry on the Ophel, we have compelling archaeological evidence of a 10th-century Phoenician presence in Jerusalem.

A Tale of Discovery

The renewed Hebrew University Institute of Archaeology Ophel excavations, directed by the late Dr. Eilat Mazar, began in 2009 and continued until her last excavation season in 2018. The area had been excavated in the 1970s by Eilat’s grandfather and former president of Hebrew University, Prof. Benjamin Mazar. Motivated by the encouragement of her grandfather, and thanks to the generous donations of Daniel Mintz and Meredith Berkman, Eilat was able to conduct multiple large-scale excavations on the Ophel, together with a large contingent of volunteers and students from Herbert W. Armstrong College in Edmond, Oklahoma.

Monumental walls were discovered throughout the area, which Dr. Mazar dated to the 10th century b.c.e.—the time period including King Solomon. Equally important were the numerous tiny artifacts inside the occupational layers; finds that typically would have been missed were it not for Eilat’s trailblazing use of wet sifting. (Wet sifting involves taking excavated earth, putting it through a sifter and spraying it with water—this helps to separate and reveal miniature objects within the earth that might otherwise have gone undetected.)

It’s an extremely labor-intensive process, but Eilat insisted that we wet sift all Iron Age material. This meticulous practice led to the discovery of the two oldest pieces of writing ever found in Jerusalem—cuneiform tablet fragments from the 14th and 13th centuries b.c.e.—as well as dozens of seals and seal impressions, the most notable being the personal seal impression of King Hezekiah.

In the world of archaeology, it is not rare for there to be a long period between the moment an artifact is plucked from the ground and when it is finally studied and identified. On the Ophel dig, small artifacts discovered during wet sifting were documented, boxed up and taken to the lab to be analyzed at a later time. In the case of Hezekiah’s seal impression, there was a five-year gap between when it was first taken from the ground and then identified and revealed to the public.

In the case of this piece of Phoenician jewelry, it was just over a decade.

The Ophel Electrum Basket Pendant

During the 2012 excavation, I was area supervisor over Area B, working under Dr. Mazar. The dig lasted five months. During the final two months, we were mainly excavating early Iron iia walls, fills and floors. (The full stratigraphy study of Area B will be published by Dr. Ariel Winderbaum in the forthcoming Volume iii of The Ophel Excavations to the South of the Temple Mount, 2009–2013: Final Reports.) The excavations were also completed in conjunction with the National Parks Authority, East Jerusalem Development Fund, and with the approval of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The responsibility of supervising kept me extremely busy, and I wasn’t able to keep abreast of the finds being revealed through wet sifting (conducted on-site by a separate team). Therefore, I wasn’t aware of the discovery of an exquisite golden object, smaller than a shekel or dime, until years later when I began to work on publishing the final reports of the excavation (particularly after the death of Dr. Mazar in 2021). Officially known as the Ophel Electrum Basket Pendant, the full publication of this object will be included in the aforementioned Final Reports Volume iii, alongside Iron Age jewelry expert Dr. Amir Golani.

Early in 2023, I came across the pendant while searching through some unpublished finds from Area B in Eilat Mazar’s office (which once belonged to Prof. Benjamin Mazar and is now a hub of activity as Eilat’s sister, Avital Mazar-Tsairi, oversees the important task of completing the remaining publications of Eilat’s excavations).

The pendant, with its intricate design and spectacular golden luster, immediately arrested my attention. When I picked it up, I was struck by how heavy it was for such a tiny item.

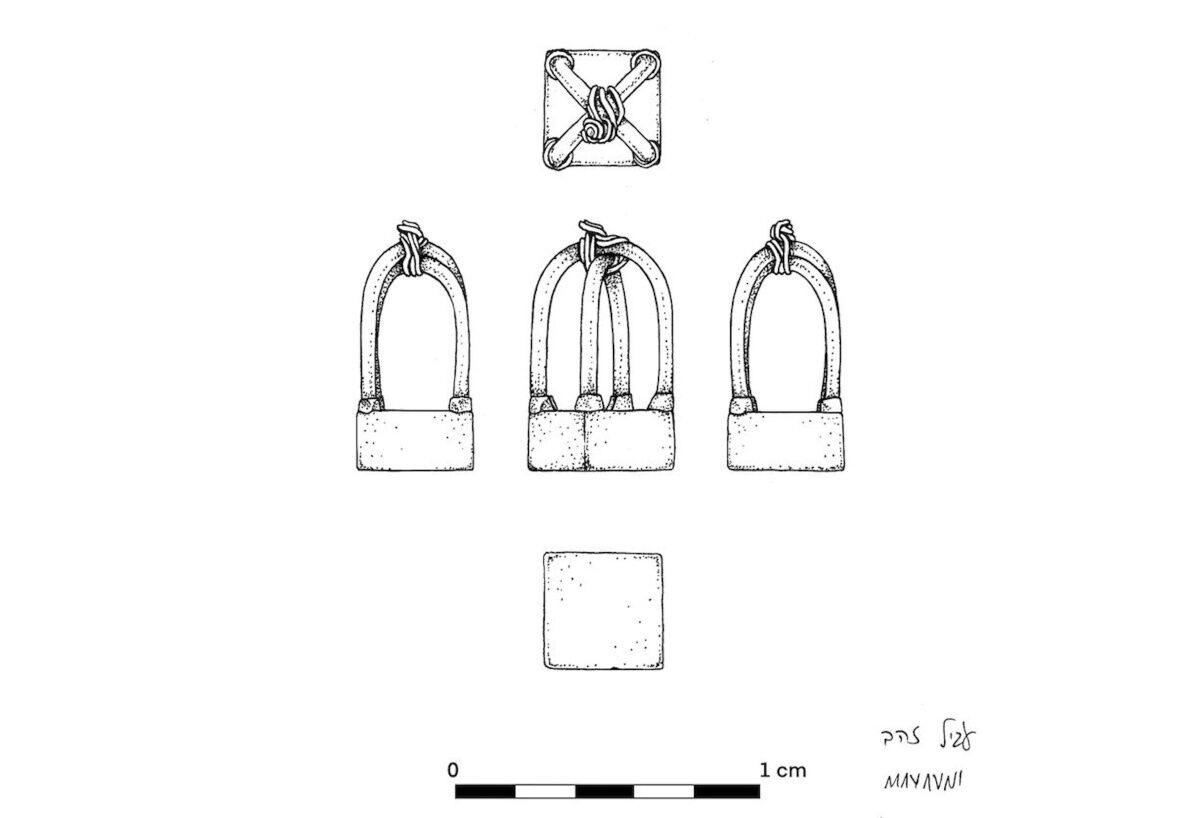

The basket pendant’s box is completely solid, measuring 4 x 4 x 2 millimeters. Two tubular parabolic handles, measuring just 0.5 mm in diameter, are attached to the corners of the basket and rise 6 mm above the top of the basket. An even narrower gold wire is tightly wrapped around the base of each parabolic handle, making a knop—perhaps an ancient artistic embellishment to hide the joint of the bars to the base. The top of the parabolic bars are joined together by golden wire wrapped three times around and then extending upward where it is snapped. The wire was probably originally connected to a suspension loop.

When I initially inspected the piece, no one in the office could identify the basket pendant for what it was. Based on its discovery context, Tthe best we could do was label it as a stunning piece of jewelry from an early Iron IIA context (typically associated with 10th-century b.c.e.) Jerusalem. So this is what we did, and then we returned to our other work.

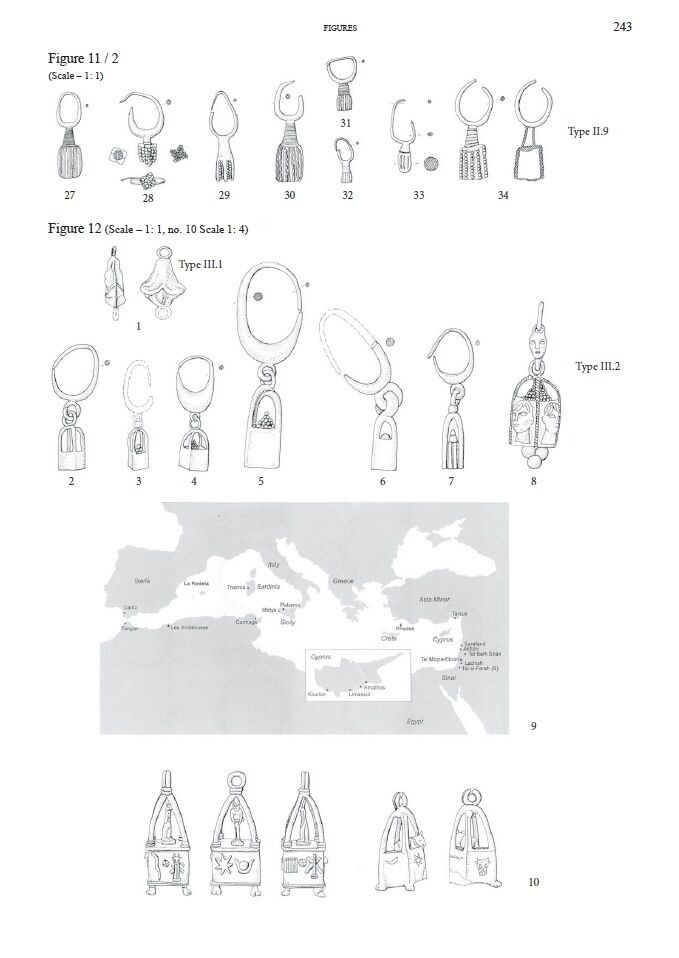

Last year, late in the afternoon of May 30, I had some extra time and decided to skim through Dr. Amir Golani’s 2013 definitive text, Jewelry from the Iron Age II Levant. I wondered if our Ophel jewelry piece had a parallel. And there it was on page 243—a series of basket pendant earrings native to Phoenician sites found across the Mediterranean. The only “problem” was that our Ophel pendant predated most of the other box pendants. Four of Golani’s examples were from Phoenician sites in Sardinia and dated to the seventh-to-sixth centuries b.c.e. Two were from Cyprus and dated to the same time period. Perhaps the most beautiful example—three basket pendants connected to a single earring, discovered at Cadiz in Spain—was also of a later date. As Golani relates, there are many more examples, and all of them were found at exclusively Mediterranean sites directly connected to Phoenician settlement and colonization.

Most of these parallels had several metallic granules sitting on top of the basket inside the parabolic bars. In the past, this had led to naming such items as “ball and cage” pendants. Yet no granules were featured on the Ophel Basket Pendant, nor was there evidence to indicate they had been there but had fallen off. All basket pendants found outside the Levant were discovered only at sites commonly associated with Phoenician colonies anchoring the “cultural attribution of this pendant type to the Phoenicians,” Golani writes. They are, without doubt, a purely Phoenician phenomenon, found only where there was a physical Phoenician presence. Considering earrings have a direct frontal display, they are intended to transmit information about the wearer. This makes this a very personal object.

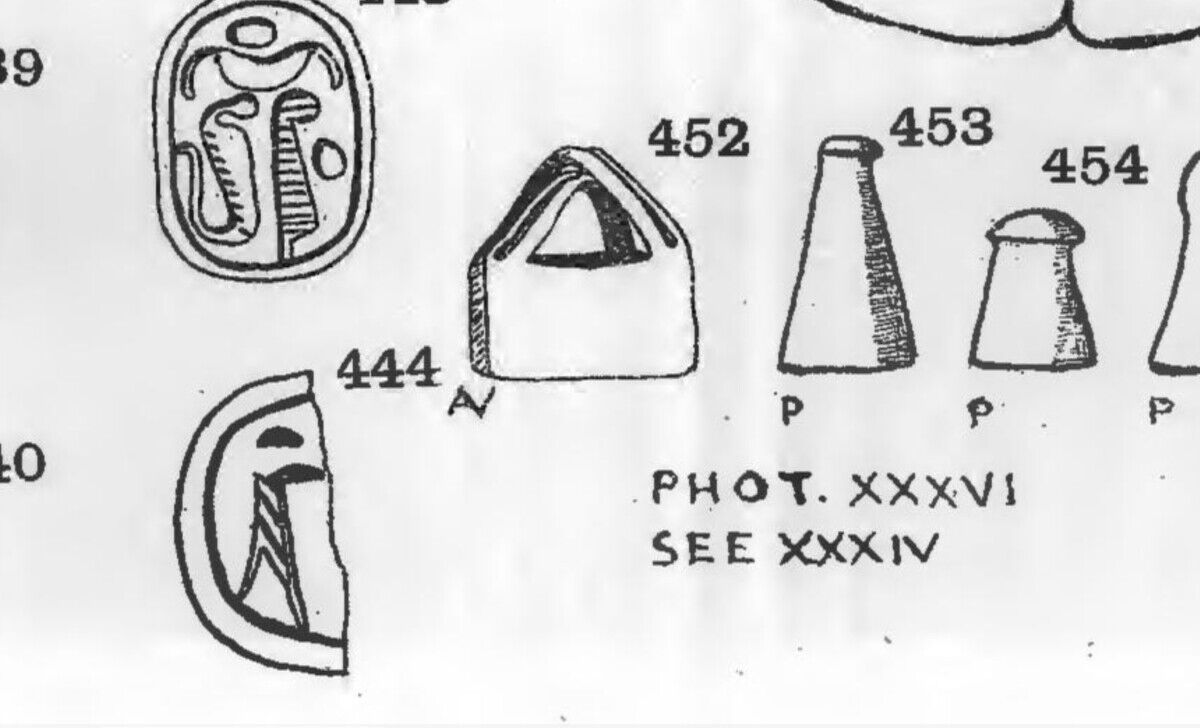

The graphic on page 244 in Golani’s text (above, right) shows four examples of “prototypes” of the Phoenician basket pendants found in the land of Israel from the 11th to 10th centuries b.c.e. Given that Phoenician culture likely evolved from Canaanite culture, it makes sense that similar basket pendants or prototypes were found from an earlier period in some areas still inhabited by Canaanites. Yet the prototype examples differ from the Ophel Basket Pendant even more than the later Phoenician examples. Two examples found in Beth Shean (published in the “Four Canaanite Temples of Beth-Shan,” by Alan Rowe in 1940) were two to three times the size of the Ophel pendant. They were also hollow on the inside; one even contained a scaraboid. The other prototype example discovered in Flinders Petrie’s excavations at Tell el-Farah (South) was also a hollow basket (Petrie, 1930, Beth-Pelet I, below).

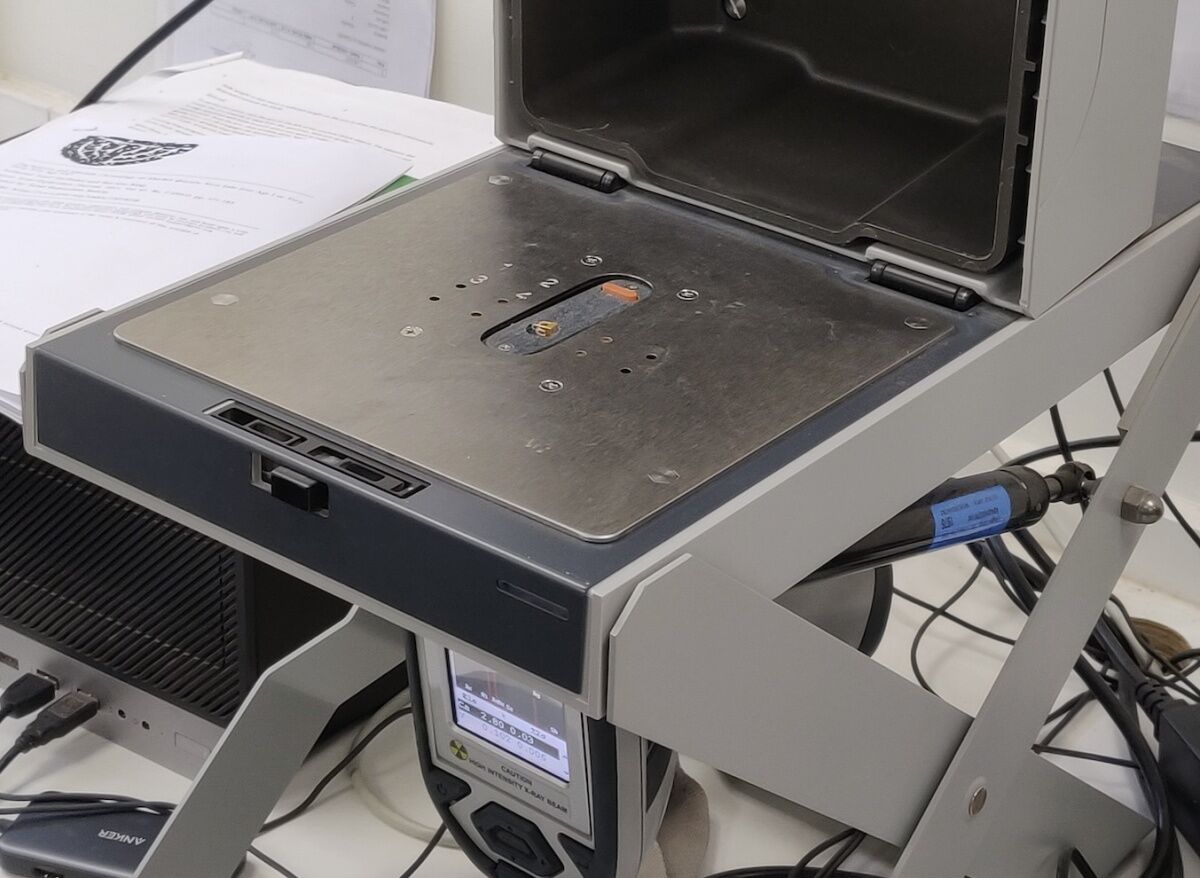

I took the artifact to Prof. Naama Yahalom-Mack, excavator of the northern Israel site of Abel Beth Maacah and head of the metallurgy lab at the Institute of Archaeology at Hebrew University, to discover the metal composition of the pendant. She ran three composition tests using the xlr machine, confirming that the pendant was electrum—an alloy of gold and silver (Au 63 percent, Ag 32 percent, Cu 5 percent, plus trace elements). This test confirmed the Ophel Basket Pendant to be the earliest “gold” artifact ever discovered in an archaeological excavation in Jerusalem to date. Electrum is a naturally occurring alloy; however, the high copper content means this is probably an artificial electrum alloy, which was likely combined with the gold and silver to obtain the desired color. Electrum is also a harder metal than pure gold, which provides greater durability for jewelry.

Soon thereafter, I met with Dr. Amir Golani at the Israel Antiquities Authority offices in Jerusalem to inspect the pendant. He was immediately amazed by the craftsmanship. “This is really good craftsmanship,” he told me. “I mean, it is really good craftsmanship, in terms of the goldsmith’s work himself. This is very good.” He then noted that it was indeed slightly different from the other later examples from Phoenician sites (shorter base cube, no pyramidal structure of granules, a higher level of craftsmanship in hiding joinery with gold strand). Nevertheless, he believed it was certainly of Phoenician origin and design. Golani also noted that since jewelry almost always reflects the ideas, cultures or motifs of the wearer, it acts as a cultural marker for a Phoenician presence in Jerusalem.

A Tribute to Dr. Eilat Mazar

Following the example of Dr. Eilat Mazar, it is impossible not to consult the biblical text for a window into the larger historical setting for the location, date and appearance of the Ophel Electrum Basket Pendant in Jerusalem.

Based on typology, the box pendant is clearly Phoenician and likely worn by a Phoenician. The pendant is dated by archaeological context to the early Iron iia (an archaeological period typically associated with the 10th-century b.c.e.). Finally, it was found in Jerusalem, specifically on the Ophel, a region north of the City of David, where monumental buildings were discovered.

The archaeological evidence alone points to a Phoenician presence in Jerusalem’s royal quarter during the 10th century b.c.e.

Pair this archaeological evidence with the Bible, and this tiny artifact resurrects the biblical history of the golden age in ancient Israel. It recalls the time of the united monarchy when Israel and Judah were unified under a single king ruling from Jerusalem. It tells of the time when Phoenicians of the Lebanese coast partnered with this king in his most important building projects in the capital city. 1 Kings 5:1 states, “And Hiram King of Tyre sent his servants unto Solomon: For he had heard that they had anointed him king in the room of his father: for Hiram was ever a lover of David.”

We now have the strongest archaeological evidence yet that Phoenician “servants” were indeed sent to Jerusalem in the 10th century b.c.e.

Sadly, Eilat is not here to witness the announcement of this discovery that was made as a result of her efforts. Eilat was not only an expert on Jerusalem, but also a Phoenician specialist. This was the focus of her Ph.D. dissertation at Hebrew University. Outside of Jerusalem, the only other excavation she directed was at the Phoenician city of Achziv on Israel’s northern coast. Whether it be the proto-Aeolic Phoenician-style capital found on her Ophel excavations or the Phoenician-style ivory inlay found on her excavations in the City of David, Eilat always drew attention to evidence of the Phoenician impact on Jerusalem. These were evidence of the Phoenician cultural influence in Jerusalem. However, jewelry is a personal item that expresses not only cultural influence but the actual personal identity of the wearer.

Thus today, at the opening of the ‘King David and Solomon Discovered’ exhibit and in honor of Dr. Eilat Mazar, we announce the discovery of the Ophel Electrum Basket Pendant, the best evidence so far that Phoenicians themselves were present in Jerusalem during the 10th century b.c.e, around the time of King Solomon.