The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?

The biblical account of Israel’s conquest of the Promised Land (recorded primarily in the book of Joshua) is full of action and drama. But how much truth is there to the account? This question has been fiercely debated by Bible maximalists and minimalists for centuries.

According to a literal reading of internal biblical chronology, the Israelites began their invasion of Canaan around 1400 b.c.e. Israel’s subjugation of the Promised Land occurred in three phases over a time span of several decades, on into the 14th century.

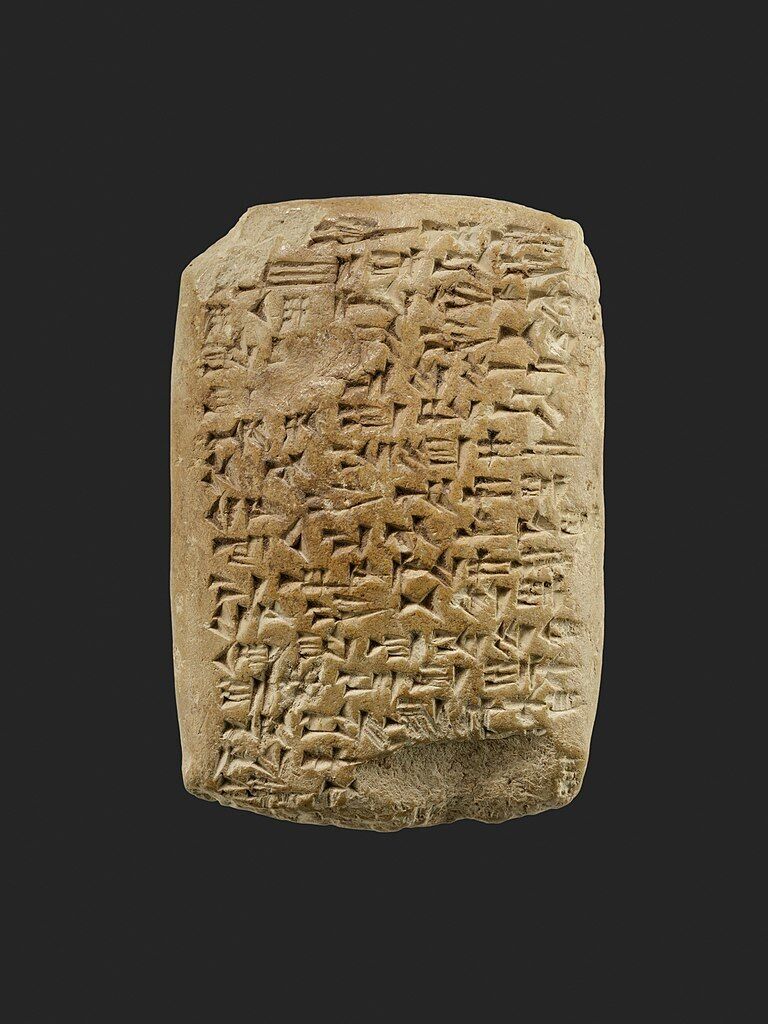

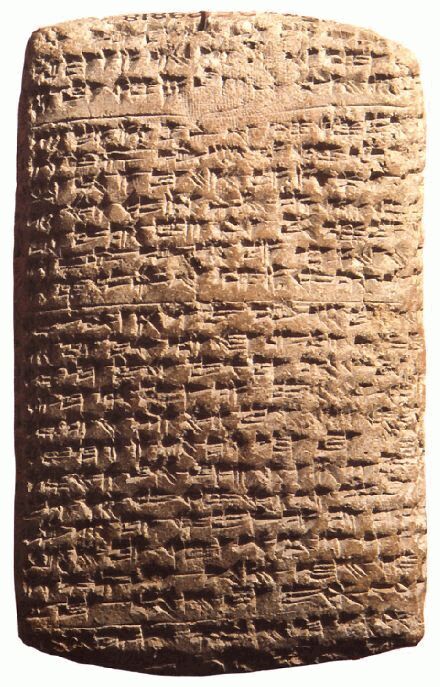

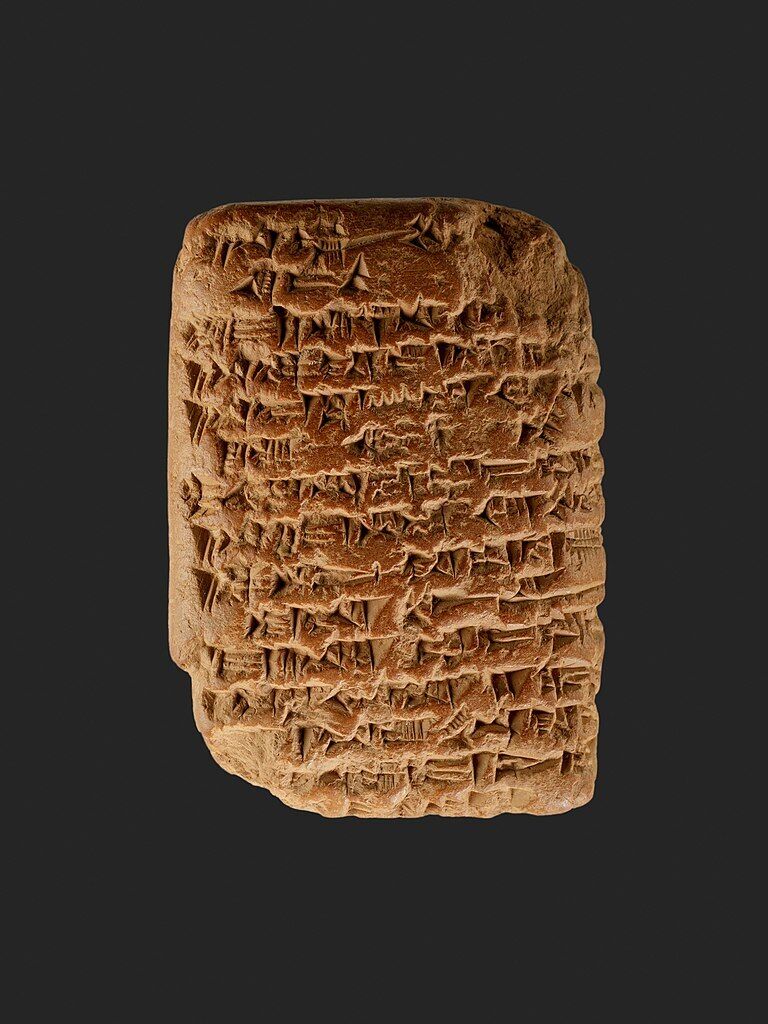

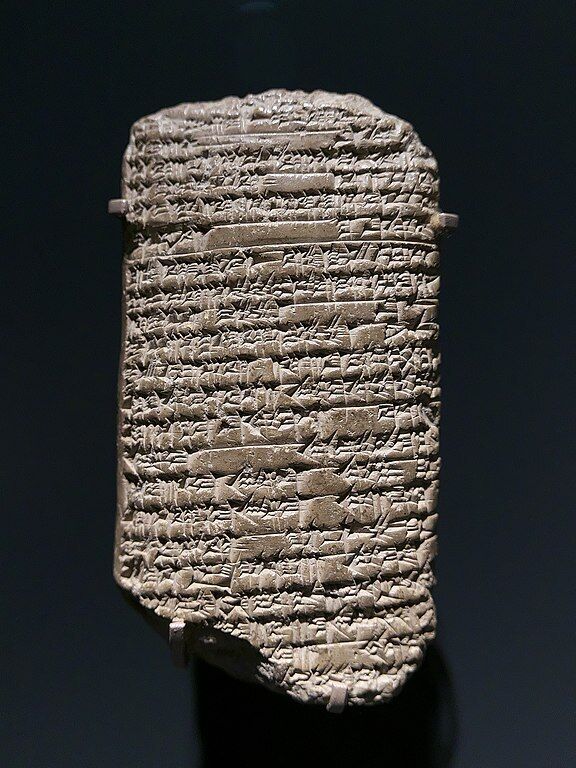

Over the last 150 years, a trove of literally hundreds of 14th-century b.c.e. clay tablets have been discovered in Egypt. Known as the “Amarna Letters,” many of these tablets are inscribed with text written by several different regional Canaanite rulers expressing consternation and even terror at the fact that “all the lands” were being overrun by a mysterious people they called the Habiru.

This raises the question: Who were the Habiru? Could the Amarna Letters represent eye-witness accounts of the Israelite conquest of Canaan?

The Amarna Letters

The small, blockish clay tablets are named after the location of their discovery in Tel el-Amarna, a major Egyptian city of the 14th century b.c.e. These letters constitute foreign correspondence primarily from the kings (or “mayors”) of the Levant—leaders of city-states in the modern-day territories of Israel, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria—to the pharaoh of Egypt, who generally controlled Canaan at the time.

Given that the administrative center of Amarna is known to have been abandoned at the end of Akhenaten’s reign, around 1335 b.c.e. (according to low chronology; two to three decades earlier, according to high), the Amarna Letters archived inside the city date to the decades prior—specifically, to the reigns of pharaohs Amenhotep iii and his son, Akhenaten. Over 300 tablets were found at el-Amarna in 1887; since then, more have been discovered, bringing the total number of letters to 382.

Almost all the tablets are from Canaanite rulers, with a handful from Mesopotamia and beyond. For reference purposes, the tablets are registered from EA 1 to EA 382 (EA standing for “el-Amarna”) in counter-clockwise geographic order, generally from north to south. The letters cover a broad range of diplomatic subjects.

The letters from the kings of the southern Levant have garnered the most attention. This is because they identify significant tumult arising with a distinct people in the early 14th century. The letters identify this group by the name Habiru and describe them conquering Canaanite territories en masse.

The messages from the various regional Canaanite leaders to Egypt’s pharaoh are filled with desperate pleas for help. Tablet EA 286 is a plea from Abdi-Heba, the mayor of Jerusalem: “Message of Abdi-Heba, your servant. … May the king [Egypt’s pharaoh] provide for his land! All the lands of the king, my lord, have deserted. … Lost are all the mayors; there is not a mayor remaining to the king, my lord. … The king has no lands. That Habiru has plundered all the lands of the king. If there are archers this year, the lands of the king, my lord, will remain.”

EA 299 was written by Yapahu, the ruler of Gezer, a Canaanite city situated west of Jerusalem in the foothills of the Judean mountains: “To the king, my lord … [s]ince the Habiru are stronger than we, may the king, my lord, give me his help, and may the king, my lord, get me away from the Habiru lest the Habiru destroy us.”

In EA 288, Jerusalem’s mayor once again beseeches the pharaoh. Note the description of the far-reaching extent of the Habiru conquests: “May the king give thought to his land; the land of the king is lost. All of it has attacked me. … I am situated like a ship in the midst of the sea …. [N]ow the Habiru have taken the very cities of the king. Not a single mayor remains to the king, my lord; all are lost” (emphasis added).

The Habiru invasion evidently was not localized to a handful of cities. According to the mayor of Jerusalem, these people conquered virtually the entire region—and during the very period of time in which Bible chronology shows that the Hebrews invaded.

What about this name given to the invaders?

Is Habiru the Same as Hebrew?

There has been significant debate about the identity of these Habiru (also commonly transliterated as Hapiru or ‘Apiru).

The names certainly look, and sound, similar to the name “Hebrew.” There is also a close match with the root of the name Hebrew—namely, ‘Abar. And the interchangeability of “b” and “p” in the name is readily explained by the fact that these sounds are known as “bilabial stops,” used interchangeably across different languages. (Consider, for example, the words absorb and absorption in English.) It’s why Arabic only has the letter “b,” which is used dually to represent the “p” sound. It’s also why, conversely, the New Zealand Maori language only has a letter “p,” used dually to represent “b” sounds. Interestingly, in the context of the name Habiru/Hapiru/‘Apiru, the word “Hebrew” in the Maori Bible is actually rendered almost exactly the same, as Hiperu.

If these were indeed the biblical Israelites, why didn’t the Canaanite leaders simply use this term? Actually, the collective noun Hebrews is used more often in the Bible to this point than the term Israelites. The term Hebrews, or one of its related forms, is used 22 times—compared with just twice for “Israelites.” (The literal terminology most commonly used in the Bible is the longer title “children of Israel.” That the Canaanites would prefer “Hebrews” over “children of Israel” is hardly surprising.)

Skeptics of the view that the Habiru should be associated with the biblical Hebrews/Israelites note that individuals with the title Habiru are not only referenced as living in Canaan but also in faraway Mesopotamia (though the bulk of the references do pertain to people living in the Levant). How to explain the presence of Habiru in these far eastern regions? Actually, the first biblical use of the term is to describe the Ur-born “Abram the Hebrew” (Genesis 14:13). This verse implies that the term was being used (and even originated?) in faraway Mesopotamia.

Note also the next biblical reference to the term: Joseph was likewise identified by officials in Egypt as “a Hebrew” (Genesis 39:14, 17; 41:12). Taken together, these verses suggest that the term “Hebrew” was the favored foreign appellation for this people—an already long-established term, with roots in Mesopotamia.

Some scholars speculate that the term Habiru began as a social category and turned into an ethnic one, theorizing that it may have encapsulated a broad range of then-nomadic peoples that included the Israelites (such as the Midianites, Kenites, Shutu, etc). Even this wider appellation would not be contrary to the biblical account given that Abraham—as a “Hebrew”—was father of the Midianites, Ishmaelites, etc (Genesis 25:1-4). Technically, much of the Arab world could be called “Hebrew.”

Yet while some theorize that the term may have evolved from a social reference to an ethnic one, the Bible says the opposite. Genesis 11:14 shows the name Hebrew (עברי) is a derivative of Eber (עבר), Abraham’s ancestor. The Bible clearly infers that the title began as an ethnic one rather than a social one.

Of course, it’s true that this appellation has been most strongly attached to the Israelites in the Bible. And it was Israel, after all, that continued to speak the “Hebrew” language. Suffice it to say that references to “Habiru” in various distant locations throughout various points of the second millennium b.c.e. in no way diminish the association with the Israelites or the Bible. Just the opposite: The predominance of the term Habiru around Israelite-occupied areas directly parallels the use of the term Hebrews in the Bible in predominantly referring to the Israelite people.

Just ‘Ragtag’ Mercenaries?

Some academics dismiss the Habiru as insignificant brigands or mercenaries. In The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts, Prof. Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman describe the Habiru as “outlaws or brigands” and as “soldiers for hire.” The authors note, “In one case they are even reported to be present in Egypt itself as hired laborers working on government building projects.”

Finkelstein and Silberman allow that “[i]t is possible that the phenomenon of the Apiru may have been remembered in later centuries and thus incorporated into the biblical narratives.” Still, they describe the “ragtag Apiru bands” as being more akin to the “outlaw chief David and his band of mighty men roaming in the Hebron hills and the Judean desert.”

A belief that the Habiru were a largely insignificant, ragtag group of brigands that occasionally pilfered Canaanite towns and incited domestic rebellions is relatively common. Yet it stands in stark contrast to the words of the Canaanite kings who witnessed the Habiru in person!

What was it that the Canaanite mayors wrote to the pharaoh? “All the lands of the king, my lord, have deserted.” “Lost are all the mayors.” “The king has no lands.” “The Habiru have plundered all the lands of the king.” “The Habiru are stronger than we.” “Lest the Habiru destroy us.” “The land of the king is lost.” “The Habiru have taken the very cities of the [pharaoh].” “All are lost.”

Were the Habiru merely pesky rogues and gangsters? Surely not.

But beyond a general comparison of the Habiru with the biblical Hebrews and their conquest of Canaan, does a closer analysis of the acts of the Habiru described within the Amarna Letters correspond specifically with the biblical description of the Hebrew conquest of the Promised Land?

In short: Absolutely!

Conquest, Territory By Territory

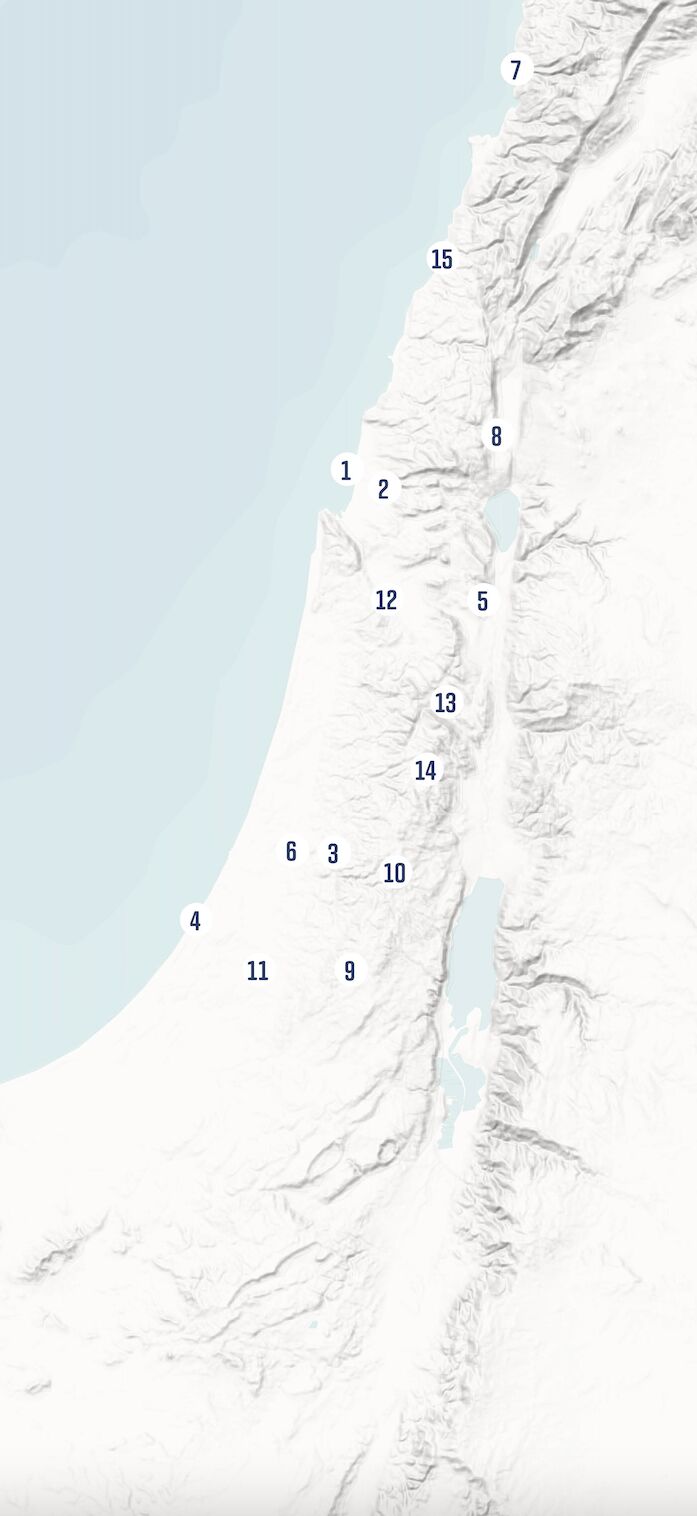

Below is a list of content from the Amarna Letters, arranged alphabetically by city/region (with either the letter having come from the city in question, or the city/region being described in letters from rulers of other cities). A brief summary is given for each as described in the Amarna Letters (sometimes contained in more than one letter—EA citations provided) and then compared with the biblical account. (A map is provided for reference to the regions described.)

1. Acco

- Amarna: Acco helps the Canaanite war effort against the Habiru but apparently later sides with them and is allowed favor (EA 88, 366).

- Bible: The Israelites fail to drive out the inhabitants of Acco, allowing them to remain in the land (Judges 1:31).

2. Achshaph

- Amarna: The king of Achshaph comes to fight in coalition against the Habiru (EA 366).

- Bible: The king of Achshaph joins a coalition to fight a staged battle against the Israelites, but is killed (Joshua 11:1; 12:20).

3. Aijalon

- Amarna: The enemy has control in the countryside of Aijalon (EA 287).

- Bible: Aijalon features in a major staged land battle, where Israel conquers “Aijalon with the open land about it” (Joshua 10:12; 21:24).

4. Ashkelon

- Amarna: The land of Ashkelon is now in league with the enemy (EA 287).

- Bible: Ashkelon is taken by the Israelites (Judges 1:18).

5. Beth-Shean

- Amarna: A strong garrison is prepared and stationed at Beth-Shean—no indication that it is conquered (EA 289).

- Bible: The Israelites fret about iron chariots stationed at Beth-Shean and fail to drive out the inhabitants (Joshua 17:16; Judges 1:27).

6. Gezer

- Amarna: The king of Gezer fights against the Habiru, but it seems there is a movement by his own people (including his own brother) against him, who appear to overthrow him and end up aiding the enemy (EA 271, 287, 298, 299).

- Bible: The king of Gezer is killed, but for some untold reason the Canaanites of this area are allowed to remain and give tribute to Israel (Joshua 10:33; 12:12; 16:10).

7. Gebal (Byblos)

- Amarna: The king of Gebal worries about the potential of the Habiru attacking the city. However, there is no evidence that it was (EA 68, 73, 74, 76, 77, 88, 90, 121, 188).

- Bible: Joshua informs the Israelites that the northern lands, including Gebal, still need to be conquered (Joshua 13:5). However, there is no statement that they ever were.

8. Hazor

- Amarna: The king of Tyre, writing about neighboring Sidon, notes that Hazor is turned over to the Habiru (EA 148, 228).

- Bible: Joshua conquers Hazor and chases the enemy all the way to Sidon (Joshua 11:1-13).

9. Hebron

- Amarna: Hebron, in league with Jerusalem and Lachish, is at war with the Habiru (EA 271, 284, 366).

- Bible: The king of Hebron, in league with the king of Jerusalem and the king of Lachish, attends a staged land battle where all are defeated (Joshua 10:5). The territory of Hebron is later attacked and conquered (verses 33, 36-37).

10. Jerusalem

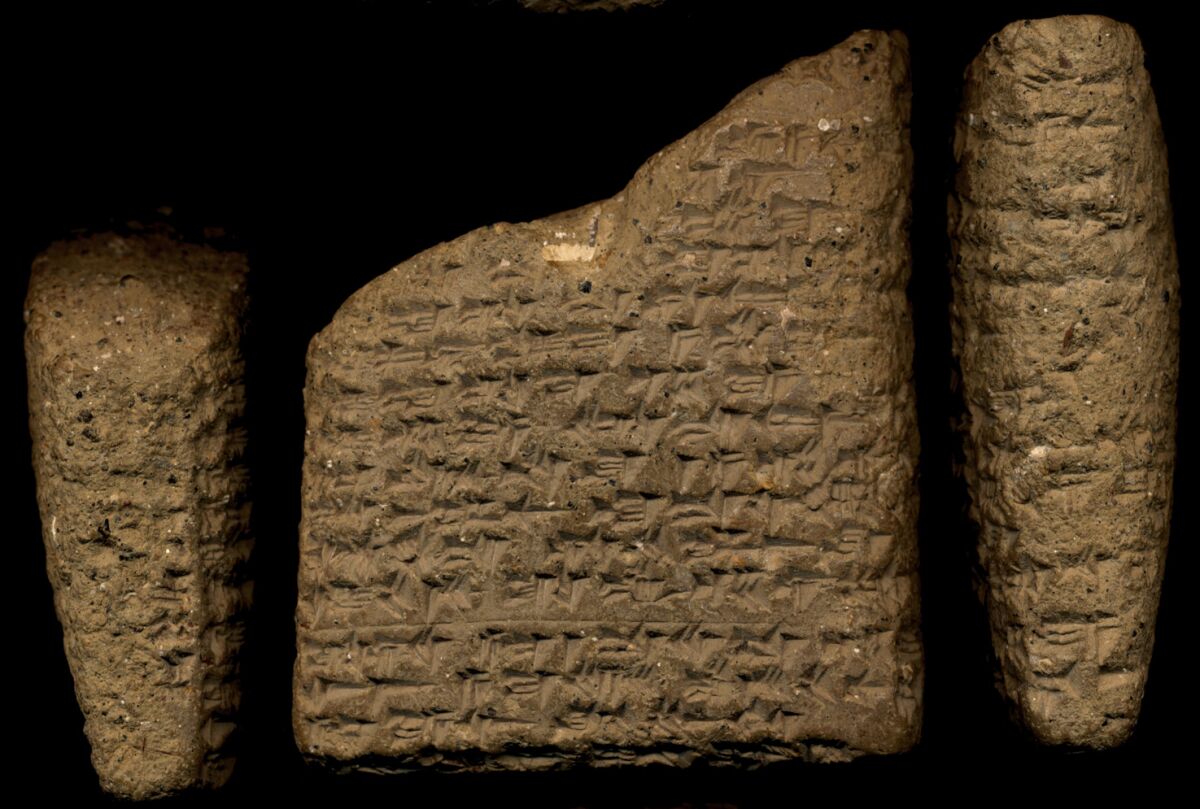

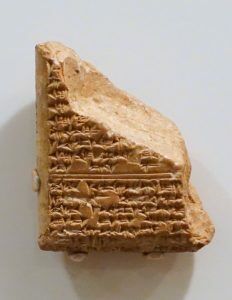

- Amarna: Jerusalem and its territory is apparently one of the last remaining places to be attacked (EA 286, 287, 288). Also note a similar-style, burned Canaanite tablet fragment discovered in Dr. Eilat Mazar’s Jerusalem excavations (speculated to be the work of the same scribe of Abdi-Heba’s letters, thus dating to the same period).

- Bible: Jerusalem is one of the last places to be attacked and conquered (Judges 1:8). When the city is eventually conquered at the start of the judges period, it is burned (same verse).

11. Lachish

- Amarna: The Habiru killed a leader of Lachish and gained control of the city (EA 287, 288, 329, 330, 333).

- Bible: The Israelites killed the king of Lachish in a separate land battle and later conquered the city (Joshua 10:23-26, 31-32).

12. Megiddo

- Amarna: Megiddo is attacked and defeated by a group allied with the Habiru (EA 243, 244, 246).

- Bible: The king of Megiddo is killed, but Canaanites maintain hold of the city (Joshua 12:21; Judges 1:27).

13. Shechem

- Amarna: The Habiru are handed the land of Shechem by its ruler, Labayu (EA 289).

- Bible: There is no description of an attack on Shechem, yet the Israelites are described as having full control over it (Joshua 24:1).

14. Shiloh

- Amarna: The Habiru attacked Shiloh (EA 288).

- Bible: There is no description of an attack on Shiloh, but the Israelites evidently acquired it and established it as the site of the tabernacle (Joshua 18:1).

15. Sidon

- Amarna: The king of Sidon writes that his surrounding cities have joined themselves to the Habiru (EA 144).

-

Bible: While battle did reach as far north as the borders of Sidon, the Canaanite inhabitants remained in that city (Joshua 11:8; Judges 1:31).

This small clay tablet fragment was found in 2009 during Dr. Eilat Mazar’s excavations of Jerusalem’s Ophel. It is believed to have represented an archival copy of Amarna correspondence. For whatever reason, it shows evidence of having been burned in a fire. Judges 1:8 states that toward the end of the conquest period, the “children of Judah fought against Jerusalem, and took it, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and set the city on fire.” Eilat Mazar

All Just Coincidence?

It could be possible to dismiss some of these city-by-city comparisons as coincidences. But every single one? And again, the events recorded in the Amarna Letters happened during the same chronological window described in the Bible for Israel’s conquest of Canaan.

If the debate here revolved solely around the semantics of the terms Habiru and Hebrew (as it often does), it would be harder to draw a clear and unequivocal conclusion. But the semantic similarities, combined with the timing, as well as the city-specific details described in the Amarna Letters, align precisely with Israel’s conquest of Canaan as recorded in the Bible, thus by weight of evidence showing they are describing the same event: Israel’s conquest of the Promised Land!

Sidebar: ‘Men of Judah’ in the Amarna Letters?

One of the Amarna Letters, EA 39, contains peculiar references to “ameluti Ia-u-du” and “ameluti tsabe Ia-u-du.” The spelling of Ia-u-du is identical to that of later Assyrian cuneiform inscriptions referring to Judah. If this is a reference to the Israelite tribe, then the above two passages translate to “men of Judah” and “soldiers of Judah.”

Prof. Morris Jastrow Jr. (1861–1921) first made this observation in his 1893 article “‘The Men of Judah’ in the El-Amarna Tablets.” Some small debate circulated at the time regarding the nature and correct interpretation of the inscription. One of the primary issues was that the inscription was related to territory in the extreme north of Canaan (midwest Syria), perhaps around the region of Tunip—a peculiar place to find “men of Judah.” There was some dissent that this referred instead to a slightly different but similar sounding word, meaning “they have witnessed.” Jastrow, in his paper, refuted this by showing that the context identifies Ia-u-du as a proper name for a clan or group.

Still, the question remained: What would a southern tribe be doing so far north? Indeed, this tribe is known to have settled in the southern part of Canaan. But the Israelites were to conquer the Promised Land together, as a unit (e.g. Numbers 32). Further, the territory of Israel was intended to expand as far north as Hamath in Syria—a location just east of Tunip (Numbers 34:8).

A peculiar, much-debated northern link to Judah is found in 2 Kings 14:28, which states that the territory of “Damascus, and Hamath … belonged to Judah” (King James Version). This was while the northern kingdom of Israel had long been divided from the southern kingdom of Judah—yet the tribe of Judah apparently somehow held an outpost north of Israel. There is also another peculiar reference to a Judahite-connected territory in Syria on an Assyrian inscription of Tiglath-Pileser iii (see our article here for more detail.) As such, in light of these additional references, the presence of “men of Judah” in the far north—in Syria—may not be as unusual as it at first seems.

Unfortunately, the section of EA 39 bearing the text Ia-u-du isn’t in ideal condition, leaving the question open to debate. Since Jastrow’s work, Norwegian linguist Jørgen Knudtzon’s analysis, categorization and translation of the Amarna Letters has been the go-to standard, particularly his two-volume work Die El-Amarna-Tafeln (1907 and 1915). Knudtzon, for his part, translated this word differently, as “s[u]-u-du”—positing it as a Syrian fortress called Sudu.

Nevertheless, the translation Ia-u-du remains an intriguing possibility. And it’s not the only such biblical link identified by Jastrow: He further highlighted two clan names mentioned in the Amarna correspondence, Milkil and Habiri, identifying them as two clans of the tribe of Asher, Malkiel and Heber (Genesis 46:17; Numbers 26:45; 1 Chronicles 7:31). These names were mentioned together in correspondence from the Canaanite leader of Jerusalem, Abdi-Heba, to the pharaoh.

Article updated 24/7/24.

Read More: