First-Ever Inscription Found in Israel With Name of Persian King Darius the Great

Note: This discovery has since been revealed to be a modern inscription, and its identification has been retracted by the Israel Antiquities Authority. See our follow-up article and podcast on the subject here and here. The below remains archived for reference.

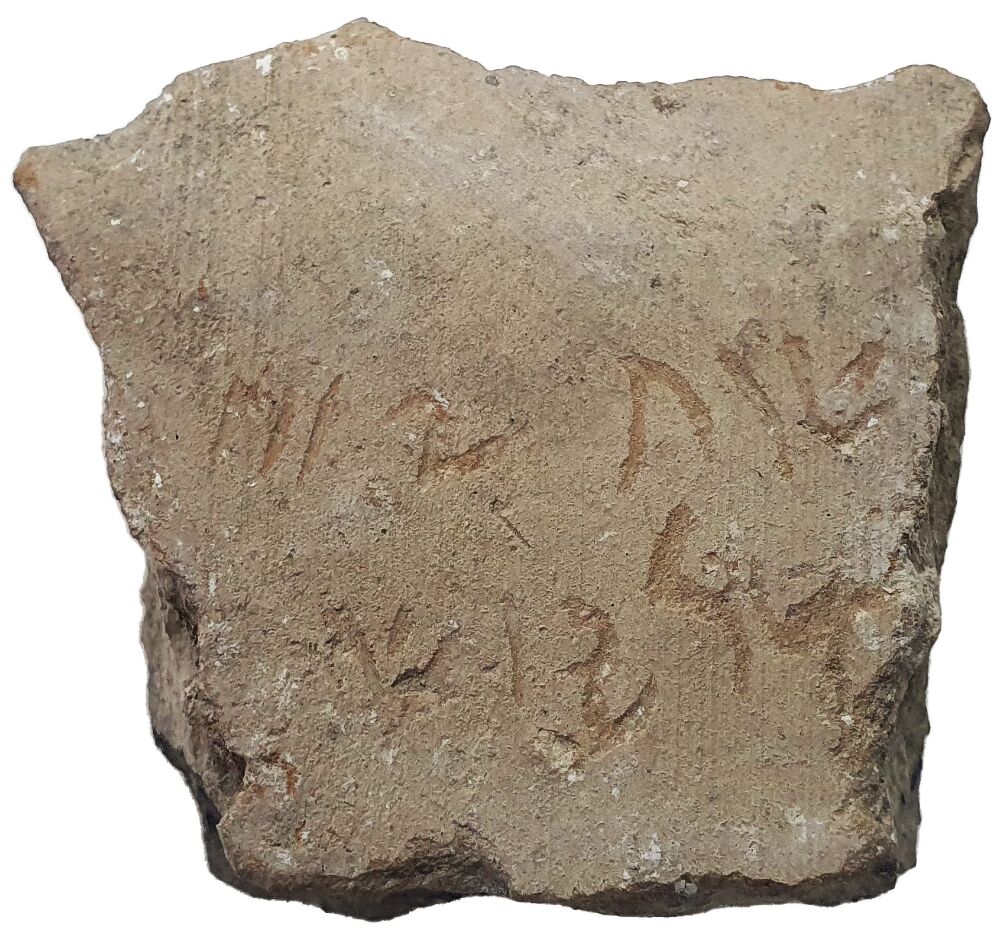

While touring Tel Lachish last December, visitors Yakov Ashkenazi and his friend Eylon Levy stumbled across a pottery sherd with an inscription etched across it. After reporting it to the Israel Antiquities Authority (iaa), and following research of the sherd by epigrapher Dr. Haggai Misgav (Hebrew University) and Saar Ganor (iaa), the potsherd inscription—known as an ostracon—was revealed to be the first-ever inscription found in Israel bearing the name of the famed Persian king, Darius the Great. It is also one of the oldest Persian administrative inscriptions ever found in Israel.

The 2,500-year-old Aramaic inscription reads, “Year 24 of Darius,” thus dating it to 498/7 b.c.e. Darius the Great (who ruled from 522 to 486 b.c.e.) is not the famed ruler of the same name in Daniel 6 (Darius the Mede); he is, however, the Darius mentioned several times throughout the book of Ezra, who was favorable to the Jews in their reconstruction efforts of the temple. Darius the Great is also the father of Xerxes (rendered as “Ahasuerus,” or “Achashverosh,” in the Bible), who was the famous Persian king of the book of Esther—thus making this Darius Esther’s father-in-law.

Ezra 5-6 takes place entirely during the early years of Darius’s reign. It records how the prophets Haggai and Zechariah encouraged Zerubbabel to continue working on the temple after work had been halted. Seeing this renewed effort, the Persian governor Tattenai (whose existence has been proven outside the Bible) wrote to Darius informing him of the work of the returned Jews. Darius subsequently issued a new decree that demanded nobody should stop the work. “Let the governor of the Jews and the elders of the Jews build this house of God in its place,” wrote Darius to Tattenai (Ezra 6:7). The temple was finally completed in the sixth year of Darius, 18 years before this recently discovered ostracon was inscribed.

Tel Lachish is an important site located roughly 40 kilometers (25 miles) southwest of Jerusalem. It was regarded as Judah’s “second city” after Jerusalem during the time of the biblical monarchy, and continued to function as an important site through the ensuing Persian period. A British archaeological expedition to the site in the 1930s discovered an “elaborate administrative building from the Persian period, built on top of the podium of the destroyed palace-fort of the Judean kings,” researchers Ganor and Misgav noted in a statement to the press. The large residence included “elaborate halls and courtyards with a majestic columned portico entrance in Persian style.”

The researchers believe that the ostracon, discovered in the vicinity of this structure, represented an administrative note from a storeroom official relating to the dispatchment of goods or collection of taxes. Lachish, at this time, served as a location responsible for the collection of taxes for the king’s treasuries. The site constituted part of an overall satrapy known both in the Bible and in inscriptions as the territory “beyond the River” (i.e. Ezra 6:6-13). The Bible also states that this city, Lachish, was populated during this fifth century b.c.e. (Nehemiah 11:30).

The new inscription will be published in the Israel Antiquities Authority journal ‘Atiqot, Vol. 110: “The Ancient Written Wor(l)d.” For more on the subject of Esther and other biblical Persian-period discoveries, see our articles “Nehemiah: A Man and a Momentous Wall,” and “The Dead Sea Scrolls Don’t Include the Book of Esther—or Do They?”