A Japanese Prince, Herbert Armstrong, and an Unlikely Partnership in Biblical Archaeology

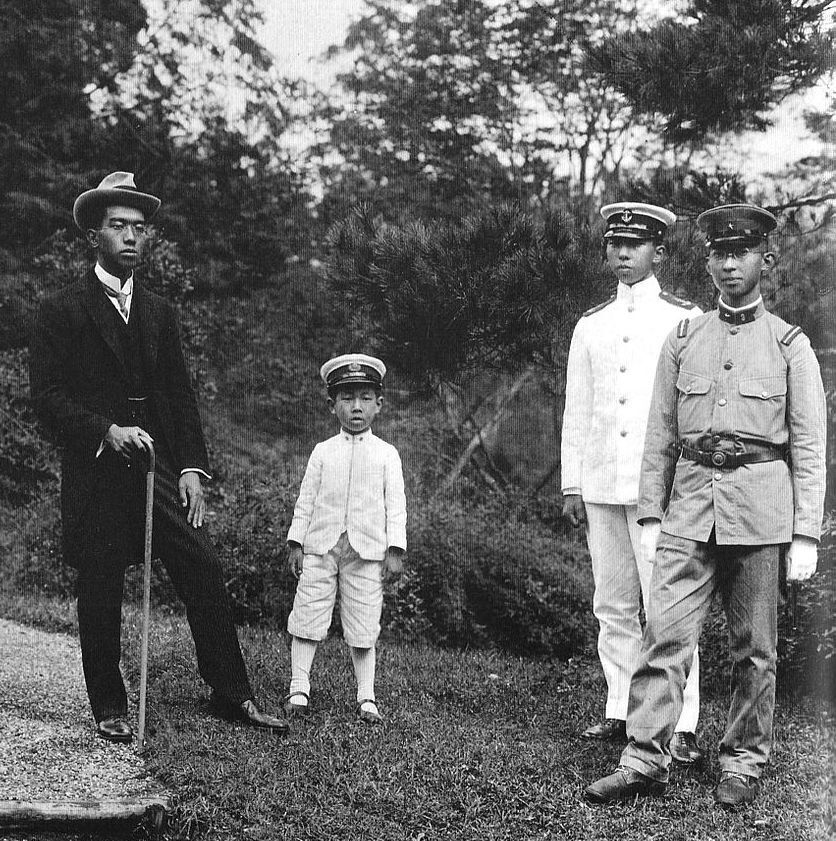

Prince Takahito Mikasa (1915–2016), the younger brother of Japan’s late Emperor Hirohito, lived an accomplished life. He fought in World War ii, spoke at least three languages, and taught history at a college. He was a noted scholar and became an accomplished ice dancer. But what may be one of the most defining aspects of his legacy was his outreaches to the Middle East—especially Israel. It was through these that he formed a remarkable biblical archaeology partnership, and friendship, with our namesake Herbert W. Armstrong.

Prince Mikasa was a cavalry officer for the Japanese invasion of China in World War ii. He went there to serve his empire, but he became disillusioned with war after seeing how cruelly the Japanese troops were treating the Chinese. In China, he “had completely lost faith in the ‘sacred war’ and the only thing I wanted was peace,” he wrote in 1956. Seeing “the abominable atrocities committed against the innocent Chinese people” made him disillusioned with the country he belonged to. He even contemplated forfeiting his royal title and becoming a commoner.

Escapism led him to scholastics. He was originally interested in European civilization, but in studying the origins of Christianity, Prince Mikasa was introduced to the study of the Jews. This changed his life. According to Arnold Wolf, an American rabbi who heard the prince speak at a Hanukkah reception in Tokyo, Prince Mikasa “discovered one supreme fact; that the Jews were the key to Western civilization.” The prince saw that Jews had heritage both in Western and Eastern culture. He saw Jews as “the holy bridge … between East and West. Through understanding Judaism, the prince regained a sense of dignity as a member of his people; he was again proud to be Japanese.”

Prince Mikasa’s new love for the Jews spurred him to different ventures. He learned how to speak Hebrew fluently. He served as president of the Jerusalem conference for the International Association for the History of Religions in 1968. But the discipline he devoted himself most to was Middle Eastern archaeology. In 1954, he founded the Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan, one of the pioneering institutions to introduce Middle Eastern archaeology to Japanese scholarship. In 1956, he sponsored the first Japanese archaeological excavation in the Middle East at the site of Telul eth-Thalathat in Iraq. The prince himself was present for the groundbreaking ceremony.

The prince’s interest in archaeology was shared with a friend of his, Herbert W. Armstrong, late theologian and our institute’s namesake (who also had a close relationship with members of Japan’s Diet, or parliament, who affectionately called themselves his “sons”). Over the course of his world travels—including to Japan—Mr. Armstrong got to know Prince Mikasa well. This relationship between Mr. Armstrong and Prince Mikasa blossomed into special collaboration. In 1970, Mr. Armstrong and Prof. Benjamin Mazar of Hebrew University hosted an archaeological exhibition in Tokyo. In a May 29, 1973 co-worker letter, Mr. Armstrong announced the plans for an “Ambassador Institute of Biblical Research” operated jointly with the prince. (Those plans apparently never materialized.) Prince Mikasa supported Mr. Armstrong’s Ambassador College archaeological dig at Israel’s Tel Zeror.

Tel Zeror is an ancient city located in Israel’s north, on a trade route between the Mediterranean port of Dor and Samaria, the ancient capital of the northern kingdom of Israel. The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan had first started digging there in 1964, directed by the University of Tokyo’s Professor Emeritus Kiyoshi Ohata, with Prince Mikasa as one of the dig’s benefactors. Tel Zeror is actually composed of two tels (artificial mounds made up of various strata from ancient civilizations) located next to each other. The first stratum uncovered revealed a Medieval Muslim cemetery; further work revealed that the layers of occupation continued all the way to the Middle Bronze Age (circa 1950–1650 b.c.e.). The Society’s three seasons concluded in 1966. Their fourth, in 1974, was cosponsored by Ambassador College. This was one of two archaeological projects in Israel sponsored by Ambassador College; the other, more famously, was in Jerusalem in conjunction with Hebrew University and Prof. Benjamin Mazar (the decade-long Temple Mount “Big Dig”). The June 24, 1974 Worldwide News reported nine Ambassador students and one faculty supervisor to be sent to Tel Zeror for several weeks that summer, concluding on August 13.

Mr. Armstrong’s relationship with the people of Japan wasn’t just limited to Prince Mikasa. Through the course of his long life, Mr. Armstrong met with seven different Japanese prime ministers and was even given an audience with Emperor Hirohito himself. Ambassador College accepted Japanese students, including through sponsorship by Japan’s Ministry of Education. In 1973, Mr. Armstrong was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, then the second-highest honor the government could bestow on an individual.

Herbert Armstrong died in 1986. He may have died decades ago, but his legacy in Israel lives on. Today, the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology continues the legacy Mr. Armstrong established. We recently concluded a smaller dig on the Ophel in Jerusalem over the summer, and have future excavations in Jerusalem planned. We have also recently opened aiba’s new headquarters building in Jerusalem. As with Prince Mikasa, the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology believes the Jews’ ancient heritage can serve as a bridge—not only between Western civilization and the East, but for all of mankind.