Excavating the Ophel

It’s a running joke in the world of archaeology: The best finds are typically made on your final day of excavation, just as you’re about to pack up and head home. This is exactly what happened to us on the last day of excavation on the Ophel in 2018.

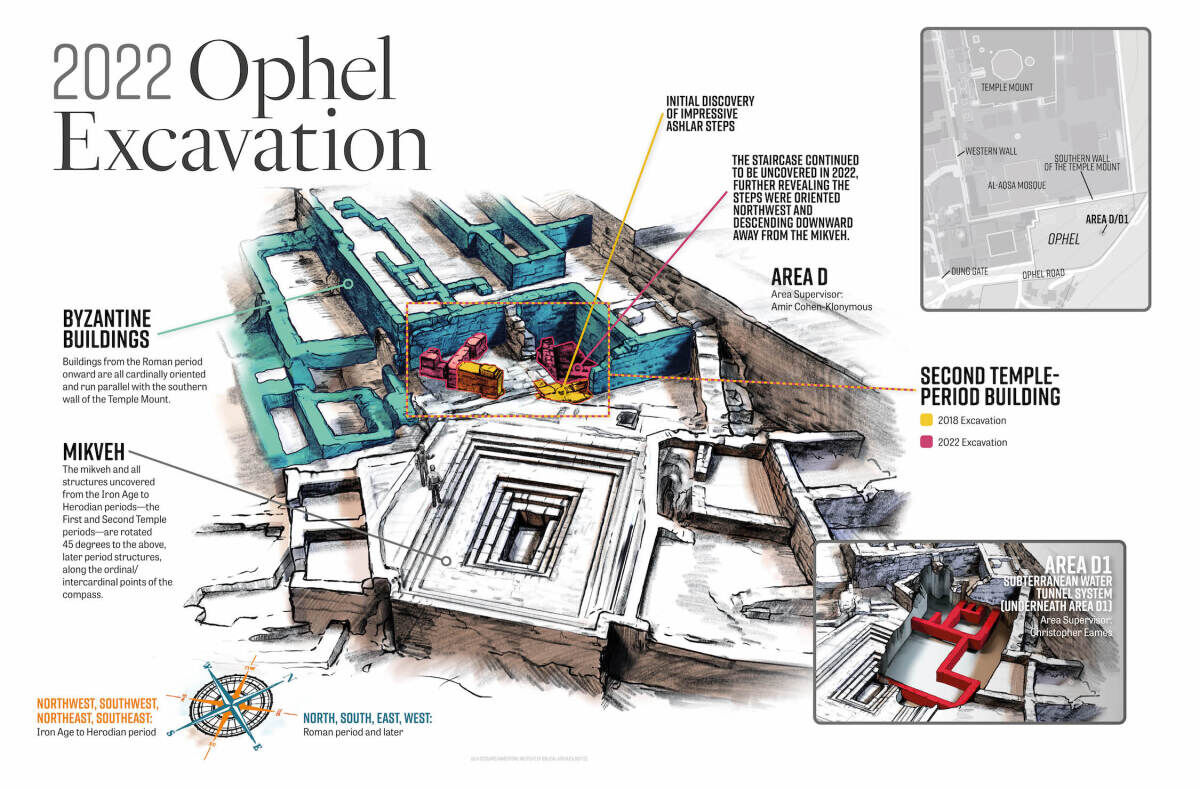

We were excavating with Dr. Eilat Mazar and archaeologist Amir Cohen-Klonymous, finishing up Phase 2c of the Ophel excavations. The day was spent removing material at the lowest level of a large Byzantine structure. In the final hours of excavation, we unexpectedly began to uncover a series of grand and immaculate Second Temple-period stone steps at the base of the structure.

We were excited and more than a little curious. Where did these magnificent steps lead? The size and design of the steps suggested they were part of an impressive Second Temple-period structure. How large was it? What was the building used for? How exactly did the steps relate to an existing series of water tunnels directly beneath (and connected to) this structure?

Dr. Mazar was pleased with what we accomplished in Phase 2c of the Ophel excavation, which included the unearthing of a large cache of Jewish Rebellion coins. But Phase 2c ended with a dramatic and intriguing discovery and a bunch of questions. (Great archaeological sites are like great restaurants; they leave you wanting more.)

In July, we returned to the Ophel to continue excavating—and to hopefully get some answers. Here’s an overview of where we excavated, the periods we excavated, and the questions we wanted to explore. It’s too early to reveal in detail what we found; the finds continue to be analyzed and documented. But we can tell you this: The latest phase of the Ophel excavation significantly expanded our understanding of the area and furnished a veritable treasure trove of fascinating and remarkable finds.

While we were excited to return to the Ophel, we were also a little sad, as this was our first excavation without Dr. Eilat Mazar. While we missed Eilat greatly, we were privileged to work under the direction of one of her friends and colleagues, Hebrew University archaeologist Prof. Uzi Leibner. Professor Leibner is the head of the Institute of Archaeology at Hebrew University and specializes in the Greek, Roman and Byzantine periods. He’s also a born teacher. On the dig, Prof. Leibner routinely took the time to explain to our students what they were uncovering, to solicit their thoughts, and to share his personal thoughts on the Second Temple-period structure that came more into focus every day.

We also dug alongside our good friend Amir Cohen-Klonymous. Amir was area supervisor over the upper area, containing the beautiful Herodian steps. The other area supervisor was our very own Christopher Eames, who oversaw the excavation of the subterranean tunnel network connected to the Second Temple-period structure above.

A Brief History

It is hard to overstate the importance, both archaeologically and historically, of the Ophel. Situated north of and adjacent to the City of David, the land was originally acquired (and likely partially developed) by King David (2 Samuel 24:18-25). When Solomon became king in the 10th century b.c.e., he commenced a massive northward expansion of the City of David.

On the Ophel, King Solomon constructed his impressive palace (which the Bible relates took 13 years to build), a massive royal armory (see 1 Kings 7), a series of fortification walls and gatehouses and, most notably in his northern expansion, the temple and its associated structures. The Bible says that subsequent kings of Judah (particularly Uzziah, then his son Jotham) added to Solomon’s royal complex (2 Chronicles 26:9; 27:1-6).

The Ophel was the seat of Israel’s (then Judah’s; following the separation of the united monarchy) government and religion for roughly 400 years, from the middle of the 10th century b.c.e. to Jerusalem’s destruction in 586 b.c.e. The area remained the nucleus of the Jews’ politics and religion throughout the Second Temple period, especially during the reign of Herod the Great, all the way up until Jerusalem’s 70 c.e. destruction.

Most of our archaeological work with Dr. Eilat Mazar on the Ophel focused primarily on the Iron Age period. However, before you can excavate Iron Age material, you have to excavate later periods that typically cover and obscure the earlier material. This was the case with the 2018 Ophel dig, where we excavated through Islamic and Byzantine period remains, before reaching earlier, Herodian and Hasmonean material.

The 2018 excavation was divided into two primary areas of excavation. The first was Area M, which consisted of a large cave. The material in this area was mainly Herodian and included the discovery of a Year 4 coin hoard (from the final year of the Jewish Revolt, 70 c.e.). This hoard remains one of the largest Year 4 coin assemblages ever discovered in Israel.

The second area of excavation was Area D. This area was situated adjacent northwest of a large mikveh (ritual bath), and included a large upper Byzantine structure, situated alongside what was identified by Dr. Mazar as the Byzantine “Monastery of the Virgins,” mentioned in classical texts. In 2013, we uncovered the Menorah Medallion gold hoard (one of the top three largest gold hoards ever discovered in Israel), in the southwest wing of this structure. Area D contains both Byzantine and Herodian-era remains.

This summer we continued to excavate Area D. The dig was divided into two main areas. The first area (supervised by Amir) contained the Byzantine structure and the Early Roman remains beneath. The second area (D1, supervised by Christopher) was a series of subterranean chambers and drainage tunnels made up of finely carved ashlar stones, most of which are situated below the Byzantine and Herodian structures.

The Mikveh

One of the most visible and iconic architectural features on the east side of the Ophel is the large four-way, stepped rectangular mikveh. This Second Temple-period feature was discovered during the 1980s by Meir Ben-Dov. It is evident that the Second Temple-period structure that is beginning to emerge orients toward this ritual pool. The network of tunnels connects directly to a drainage port at the base of the mikveh.

The orientation of the mikveh, as well as the entire structure, is noteworthy. The structures on the eastern edge of the Ophel, from the Roman period onward, are cardinally oriented—they run parallel with the southern wall of the Temple Mount. Interestingly, the structures we have uncovered from the Iron Age to Herodian periods—the first and second temple periods—are clearly rotated precisely 45 degrees, along the ordinal (or intercardinal) points of the compass.

The Second Temple-period structure now coming into focus, as well as the mikveh and underground tunnels, all fall into the latter category (illustration, page 14).

The mikveh remains somewhat of a mystery. The pool is not a standard single-direction ritual mikveh. Rather, it has steps on all four sides and more closely resembles the design of the (much larger) Pool of Siloam, south of the City of David. Is this significant? What does the mikveh’s unique design and large size tell us? (If you’re interested in learning more about this bath, read chapter i.7 of Dr. Eilat Mazar’s The Ophel Excavations to the South of the Temple Mount, 2009–2013, Final Reports Vol. II, by Asher Grossberg).

The mikveh’s design isn’t the only enigma. We know this site was extensively excavated in the 1970s under the direction of Professor Mazar and Ben-Dov. However, almost all of the original documentation for this area is missing. Without this information, we don’t know exactly what was originally found. The challenge is amplified by the fact that part of the remains, including at least part of the rectangular mikveh, were reconstructed following the 1970s excavation (covering up the original material). What did this area, particularly in and around the mikveh, look like before it was reconstructed? Would this offer clues to the function of the original building and the related below-ground system we are uncovering?

These are just some of the questions we were hoping to begin to answer.

The tunnels are another enigma that we’re trying to understand. We were already generally aware of the extent of these tunnels, as they have been investigated and drawn by the site architect. But until this excavation, they were largely filled with “fill” (earth), barely allowing passage, even on hands and knees. Why is there a series of bisecting tunnels and chambers underneath the area? What purpose did these serve?

There is some beautiful architecture in these tunnels—why? One thing we do know is that the subterranean structure was built from the ground up and supports the upper Second Temple-period building that stands above it. There seem to have been access points along the tunnels from various parts of the building above, certain of which remain inaccessible from above until further excavation. We know this subterranean network did not serve merely as the drainage system for the large mikveh and associated building. We also learned that there were several phases to the historic use of these tunnels.

For the first time, we excavated these fascinating tunnels to hopefully find out their exact purpose and extent. (And as with any subterranean fill within a water system, there is the promise of exciting discoveries that were quite literally “flushed” down into it!)

In order to retrieve the potentially rich finds that washed into this subterranean system, we both dry-sifted and wet-sifted all of the material removed from the tunnels. The dry-sifting (a process that separates out fine earth and larger stones, and enables sorting of the larger, more visible finds) took place on-site. The material was then sent to Mount Scopus to be wet-sifted by the Temple Mount Sifting Project, an experienced wet-sifting team run by Dr. Zachi Dvira.

Although we do not yet have a complete or detailed understanding of this Second Temple-period structure, we uncovered much more evidence revealing its monumental nature, including more large and impressive steps and walls.

The evidence suggests that the building, with its fine and grand architectural features (some of the finest Herodian architecture on this side of the Ophel), was directly related, in some form or other, to the function and use of the temple. One of the strongest proofs of this is the discovery in the area of numerous (more than a dozen so far) second temple purification baths.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6bsf40SVSS4

What was the nature of the relationship between this building and the temple? What was the structure used for exactly? We don’t have the answers to these questions—yet.

Biblical history provides some insight. The book of Nehemiah, for example, notes that the Ophel was the dwelling place of the Nethinim, the temple servants, at the time of the second temple (Nehemiah 3:26-31; 11:21).

2 Chronicles 27:3 also describes King Jotham’s temple-related building projects, together in context with the Ophel. Asher Grossberg (who wrote the chapter on the mikveh for Dr. Mazar’s Ophel Final Reports, Vol. II) notes a historical reference to a potentially similar, raised upper pool/mikveh relating to the house of a high priest. Was this structure used by temple priests?

We concluded the excavation on August 11. Remarkably, this dig ended much the same way our 2018 dig ended: that is, with a bunch of exhausted, satisfied, grateful diggers; the base of a monumental Second Temple-period structure further exposed; a treasure trove of incredible finds; some questions answered; and more fascinating questions yet to be answered.

Like a great restaurant, we are already eager to return!