The Bible: The World’s Greatest Book on Astronomy

The late theologian and philanthropist Herbert W. Armstrong often said that man’s “first science experiment” took place in the Garden of Eden, when Adam and Eve decided to eat the forbidden fruit. “They decided to reject revelation imparted by God, and to make the very first scientific experiment!” he wrote.

What was their exact method? “They 1) rejected revelation, 2) used observation, 3) used experimentation, and 4) used human reason. And that is precisely the ‘scientific’ method used by modern science today!” (Why Were You Born? 1972).

This opening act in human history, he stated, formed the foundation of man’s often impressive, yet confusing and misguided, quest for knowledge. From the time of Adam, man has practiced a scientific method premised on a reliance on human reasoning and a rejection of revelation from God through the Bible.

This approach is particularly evident in man’s study of the universe. Many today would be surprised to learn just how much ancient astronomers understood about the universe. But for as much as they understood, it is remarkable how mistaken many of their conclusions were.

If only astronomers, both past and present, consulted the Bible. They would be stunned by what it reveals, both about the universe itself, and about man’s deeply flawed attempts to understand it.

Man’s Attempts at Studying the Universe

The earliest known telescope dates to 1608 c.e., making this piece of technology barely 400 years old. Without this remarkable invention, astronomers of the ancient world were unable to properly discern the difference between planets and stars. To them, planets traveling across the static night sky looked like moving stars. This is why, in ancient texts, planets were typically referred to as “wandering stars.” (In fact, our word “planet” is a holdover from this belief, from the Greek word for “wanderer.”)

The planets of our solar system are famously named after Roman and Greek deities (Venus, Jupiter and Saturn, for example, are all Roman gods). Most of these names were given in the first millennium b.c.e. The five planets closest to Earth are actually visible to the naked eye (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn); these are known as the “classical planets,” as they are documented in classical and ancient history.

Rather remarkably, links to all five of the classical planets—some more obvious than others—can be found in the Bible. These references are largely in a pagan context. For example, 2 Kings 23 records Josiah’s effort to purge Judah of idolatry. Verse 5 says, “And he put down the idolatrous priests … them also that offered unto Baal, to the sun, and to the moon, and to the constellations [other translations read, ‘to the planets’], and to all the host of heaven.” The Jews here had taken on the religious beliefs of their neighbors and were worshiping the planets, which they identified as gods.

In studying the various planets mentioned in the Bible, it is important to realize that the gods of Rome and Greece, including the ones representative of planets, are derivatives and iterations of the gods of ancient Mesopotamia. The Roman and Greek names for the planets are rooted in even earlier names, names that primarily originated in ancient Babylon and Sumer (biblical Shinar).

The Classical Planets

Take Venus, for example. This Roman goddess is modeled after the Greek Aphrodite, who herself is derived from the Babylonian goddess Ishtar. The name Ishtar means “star.” Depictions of this goddess, which date as far back as 2500 b.c.e., show her standing next to the symbol of the “star” Venus—the brightest object in the night sky (after the moon). In this manner, Ishtar also held the title “queen of heaven.”

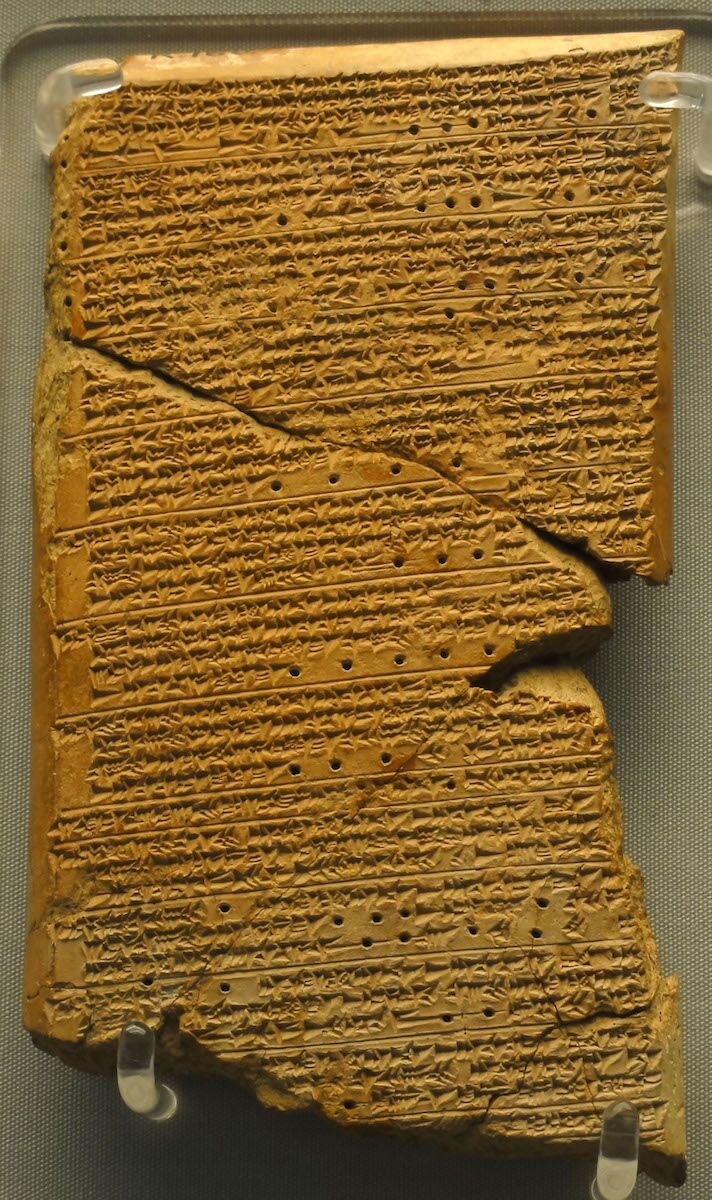

Some of the earliest known Babylonian astronomy texts describe observations of the planet Ishtar (later Venus), dating at least as far back as 1700 b.c.e. These texts include details such as the precise times of the rising and setting of this star. The Babylonian records about Ishtar are incredibly thorough and long-lasting. The fourth century b.c.e. Greek philosopher Callisthenes wrote of acquiring a series of Babylonian astronomy documents covering running observations of Venus, or Ishtar, throughout the prior 2,000 years.

Ishtar is referenced in multiple places in the Bible, generally by the Phoenician equivalent name “Ashtoreth” (likewise meaning “star”), and by her title “queen of heaven” (i.e. 1 Kings 11; Jeremiah 7 and 44; and Ezekiel 8; there is also an apparent mention of this planet by the name “Meni” in Isaiah 65:11, as related in Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon). “For Solomon went after Ashtoreth the goddess of the Zidonians [Phoenicians]” (1 Kings 11:5).

This kind of “planetary” worship even took place, during idolatrous periods, in the temple at Jerusalem. “And the king commanded … to bring forth out of the temple of the Lord all the vessels that were made for Baal, and for Asherah, and for all the host of heaven …”(2 Kings 23:4).

Saturn is another example. This planet is one of the most clearly attested to in the Bible. Amos 5:26 condemns the Israelites for having made idols to “Chiun … the star [planet] of your god ….” This passage documents the Israelites practicing planet-related worship. As Bible commentaries make clear, the name Chiun is well known as a reference to the planet Saturn. The Syrians, Arabs, Persians, Babylonians (and even the ancient Chinese) all referred to Saturn as some form of the name Chiun, or Kaiwan. The word means “steadfast,” which is fitting, since Saturn is the slowest-moving classical planet. (See here for more detail in relation to this biblical passage.)

The Prophet Amos was on the scene during the eighth century b.c.e. This alone would be notable for the early documentation of Saturn. But the context of the passage makes it even more interesting: Amos is describing the Israelites’ worship of Saturn during their 40-year sojourn in the wilderness, after they left Egypt in the 15th century b.c.e. “Was it to me you were bringing sacrifices and offerings during the forty years in the wilderness, Israel? No, you served your pagan gods—Sakkuth your king god and Kaiwan your star god—the images you made for yourselves” (verses 25-26; New Living Translation). Evidently, this planet had long been known to Israel.

What about Mercury, the small planet closest to the sun? In Isaiah 46:1, the Prophet Isaiah references the Babylonian gods “Bel” and “Nebo.” “Bel boweth down, Nebo stoopeth [or ‘sinks’]; Their idols are upon the beasts, and upon the cattle ….” Notice what Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon says about this verse: “Nebo [is a] proper noun [of] the planet Mercury, worshiped as the celestial scribe by the Chaldeans (Isaiah 46:1) and the ancient Arabians …. [Places like Mount Nebo] seem to have been so called from the worship of Mercury.”

Detailed Babylonian astronomy documents describe observations of Nebo in the night sky. Known as the “Mul-Apin tablets,” they date to around 700 b.c.e. (around the time of Isaiah’s writing). But experts believe them to be a compilation of earlier texts put together around 1000 b.c.e.—or perhaps even as far back as 1400 b.c.e. (In the Bible, the word Nebo is found as early as Numbers 32:3, during this circa 1400 b.c.e. time period.) These Babylonian texts refer to Nebo (Mercury) as the “running god.” (The Romans considered Mercury the “messenger” god.) Mercury has the fastest orbit around the sun (just 88 days).

Isn’t this remarkable? Astronomers more than 3,000 years ago recognized Mercury as the fastest-moving of the planets! Sure, they deified the planet as some sort of god or demigod. Still, this is a remarkable observation.

It is the same story with the other classical planets, Mars and Jupiter. Mars, known as the planetary deity Nergal, was an especially significant deity in the Assyrian city Nineveh (this is reflected in 2 Kings 17:30). Neo-Babylonian observations of the planet Nergal (Mars) are remarkably detailed and include the observation that this planet made 42 circuits of the zodiac every 79 years.

The Roman deity Jupiter is the later equivalent of Baal in the Bible. Jupiter was sometimes even referred to as Jupiter Belus, or “Jupiter Baal”. Other ancient gods that have been associated with the planet Jupiter include Marduk (Merodach; Jeremiah 50:2) and Gad (Fortune; Isaiah 65:11). The Babylonians also made some impressive calculations relating to this planet. For example, a fourth-century b.c.e. Babylonian tablet used a “trapezoid procedure” to calculate the orbit path of the planet. Mathematicians studying this ancient calculation recognize that it included one of the foundational principles of calculus, a field of math supposedly “discovered” 1,400 years later.

The level of understanding the Babylonians and other ancient peoples had of the stars and planets is simply extraordinary. These people used incredibly focused observation of the night sky, for incredibly long periods of time, to calculate planet trajectories and even foretell eclipses hundreds of years in advance! Impressive powers of observation and math were required to develop such understanding.

But what were the conclusions of this “experimentation” and “observation”? As the Bible itself attests, it was the widespread paganization of such physical objects: “gods, Which yet are no gods …. Be astonished, O ye heavens, at this …” (Jeremiah 2:11-12).

We’ve seen what the Bible says about what man says about the heavens. Now what does the Bible say about what God says about the heavens—the question of divine revelation? How does this early human experimentation and conclusion compare to what the Bible asserts to be revelation from God?

Revealed Knowledge

It might come as a surprise to learn that the Bible is quite a detailed astronomical text. Certain biblical figures, such as Job, David and Abraham, had a phenomenal understanding of the cosmos—an understanding ascribed to divine revelation. And in many respects, the Bible was thousands of years ahead of its time.

Let’s start with where we live: Earth. It wasn’t long ago that the prevailing general assumption was that the Earth was flat. The earliest-cited documentation of a spherical Earth dates to fifth century b.c.e. Greece. But notice what the Prophet Isaiah wrote several centuries earlier: “… Have ye not understood the foundations of the earth? It is He that sitteth above the circle [chug] of the earth …” (Isaiah 40:21-22). Gesenius’ Lexicon defines this Hebrew word chug as “a circle, sphere, used … of the world.” The Bible reveals the Earth to be round in shape—and Isaiah, chronologically, was on the scene during the eighth century b.c.e.

And this same word chug was used in another scripture chronologically attributed to nearly 1,000 years prior. Job—chronologically the earliest book in the Bible—states: “He has inscribed a circle [chug] on the face of the waters at the boundary between light and darkness” (26:10, English Standard Version). This circular boundary between daylight and night is, clearly, the result of the Earth being spherical in shape.

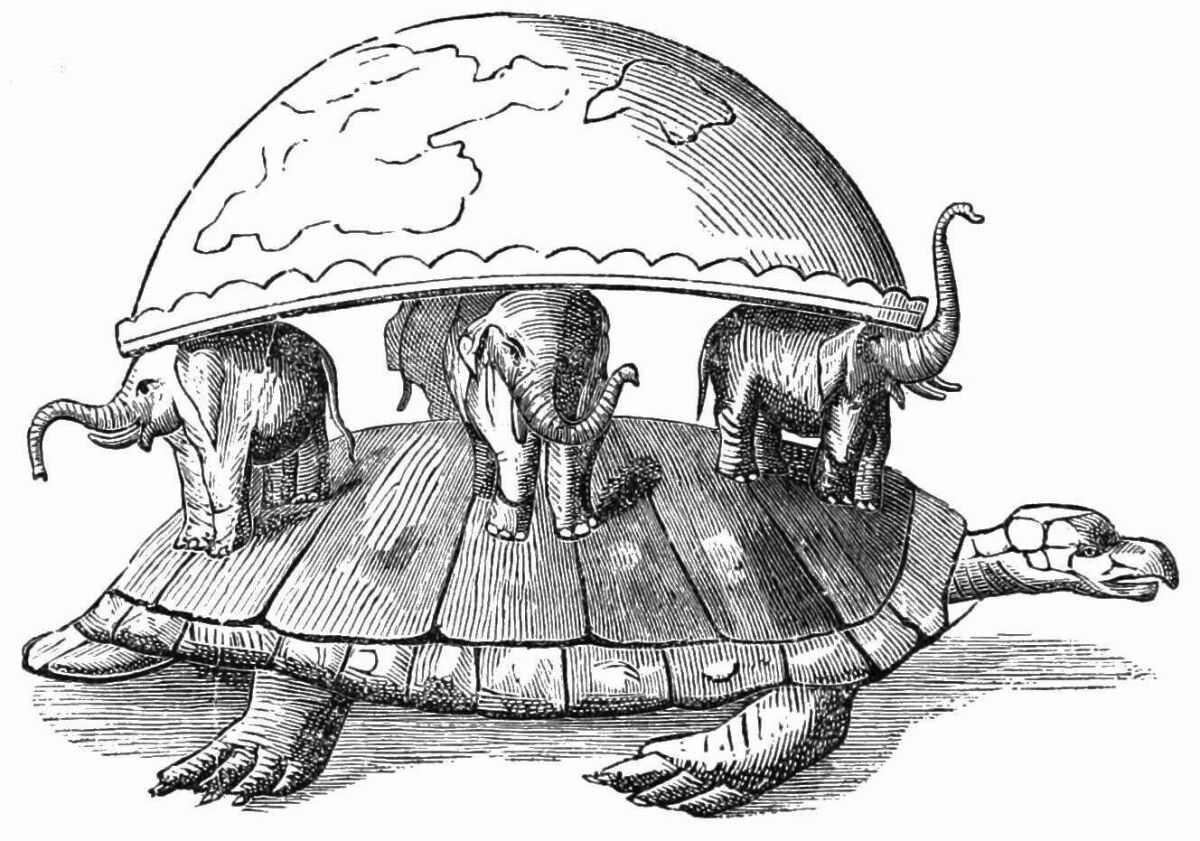

Today, we take it for granted that the Earth is “suspended” in space. But for thousands of years, different cultures believed the Earth was supported by giant pillars, animals or men. The sixth-century b.c.e. Greek intellectual Anaximander is recognized as one of the first to posit the idea that Earth was actually suspended in space. Later that century, Pythagoras conducted studies that he said proved Anaximander’s theory. Even still, the full scientific explanation of how the Earth “floats” in space wasn’t known until Isaac Newton discovered the theory of gravity in the late 17th century.

But even Pythagoras and Anaximander were 1,000 years too late. The book of Job records: “He [God] stretcheth out the north over empty space, And hangeth the earth over nothing” (Job 26:7)—clearly describing a suspended Earth!

Today, we understand the importance of the moon and its crucial role in sustaining weather patterns and tidal mechanics, and, by extension, life on Earth. Isaac Newton was, again, the first to explain the gravitational link between the tides and the moon. Before this, the Greeks in the fourth century b.c.e. were generally aware that the moon was connected to ocean tides.

Meanwhile, the book of Deuteronomy—written some one thousand years earlier—indicates that both the sun and moon play an active role on planet Earth. “[F]or the precious fruits brought forth by the sun, and for the precious things put forth by the moon” (Deuteronomy 33:14; King James Version). The words “put forth” can mean “a thing thrust forth.” This verse reveals an understanding that even the moon plays an active role in the Earth’s ecosystem. But what is mentioned specifically in the verse prior to this “thrusting forth” by the moon? The “watery depths”—the ocean (verse 13)!

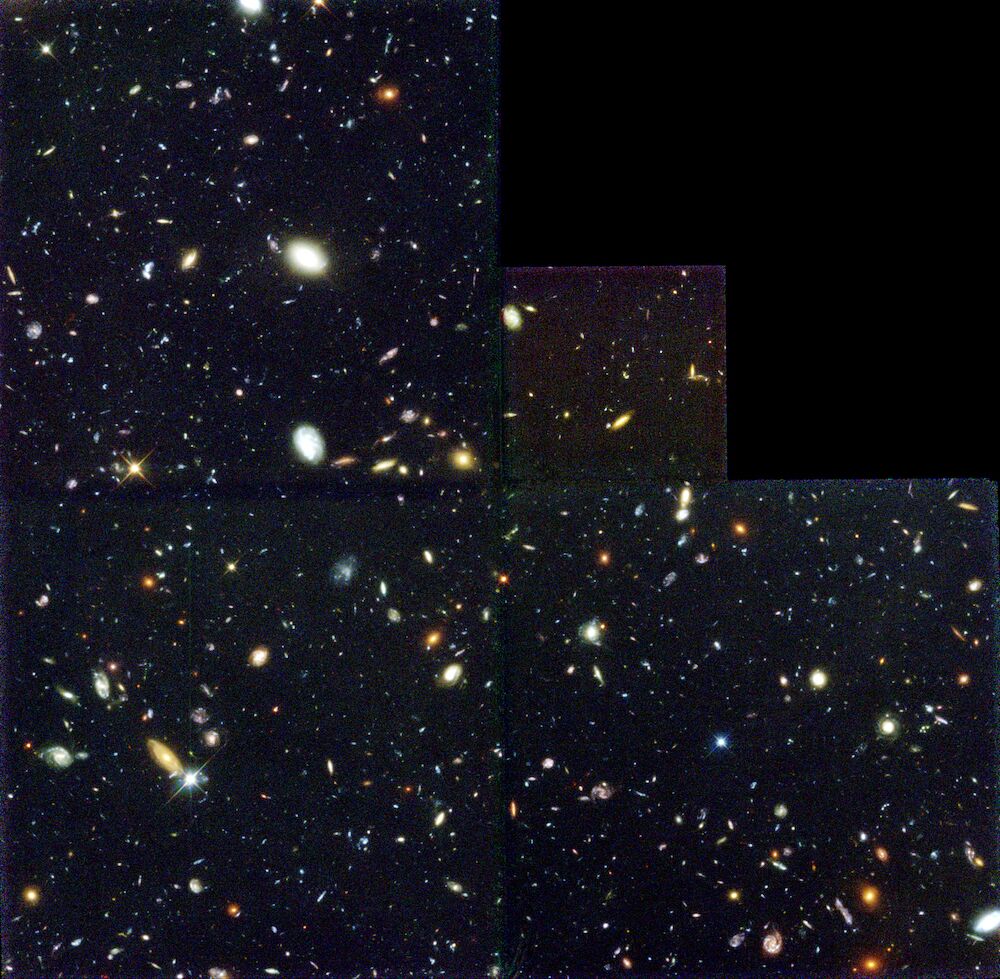

What about the stars? Before the invention of the telescope, esteemed scholars of the ancient world, such as Ptolemy (150 c.e.), believed that there were fewer than 3,000 stars. We now know that the Milky Way galaxy alone contains 400 billion stars, and that the observable universe contains more than 170 billion galaxies, many of which contain trillions of stars each. The number of stars in the universe beyond that is unknown.

Again, the Bible was thousands of years ahead of its time. Writing in the sixth century b.c.e., the Prophet Jeremiah stated, “[T]he host of heaven cannot be numbered …“ (Jeremiah 33:22).

The Bible also contains several references to different identifiable constellations. And there are some real gems contained in these scriptures. One of the most famous is the “mighty hunter” Orion and his “belt” of three stars. The Orion constellation (Hebrew, Kesil) is mentioned in several Bible verses (e.g. Amos 5:8).

In Job 38:31, God actually challenges Job to see if he can “loose the bands [or belt] of Orion.” In this passage, God implies that the belt of Orion is being loosed—challenging Job, could a mere human like himself loose this belt? In recent years, scientists have discovered that the belt of Orion is in fact very slowly “loosing.” Astronomer Garrett Serviss writes: “The great figure of Orion appears to be more lasting, not because its stars are physically connected, but because of their great distance, which renders their movements too deliberate to be exactly ascertained. … [T]here is a little movement perceptible in the ‘Belt.’ … In the course of time … the third [star], Alnita, will drift away eastward, so that the ‘Belt’ will no longer exist” (Curiosities of the Sky).

Another constellation mentioned in the Bible is the Pleiades (Hebrew Kimah). In the same verse, God challenges Job to keep this constellation together: “Canst thou bind the chains [or cluster] of the Pleiades …?” Here again, astronomers have only recently discovered that these “seven sisters,” as they are sometimes called, are indeed bound to one another by “mutual gravitational attraction.” nasa scientists have discovered that the whole constellation is very gradually moving—but moving together. Could a mere human like Job keep this constellation bound?

In the next verse, God challenges Job to “guide Arcturus with his sons” (kjv). In the ancient world, Arcturus was known only as a single star. But in 1971, scientists discovered 52 other stars—“sons,” in a sense—that make up the “Arcturus Stream.” One astronomer describes Arcturus and his stream as “runaway” and a “law unto themselves,” due to their fast-moving speed. Could a mere human like Job guide the Arcturus Stream? (These details, and more, are highlighted in J. Warner Wallace’s article “Is the Astronomy in the Book of Job Scientifically Consistent?”)

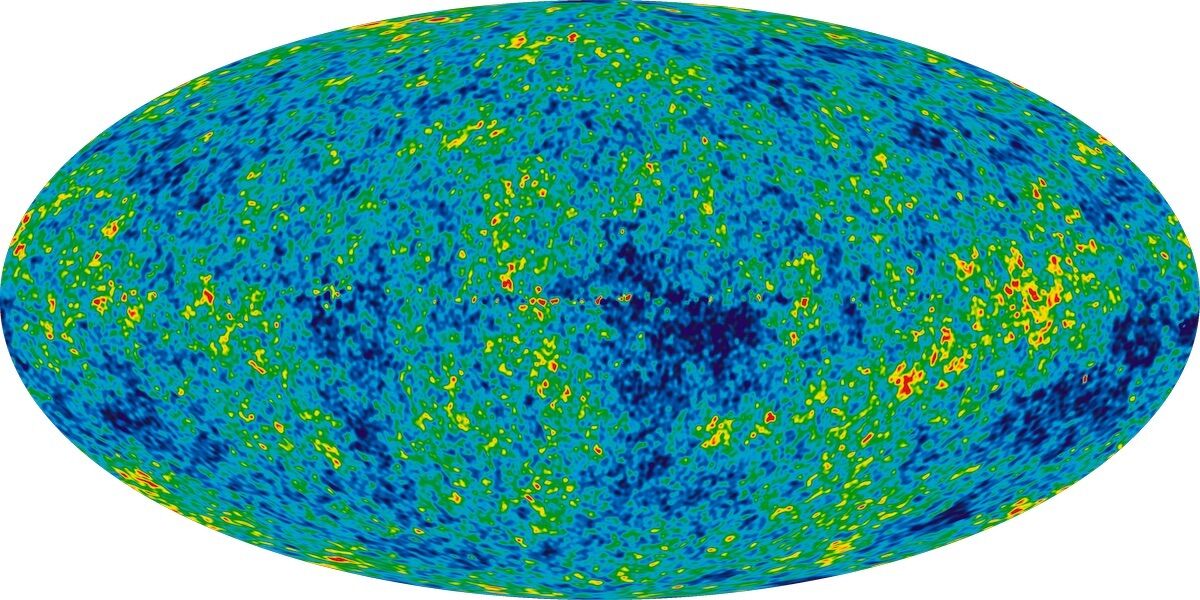

In the fourth century b.c.e., the famous philosopher Aristotle stated that the universe was finite in size and had remained unchanged throughout eternity. This theory prevailed until 1576, when English astronomer Thomas Digges posited the idea that the stars extend infinitely. This theory was solidified in the 17th century by René Descartes and Isaac Newton. In 1929, by measuring the redshifts of a number of distant galaxies, Edwin Hubble proved that the universe is actually expanding.

Without the benefit of modern technology, the Bible revealed this same reality—3,500 years earlier. Job 9:8 says that “[God] alone stretcheth out the heavens.” The Prophet Isaiah stated that God “stretcheth out the heavens as a curtain” (Isaiah 40:22; 45:12; see also, Zechariah 12:1).

Two Trees—Two Universes

As Herbert Armstrong explained, there are two entirely different methods of knowledge acquisition. One is gaining knowledge by relying entirely on human observation, experimentation and reason. This is the path mankind at large walks. While this mode of education can lead to some remarkable discoveries (as well as some apocalyptic inventions), it will inevitably draw irrational conclusions: for example, the treatment by the ancient pagans of virtually everything as a god, including the entirely predictable planets; or conversely, in modern science, attributing nothing to a higher power—the belief that the entire universe simply “exploded” into existence from nothing.

Then there is the second method of acquiring knowledge. Under this method, material knowledge is filtered through, and interpreted by, revelation from God, with the Bible as the foundation of all knowledge. This is the method employed by the great biblical writers. Was Jeremiah an astronomer? Isaiah? Moses and Job were not professional cosmologists. Yet their writings were, in several respects, thousands of years ahead of the great scientists of more recent history.

How is this possible? How did the authors of the Bible have insights into the universe that others lacked? “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge,” the wisest man on Earth once wrote (Proverbs 1:7).

As the Bible relates right from the beginning, Adam took for himself the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. It was a tree of knowledge—but a knowledge of dangerously mixed value, one leading to wrong conclusions entirely, based on a rejection of God.

As for the other tree? It is the tree of life—but it too is a tree of knowledge, based on divine revelation. “For the Lord is a God of knowledge …” (1 Samuel 2:3). “[K]nowledge [that] is too wonderful for me; Too high, I cannot attain unto it” by mere human means (Psalm 139:6).

Two trees—two choices. But only one truly unlocks the secrets of the universe.