Is It Really King David’s Palace?

“Did I find King David’s palace?” Archaeologist Eilat Mazar asked that bold question in the January/February 2006 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review. Her lengthy article summarized her 2005 archaeological excavation at the northern tip of the City of David and the scientific evidence she had uncovered.

Since it was published, Dr. Mazar’s article, and her work in the City of David, has drawn a spectrum of responses, from the scholarly and scientific communities as well as the public. Some are convinced, some are uncertain and some are dismissive of, and some even hostile to Dr. Mazar’s discovery and identification.

In June, Ruth Margalit wrote a lengthy New Yorker article on the historicity of King David. In a couple of short paragraphs, Margalit briefly and dismissively mentioned the structure Dr. Mazar excavated but presented no real evidence for or against its identification as David’s palace. Later in the piece, she flatly claimed that there has been a “failure to locate the ruins of David’s palace.” (Margalit didn’t simply ignore crucial hard evidence, her op-ed relied heavily on the theories of the famously “anti-David” Israeli archaeologist, Prof. Israel Finkelstein.)

Similar feature stories on King David and his palace have been published in other prominent outlets, from the National Geographic to Israel’s Haaretz to Germany’s Der Spiegel. These articles generally take the same view of David’s palace, and nearly always follow the same logic. They downplay and even ignore the scientific evidence and historical record; meanwhile, they emphasize the dissension.

In this article we present the archaeological evidence that led to Dr. Mazar’s conclusion that she had discovered King David’s palace. And you can make up your own mind—based on the evidence.

Pinpointing the Location

Almost 10 years before she began digging in the City of David, Dr. Mazar wrote an article explaining why she believed King David’s palace was located in the northern end of the City of David. The article was titled “Excavate King David’s Palace!” and appeared in the January/February 1997 Biblical Archaeology Review.

“[A] careful examination of the biblical text combined with sometimes unnoticed results of modern archaeological excavations in Jerusalem enable us, I believe, to locate the site of King David’s palace,” she wrote. “Even more exciting, it is in an area that is now available for excavation. If some regard as too speculative the hypothesis I shall put forth in this article, my reply is simply this: Let us put it to the test in the way archaeologists always try to test their theories—by excavation.”

Mazar’s hypothesis relied on clues found in the Bible —specifically 2 Samuel 5. This chapter describes David’s capture of Jerusalem (verses 6-9), and the construction of his new palace (verse 11). But it was a verse further along in the chapter that caught Dr. Mazar’s eye: “And when the Philistines heard that David was anointed king over Israel, all the Philistines went up to seek David; and David heard of it, and went down to the hold” (verse 17).

This verse contains several notable details, which Dr. Mazar was willing to believe. First: the word “hold” refers to the original walled fortress of Jebus (Hebrew: metsudah). It is named as the metsudah of Zion during David’s attack described in verse 7. Verse 9 records that after David conquered the metsudah, he immediately moved into it. Verse 11 records that not long afterward, the Phoenician king Hiram sent skilled laborers to help “build David an house.”

King David clearly had a palace: The question is, where exactly was it situated?

The fortress-city of Jebus covered only about 48 dunams (12 acres), primarily made up of the southern sloping ridge of Mount Zion. Archaeologists have revealed a general idea of the extent of Jebus, and estimate that around 500 people lived within its walls. Given that this was such a compact and populated area, would there have been sufficient room inside the city for a grand palace? Or did David build his new palace just outside the original walls?

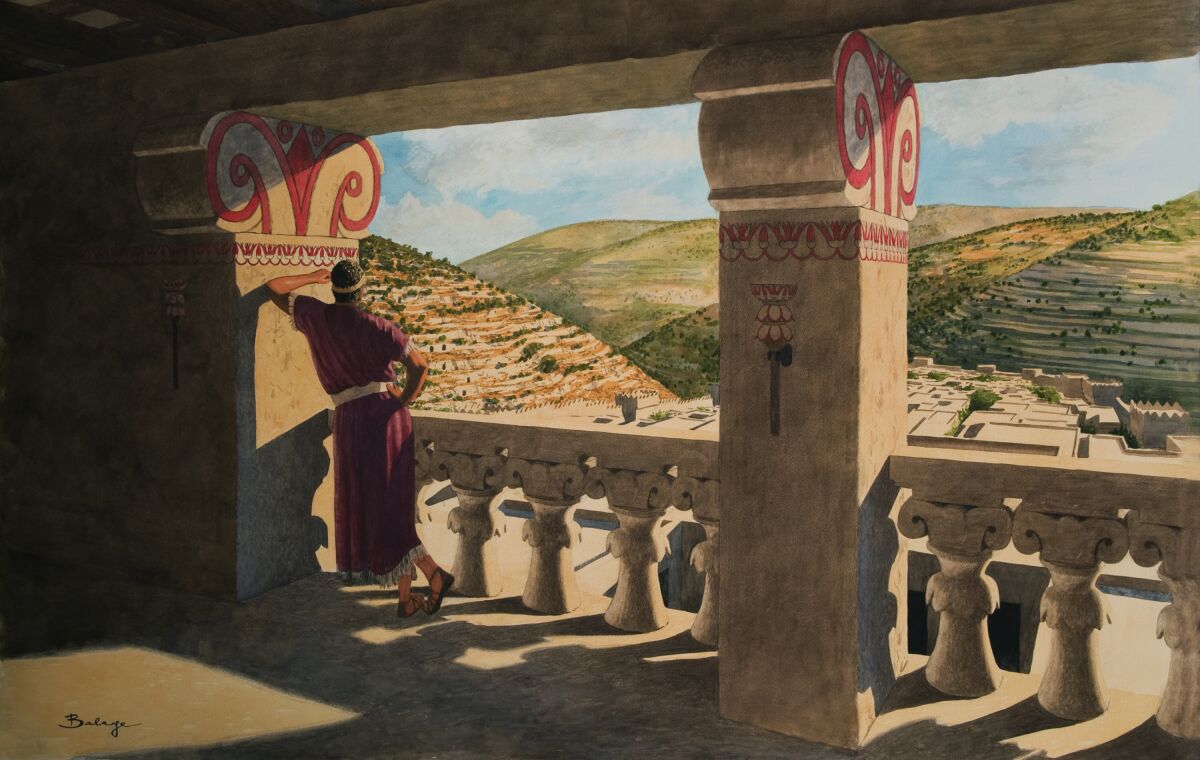

Verse 17 shows that after David settled into his new palace, he heard reports of an imminent Philistine attack and went down into the metsudah, or fortress/hold. David’s palace, then, had to be located in an elevated location, above the fortress, and just outside the city walls. (Later, David’s palace would be surrounded by a fortified city wall. The Bible records that David’s son Solomon and other kings built additional walls around Jerusalem as the city expanded further north.)

Dr. Mazar believed, then, that David’s palace would be found just outside the north wall of Jebus, in an elevated position on Mount Zion.

When she discussed this theory with her grandfather, former Hebrew University President Prof. Benjamin Mazar, just before his death in 1995, he reminded her of an impressive royal Phoenician pillar capital that had been discovered by archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon during excavations in the City of David in 1962.

Kenyon’s reports stated that the capital, of a type belonging to the early Israelite monarchy, was found part way down the eastern side of the hill, directly below the location where Mazar believed David’s palace would be found. Evidently, the capital had fallen from a palatial structure further up the hill. Did this pillar capital belong to David’s palace?

Dr. Mazar compiled her research and presented her theory in a 1997 Biblical Archaeology Review article. But the theory was met with little enthusiasm from the academic world. Some archaeologists questioned the merits of excavating where Mazar suggested, expressing doubts that she would uncover evidence of anything, let alone a palace. Earlier excavations in the City of David, they said, had left little remaining to be discovered.

Dr. Mazar wasn’t deterred. While previous excavations in the City of David had uncovered plenty of later period walls, Mazar believed that Iron iia remains could still be discovered below these structures. More than anything, Mazar, like any good scientist, wanted to put her theory to the test: She wanted to dig!

But she lacked financial support to fund the proposed excavation. It wasn’t until nearly a decade later, in 2005, that she received funding from Roger and Susan Hertog and Eugene and Zara Shvidler.

Now she could dig.

The Stepped Stone Structure

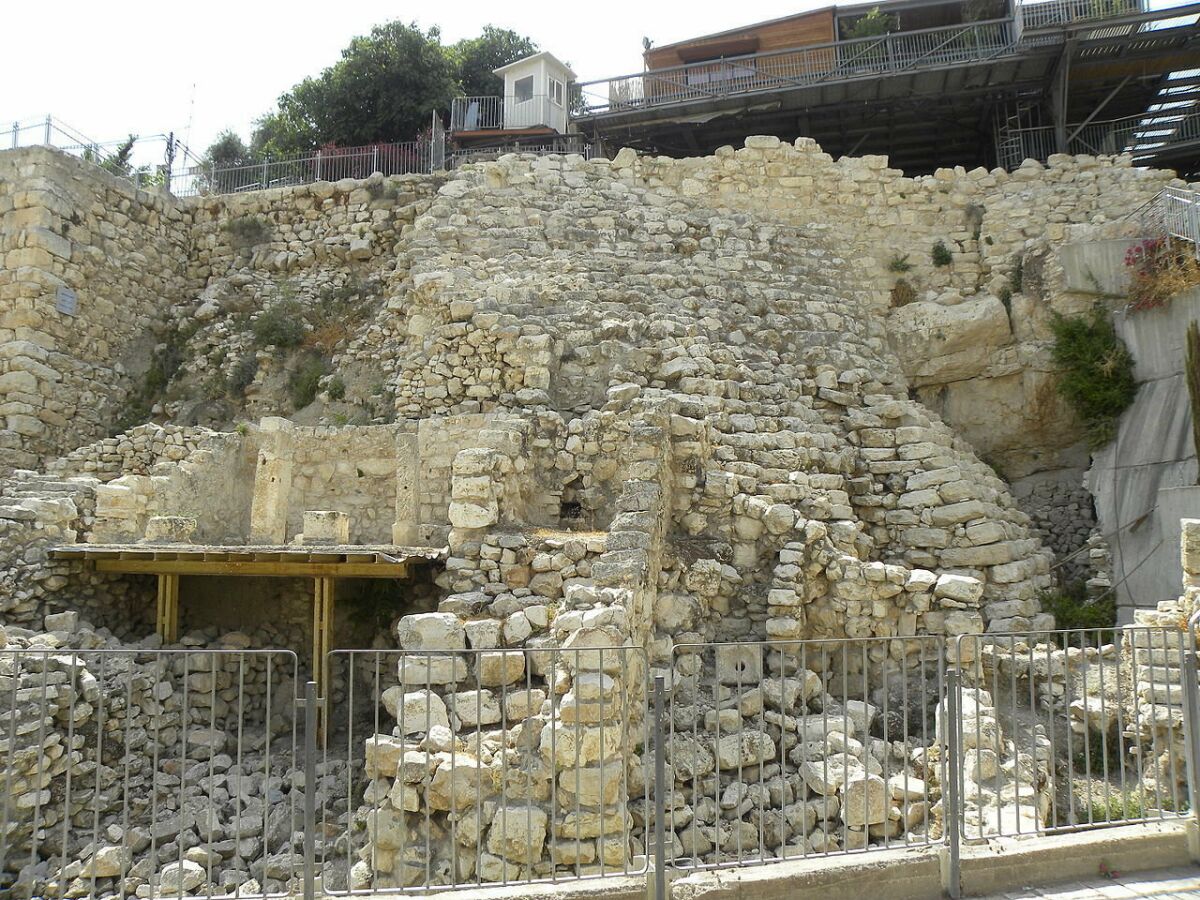

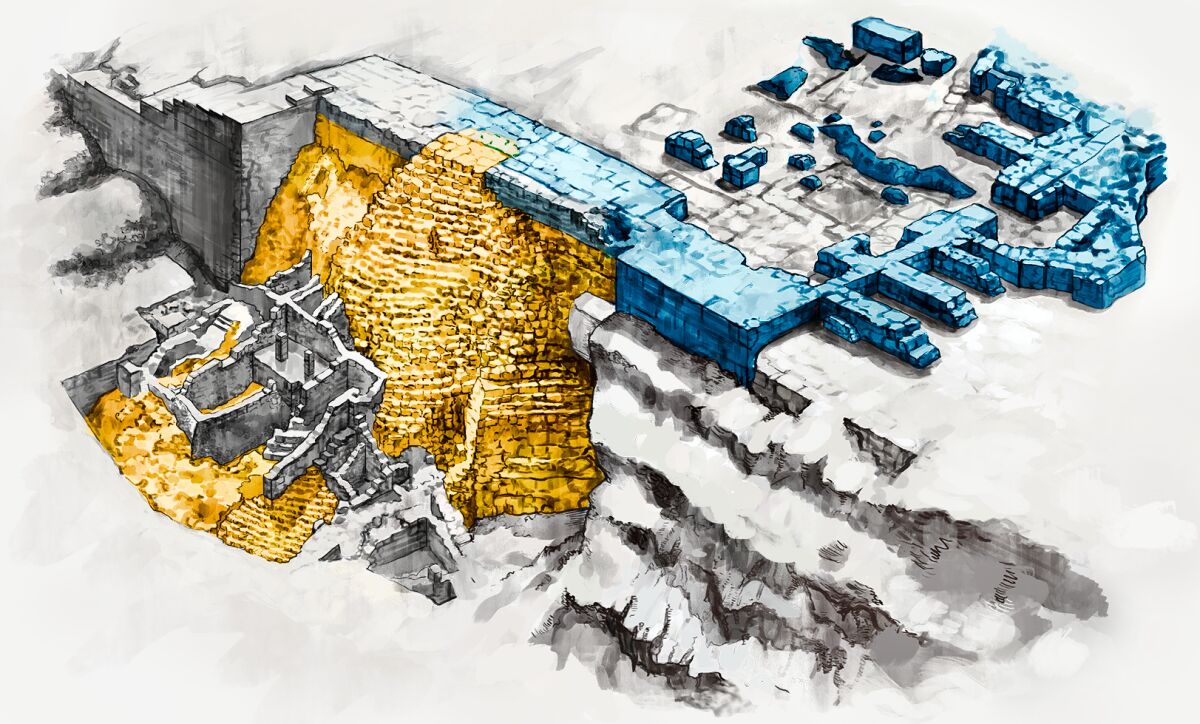

When Dr. Mazar published her Biblical Archaeology Review article in 1997, she was most interested in excavating the area north of the famous Stepped Stone Structure in the City of David. But by the time Dr. Mazar received funding for the excavation, the only area that was then approved for excavation was a little further south: an area just above and slightly to the north of the Stepped Stone Structure.

The Stepped Stone Structure in the City of David is one of the largest and most impressive archaeological features in Israel. Situated on the east side of Mount Zion, this monumental edifice is 20 meters high. It has been excavated around half a dozen times throughout the past century. Since the 1970s, the common belief was that the Stepped Stone Structure was constructed earlier than King David’s time, with some additions occurring into the ninth century b.c.e.

Dr. Mazar had assumed, as had some of her colleagues, that the area just above the Stepped Stone Structure belonged to the northern part of the Jebusite fortress that David “went down to” from his palace. She thought that the palace would be found further north—frustratingly, just outside of the area she was approved to dig.

“Eventually they gave me the option to excavate in a place where I thought the [Jebusite] fortress of Zion was going to be revealed,” she told AIBA in late 2019. “I thought I was going to miss King David’s palace. But I excavated where they let me excavate. It’s not like I could choose. I took what I got.”

The Large Stone Structure

Dr. Mazar began her excavation in mid-February 2005. Within two weeks, her team had unearthed massive walls. They were staggered by the sheer size of the walls. One wall, running east-west, was 30 meters long and up to 3 meters wide. Another even larger wall was uncovered during the next season of excavations (summer 2006). This wall ran north-south and was 6 meters wide.

That’s not all. This massive north-south wall directly abutted the top of the Stepped Stone Structure. A small excavation in the summer of 2007 revealed that this wall not only touched the Stepped Stone Structure but actually interlocked with it.

The way this massive north-south wall connected to the Stepped Stone Structure indicated that both edifices were part of the same building.

This was a crucial discovery. “The fact that the two structures were part of the same construction was an astonishing discovery for us,” Dr. Mazar said. “Laid before our very eyes was a structure massive in proportions and innovative in complexity. It bears witness to the impressive architectural skill and considerable investment of its builders, to the competency of a determined central ruling authority, and most notably to the audacity and vision of that authority.”

In addition, Dr. Mazar discovered the reason the Stepped Stone Structure was constructed in the first place. The bedrock at the top of Mount Zion contained a large void. If the ruler of the fortress wished to extend his city further to the north along the ridge of Mount Zion, this gap would have to be bridged by a massive foundation fill so a sturdy structure could be built atop it—a Stepped Stone Structure. This would require, to use Dr. Mazar’s words, the “audacity and vision” of a “determined central ruling authority” to devote enormous resources to build such a brace, descending down into the Kidron Valley.

This, then, is what we see with the foundational Stepped Stone Structure and building above: the construction of a gigantic palatial structure with walls up to 6 meters wide, woven into a 20-meter-high Stepped Stone Structure that provides a firm foundation down the steep eastern edge of the City of David. This joint building effort constitutes the tallest known structure in all Israel until the time of Herod the Great, nearly 1,000 years later. The height and mass of the Stepped Stone Structure testifies to the outstanding size and magnificence of the building it supported.

Dr. Mazar called the newly discovered massive building, built directly atop and interlocking with the Stepped Stone Structure, the “Large Stone Structure.” This structure could only be built through a significant degree of wealth, infrastructure and power. This raised a crucial question: Who built it? Could it have been the palace of King David?

Was This Really the Palace?

To determine if the Large Stone Structure was David’s palace, Dr. Mazar needed more than a large building underpinned by a gigantic supporting structure. She needed to date the building. The standard way to do this is to use material remains, especially pottery and carbon samples, that relate to the structure.

During her 2005–2008 excavations, Dr. Mazar’s team uncovered a significant amount of pottery and many carbon samples related to the Large Stone Structure. When studied in the laboratory, Mazar discovered that the material found directly under the Large Stone Structure dated to the last part of the Iron i period—around the 11th century b.c.e. This was the last period in which the Jebusite Canaanites occupied Jerusalem, just before David conquered the city.

These fragments—alongside lack of any structural remains dating to this period, indicated that the Jebusites had left this area open and unbuilt, just outside the northern extent of their city.

The artifacts discovered abutting and directly associated with the Large Stone Structure—and thus the Stepped Stone Structure—were scientifically dated to around the first part of Iron iia: circa 1000 b.c.e.

The combined dating evidence left a window of less than 100 years in which this massive building could have been constructed. And directly within that time period is the biblical account of the reign of King David!

Based on her discoveries, Dr. Mazar found that the evidence fit precisely with the biblical account of David’s palace: She had found a massive, 3,000-year-old building right where the Bible says David’s palace should be!

Additional Evidence

Outside of the right location and right dating, a number of smaller discoveries also identify the Large Stone Structure as King David’s palace. The Bible records that the Phoenician King Hiram sent stone masons to work on David’s palace (2 Samuel 5:11). This fits with the discovery of the beautifully worked Israelite-Phoenician style stone capital that Kenyon found below the now-uncovered Large Stone Structure; this too dated to the Iron iia period.

Other royal items were discovered in and around the palace, including ornate ivory utensils and the remains of exotic foods, likewise indicating the royal nature of the structure.

The Bible records that after King David died, his son Solomon built another palace further north of the City of David (1 Kings 7:1). Future kings ruled from this northern palace, which became known as the “king’s high house” (Nehemiah 3:25; King James Version). But the palace David built continued to function as a royal building, and was still identified as the “house of David” in the days of Nehemiah (Nehemiah 12:37).

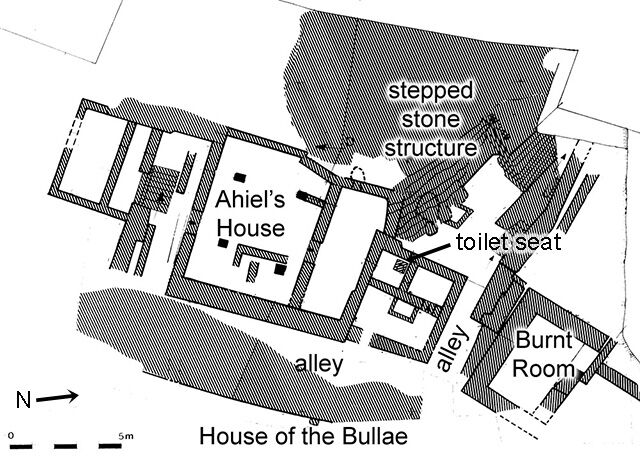

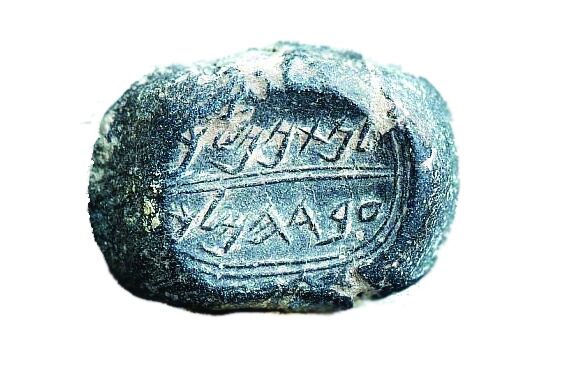

Jeremiah 36:12 describes an officer going “down” into a scribal chamber near the “king’s house,” and meeting with several officials, including Gemariah the son of Shaphan. Excavations of the Stepped Stone Structure in the 1970s by Prof. Yigal Shiloh revealed a scribal chamber at the base of the structure containing 51 bullae. The building became known as the “House of Bullae.” One of the bullae discovered contained an inscription reading “Belonging to Gemariah, son of Shaphan.” The House of Bullae, then, is a close link to the “scribe’s chamber” near the “king’s house.”

Within and around the Large Stone Structure, the bullae of two princes were discovered by Dr. Mazar in 2005 and 2007. The first reads: “Belonging to Jehucal, son of Shelemiah, son of Shovi.” The second reads: “Belonging to Gedeliah, son of Pashur.” These royal princes are described together in Jeremiah 38:1 as the enemies of the prophet. It would be fitting to find evidence of princes around a royal palace structure.

In excavations to the west of the Large Stone Structure, two other notable bullae were found in the 2019 excavations of Prof. Yuval Gadot: One, “Belonging to Nathan-Melech, Servant of the King” belonged to one of King Josiah’s royal chamberlains (2 Kings 23:11). The other, “Belonging to Ikar, son of Mattaniah,” may have belonged to a prince and son of King Zedekiah (whose original name was Mattaniah).

Dozens of other bullae from royal officials and princes scattered in and around the Large Stone Structure and the nearby scribal building go together to indicate that the Large Stone Structure was a royal edifice, a palace.

A Sensational Discovery

When Dr. Mazar released her discovery to the public in 2005, it generated attention around the world. It was on the front page of the New York Times. However, a number of scholars decried it as sensationalism.

Why was this viewed so negatively? This was a sensational discovery! Dr. Mazar had uncovered evidence of a massive building, one that was dated to the very time and location of King David, one of the Bible’s greatest figures.

Why did Dr. Mazar receive so much criticism? Did she skew the evidence? Was she being intellectually dishonest? What motivates the criticism against Dr. Mazar’s identification of David’s palace? Is Mazar biased—or is it her critics who are biased?

Dr. Mazar’s sensational finding was greeted with some skepticism because she committed two cardinal sins: First, she discovered what she was looking for. Second, Mazar’s science was informed and influenced by the Bible.

Addressing the first point: Remember that Dr. Mazar initially believed David’s palace to be slightly further north than where she was approved to excavate. Like other archaeologists, Mazar also believed the area directly above the Stepped Stone Structure was likely part of the Jebusite fortress that was built well before David was born. Not until the discovery was dated did Dr. Mazar change her mind and conclude that the Large Stone Structure was built too late to be the Jebusite fortress—it had to have been constructed during King David’s reign.

“Even when I proposed looking for the remains of King David’s palace at this spot, I did not imagine that the Stepped Stone Structure would form an integral part of it,” Dr. Mazar wrote in 2009. “Indeed, reality surpassed all imagination.”

Integral to science is the development and testing of a theory. Finding what you are looking for is not simply a sign of bias. It’s a sign of a good theory.

As for the second point, it is important to also note that while Dr. Mazar does consider the Hebrew Bible a valuable resource for studying history, she is not religious and does not pursue a religious agenda. “Archaeology cannot stand by itself as a very technical method,” she said. “It is actually quite primitive without the support of written documents. Excavating the ancient land of Israel and not reading and getting to know the biblical source is stupidity. I don’t see how it can work. It’s like excavating a classical site and ignoring Greek and Latin sources. It is impossible.”

Dr. Mazar digs up stones and walls and pottery. If she finds them to match the biblical record, then she does not shy away from making the obvious associations (as some archaeologists admittedly do—out of fear of their work being branded “sensationalist” and discredited by their fellow academics).

To Dr. Mazar, the Bible records ancient history in Jerusalem relating to ancient structures in Jerusalem. “I am interested in history, not just about stones. I am interested in stones that can speak. I don’t care about stones that have nothing to talk about. That are speechless. Who cares about speechless stones?”

“Let the stones speak,” she so often says.

Following her initial excavation in 2005–2006, some of Dr. Mazar’s colleagues rejected the conclusion that she had discovered King David’s palace. Some said the Large Stone Structure was from 700 years later. Some said it was totally unrelated to the Stepped Stone Structure. Others held fast to the original theory and maintained that it was a Jebusite fortress. One professor recently dismissed Dr. Mazar’s discovery, claiming she hadn’t done carbon dating. Odd, because she most definitely had—we should know, we helped in her excavations. But this is an example of the careless dismissal of Dr. Mazar’s evidence—without evidence of their own!

These conclusions are the hasty speculations and assumptions based on limited evidence, in some cases made by individuals who have never led excavations in Jerusalem. Dr. Mazar’s conclusion came from years of theorizing and leading actual excavations producing a growing body of supporting evidence.

It is true that 3,000 years of habitation and development make it impossible to distinguish the precise design and layout of David’s palace. However, the main outer walls dated to the time of King David are easily visible at the site.

In recent years, as more evidence of David’s kingdom has emerged, biblical minimalists have started to acknowledge that although the walls are not inscribed with King David’s personal signature, they are inarguably the foundations of a massive building within the (albeit contested) timeframe supported by pottery reading, carbon dating, many traditional archaeologists and the Bible.

Some archaeologists have suggested that the Large Stone Structure is a massive Jebusite building that was constructed at the end of Jebusite rule over Jerusalem. In her preliminary report published in 2009, Dr. Mazar recognized that this is possible. But she also explained why it is highly unlikely. While the dating of the structure could support that conjecture, logic does not. Why would the Jebusites invest time and resources building a massive palatial structure outside their fortress city—and at a time when the Israelites were growing in power and preparing to conquer the Jebusite city nestled in the heartland of their territory? This and other theoretical attempts to explain away the structure are much more of a stretch, and take far more imagination, than pairing it up with the straightforward biblical account.

If you have an open mind and follow the evidence, furnished by both archaeology and the historical record (the Bible), the most logical explanation is that the Large Stone Structure and the Stepped Stone Structure form one massive edifice—the palace of David, king of Israel.

“There may be times when it will take 10 years for people to adjust to, support and even accept the idea,” Dr. Mazar said, “but I am not going to wait for them.” She estimates that only 20 percent of the royal building has been uncovered. And she wants to keep digging.

Dr. Mazar concluded her 1997 Biblical Archaeology Review article by writing: “The biblical narrative, I submit, better explains the archaeology we have uncovered than any other hypothesis that has been put forward. Indeed, the archaeological remains square perfectly with the biblical description that tells us David went down from there to the citadel. So you decide whether or not we have found King David’s palace.”

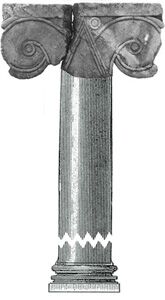

Sidebar: Kenyon’s Proto-Aeolic Capital

By Eleanor Clarke

The discovery of proto-Aeolic capitals testifies to the royal grandeur of ancient Israel. A capital is the highly decorative uppermost stabilizing part of a column. The more ornate the pillar capital, the more prestigious the building it belonged to. The “proto-Aeolic” moniker refers to a particular early Phoenician-Israelite-style design, depicting two palm motifs (classic symbolism found in Israel and Phoenicia).

The finest example of these capitals was found in Jerusalem in 1963, during excavations at the base of the Stepped Stone Structure. Archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon discovered a massive proto-Aeolic capital broken in half, found among debris and ashlars that had evidently fallen from a royal structure further up the hill. Prof. Yigal Shiloh, who conducted an extensive study of proto-Aeolic capitals, said it was “especially superior.” Shiloh also called it “the finest of all the proto-Aeolic capitals in this country.” Prof. Oded Lipschits said that such capitals provide an indication of the scale and opulence of gates and palaces that they were part of.

During excavations of the City of David, Kenyon found a small section of a massive structure dating to the 10th century b.c.e. At the time, Kenyon considered this to be a part of a casemate wall built by King Solomon. Some 30 years later, Dr. Eilat Mazar theorized that it could instead be the location of King David’s palace.

When Dr. Mazar shared her thoughts with her grandfather, Prof. Benjamin Mazar, he was enthusiastic. “Where exactly did Kenyon find the piles of ashlars together with the proto-Aeolic capital?” he asked. “Wasn’t it right next to the place you’re talking about?”

Indeed it was. The proto-Aeolic capital was found at the foot of the southeastern edge of the structure. The capital, together with the beautiful ashlar stones, had clearly fallen from an impressive building. Dr. Mazar wrote: “This was just the kind of impressive remains that one would expect to come from a 10th-century b.c.e. king’s palace.”

2 Samuel 5 records the construction of David’s palace. Soon after David became king of Israel, Hiram, the Phoenician king of Tyre, sent craftsmen and materials to help build the palace: “Then King Hiram of Tyre sent messengers to David, along with cedar timber and carpenters and stonemasons, and they built David a palace” (verse 11; New Living Translation).

The Oxford History of the Biblical World describes the proto-Aeolic capital this way: “The high quality and uniformity of these features of the monumental architecture of the 10th century represent a building style that may have been designed in the United Monarchy by an unknown royal architect.”

The royal architect may be unknown. But it is certainly fitting for the most grandiose Israelite-Phoenician capital to have been found at the base of a 10th-century palatial building in the City of David, matching the biblical account of a palace built with the help of a Phoenician king for the ruler of Israel’s united monarchy.