Does the Mesha Stele Say Omri Reigned 40 Years?

There has been a lot of debate over whether the number 40 in the Bible, which appears with some frequency, should be taken literally or figuratively as some kind of sign for an indeterminate sum.

The wilderness sojourn, for example, is described as lasting 40 years (e.g. Numbers 32:13), thus often regarded as an indeterminate round figure. Yet this block of time is elsewhere outlined in further detail, such as the Israelites’ departure from Sinai “in the second year” of the Exodus (Numbers 10:11), followed by “thirty and eight years” of wandering from Kadesh-barnea to Zered (Deuteronomy 2:14). Similarly, the reign of David is given as 40 years (e.g. 2 Samuel 5:4)—yet again is elsewhere subdivided into “seven years and six months” in Hebron and “thirty and three years over all Israel” (verse 5). Moses’s age is given as 80 at the time of his interactions with Pharaoh (Exodus 7:7)—a multiple of 40. Yet in the same verse the very specific corresponding age of 83 is given for his brother Aaron. Still, there are several examples of the number 40 (and multiples thereof) found in the Bible without such specific breakdowns or additional context.

This debate over whether to take the number 40 literally, close to literally (i.e. as a rounded approximation of a similar sum), or as something entirely separate and symbolic, has played a key role in the dialogue about when the Exodus took place. 1 Kings 6:1 states that King Solomon began to build the temple in his fourth year—fairly widely agreed upon as circa 967 b.c.e. (debate on this generally ranges within a few years and is, therefore, negligible)—and that this was “in the four hundred and eightieth year after the children of Israel were come out of the land of Egypt.” Taking this figure literally would place the Exodus generally within the mid-15th century b.c.e.—more specifically, counting back from circa 967 b.c.e., around 1446 b.c.e.

This is nearly two centuries prior to the comparatively popular 13th-century b.c.e., Ramesside Exodus theories. As such, those holding to this late-date position typically argue that the 480 figure is “symbolic,” a non-literal multiple of 40, and thus should not be used for placing the Exodus. Early-date proponents typically respond by highlighting other scriptures (such as Judges 11:26 and 1 Chronicles 6) that point to the same ballpark, 15th-century b.c.e. date.

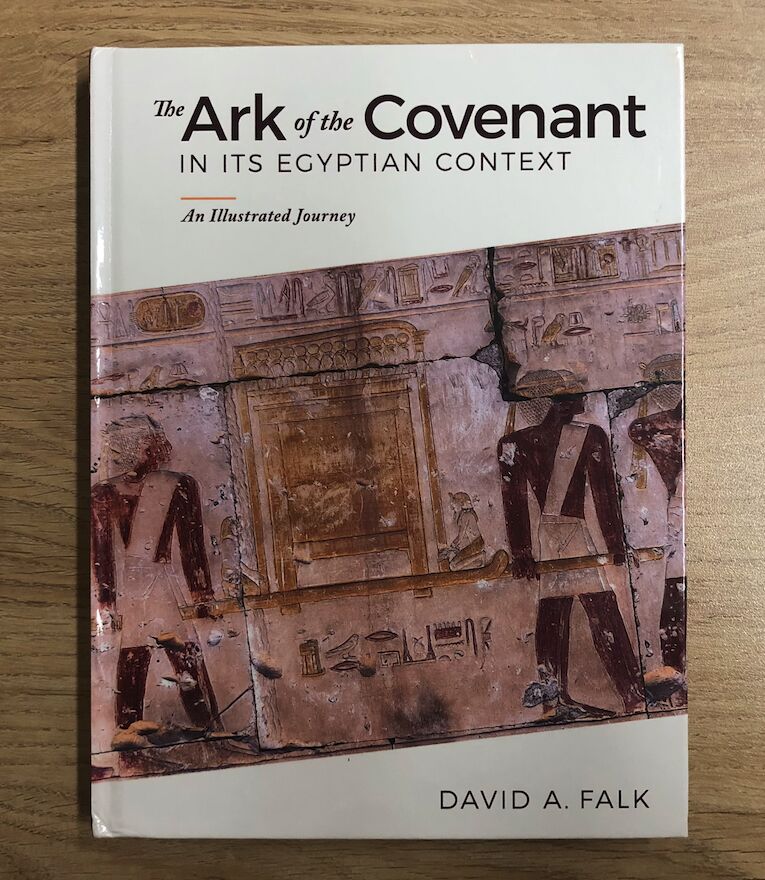

Egyptologist and Christian YouTube apologist Dr. David Falk is a staunch proponent of a 13th-century b.c.e. Exodus during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses ii. Naturally, he appeals to the argument that the number 40 is figurative. In his engaging book The Ark of the Covenant in its Egyptian Context, I came across an example I had never seen before:

Yet another example is the Mesha Stela (erected by the Moabite King Mesha, a contemporary of King Joram [circa 852–841 b.c.e.]) that ascribes a reign of 40 years to King Omri (circa 882–874) of the northern kingdom of Israel. But how can this be, since the Bible claims Omri reigned 12 years? (1 Kings 16:23). This should not come as a surprise since “40 years” was used to indicate an unspecified amount of time.

The Mesha Stele giving a 40-year reign to Omri? This was news to me. I had to re-read it to see what I had missed in previous readings. Such a drastically lower sum against Mesha’s “forty years” would indeed represent striking archaeological precedent for determining much lower counts for other periods. This would be an apt example of the number 40 as divorced entirely from reality—not just reflecting the rounding of a ballpark figure (i.e. a figure somewhere between 30 and 50).

Does the Mesha Stele say that King Omri—who, according to the Bible “reigned twelve years” (1 Kings 16:23)—reigned 40 years?

Short answer: No.

Long Answer

The Mesha Stele is one of the most remarkable and celebrated artifacts in the world of biblical archaeology. It is effectively 2 Kings 3 written from the perspective of the Moabite king Mesha, asserting his authority over the kingdom of Moab after a lengthy period of Israelite domination.

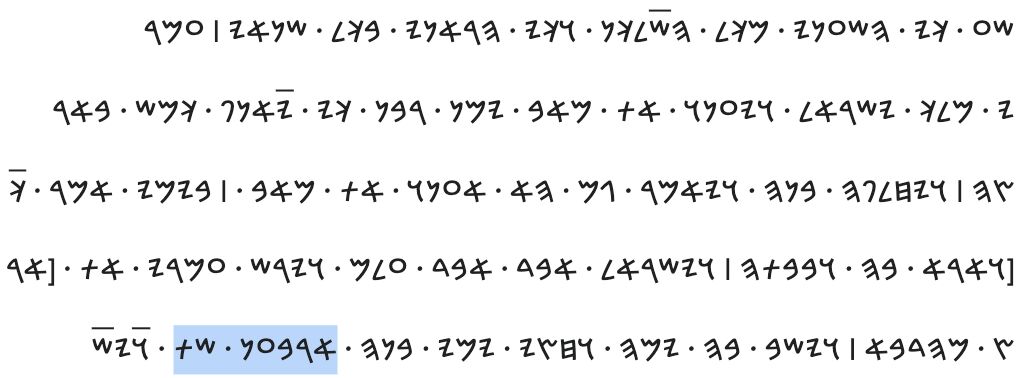

The following translation of the part of the stele in question is one that is popularly cited from James King (Moab’s Patriarchal Stone). The key section in question italicized:

Omri was king of Israel and oppressed Moab during many days, and Chemosh was angry with his aggressions. His son succeeded him, and he also said, I will oppress Moab. In my days he said, Let us go, and I will see my desire upon him and his house, and Israel said, I shall destroy it for ever. Now Omri took the land of Medeba and occupied it in his day, and in the days of his son, 40 years.

This is the only place in the inscription’s 34 lines where “40 years” appears. And far from it “ascrib[ing] a reign of 40 years to King Omri,” we encounter something entirely different: The stele states that the 40-year period applied not only to Omri, but also to his son.

From the biblical account, we know Omri’s son, Ahab, continued to exert control over Moab throughout the entirety of his reign, with Mesha’s uprising occurring partway into that of his own son, Jehoram (2 Kings 3:5). Ahab reigned 22 years (1 Kings 16:29). If we add this to Omri’s 12 years, we have a total of 34 years—a figure that quite justifiably could have been rounded off by Mesha as a period of about “40 years.”

So where, then, did this claim come from—that the Mesha Stele gives Omri’s reign as 40 years? Could it be a case of questionable translation of this passage of text on the stele?

Sort of, but here things get even more curious.

Even More Exact?

Despite the popular reference to King’s text, it is a translation of the stele that is sorely outdated (his book having been published in 1878). Falk himself references another: Following this sentence stating that the Mesha Stele “ascribes a reign of 40 years to King Omri,” a citation is provided—page 137 of The Context of Scripture: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World, Vol. ii (2002). Here we read the following translation provided by K. A. D. Smelik:

Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, for Kemosh was angry with his land. And his son succeeded him, and he said—he too—“I will oppress Moab!” In my days did he say [so], but I looked down on him and on his house, and Israel has gone to ruin, yes, it has gone to ruin for ever! And Omri had taken possession of the whole la[n]d of Medeba, and he lived there (in) his days and half the days of his son, 40 years ….

Once again, in no sense do we have the Mesha Stele ascribing a 40-year reign to Omri. But we do have a slightly different rendering at the end of our passage in question—“half the days of his son” (a common modern reading of this section of text).

There’s more, though—Smelik does not think this applies to Omri’s son Ahab, but rather Jehoram, his grandson (which in Hebrew and Moabitic can equally be rendered the same way, as “son”)—this Jehoram, again, during whose reign specifically the Bible states that Mesha broke away. Smelik provides the following footnote to this section: “[I]t is more probable that Omri’s grandson Jehoram (ruled 851–840 b.c.e.) is meant.” The identification of this particular “son” of Omri’s as his grandson—based on a comparison of the stele with the account in 2 Kings 3—is a common one.

Here we return to our calculations, using simple arithmetic based on total regnal sums (something perhaps also done by the scribe of the Mesha Stele?). Again, Omri and Ahab reigned 12 and 22 years, respectively—thus 34 years. Jehoram “reigned twelve years” (2 King 3:1). In the case of this translation provided by Smelik (and other modern translations like it), if we are to take “half” the 12-year reign of Jehoram and add it to our total … et voilà! 40 years.