The Assyrian Military Camp at Lachish—and Maybe at Jerusalem Too: An Interview with Stephen C. Compton

The invasion of Judah by King Sennacherib and the Assyrian army in the late seventh century b.c.e. is one of the most dramatic accounts in the Bible. It’s a story of barbaric torture and widespread regional destruction, as well as sudden, providential deliverance.

By the time the Assyrian juggernaut encamped by Jerusalem, it had already sacked 46 fortified Judean cities. Remarkably, the capital city escaped unharmed, a reality documented in detail in the biblical text, as well as Sennacherib’s own annals.

Archaeologically, Assyria’s invasion of Judah is one of the most well-attested biblical events in Near East antiquity. Giant wall reliefs, discovered in Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh (on display in the British Museum in London), record Sennacherib’s siege on Lachish. The Taylor Prism, discovered at Nineveh in 1830, records Sennacherib’s boast that he had “shut him [King Hezekiah] up like a caged bird in his royal city of Jerusalem.” In Jerusalem, Hezekiah’s snaking water tunnel attests to the king’s effort to defend Jerusalem; and two clay seal impressions attest to both King Hezekiah and Isaiah the prophet.

Researcher Stephen Compton published an article in the June 2024 issue of Near Eastern Archaeology outlining further evidence of Assyria’s invasion. In his article, Compton explained his discovery of a “trail of Sennacherib’s siege camps.” Compton identifies locations at Lachish, Jerusalem and elsewhere— this is the first time an Assyrian camp has been identified in Israel.

Compton’s article was front-page news at many international media outlets, including Fox News, the Daily Mail, the New York Post and Newsweek. In June, Brent Nagtegaal, host of Let the Stones Speak podcast, interviewed Mr. Compton about his research. The following interview has been edited for clarity.

Brent Nagtegaal (BN): Thank you for joining us. You have aroused some excitement in the media, even making global headlines. How did your interest in this history begin?

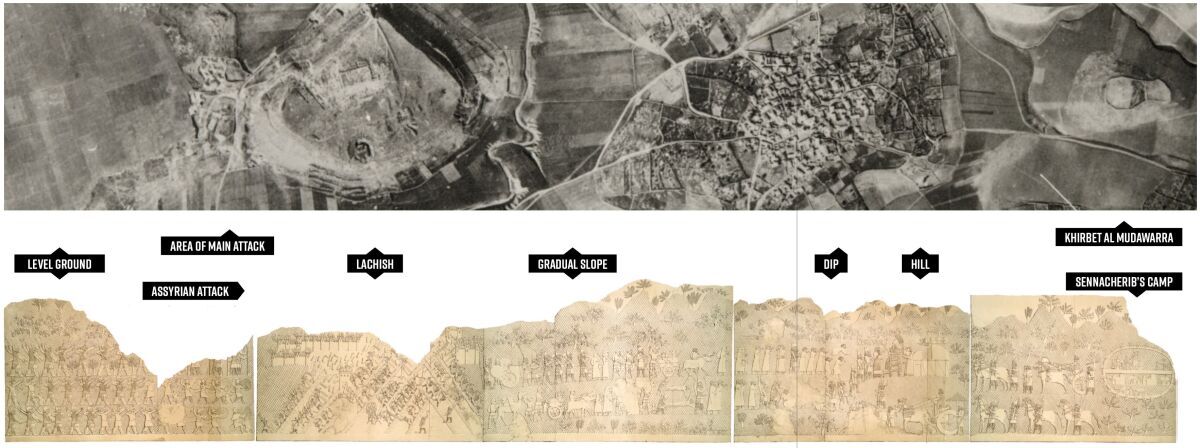

Stephen Compton (SC): I have long been fascinated by the Lachish site and the Lachish wall relief. On Sennacherib’s palace wall, he had this relief depicting his conquest of this city. On one side, it shows his army approaching the city; [Sennacherib] is up on a hill, and then in the distance you can see his siege camp. On the relief the siege camp is depicted by a large oval shape. So I decided to take Sennacherib’s relief image and compare it with the landscape of the area that exists today.

I found a 1945 aerial photo of the area, which I lined up beside the relief—and found that it was a very good match. I made the city [of Lachish] the exact same size in the relief as in the photo, so the scale was the same. On the one side, you have level ground to the left of the city. Then you have this gentle slope up to the right and this little hill, which is where Sennacherib himself sat, and then further to the right, Sennacherib’s oval camp. And at the same spot in the aerial landscape photo, there is an oval ruin.

I then decided to study the oval ruin and found that an archaeological survey had been conducted at the site. It showed some occupation in the Chalcolithic Period, but then it had been abandoned for 2,600 years before it was occupied by Lachish Level iii strata, which is the strata where the pottery marks Sennacherib’s invasion of Lachish. It was then abandoned again for centuries. The dating was a perfect match. So the shape, the size and its location were where they should be according to the relief. And in both cases, the long access was aligned to the city, both in the image and in reality.

BN: This is remarkable—the fact that these two scenes are almost identical. Who knew that the Lachish wall reliefs were actually drawn to scale? Can you describe what an archaeological survey is as opposed to an excavation, and what do you mean by Lachish iii?

SC: When a survey is conducted scientists do not excavate a site. Instead, they collect pottery sherds from the surface and use these to date the site’s habitation. They also identified oval-shaped fortification walls around the outside of this hill. More recently, farming at the site has made this lower fortification wall no longer visible above the ground.

The style of the broken pieces of pottery discovered in the survey were consistent with Lachish Level iii, which is the third-level strata of the city of Lachish. Those specific pottery sherds are found in the destruction layer of the site where there is evidence of a fire, wall destruction, iron arrowheads and a huge ramp coming up the site—all evidence of the Assyrian invasion of Lachish.

BN: So the discovery of both pottery as well as the fortification wall—and the clear dating of both to Sennacherib’s siege of Lachish—strongly indicate that this was the Assyrian camp. Now how does this oval-shaped fortress relate to Jerusalem?

SC: Well, I also studied early aerial photographs of Jerusalem. And to the north of the city, I found another oval structure of similar size and position [to the one outside Lachish].

BN: What do you mean by similar size?

SC: It was about 140 meters in length. It was almost the exact same length as the Lachish camp.

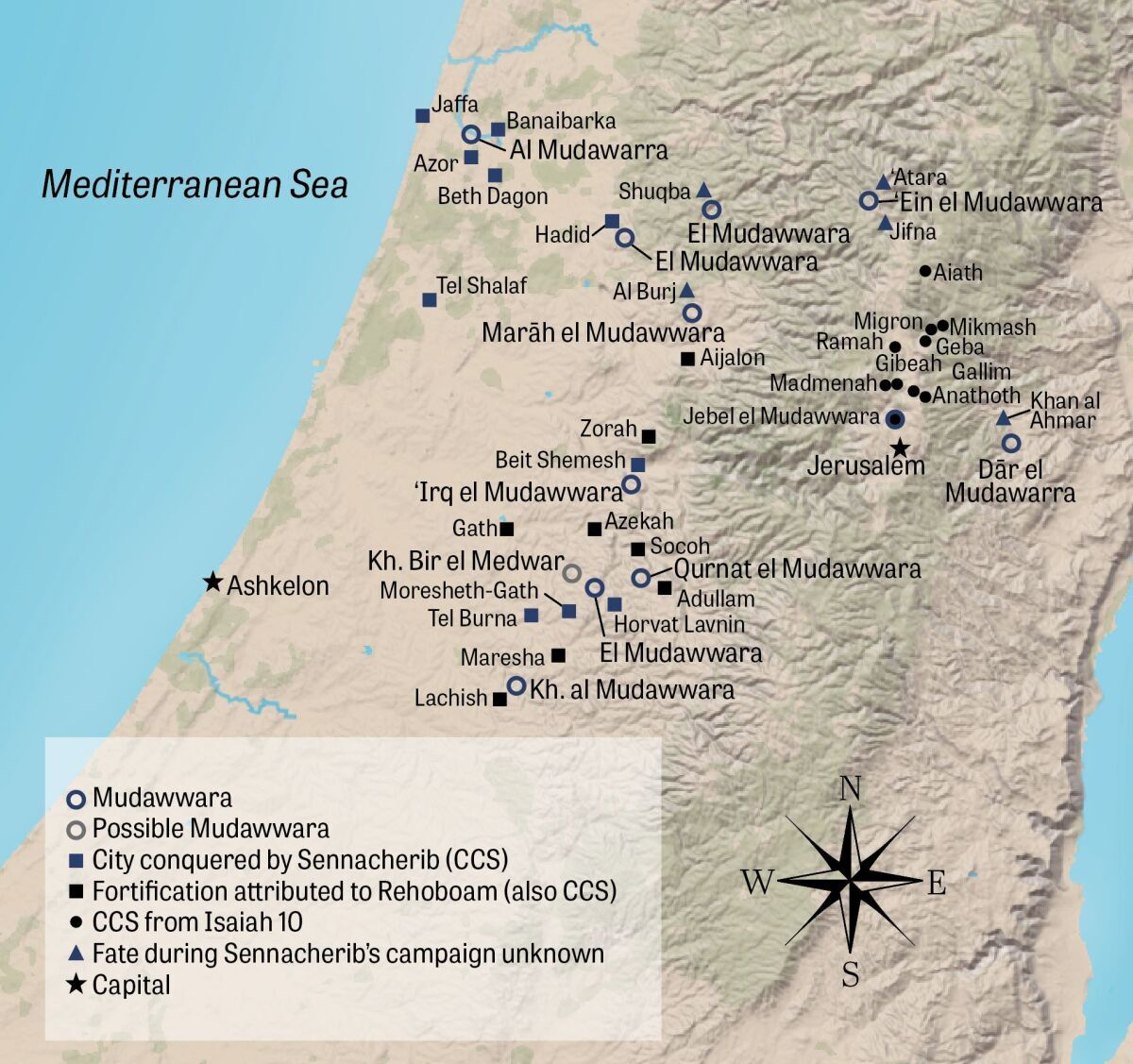

There was also another interesting feature. On early topographical maps [produced by the British], the Lachish camp site was labeled “Mudawwara,” an Arabic name. In the Middle Ages, this name was used to identify the “camp of an invading sultan,” so mudawwara could mean something like the “camp of the invading king.” So, it is a reference to some sort of royal camp. I noticed that the Jerusalem site also had the same name—mudawwara.

In 1881, the Palestine Exploration Fund went to the oval site in Jerusalem and identified it as a military siege camp, but they thought it was the camp of Titus from 70 c.e. However, we now know that the Roman camps were rectangles and this is clearly an oval shape, which is the characteristic shape of an Assyrian military camp.

We don’t have an archaeological survey as we do at Lachish, so the evidence isn’t as strong. But we have the same name, the same size, the same shape and the same position, which is on the north of Jerusalem. And the biblical text, in Isaiah 10, records that the Assyrians approached Jerusalem from the north.

BN: Tell us more about the passage in Isaiah 10, which records that Assyria was the “rod of [God’s] anger.” This seems to connect with your Assyrian camp near Jerusalem. Why is this significant?

SC: There has always been some controversy over Isaiah 10. Some researchers said that it could not be talking about the Assyrians because, according to them, Sennacherib went from Lachish to Jerusalem, approaching Jerusalem from the south. Why would he approach from the north? But I followed the route of other mudawwara toponyms that were all located about a mile from cities we know Sennacherib conquered, and it indicates that from Lachish the Assyrians went north on the diagonal route well past the latitude of Jerusalem before turning east and then south and approaching Jerusalem from the north.

This is consistent with the approach recorded in Isaiah 10, where it says Sennacherib approaches a certain city, then another city, and then he finally ends up at Nob. This appears to be where he made his camp. Which is also an exciting coincidence because it says he halts at Nob. [“This very day shall he halt at Nob, Shaking his hand at the mount of the daughter of Zion, The hill of Jerusalem”—verse 32.]

Sennacherib makes his stand at Nob, which seems to be where his camp is, and if so, it gives us the location of Nob. Nob was the place where the tabernacle was at the time of Saul and David, and when David fled from Saul he fled to Nob and was given some assistance there. Saul becomes enraged and has genocide committed against Nob. Nob is not heard from again until this passage in Isaiah, 300 years later, when the Assyrians approach and make their stand there.

BN: In your article you note that there are several ideas about the exact location of Nob. And your suggestion that the Assyrian army camped in Nob puts the city right in the middle of where the other potential locations are.

SC: Yes, it is on the road from Gibeah, which is where King Saul’s capital was located, to Jerusalem. It is right in the middle. And I think the passage dealing with Saul and David indicates it is close to Gibeah. But the account in Isaiah 10 indicates it is also close to Jerusalem. And this location is on the main northern road out of Jerusalem right in between both cities.

BN: You are obviously drawing a connection between the medieval Arabic name Mudawwara and the sites that King Sennacherib attacked. But there is a gap of more than 1,000 years between the toponym name and the event of the Assyrian invasion. How sure can we be of the connection between mudawwara and a camp of Sennacherib’s army?

SC: My theory is that this was a major local event and there would have been the physical structures that remained, and there would have been local knowledge of it. For example, “That’s the camp from when the Assyrians invaded—the camp of the invading king.” And so the name just kind of stuck with them over time and the traditional knowledge sort of survived in this toponym.

BN: And this isn’t without parallel; we have other sites where Arabic names preserve the name of a site from biblical times. So you are really drawing on every bit of evidence you can for this. Did you receive any feedback from scholars about your theory?

SC: I received some pushback about Isaiah 10 because some scholars don’t believe Isaiah 10 is referring to the Assyrians. I think if there hadn’t been the certain assumption that Assyria approached Jerusalem from the south, nobody would have questioned that Isaiah 10 refers to the Assyrians. There was just the assumption that “We know best. We know the route they took. Therefore, we have to find another explanation.” But the passage is very clear in mentioning the Assyrians. I think trying to put another invader in Isaiah 10 is misguided.

There has been a lot better response to the Lachish camp because there is so much evidence. I think when you see all the evidence it is hard to push back on. [Archaeologist David] Ussishkin disagrees. He has his own theory, and I respect that.

BN: Even before your research, Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah during the time of Hezekiah was incredibly well attested by archaeology. And now, thanks to your efforts, we have even more evidence of this event. Now we have evidence of Assyrian camps—definitely at Lachish and quite possibly at Jerusalem—in precisely the locations identified by the Bible. Thank you so much for your research and sharing this with us!