Seeking Solomon: United Monarchy on the High Seas

When I started diving off ancient Dor, I found myself immersed in one of King Solomon’s legendary havens. What could be more historic, more romantic than exploring waters where the wise king’s ships once docked? On land the city had a four-chambered “Solomonic” gateway. Surely many of the stone anchors we lifted from the southern harbor were boat breaks used in the iconic 10th-century too? Decades later I’ve found Solomon, not in Israel but on the ancient equivalent of the far side of the moon, Tartessos in Spanish Andalusia.

Solomon was a judge, soldier, scholar, composer and shipping magnate. His words and wisdom are legendary. The king handed down new case laws from Jerusalem’s palace and is credited with 3,000 proverbs. His sayings live on today: Love is sweeter than wine, there is nothing new under the sun, and pride goes before a fall. Jewish folklore insists Solomon invented chess. Arab chroniclers honor him as the inventor of coffee.

In the 21st century, Solomon is still a household name. More people are married to the “Arrival of the Queen of Sheba” from Handel’s 1748 Solomon oratorio than to Bruno Mars’ “Marry You” or “Over the Rainbow.” In medicine, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome treats the placenta using the Solomon technique. Solomon the magician weaves heroic spells in Japanese manga cartoons. Streets, hotels, banks, casinos and kebab shops the world over carry into the future Solomon’s name and the ideal of wisdom, wealth and luck.

Just how much of Solomon’s stellar biography can be tracked back to a monarch who ruled Jerusalem in the 10th century b.c.e.? King Solomon’s true identity laughs at us behind the great firewall of biblical archaeology.

Bible, Pick and Spade

As the starting blocks for exploring the bricks and mortar of the Bible in the mid-19th century, archaeology ushered in a new scientific dawn. By way of just one example, in the deep south of the Bible lands the American rabbi, archaeologist and president of the Hebrew Union College, Nelson Glueck, started picking back the soils of Tell el-Kheleifeh in Eilat on the northern shore of the Red Sea in 1937. What appeared beneath the surface seemed a perfect fit for Ezion-geber where Solomon built a fleet of ships to set off and trade with the lands of Ophir and Tarshish for gold, silver and exotic riches. Despite lying in the middle of nowhere, the ancient site was surrounded by a serious piece of security with 8-meter-high (26 feet) walls fronted by an imposing four-chambered gate and dry moat facing the sea. The defensive circuit was more suited to a city 10 times as big. What were its defenders protecting?

The settlement at el-Kheleifeh was built on a hill rich in iron and copper, ideal for smelting and refining metal. A state-of-the-art smelter refinery, designed with flues and air channels to harvest the sea winds—hence the site’s hostile coastal location—were found stained green from 3,000 year-old copper sulphide fumes.

Nelson Glueck was convinced he’d unearthed the “Pittsburgh of Palestine,” a city strengthened near the end of the 10th century b.c.e. after being attacked, probably by the Egyptian Pharaoh Shishak. The new Ezion-geber continued casting copper and iron into the reign of Jehoshaphat of Judah in 873–849 b.c.e. To Glueck, the ancient forensics fitted just one identikit ruler:

There was, so far as we know, only one man who possessed the strength, wealth and wisdom capable of initiating and carrying out the construction of such a highly complex and specialized site as this Ezion-geber. He was King Solomon. He alone in his day in Palestine had the ability, the vision and the power to build an important industrial center and sea-port so comparatively far from Jerusalem. … The wise ruler of Israel was a copper king, a shipping magnate, a merchant prince and a great builder.

Over the Horizon

Where archaeologists have fought themselves to a standstill with few ruins left to test time in Israel, nobody has peered over the horizon and into the ocean deep. The Bible immortalizes Solomon as the nation’s first shipping magnate. Building cities, palaces, stables and a flagship temple didn’t come cheap. If true, the king must have controlled and taxed far-flung agricultural lands to cover the costs of his maritime schemes. Long-distance voyages to the land of Ophir and Tarshish, shoulder to shoulder with his joint venture partner, the Phoenician king Hiram of Tyre, brought a river of gold, silver, copper, peacocks, ivory, monkeys, precious stones and marble to the royal court until “King Solomon excelled all the kings of the earth in riches and in wisdom” (1 Kings 10:23).

The Phoenicians were a sea people with a big reputation, famously roaming the high seas in search of profit. Their artistry played a key role in landscaping a sparkling Jerusalem. Solomon and King Hiram, who ruled over Tyre in modern Lebanon from around 971–939 b.c.e., and whose people were “the bestower of crowns, whose merchants are princes, whose traders are renowned in the earth” (Isaiah 23:8; niv), enjoyed history’s first special relationship. They exchanged luxuries as tribute and through a bond of trust made their cities run with rivers of silver and gold.

Neither Israel nor Lebanon could tap into local gold and silver mines to secure their ultimate status symbols. So how did Solomon make “silver as common in Jerusalem as stones, and cedar as plentiful as sycamore-fig trees in the foothills,” as the book of 1 Kings put it? For the source of gold and silver lining the temple’s walls, inner sanctuary and altar that made Jerusalem shine under eastern skies as a reflection of God’s glory, the biblical entrepreneurs were forced to look over the horizon.

The land of Tarshish was a vital source for Solomon’s silver. As the book of Ezekiel recorded, “Tarshish did business with you because of your great wealth of goods; they exchanged silver, iron, tin and lead for your merchandise. … Judah and Israel traded with you; they exchanged wheat from Minnith and confections, honey, olive oil and balm for your wares. … The ships of Tarshish serve as carriers for your wares. You are filled with heavy cargo as you sail the sea” (Ezekiel 27:12, 17, 25; niv).

Solomon and Hiram’s trade needed a safety network of well-run ships, coastal havens, warehouses and workshops. By exploring the maritime trail beyond the Bible lands and beneath the ocean’s incorruptible waves, the shouts of angry academics fall silent and a rare resource rises—truth.

The lost mining frontier of Tarshish has been signposted wildly from southern Israel to the Red Sea, Ethiopia, India, Africa and Carthage in Tunisia. A fusion of texts and ruins points to a far more conclusive candidate, however. Tarshish was a destination far from Israel. It was to this distant shore that Jonah fled from Joppa in Israel to escape God’s all-seeing eye. The Assyrians also understood Tarshish to lie at the ends of the world.

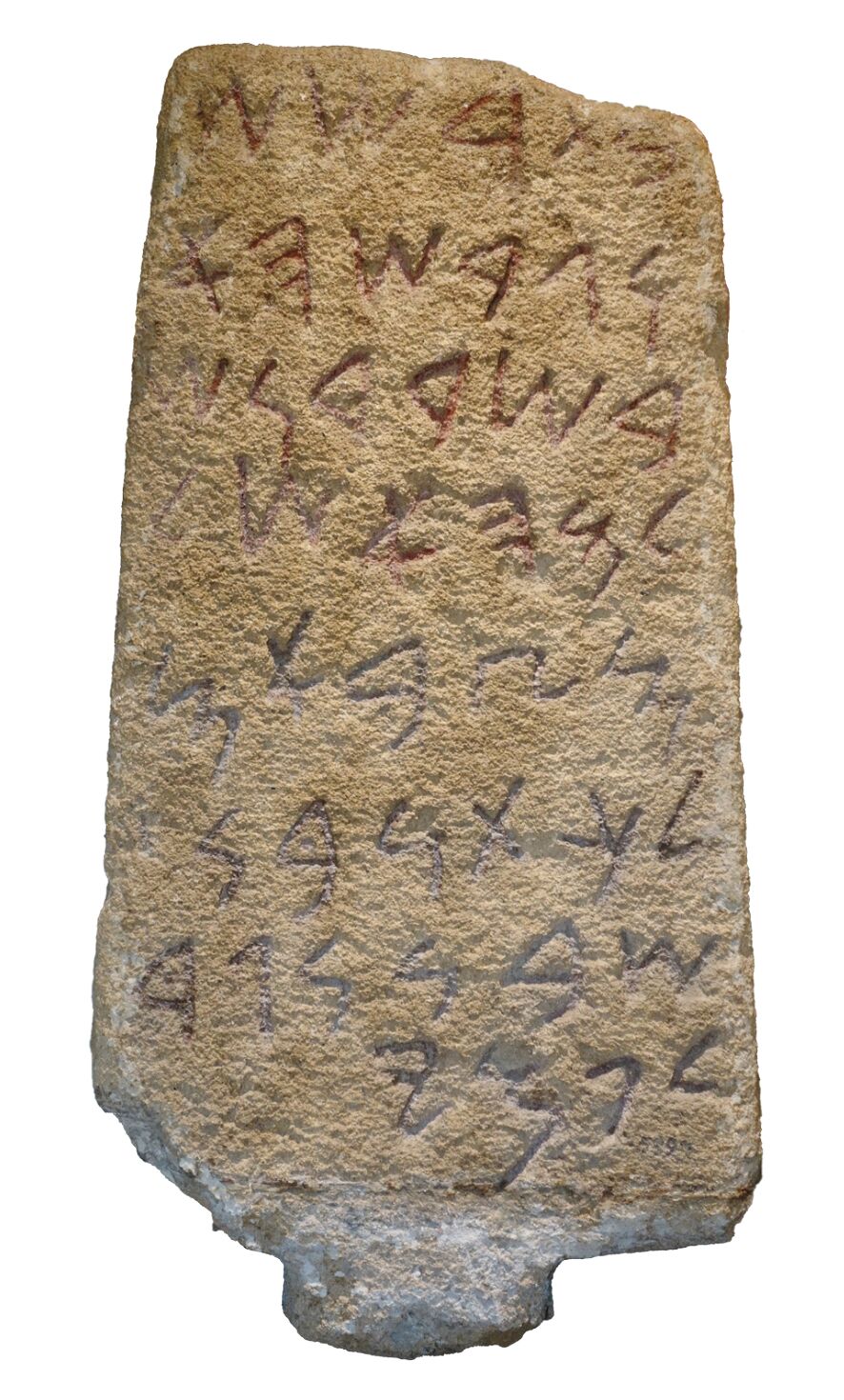

This was no epic myth-making. A meter-tall limestone inscription dug up in the ruins of Nora on Sardinia proves that Tarshish was grounded in geographic reality. An eight-line Phoenician dedication commemorates how, after defeat in battle, a military force commanded by an officer called Milkûtôn escaped by ship to Sardinia from Tarshish, where his soldiers lived out a peaceful life. Tarshish, then, lay close to Sardinia in the early ninth century b.c.e. when this calling card was committed to stone.

Tarshish must also correspond to a land where Near Eastern cultural remains and extensive signs of ancient mining overlap. Just such a unique combination converges on the southern Iberian Peninsula in an area known in antiquity as Tartessos, a Greek derivation of Tarshish. Diodorus of Sicily linked Solomon’s Tarshish to Iberia in his universal history, the Bibliotheca Historica, where “[t]he country has the most numerous and excellent silver mines …. The natives do not know how to use the metal. But the Phoenicians, experts in commerce, would buy this silver in exchange for other small goods. Consequently, taking the silver to Greece, Asia and all other peoples, the Phoenicians made good earnings.”

Rivers of Silver

Tarshish was a frontier with bottomless precious metal. Solomon and Hiram’s joint ventures involved a grand blue-water vision risking life and limb a world away from the bustling Orient. Wind power and sailing prowess had to navigate over what for the early Iron Age was a challenging 5,200 kilometers (3,200 miles) of water from the safety of Jerusalem. To these pioneering sailors, Tarshish was the far side of the moon.

After reaching Spain and sailing a further 75 kilometers (47 miles) upriver from Cadiz, the intrepid ancient explorer reached King Solomon’s own El Dorado. Undulating volcanic hills rise 530 meters (1,700 feet) across the Sierra Morena above one of Europe’s richest olive and wheat belts. Beneath the pine-perfumed slopes, a swathe of pyritic minerals stretches 150 kilometers (90 miles) in length and 30 kilometers (20 miles) in width between Seville and Lisbon. The epicenter of these divinely blessed ores is the Colored River, or Rio Tinto in Spanish. It was what was buried under these mountains that inspired Solomon and Hiram to hedge their bets crossing the stormy Mediterranean.

Rio Tinto is the largest mine exploited in antiquity. Down the centuries its deposits yielded 6 million tons of precious metal. Ores contained in a 6-meter-deep (20 feet) layer of argentiferous clay contained every heavy metal a king could wish for: gold, silver, lead, copper and zinc. The extraordinary deposits yielded up to 3.1 kilograms (6.8 pounds) of silver per ton. Israel and Phoenicia, Rome and Colonial Spain left behind their tell-tale signs of industrial exploitation in 18 million tons of sprawling slag heaps.

Ancient texts, inscriptions and abandoned wooden waterwheels leave no doubt that Rio Tinto was a star attraction that inspired Rome to seize the province of Felix Baetica, Happy Baetica. Seeking Solomon and his partners a thousand years earlier, in an age that left behind no official paperwork, requires a leap of faith though—at first glance.

Local legend bridges the divide between myth and reality. In the year 1629, Signor A. Carranza was struck by impressive signs of very early ancient mining:

[W]ithin sight of the Rio Tinto (with its wondrous waters, which feed no fish nor living thing but on the other hand are greatly salutiferous) there is an isolated stretch of high land of circumference of four leagues. Halfway up its flanks, a third or quarter of its height, there are many openings and mining tunnels like a rabbit warren. On the lowest level of these there are almost countless numbers of shafts that still remain today … with many tunnels and deep caves, which are driven deeply in from the high land.

On his map, Carranza inscribed the local name of this rich mine—Solomon’s Hill—and noted that even earlier the landmark was called Solomon’s Castle. The memory of Solomon and ancient mining was alive and well in 1634 when Rodrigo Caro’s Antiguedades y Principado de la Ilustrisima Ciudad de Sevilla described how “[t]he inhabitants of those parts have a tradition (so they say) that the people sent there by King Solomon for gold and silver built it [Zalamea la Vieja] and gave it the name Salamea. As proof of this they pointed out that a very old castle that is nearby has been called ever since that time the Old Castle of Solomon.”

Today, not just the castle but the entire hill of Cerro Salomon has been razed to the ground, layer after layer pulverized by modern industry. The scarred stub of Solomon and Hiram’s journey’s end are isolated in a barren industrial landscape criss-crossed by abandoned wooden railway beams. Sulphur chokes the air. Pools of mineralized river water the color of curdling blood lick the hill’s slopes. The scene is less seeped in great antiquity than resembling a surreal film set for a dystopian blockbuster, more Mad Max than King Solomon’s mines. With Solomon’s Hill ground to dust by the bulldozers, how can science sieve truth from legend?

Before leveling Solomon’s Hill, Spanish, Israeli and English archaeologists had a chance to check what lay below. As the soils were peeled back, an ancient frontier mining village came to light. A settlement straddled the top of the 515-meter (1,700 feet) hill, while ore was dug out from mining galleries opened in the lower slopes using stone hammers and picks. Fresh spring water at the bottom of the hill gave refreshing relief for the miners and villagers and was essential for refining the metal.

The village once covered 900 meters (3,000 feet) of hilltops. Its rectangular houses were divided into small rooms with slate floors and built from undressed dry stones covered with light thatched roofs. The foundations were found stuffed with abandoned mining equipment: granite pestles and stone mortars used to crush minerals, slag, charcoal, droplets of lead and casting pipes. The miners lived cheek by jowl with silver-refining workshops. The lead slag excavated from Solomon’s Hill held a high proportion of silver, 575 grams (1.3 pounds) per ton. But what of the ruins’ date and origins?

Costa del Phoenike

Far from Tyre and Solomon’s Jerusalem, familiar Phoenician pottery abounded in the frontier village on Solomon’s Hill: globular amphoras, saucer-shaped oil-lamps, oil jugs and tripod-shaped containers. The link between the Near East and Solomon’s Hill is certain from Phoenician amphora sherds fused to grey lead and silver slag. As much as 30 percent of the mining village’s pottery turned out to be Near Eastern imports. Cerro Salomon—the Hill of Solomon—was a Phoenician village in Tarshish occupied seasonally to coincide with regular voyages from the Near East. The earliest houses were built in the late eighth-century b.c.e.: early but still later than the traditional 10th-century date of King Solomon’s reign.

The Andalusian port of Huelva commands the end of a riverine drain where the Rio Tinto discharges its bloodred waters into the sea. In an ironic twist of Spanish history, all the while Columbus circumnavigated dangerous lands beyond the rim of the known world, Spain’s first great El Dorado could have been tapped only a couple of days’ journey upriver under Solomon’s Hill. Huelva and Spain’s very own “Golden One” were also physically linked by water.

Ancient ruins dug up across 2,145 square meters (23,088 square feet) of the heart of Huelva’s city center in the last decade have confirmed a widespread Near Eastern mercantile presence in Iberia and are pushing the date of contact with these silver lands ever deeper back into biblical times. The Plaza de las Monjas looks like an improbable Ground Zero for the land of Tarshish. The Bank of Spain and Deutsche Bank rub shoulders with schools of English and the Good Burger Bar. Down the road, the Hotel Eurostars Tartessos tips its hat at the founders of the town’s ancient fame. The first-story offices of Detectives Privados help distressed clients uncover unwanted truths. A life-size bronze statue of Christopher Columbus guards the entrance to the plaza, pointing his finger west, far off toward the Americas.

Some 3,000 years ago, Huelva’s central square was a cosmopolitan coastal souk. Deep deposits of pottery imported from across the Mediterranean lie entombed beneath modern paving stones, including the finest ceramics of Sardinia, Italy, Greece and Cyprus. Most of Huelva’s ceramics, however, came from the Phoenician homeland: No less than 40 percent of the pots and pans resemble products from Tyre. Signature Phoenician culture was found scattered alongside: an elephant tusk, ivory waste and finished art, murex seashells harvested to make purple-dye, weaving equipment, parts of ship hulls and half-shekel, one-shekel and three-shekel merchants weights relied on to buy, sell and ensure Near Eastern and Tartessians didn’t rip off one another.

To complete the scene of bustling maritime commerce, signs of metalworking litter the ancient ruins—bricks from furnace walls, crucibles for copper founding, slag and sandstone molds for casting. Huelva’s rich ruins make this city the best fit for the capital of Tartessos and the biblical Tarshish. The refuse of the ages beneath the statue of Columbus in the Plaza de las Monjas places the appearance of the Israelite and Phoenician maritime venture at Huelva close to the year 900 b.c.e. and perhaps as early as 930 b.c.e., the end of the reign of Solomon. Just as the ancient sources claimed, Tarshish lay on the far side of the Mediterranean, close to the Pillars of Hercules in the Straits of Gibraltar that marked the end of the civilized Mediterranean and start of the cruel Atlantic.

The new maritime trail changes everything. The ambivalence that came close to giving up on the Bible and tarring the Old Testament narrative of Solomon and Hiram of Tyre as a fabulous invention has been turned on its head. Solomon, Hiram of Tyre and Tarshish have shifted from a Dark Age fantasy to a brave new credible world. Archaeology has revealed a Phoenician coast stretching from Huelva in the west to Alicante in the east, with the Tyrian colonies at Morro de Mezquitilla, Almuñécar, Chorreras, Toscanos, Adra and Cerro del Villar at Malaga rivaling the Costa del Sol 28 centuries earlier. The Near Eastern merchant venturers planted and hoisted their flag over a “Costa del Phoenike” at least by the second half of the ninth century b.c.e.

The Old Testament was right in its broad-brush strokes. There’s every reason to believe that a King Solomon existed, arm in arm with his Phoenician friends. The archaeological evidence points to Solomon and his court leaning on Hiram’s Tyrian masters of the seas to manage the seafaring voyages. And Jerusalem put up the cash.

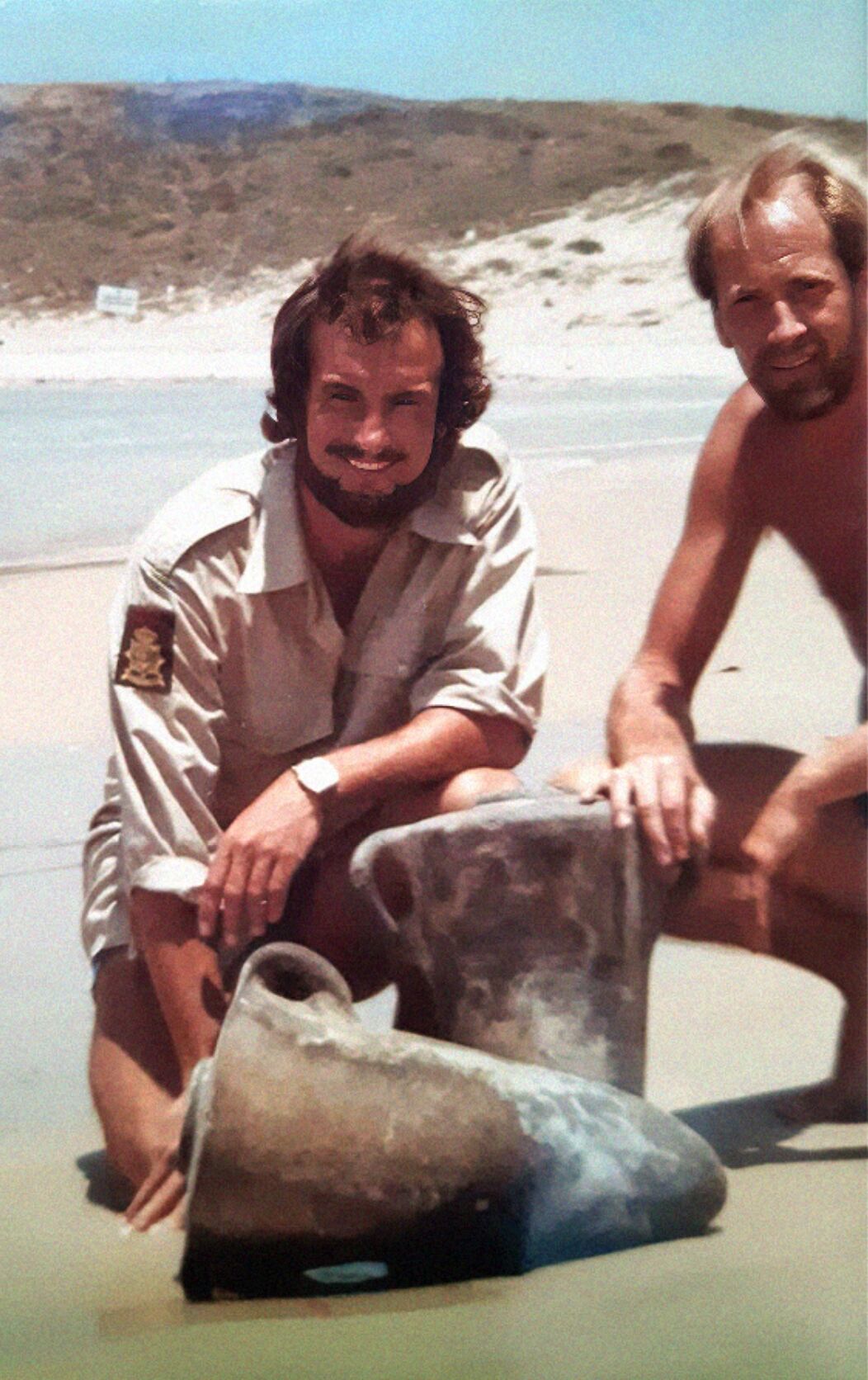

The one glitch in this new grand vision of Solomon and his Phoenician allies are the missing wrecks. Were Tyrian sailors so good that they managed to avoid being wrecked? This is unlikely. Lost ships with Phoenician cargoes have turned up at Mazarron and Bajo de la Campana off Spain, Gozo in Malta, Kekova Adasi in Turkey and in deep waters off Asheklon, Akko and Atlit in Israel. All cluster no earlier than between 750 and 600 b.c.e., though.

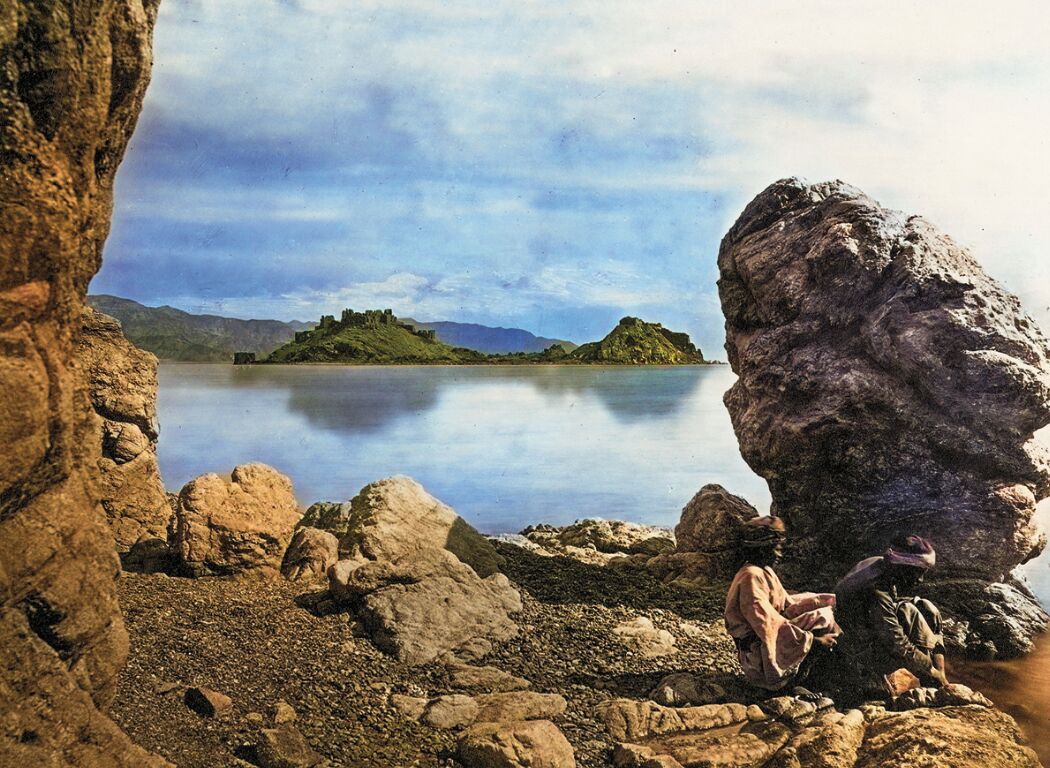

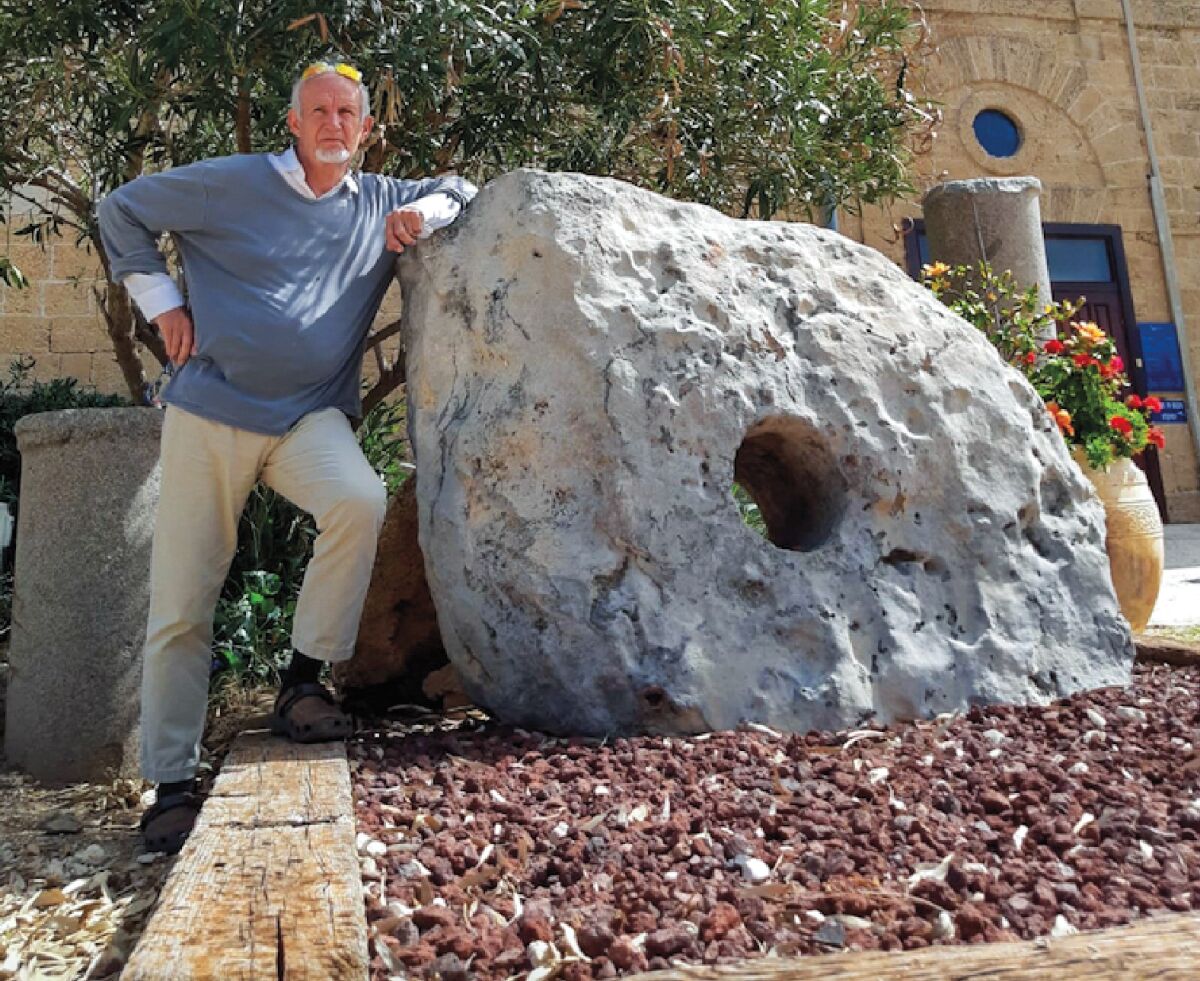

Back where diving for Solomon all started for me at Dor in Israel, there’s a twist in the tale—literally. Kurt Raveh, a marine archaeological expert, was walking his dog along the southern shores, opposite an islet long named after Taphath, the princess daughter of King Solomon, when Petal stopped swimming and suddenly walked on water. A miracle! When Kurt checked what his dog was standing on, he found what looked like a gigantic stone anchor, 2.5 meters (8 feet) long and 50 centimeters (20 inches) thick.

An even bigger surprise turned up under the anchor. Buried in the sand, Kurt discovered large wooden beams, possibly part of a ship’s keel. Most of the dozens of wrecks in this ancient harbor are Byzantine and Ottoman. Astonishingly and unexpectedly, the radiocarbon results from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich came back with a reading of 997-806 b.c.e. The anchor and wood overlapped with the reign of King Solomon.

Now Kurt wants to know if the timbers are random beams or if the first shipwreck from the time of King Solomon is waiting to be dug up off Dor. And so does the rest of the world. Long live the king.

Dr. Sean Kingsley is the editor in chief of Wreckwatch magazine and wreckwatchmag.com. In his more than 30 years as a marine archaeologist and historian, he has authored 15 books and explored more than 350 shipwrecks. In addition to Wreckwatch, he also writes for Smithsonian magazine.

Some of his deep sea explorations have been concentrated on the waters of the east Mediterranean off the coast of Israel. His maritime activities have given him a unique understanding of ancient civilizations, as evidenced in this article.