Shaming the Name (Quite Literally): From ‘Baal’ to ‘Bosheth’

A “theophoric” name is one associated with a deity (“theo” meaning “god” in Greek). The part of the name reflecting that deity is called the theophoric element. These names are common in the Bible: An example is Yah or Yahu, an abbreviation of Yahweh/Jehovah—as in Jeremiah, Hezekiah, Jehoshaphat. Another is El/Elohim, as in Daniel and Samuel. Some names even combine both forms, such as Joel and Elijah. Of course, this is not just limited to the Bible—there are numerous other such theophoric names around the world for different deities. There’s a good chance your name contains a theophoric element. Mine does.

But even in the Bible, such theophoric names are not limited to the God of Israel. Numerous names contain pagan theophoric elements. One of the most infamous deities of the Bible was Baal. Therefore it should come as no surprise that this name, too, was a common name element.

Yet Baal name elements actually aren’t, at first glance, as obviously ubiquitous in the Bible as they really were at the time. There’s a good reason for that: In several instances, this common theophoric element was actually deliberately changed to something else entirely.

And there’s an interesting archaeological angle to this story, too.

Shaming the Name

The primary case in point is the family of Saul. One of his sons was Ishbosheth, who took the throne of the northern tribes of Israel for a brief two years following his father’s death (2 Samuel 2:10). Another was Saul’s grandson Mephibosheth (2 Samuel 21:8), a young man crippled in his legs following an accident at the age of five (2 Samuel 4:4), who later developed a close relationship with King David.

These individuals also bear other, less familiar names. They are listed in the book of Chronicles family trees as Ishbaal and Meribbaal (1 Chronicles 8:33-34; 9:39-40; note that Ishbaal is sometimes spelled “Eshbaal” depending on the translation). Ishbaal/Ishbosheth, Meribbaal/Mephibosheth—why the difference?

These are not the only examples. 2 Samuel 11:21 recounts an incident during the earlier judges period in which Abimelech the son of Jerubbesheth was killed. The original account, Judges 9:1, calls him Abimelech the son of Jerubbaal. And this same Jerubbaal, of course, was the judge Gideon (Judges 7:1).

It is clear that bosheth/besheth (Hebrew בשת) is a replacement for the theophoric element baal (בעל). The meaning of the latter, signifying the god Baal, is clear. (Judges 6:32 actually explains the reason for Gideon receiving this name, after an incident at a pagan place of worship: “Therefore on that day he was called Jerubbaal, saying: ‘Let Baal contend against him, because he hath broken down his altar.’”)

However, the word “bosheth/besheth” is a Hebrew word meaning shame or shameful thing.

The use of this element therefore becomes evident: This was a name element designated to obscure the name “Baal”—to cast shade on a name of pagan association. Thus Ishbaal, meaning “man of Baal,” became Ishbosheth, “man of shame.” Jerubbaal, meaning “let Baal contend,” or “Baal will fight,” became Jerubbesheth, “shame will fight.” The transformation from Meribbaal to Mephibosheth is a little more pronounced. A standard opinion for the meaning of Meribbaal is “Baal is my advocate,” or even as a name related to Jerubbaal, meaning “Baal contends.” Mephibosheth, on the other hand, with an additional slight change to the first part of the name, is offered to mean something like “he scatters shame.”

If this is the correct interpretation for the name Mephibosheth, then this would constitute a somewhat more positive twist of the name. This would be fitting, as Mephibosheth/Meribbaal, Saul’s grandson, was actually the son of Jonathan, who was famously benevolent toward and supportive of David throughout his life. The older Jonathan recognized David as the divinely chosen successor of Saul rather than himself, and he worked to counter his father’s attempts to have David killed. This may explain the more favorable name variant given to his son, as opposed to that of his brother Ishbosheth (“man of shame”), who did seek to establish himself as king over Israel.

As a side, in 1 Samuel 20:30, Saul rails against his son Jonathan using the same “shame” terminology. “Then Saul’s anger was kindled against Jonathan, and he said unto him: ‘Thou son of perverse rebellion, do not I know that thou hast chosen the son of Jesse [David] to thine own shame [besheth], and unto the shame [besheth] of thy mother’s nakedness?” A renaming of his son as Mephibosheth, meaning “he scatters shame,” would therefore be doubly significant.

Whatever the case, the original inclusion of the theophoric name-element baal, as highlighted by the Chronicles genealogies, opens up a fascinating window into the study of Saul’s family and their religious persuasion. After all, these are not the only such names found in the family with a link to the name Baal. Actually, one of Saul’s uncles was named “Baal” outright (1 Chronicles 8:30; 9:36). Recognizing such a background, then, can help add extra color to the biblical account of Saul’s rollercoaster reign—one that was ultimately catastrophic (with the king at times even identified as being demon-possessed—1 Samuel 16).

Archaeological Element

This religious melee within Israel at the time is highlighted by archaeological discoveries—particularly those related to this period in question (the end of the second millennium b.c.e.).

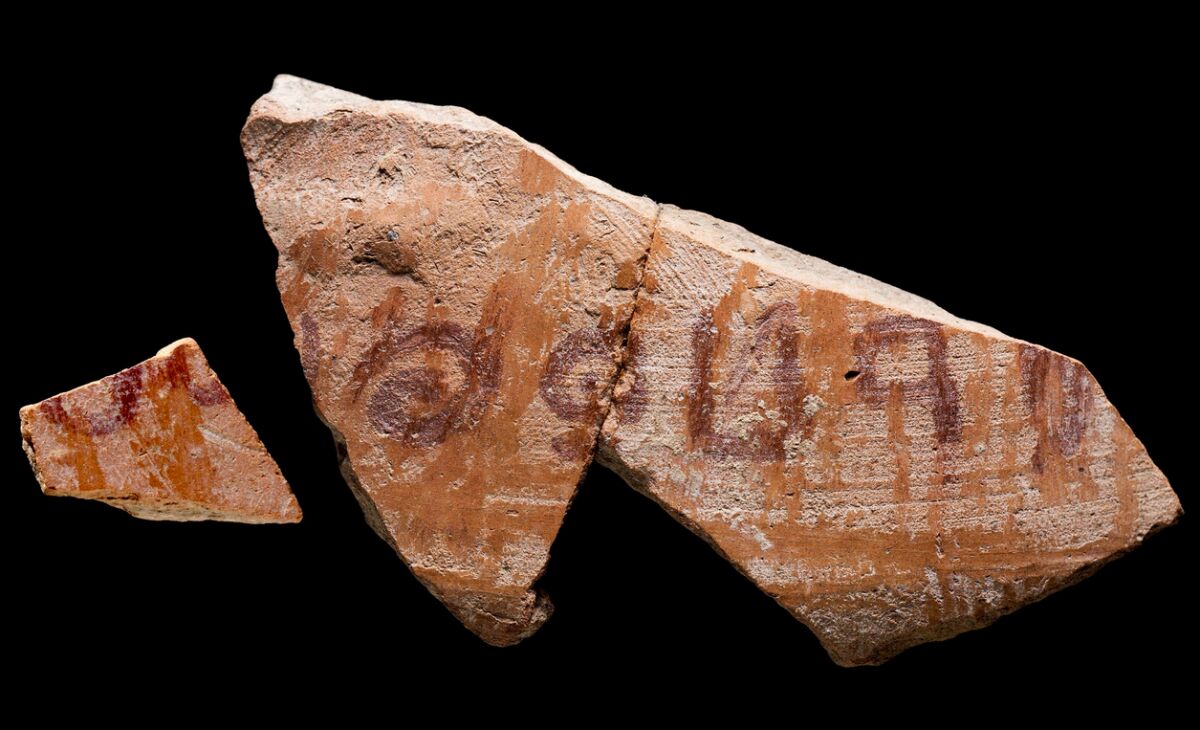

Remarkable evidence of the judge Jerubbaal’s name was found on a pottery inscription (ostracon) dating to the same general period as the biblical judge (end of the 12th century b.c.e.). Of course, it is impossible to confirm that this ostracon directly refers to one and the same individual, the judge Gideon. Still, as far as can be reasonably ascertained, the weight of evidence points to this conclusion (you can read more about the ostracon here). But whether or not it belonged to one and the same Jerubbaal, the presence of the name speaks to the widespread level of Baal worship on the scene at that time (as explained in the account of Gideon, whose own father was a Baal worshiper—see Judges 6).

The name of Saul’s son and (temporary) successor, Ishbaal, has also been discovered on a vessel from the Saulide/Davidic-era fortress, Khirbet Qeiyafa. The dating of Khirbet Qeiyafa is remarkably concrete, fitting within the same few decades as these biblical kings. Yet despite the discovery of this identical name from the same period, we can be certain that this Ishbaal was not Saul’s son. That’s because the inscription names another father: “Ishbaal, son of Beda.” While this may be disappointing to some, what this actually further hints at is the ubiquity of names containing the baal theophoric element—in this case, another “man of Baal,” Ishbaal.

These “men of Baal”—figuratively and literally—only corroborate the biblical account, despite a relatively common misconception that Israel was a strictly monotheistic society. That was the idea—but that, they certainly were not.

Other such Baal-linked names have been revealed by archaeology. As yet, perhaps unsurprisingly, no such bosheth, “shame” names have yet been revealed. For now, this renaming convention is limited to the biblical text of Samuel. Nevertheless, it appears that during later periods, names including the baal element fell out of use—both in the Bible and as revealed by archaeology—likely due to the waning significance of this Canaanite storm god, Baal. Instead, we see a more widespread adoption of names incorporating the theophoric elements -yah or -el, as well as names inspired by other pagan deities of various nations.

We are left with one more question. Why does the book of Samuel—which exclusively contains all the transformed bosheth names—render them as such, conveying “shame,” while other books (such as Judges and Chronicles) do not?

It is not hard, within the overall context, to imagine the answer. The genealogies of Chronicles—a book traditionally cited to the scribe Ezra—represent dry, simple, factual family-tree accounting, and were recorded many centuries after the life of the individuals at hand. The book of Samuel, on the other hand—a book traditionally attributed in part to Samuel, and following his death, to the prophets Gad and Nathan—reflects a more dynamic, contemporary accounting of events at the time.

Actually, more specifically, all of the bosheth/besheth names are contained within the second book of Samuel—following the death of the Prophet Samuel. Samuel is actually quoted in the first book referring to one of these individuals with the original baal name element (1 Samuel 12:11). However, in the second book of Samuel, Joab—certainly no “saint”—refers to the same individual with the besheth name element (2 Samuel 11:21). So the use of the bosheth/besheth terminology was certainly not a mark of personal “righteousness” or piety.

It is notable that all such changed bosheth names appear after Samuel’s death, and just as David’s time on the run is ending, as he begins to come to power—first in Judah and then over all Israel. The name changes therefore appear against the backdrop of a particularly intense political scene. The war of legitimacy between the Saulide dynasty and the emerging Davidic dynasty was ongoing at the time—a “war” that, on some level, appears to be witnessed even in the use of names. Again, with David’s commander Joab (interestingly bearing a Yahwist name, meaning “Yahweh is my Father”) quoted using the besheth terminology (2 Samuel 11:21). And the assassins of Saul’s son and successor Ishbaal are also directly quoted using this same bosheth terminology (2 Samuel 4:8; again, themselves not “righteous” individuals—it’s worth noting that David did not condone this assassination and put these murderers to death).

Given that the bosheth names are only found in the context of David’s ascension to the throne and during his reign (2 Samuel), and given that this naming practice was not instigated by the “righteous” Prophet Samuel or scribe Ezra (both of whom used the original baal names)—yet these bosheth names were used by individuals decidedly loyal to David (however “unrighteous” certain of them were): Was this practice of renaming instigated by the court of King David, perhaps even at the behest of the king himself?

In sum, in the dynamic language of this period, in the very names used for these opposing sides, we see a sort of struggle played out—not just between David and Saul, but in a sense linguistically, between God and Baal—between righteousness and shame.