The Birth and Death of Biblical Minimalism

The long-running scholarly conversation surrounding the dating of biblical sites and artifacts can quickly become technical and tedious. This subject, however, is essential to the practice of biblical archaeology and, ultimately, the credibility of the Hebrew Bible as an archaeological tool.

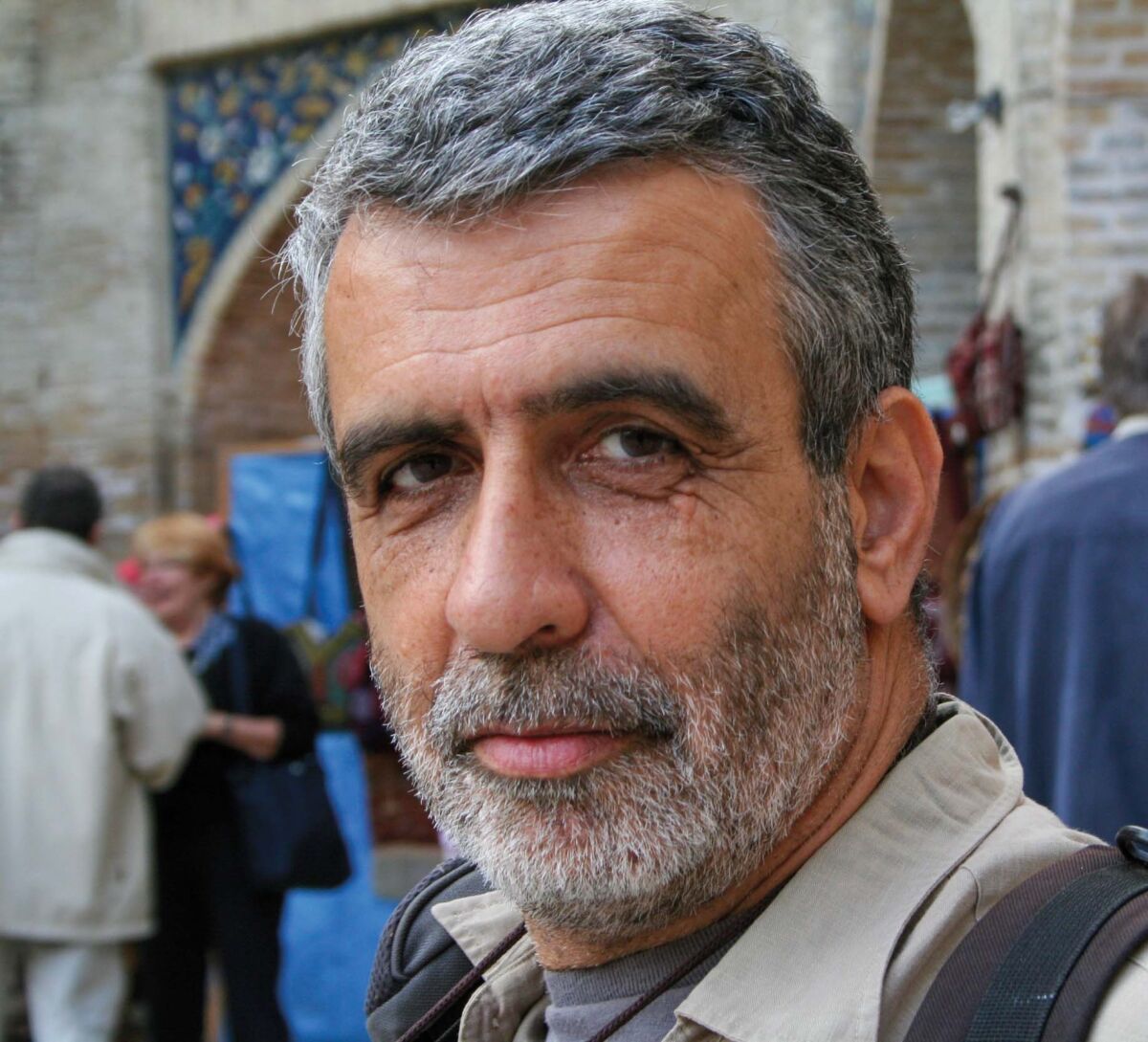

The following article, written by Hebrew University archaeologist Prof. Yosef Garfinkel, explores the topic of biblical minimalism. While the science sustaining Professor Garfinkel’s view here is both robust and compelling, it’s the style of writing—the clarity and vigor, the easy-to-follow logic—that makes it, in our opinion, one of the best elucidations of this subject.

This article originally appeared in the May-June 2011 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review (bar) and is republished here with permission from the Biblical Archaeology Society and Prof. Yosef Garfinkel.

“Biblical minimalism” as it is known, has gone through a number of permutations in the recent past. Its modern career began about 30 years ago, when bar was still a youngster. Since then it has been part of the ongoing debate regarding the extent to which historical data are embedded in the Hebrew Bible.

In the mid-1980s the principal argument involved the dating of the final writing of the text of the Hebrew Bible. The minimalist school claimed then that it had been written only in the Hellenistic period, nearly 700 years after the time of David and Solomon, and that the biblical descriptions were therefore purely literary.

The main developers of this position were centered at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark (Niels Peter Lemche and expatriate-American Thomas Thompson) and in England (Philip Davies and Keith Whitelam). The titles of their books tell us what they were about: a search for the real Israel of the biblical period (if indeed there was a real Israel). Thus Lemche (1988): Ancient Israel: A New History of Israelite Society; Thompson (1992): Early History of the Israelite People; Davies (1992): In Search of ‘Ancient Israel’; and Whitelam (1997): The Invention of Ancient Israel.

Much of the discussion focused on the biblical narrative about the 10th century b.c.e., the time of David and Solomon, the period known as the United Monarchy. Was there a United Monarchy? Were David and Solomon kings of a real state? Indeed, did they actually exist? Or were they simply literary creations of the biblical writers? For the minimalists, King David was “about as historical as King Arthur.”* The name David had never been found in an ancient inscription.

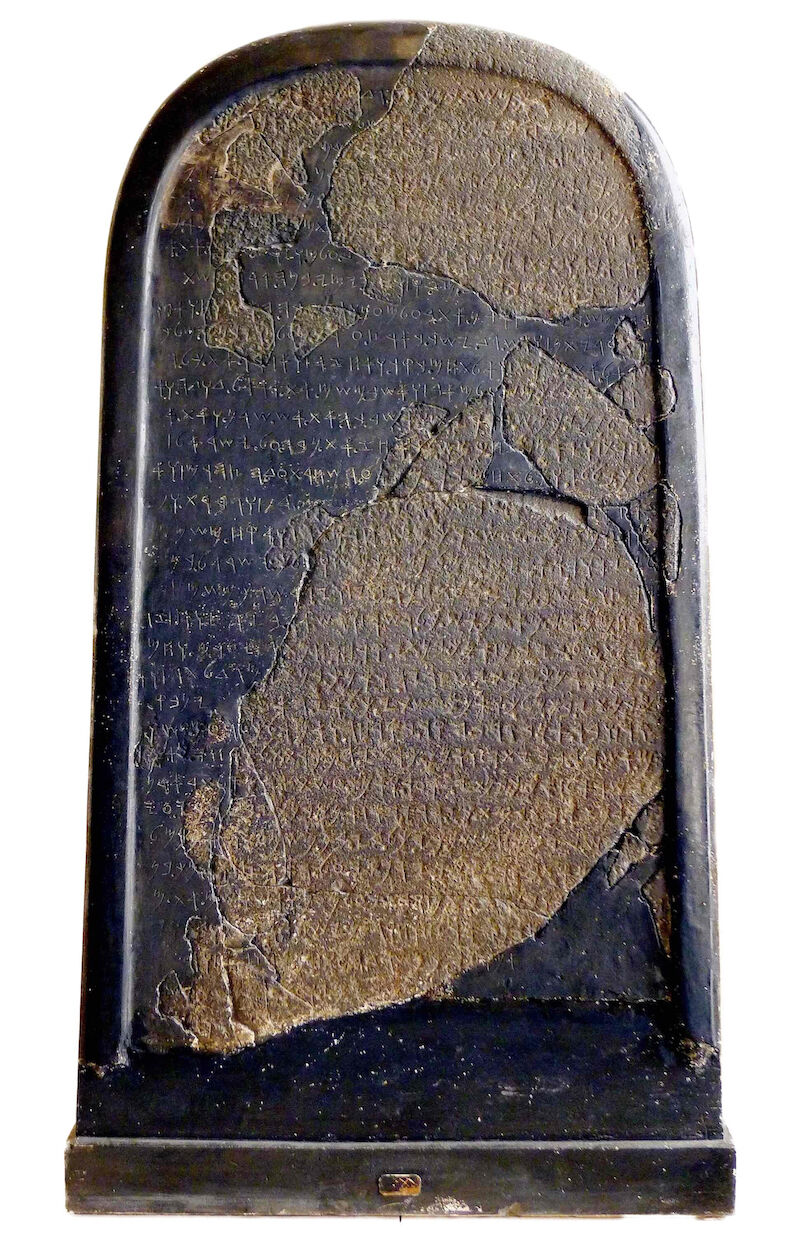

Hardly had the minimalist argument been developed than it was profoundly undermined by an archaeological discovery. In 1993 and 1994, several fragments of an Aramaic stela were found at the long-running excavation of Tel Dan led by Avraham Biran of Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem. The historical references in the inscription and the paleography of the writing make it clear that it dates to the ninth century b.c.e. Moreover, the text specifically mentions a king of Israel and a king of the “House of David” (Hebrew, bytdwd), that is, a king of the dynasty of David.

This discovery led to a reexamination of the well-known Mesha stela, a contemporaneous Moabite inscription discovered more than a century ago. André Lemaire, a senior paleographer at the Sorbonne identified in that text an additional reference to the House of David.** This was subsequently confirmed by another senior paleographer, Émile Puech of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française in Jerusalem.1

Thus, there is at least one, and possibly two, clear references to the dynasty of David in the ninth century b.c.e., only 100–120 years after his reign. This is clear evidence that David was indeed a historical figure and the founding father of a dynasty.

This led to the collapse of the minimalist paradigm. There was a David. He was a king. And he founded a dynasty. The minimalists reacted in panic, leading to a number of suggestions that now seem ridiculous: The Hebrew bytdwd should be read not as the House of David, but as a place named betdwd, in parallel to the well-known place-name Ashdod.2 Other minimalist suggestions included “House of Uncle,” “House of Kettle” and “House of Beloved.”†

Nowadays, arguments like these can be classified as displaying “paradigm-collapse trauma,” that is, literary compilations of groundless arguments, masquerading as scientific writing through footnotes, references and publication in professional journals. The Tel Dan stela ended the first phase of the debate regarding the historicity of the Hebrew Bible, demonstrating that the mythological paradigm was nothing but a modern myth.

After the collapse of this mythological paradigm, a new strategy was developed by the minimalists. The central method was to lower the dating of the archaeological material that had previously been attributed to the time of David and Solomon by nearly a hundred years—from the early to mid-10th century b.c.e. to the late tenth or even ninth century b.c.e. It was an argument based strictly on archaeology. The leading developer and proponent of this argument is Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University. It rests on the so-called “Low Chronology,” as opposed to the traditional chronology.

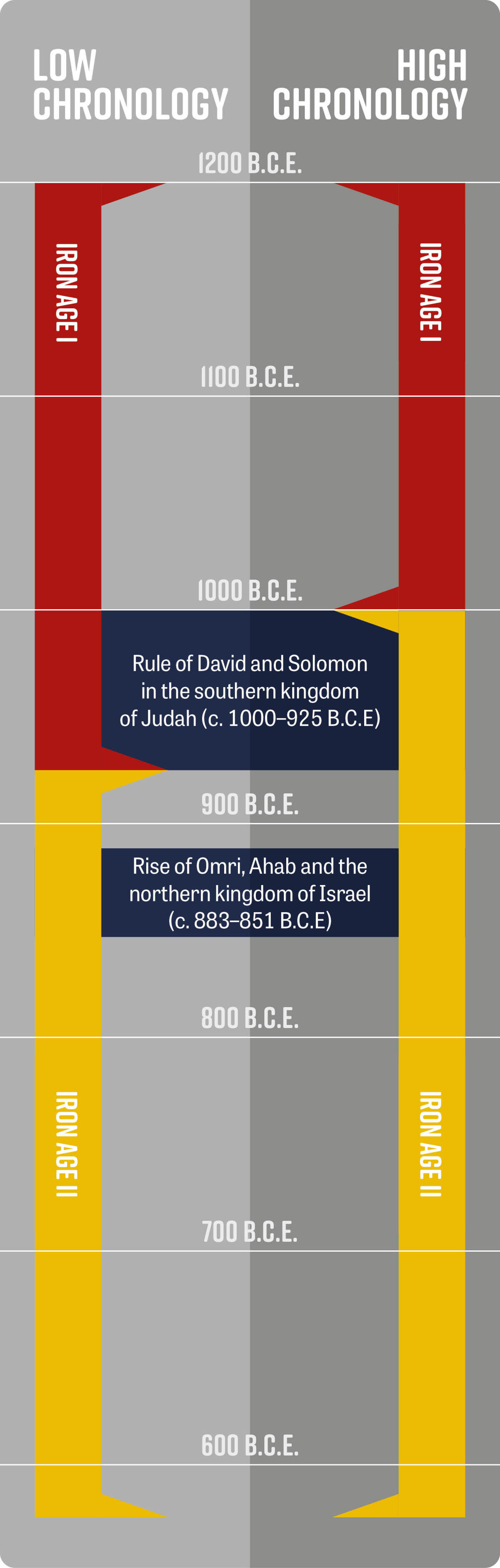

Here is how it works: The archaeological period that archaeologists call Iron Age i in Judah and Israel was a period of agrarian communities organized in a tribal social organization (described in the biblical tradition as the period of the judges).

The next period, Iron Age ii, was a period of urban society and centralized state organization (described in the biblical tradition as the period of the kings). On this there is general, one might almost say universal, agreement. Likewise it is agreed that David and Solomon ruled from about 1000 to about 930 b.c.e. The question is whether this roughly 75 years was in Iron Age i or Iron Age ii (or, more specifically, Iron Age iia). That is, during David and Solomon’s time, were Judah and Israel characterized by agrarian communities (Iron Age i) or by urban society and a centralized state organization (Iron Age iia)?

According to the traditional (or high) chronology, the transition from Iron Age i (agrarian communities) to Iron Age ii (urban, centralized states) occurred in about 1000 b.c.e. This places David and Solomon in Iron Age ii, ruling a central, organized, urban state. By lowering the date of the transition from Iron Age i to Iron Age ii, the minimalists succeeded in placing David and Solomon in Iron Age i. All the magnificent archaeological materials, including monumental architecture, that had been previously dated to the time of David and Solomon were now dated later. And the poor materials that were previously assigned to the pre-state period of the judges (in biblical terms) now became evidence of life in the time of David and Solomon.

Finkelstein’s Low Chronology lowered the date of the transition from Iron Age i to Iron Age ii to about 925 b.c.e. A more extreme approach lowered the transition to as late as c. 900 b.c.e. (the “Ultra-Low Chronology”).3

According to the Low Chronology, urbanization in Israel and Judah occurred only at the end of the 10th century b.c.e., and David and Solomon were not rulers of a kingdom but rather local tribal leaders.

The proponents of the Low Chronology place their primary reliance on radiocarbon (also called C-14 or carbon-14) dating of organic remains, such as wood and olive pits, found in archaeological excavations. During the last decade, hundreds of organic samples from Iron Age sites were sent to labs for radiometric dating in order to verify or contradict the Low Chronology. Despite the scientific halo that may appear to indicate precision, the dates provided by radiocarbon analysis are often quite iffy.* (for more on this, click here). The organic material being tested may be long-lasting like wood or short-lived like olive pits. The precise archaeological stratum the specimen came from (indicating the archaeological period—Iron Age i, say, or Iron Age ii) may be uncertain. The archaeological stratum of the sample may be narrow, lasting only a few years, or broad, lasting a century or more. Moreover, all agree that the resulting date must be adjusted, or “calibrated,” to arrive at a more dependable date. There are several different ways of doing this.

Finally, the result gives us only a probability that the material was created at the date given by the carbon-14 analysis; the greater the range of dates, the higher the probability that the true age of the specimen falls within that range. Because of all these uncertainties, many samples must be tested in order to have confidence in the results.

In the early days of attempting to support or refute the Low Chronology, various problems in carbon-14 dating were exposed and corrected, and the advocates of the Low Chronology declared without hesitation that the dating results of hundreds of samples clearly supported the Low Chronology.4 Conversely, the same dates were also presented as supporting the traditional high chronology.5 It is indeed quite bizarre to see the same corpus of radiometric dates used to support both chronologies.

More recently, more reliable radiocarbon samples were tested from Megiddo (Stratum K-4), Yokneam (Stratum xvii) and Tell Keisan (Stratum 9a), all in the Jezreel Valley and Acco plain, that is, all in the northern kingdom of Israel. These layers represent the last Iron Age i settlement in each site. All of these strata were followed by destruction layers, which make dating more reliable. The results were written up by 2007, although not published until 2009, by Finkelstein and his colleague Eli Piasetzky.6 The results show an uncalibrated, weighted average destruction date of 2852 plus or minus 13 years b.p. (before present). After calibration, the date is around 1000 b.c.e. This is exactly the dating indicated by the traditional high chronology decades ago. Thus, Finkelstein is not only the founding father of the Low Chronology but also its undertaker.

This is not the end of the story, however. It is true that radiocarbon dates from other sites in the northern kingdom of Israel do support the view that archaeological material from Iron Age iia can be dated to the end of the 10th century b.c.e. This of course pleased the minimalists. But these radiocarbon dates from sites in the northern kingdom of Israel did not answer the question with regard to Judah (where David came from).

The argument that Judah was an agrarian society until the end of 10th century b.c.e. and that David and Solomon could not have ruled over a centralized, institutionalized kingdom before then has now been blown to smithereens by our excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa, where we have been in the field for the past four summers.

bar readers have already had two reports on this exciting excavation.* Qeiyafa is a heavily fortified site in Judah on the Israelite/Philistine border. It clearly reflects a highly organized society. Moreover, it is essentially a one-period site (except for a small occupation in the Hellenistic period and a Byzantine fortress at the top of the site). And this period is clearly Iron Age iia. The short Iron Age iia habitation ended with the destruction of the site. Should this settlement at Qeiyafa be dated to some time in the early 10th century b.c.e., when David and Solomon ruled, or to the end of the 10th century, when later kings ruled separately in Judah and in Israel?

Radiocarbon analysis of short-lived olive pits demonstrated that this heavily fortified site could not date later than 969 b.c.e. (with 77.8 percent probability). This date fits the period associated with King David (c. 1000–965 b.c.e.) and is too early for King Solomon (c. 965–930 b.c.e.). The fortified city of Qeiyafa indicates that Iron Age iia began in Judah at the very end of the 11th century b.c.e., thus rendering the Low Chronology paradigm nothing but a modern myth.

If you think that is the end of the minimalist argument, you would be mistaken. What if Qeiyafa, lying on the Israelite/Philistine border is Philistine rather than Israelite (that is, Judahite)?

Thus began a new phase in the evolution of the minimalist approach. The basic minimalist argument now to be considered is very simple: Even if David was a historical figure (given the Tel Dan stela), and even if the transition from Iron Age i to Iron Age ii began at the end of the 11th century b.c.e. in Judah (given the dating of Khirbet Qeiyafa), there was still no kingdom in Judah in the 10th century b.c.e. because Qeiyafa (on the Judahite/Philistine border) is a Philistine site, part of the kingdom of Gath, identified as Tell es-Safi, less than 10 miles west of Qeiyafa.7

To us, it is clear that Qeiyafa is not a Philistine site for the following reasons:

1) No pig or dog bones were found at Qeiyafa, while at Gath (Tell es-Safi) pigs and dogs were part of the diet, as indicated by the bone remains found there.*8

2) The main entrance to Qeiyafa faced Jerusalem rather than Philistia.

3) Qeiyafa is encircled by a double, or casemate, wall. City walls like this are unknown in Philistia, but are common in Judah.

4) In Philistia only five major cities—those mentioned in the Bible: Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gaza, Gath and Ekron—were fortified. No field settlement in Philistia is known to have been fortified. This is not so in Judah, consistent with the major fortification at Qeiyafa.

5) The now-famous ostracon from Qeiyafa is inscribed with “proto-Canaanite” letters in the Hebrew language, according to our epigrapher, Haggai Misgav. In the recently published inscription from Philistine Gath, the names are Indo-European. The script of the Gath inscription is also “proto-Canaanite,” but the language is probably Philistine.

I suppose if we were ever able to convince the doubters that Qeiyafa is not a Philistine site and not in Philistia, we would then have to prove that it is not at least seven other autochthonic nations mentioned in the Bible: Hittites, Girgashites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites (Deuteronomy 7:1).

To the extent that radiometric readings do reflect a late-10th-century b.c.e. date for the transition to Iron Age iia, they come exclusively from sites in the northern kingdom of Israel. The Iron Age iia samples were taken from places like Megiddo, Tel Rehov, Tel Dor and Hazor, but not from sites in the south like Arad, Beersheba, Lachish or the earlier strata of Tel Beth-Shemesh. Moreover, even in their northern sites, the proponents of the Low Chronology rely on Iron Age iia samples not from the beginning of this period but only from a later iia stratum (as at Megiddo). It is a clear methodological error to assume the date of the beginning of a period by dating its later stages.

Paradoxically, the radiometric results relied on by the advocates of the Low Chronology in fact support the chronological sequence described in the biblical narrative. The Bible clearly states that the earliest Israelite kingdom was established in Jerusalem (in the early 10th century b.c.e.) and that the northern kingdom of Israel was created only some 80 years later. The northern Israelite capital of Samaria was not built until about 120 years after Jerusalem had been established as the capital. Some modern scholars try to reverse the sequence indicated in the Bible. They claim that because the biblical narrative was edited and perhaps written hundreds of years later, it cannot be taken as historical evidence. Therefore, they argue, our historical understanding must be based on inscriptions from Mesopotamia and Egypt. Outside the Bible, the kingdom of Israel is first mentioned in Assyrian royal inscriptions and in the Mesha stela in the middle of the ninth century b.c.e. Only much later is the kingdom of Judah mentioned—by the Assyrian monarch Sennacherib at the end of the eighth century b.c.e. Based on this sequence, a new paradigm was created by some minimalists, according to which, contrary to the biblical account, the northern kingdom of Israel was developed first, while the kingdom of Judah arose only two centuries later.

At first, the Low Chronology seemed to support this new paradigm, as it dates Iron Age iia sites mainly to the late 10th and early ninth centuries b.c.e. Geographically, however, since these dates come only from sites in the northern kingdom of Israel, all they indicate is that building activities in the kingdom of Israel began mainly in the ninth century b.c.e. This is exactly when the biblical tradition indicates that a kingdom was established in this region!

The fallacy in the reasoning of the Low Chronology supporters is to apply these dating results to the kingdom of Judah and argue that urbanism in Judah also started only in the ninth century b.c.e.

Each of these kingdoms must be dated independently. Independent dating suggests that the kingdom of Judah rose in approximately 1000 b.c.e., as indicated by the radiometric results from Qeiyafa. The northern kingdom of Israel, on the other hand, developed around 900 b.c.e., as indicated by the radiometric dates obtained from that region.

The biblical tradition and the radiometric dating actually support each other. Placing the formation and development of the kingdom of Israel earlier than the kingdom of Judah, as the proponents of the Low Chronology have done, is simply another modern myth.9

Some rather mundane finds in our Qeiyafa excavation powerfully buttress the conclusion that an urbanized state and early administration existed in Judah in the early 10th century b.c.e. More than 20 standardized storage jars, each standing about 2 feet high, were excavated near the city gate. The jars are tall and narrow with short necks, rounded shoulders and relatively small, flat bases. On the handle of most of these vessels was the impression of one or two fingers. These pottery containers were probably used for the collection of taxes, in the form of olive oil, wine and other agricultural products. We decided to do a petrographic analysis of the clay, which revealed that they were all manufactured at an as-yet-undiscovered production center near Qeiyafa. These standardized jars from 10th-century Qeiyafa were apparently an early development of the common eighth-century b.c.e. jar handles stamped l’melekh (“belonging to the king”). Both the l’melekh handles and our Qeiyafa handles impressed with fingerprints reflect a centrally organized society imposing governmental regulation—in short, a state.

Powerfully buttressing this conclusion is the Hebrew ostracon, indicating the existence at this time of a literate society with scribes, even in this settlement far from the state capital at Jerusalem.* Moreover, this inscription is not simply evidence of a commercial transaction, but of a literary composition. Although we can barely recover the text, it seems clear that it relates to ethics and justice. The Qeiyafa excavation indicates that in the early 10th century b.c.e., the time of David, there was already a fortified city at a strategic border location of Judah. This city already reflects a clear urban concept that integrates the casemate city wall with the nearby houses. Four other cities with this urban planning are known from Judah, although from a slightly later time: Tel Beth-Shemesh, Tell Beit Mirsim, Tell en-Nasbeh and Beersheba.

The Qeiyafa excavation shows that this urban concept had already been developed in the time of King David. The reader will notice that I have not used the term “United Kingdom,” the common nomenclature for the kingdom of David and Solomon that is supposed to have included both the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah (which, for the first seven years, David ruled from Hebron prior to conquering Jerusalem—2 Samuel 5:5). Whether there was indeed a United Kingdom, with one dynasty ruling from Jerusalem over both Judah and Israel, cannot be answered by the Qeiyafa excavations. To date, no fortified urban centers from the early 10th century b.c.e. have been found in the area of the northern kingdom of Israel. Therefore I have avoided the term United Kingdom. What is clear, however, is that the kingdom of Judah existed already as a centrally organized state in the 10th century b.c.e.

Footnotes

*Philip R. Davies, “‘House of David’ Built on Sand,” BAR, July-August 1994.

**André Lemaire, “‘House of David’ Restored in Moabite Inscription,” BAR, May-June 1994.

†See David Noel Freedman and Jeffrey C. Geoghegan, “‘House of David’ Is There,” BAR, March-April 1995; Anson F. Rainey, “The ‘House of David’ and the House of the Deconstructionists,” BAR, November-December 1994.

*See Lily Singer-Avitz, Archaeological Views: “Carbon 14—The Solution to Dating David and Solomon?” BAR, May-June 2009.

*Hershel Shanks, “Newly Discovered: A Fortified City From King David’s Time,” BAR, January-February 2009; “Prize Find: Oldest Hebrew Inscription Discovered in Israelite Fort on Philistine Border,” BAR, March-April 2010.

*See Avraham Faust, “How Did Israel Become a People?” BAR, November-December 2009.

*See “Prize Find: Oldest Hebrew Inscription Discovered,” BAR, March-April 2010.

Endnotes

1 Émile Puech, “La stele araméenne de Dan: Bar Hadad II et la coalition des Omrides et de la maison de David,” Revue Biblique 101 (1994), p. 215. See also Anson F. Rainey, “The ‘House of David’ and the House of the Deconstructionists,” BAR, November-December 1994.

2 Niels P. Lemche and Thomas L. Thompson, “Did Biran Kill David? The Bible in the Light of Archaeology,” Journal of the Study of the Old Testament 19 (1994), pp. 3–21.

3 Ayelet Gilboa and Ilan Sharon, “An Archaeological Contribution to the Early Iron Age Chronological Debate: Alternative Chronologies for Phoenicia and Their Effects on the Levant, Cyprus and Greece,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 332 (2003), pp. 7–80; Ilan Sharon, Ayelet Gilboa, Timothy Jull and Elisabetta Boaretto, “Report on the First Stage of the Iron Age Dating Project in Israel: Supporting the Low Chronology,” Radiocarbon 49 (2007), pp. 1–46.

4 Sharon et al., “Report on the First Stage of the Iron Age Dating Project in Israel.”

5 Amihai Mazar and Bronk Ramsey, “14C Dates and the Iron Age Chronology of Israel: A Response,” Radiocarbon 50 (2008), pp. 159–180.

6 Israel Finkelstein and Eli Piasetzky, “14C and the Iron Age Chronology Debate: Rehov, Khirbet en-Nahas, Dan and Megiddo,” Radiocarbon 48 (2006), pp. 373–386.

7 See also Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor, Khirbet Qeiyafa, Vol 1: Excavation Report 2007–2008 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2009).

8 Nadav Na’aman, “In Search of the Ancient Name of Khirbet Qeiyafa,” Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 8 (2008).

9 Aren Maeir, personal communication.

10 For additional discussion, see Amihai Mazar, “The Spade and the Text: The Interaction Between Archaeology and Israelite History Relating to the Tenth–Ninth Centuries B.C.E.,” Understanding the History of Ancient Israel (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2007), pp. 143–171.