Think You Know Your Biblical Figures? The Hebrew Pronunciation of Their Names Might Surprise You

Many of our readers are familiar with the stories and figures in the Bible. Solomon and his wisdom. Samson and his strength. Moses before the Pharaoh. Eve’s son Abel, the first murder victim. Rebekah and her romance with Isaac.

English readers, that is—because these names are actually very different in Hebrew. In fact, many of our beloved biblical names are very different in the Hebrew tongue. Have you heard of the wisdom of Shlomo? The strength of Shimshon? Moshe before the Paro? The murder of Chavah’s son Hevel? The romancing of Rivkah and Yitschak?

In this rather more lighthearted article, we’ll take a look at the typical Hebrew pronunciation of names that, over the centuries, have become rather mongrelised into our English language, being distorted and lumped into our peculiar English adoptive blend of Teutonic and Romance languages (among others). As was rather aptly put by James D. Nicoll: “[O]n occasion, English has pursued other languages down alleyways to beat them unconscious and rifle their pockets for new vocabulary.” (It seems that many biblical names were harmed in this process!) The weird, unnatural complexity of the English language is brilliantly explained in this short video.

Hebrew, though, has its own complexities—and as such, many of the famous biblical names are quite different from what English speakers are familiar with. We’ll examine them here according to our letters of the English alphabet. (A note to particularly fastidious readers and enthusiasts: The following is a general, simplified comparison of names as they are typically transcribed and pronounced in English, with the way they have been conveyed through the biblical Hebrew Masoretic text and on into standard modern Hebrew pronunciation. The below makes no pretence of delving into complex, ancient etymologies!)

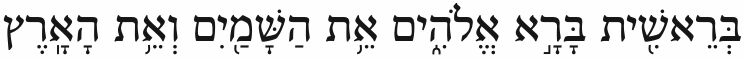

First of all: Note that Hebrew is a consonantal language. In ancient (and most modern) Hebrew text, vowels were not written. When they were—such as in the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible, as a pronunciation aid—they were inserted through a system of dots and dashes in and around the letters, known as “nikudot/niqudot.” Certain “nikudot” are pronounced differently by different groups—we will here go with the standard pronunciations in modern Hebrew. As such, besides differentiating consonants (as we will see below), you’ll find from the get-go that many of the vowels in our English-ified Hebrew names will be very different.

With that, let’s start with our first letter of the English alphabet.

- A. We English speakers love to chew on our long vowels. Hebrew vowels are much shorter: The vowel “a” is pronounced with a short “ah” sound (never “AY”). Thus, names such as David—which we would pronounce as a long DAY-vid—would actually be pronounced DAH-vid. (And while we’re on the topic, emphasis is often placed on the last syllable of Hebrew words—thus, Dah-VID.) Agag (which is often pronounced AY-gag) is Ah-gag. Amos (AY-mos) is Ah-mos. Satan (SAY-tan) is Sah-tahn. What if there are two “a”s (like Baal—often pronounced BAY-al)? That’s no excuse; just reemphasize the same sound (Bah-ahl). As for a couple of names of note starting with “A” that are relatively different from their English versions, take Aaron as an example. (Have you ever wondered why this one is spelled with two A’s? Ironically, we give this name a short “a” vowel sound!) In Hebrew, it is actually AHA-ron (similar to the pronounciation of its possible ancient-Egyptian equivalent). Another such name is Abel—this name is actually Hevel (note the above-mentioned differentiation in vowels—and for the “b” bit, see below). And Canaan? Ironically, we give emphasis to the initial A (as in, KAY-nan) when actually, that vowel is not there. It is more akin to Kn-ah-ahn.

- B. This one may throw you. This Hebrew letter can be either pronounced as a “B” or as a “V.” If it’s at the beginning of a word, you’re typically OK—Benjamin, Ben-Hadad, Bildad. If it’s within a name, however, it often changes to “v”. Thus, Babel becomes BaVel, Abraham becomes AVraham, Abigail becomes AVigail, Obadiah becomes OVadiah, Tubal-cain becomes TuVal-cain, Rebekah becomes RiVkah, Caleb becomes CaleV, Deborah becomes DVorah, Moab becomes MoaV, and Mount Ebal becomes Mount EVal.

- C. Various names in English starting with “C” may be pronounced with a hard “k” sound or “s” sound. For transliterated biblical names, the latter is never the case. Caesarea, for example, is pronounced KAE-sah-rea. And as for names starting with “Ch”—there is no “ch” sound (i.e. the sound we make for the word CHips) in the Hebrew language. (One of the existing Hebrew letters is modified with an apostrophe, in order to reflect this sound when transliterating into Hebrew from modern English.) Biblical names with “ch” typically represent a guttural Hebrew letter that, in turn, we do not have in English—a letter properly pronounced similarly to the ch in “loch” (sometimes represented as Kh or Ḥ. One individual aptly described the pronunciation of this sound as “hocking a loogie.”) See also H.

- D. No problems here.

- E. Again, no major problems here. There can be longer “ee” sounds, but oftentimes, as with “A,” this letter is typically on a much shorter rope than we would normally give it (try “eh”). For example, our stretched out Eli (EE-lie) should almost be reversed: Eh-lee (akin to our English name Ellie). One famously poorly translated name starting with E is Eve—it’s actually Chavah/Chawah (starting with the above-mentioned guttural “Ch/Kh/Ḥ” sound). Another is Enoch—think Chanoch. (It appears we can thank the Greeks for our dropping of this initial letter.)

- F. See P.

- G. This one’s typically fine—but beware, it’s always the “gh” sound, never “j.” Agee may, for example, be pronounced Ay-jee in English, but it’s actually Ah-ghe. Also, certain words starting with G in English make no such sound in modern Hebrew. For example, Gomorrah is actually pronounced Amorah, Gaza is Aza. The initial Hebrew letter in these names is one that nowadays is simply a “silent” letter, a glottal-stop—though anciently, it apparently had more of a discernable guttural sound, perhaps more akin to the equivalent Arabic letter, or even akin to our letters G or K. For example, transliterated Assyrian inscriptions refer to King Omri (whose name begins with this same letter) as Gumri or Kumri. The name of the Elamite king who battled Abraham, Chedorlaomer (including the same Hebrew letter), represents the Elamite Kudur-LaGomer. As such, here, perhaps the English (for Gomorrah and Gaza) is closer to the original sound than modern Hebrew is!

- H. This one can be a little difficult. Names starting with H can either reflect the equivalent, soft Hebrew letter, such as Hadad or Heman (you can’t get a more masculine name than that!), which is fine; or, they can reflect the hard “Ch/Kh/Ḥ” guttural sound. Examples of this include: Habakkuk, which is CHavakuk; Haggai, which is CHagai; Hezekiah, better pronounced CHezkiah; Nehemiah as NeCHemiah; and Noah as NoaCH. Some names in this bracket completely omit the transliteration of this letter: For example, Ezekiel is (hold onto your seat) YeCHezkel. And some add an “H” where none is—for example, Hebrew is actually Evri/Ivri.

- I. As with “A,” be careful of overdoing it. It represents the sounds “ih” or “ee”—never the common English sound “eye.” For example, Ira—rather than being pronounced EYE-ra—is E-ra. Malachi (which we often pronounced “Malak-EYE”) is pronounced Malachee. Oftentimes, when at the start of a name, it may also represent the Hebrew letter more akin to Y. Isaac, for example, rather than being pronounced EYE-zak, is pronounced (brace yourself) YItschak. Israel? YIssrael. Issachar is YI-saschar. Isaiah (which, again, we pronounce as EYE-zaiah) is Yeshiah.

- J. Ah, the infamous J. This is perhaps the most egregious of them all. There is no “J” (sometimes represented in pronunciation as “dʒeɪ”) sound in the Hebrew language. The better equivalent is “Y” (which sound the original German letter J was intended to express—the English use of the “J” sound warrants a separate article in itself). Think Hallelujah, one that we do actually pronounce right—HalleluYah. Thus, Jehovah is properly YEhovah (or its alternate forms, such as Yahweh/Yahveh—there is much debate as to the exact translation of this name). Jacob is Ya’akov. Jesse is Yeshai. Joshua is Yehoshea. Jeremiah is Yeremiah. Joel is Yoel. Jeroboam is Yerovam. Jerusalem is Yerushalayim. Kirjath-Jearim is Kiryat-Yearim. Jew is Yehudi (from Judah—Yehuda). Ijon—which is sometimes pronounced rather brutally as EYE-Jon—is simply Ee-Yon. And perhaps most famously, the name Jesus in Hebrew is actually Yeshua (a related form of the name “Joshua”).

- K. This letter isn’t too problematic. Note that on rare occasion, it may represent the “Ch/Kh” guttural sound.

- L. No real issues here. But when it comes to the name of Boaz’s father, Salmon, it’s not the same as the fish: The “L” is pronounced! (Though there’s a story to this name, too …. Every time it is mentioned in the Bible, it is spelled a different way! See our article on this peculiar individual here.)

- M, N. No real difficulties here.

- O. This letter can be a strange one. The Hebrew letter sometimes transliterated as “O” can also be a “u,” “w” or even “v” sound. It’s why the biblical name for Greece, Javan (pronounced Yavan), is directly related to the name of one of the Greek progenitor/demi-gods, Ion. It’s also part of the reason that ChaWah/ChaVah has become our English EVe. It’s why the words for David (Hebrew dvd), uncle (Hebrew dod) and pot/kettle/water heater (Hebrew dud/dood) are all spelled with exactly the same letters, but pronounced differently based on the added vowel “nikudot.” And here’s a fun fact relating to a name starting with this letter, relating to the difficulty certain English speakers sometimes have with some biblical names: The famous television personality Oprah Winfrey was actually named Orpah (or Arpah), an individual mentioned in the book of Ruth. Apparently people had so much trouble trying to figure out the name that Oprah became the adopted form!

- P. Redirected from “F.” This is because the same Hebrew letter for “P,” depending on the “nikudot,” can also represent the sound “f”. Certain names transliterated into English as “ph,” thus giving a “f” sound, are actually properly the Hebrew sound “p.” One example is Phineas/Phinehas, pronounced in English as Fineas: In Hebrew, this is actually PIN-chas (again, with the guttural “ch”). Pharaoh in Hebrew is PAro. Pharez is Perets (see Z for the latter part of this name). Ironically, in a case of roundabout-ery, PHilistines is the biblical PL-ishtim, while the modern PAlestinians is PH/FA-lastinim.

- Q. Simply an alternate of the English “k” sound (as is sometimes shown in the varying transliterations of the Arabic word Qur’an/Koran). Since there are two “k” letters in the Hebrew alphabet—from which our letters K and Q are actually derived—some choose to more accurately render words with the more directly represented letter (e.g. our above-mentioned “nikudot” vs. “niqudot”).

- R. The Hebrew “R,” properly pronounced, is a difficult one—it’s articulated from the back of the throat/tongue (similar to German and French, for example), rather than rolled at the front of the tongue (as with English and Spanish).

- S. There are two letters in the Hebrew alphabet that have an “s” sound. One of these letters, depending on the “nikudot,” can also represent the “sh” sound. The latter is the most common. As such, many of our familiar “S”-named biblical figures are actually pronounced with a “sh” sound. (In addition, the Greek language does not have a “sh” sound—hence why, in the ancient development toward our modern English language, many of these biblical “sh” names have taken on the sound “s”.) For example: Samson is Shimshon, Solomon is Shlomo, Samuel is Shmuel, Simeon (which we pronounce rather strangely as Si-Me-On) is simply Shimon, Hosea (which we pronounce HoZea) is HoSHea, Siloam is Shiloach, Samaria is Shomron, Assyria is Ashur, Manasseh is Menasheh, and even Sabbath is Shabat. Sometimes, the reverse is true, and an English-pronounced “sh” sound will actually be the Hebrew “s” (as with Issachar, sometimes pronounced in English something like Ishakar—this is the Hebrew Yisaschar). There is something else to beware of here: There is a Hebrew letter, sometimes transliterated into English as the letter S (but more often Z) which actually has a “ts” sound (see Z below). A final point: We English speakers oftentimes like to give our S’s a “z” sound. Thus, we might end up pronouncing names like Asa as AZA. It’s unfortunate: This name in English actually looks as it sounds in Hebrew! Perhaps a better transliteration to force the “s” sound would be Assa. Same with Israel (which we pronounce IZ-rael)—try Yiss-rael.

-

T. In modern Hebrew, there are two letters representing the sound “t”: ט and ת. (The original ancient form of the latter,

, is where the shape of our lowercase letter, “t,” comes from.) Oftentimes in English translations, the former letter will be represented as “t,” and the latter letter as “th” (unless it is starting a word). However, at least in modern Hebrew, there is no “th” sound. (It appears we can thank the Greeks for this: There are two different Greek letters that make a form of this sound!) Still, there is much variation in the interpretation of this letter. Certain Ashkenazi Jews, for example, pronounce it as “s” (again, depending on the “nikudot;” as such, for them, Sabbath becomes ShaboS). But the widespread modern Hebrew pronunciation of this letter is with a hard “t” sound. Thus, GoliaTH becomes GalyaT, RuTH becomes RooT, BaTHsheba becomes BaTsheva, SeTH becomes SheT, MeTHuselah becomes rather transformed as MeTushelach, all the Beth- locations (Beth-shemesh, Beth-lehem etc.) become Bet- locations (Bet-shemesh, Bet-lechem etc.), Kirjath- locations become Kiryat-, and Sabbath becomes Shabat. Hey, we randomly do this already with Esther anyway, pronouncing the name properly as Ester.

, is where the shape of our lowercase letter, “t,” comes from.) Oftentimes in English translations, the former letter will be represented as “t,” and the latter letter as “th” (unless it is starting a word). However, at least in modern Hebrew, there is no “th” sound. (It appears we can thank the Greeks for this: There are two different Greek letters that make a form of this sound!) Still, there is much variation in the interpretation of this letter. Certain Ashkenazi Jews, for example, pronounce it as “s” (again, depending on the “nikudot;” as such, for them, Sabbath becomes ShaboS). But the widespread modern Hebrew pronunciation of this letter is with a hard “t” sound. Thus, GoliaTH becomes GalyaT, RuTH becomes RooT, BaTHsheba becomes BaTsheva, SeTH becomes SheT, MeTHuselah becomes rather transformed as MeTushelach, all the Beth- locations (Beth-shemesh, Beth-lehem etc.) become Bet- locations (Bet-shemesh, Bet-lechem etc.), Kirjath- locations become Kiryat-, and Sabbath becomes Shabat. Hey, we randomly do this already with Esther anyway, pronouncing the name properly as Ester.

- U. No big issues here. See O: the Hebrew sound is often associated with a different vowel pointing of the same letter, and in the same manner, this can sometimes actually be a “v” sound. Thus, Ahaseurus is actually AchashVerosh. Araunah is actually AraVnah (though there’s a lot more to this name—an article on this is forthcoming). Esau (which we would pronounce EE-saw) is Eh-saV. And names starting with U are never pronounced with our classic English “yu” sound—for example, Uriah/Urijah (often pronounced in English “YU-riah”) is actually closer in Hebrew to OO-riah. Uzziah (often pronounced in English as “YU-ziah”) is OO-ziah.

- V. See B, O, U and W. This sound may be represented by one of two Hebrew letters, one of which can also represent an “oh” or “oo” vowel.

- W. See O, U and V. Perhaps the only names of note here containing this letter are: the much-transformed name JeW (relating to Judah)—this is YehUdi (from Yehuda); and also YahWeh—this is sometimes rendered YahVeh.

- X. When used within a name, “x” can represent the combined sounds of two Hebrew letters, “k” and “s” (as in Arphaxad, or Arphaksad), which is no problem. There are some really weird differences, though, where it may represent a guttural “ch” sound, combined with a “sh”. ArtaXerxes, for example, is ArtaCHSHasta.

- Y. Totally fine. More of these, please! (See J and I.)

- Z. The Hebrew letter for Z is pronounced the same as ours. However, there is another Hebrew letter that we do not have in our alphabet, that is sometimes transliterated in English as Z or S. It is a letter that makes a “ts” sound (the same sound we make for the word pizza—“pi-TSa”). Names in this category include Zadok, pronounced TSah-dok (where the pretty brutally pronounced word Sadducees, Sad-ju-sees, is derived from—it’s actually Tsadokim, or in other words, “Zadoks”). Zedekiah is Tsedkiah, Zion is Tsion, Melchizedek is Malki-tsedek, Zephaniah is Tsfaniah.

If the above has whet your appetite for more about the peculiarities of the Hebrew language, you haven’t seen anything yet: Check out our article “Remarkable Linguistic ‘Coincidences’ in the Hebrew Bible.”