A Sunken City of Mitanni Has Risen. Will It Shed Light on the Judges Period?

A team of German and Kurdish archaeologists revealed this week the fruits of a rare opportunity: the excavation of a previously sunken, 3,400-year-old town in a Mosul reservoir.

Researchers had already been aware of the existence of the Late Bronze Age site, named Kemune, but it was never properly researched before the creation of the water reservoir in Iraq’s Kurdistan region 40 years ago, which entirely flooded the ancient settlement. However, after a severe drought over the past year, the city reemerged from the depths, allowing archaeologists the chance for excavation and documentation. Through January and February, archaeologists from the University of Freiburg, the University of Tübingen and the Kurdistan Archaeology Organization (kao) were in a race against time to document the site, which has since been resubmerged. During this short two-month window, a number of exciting discoveries were made.

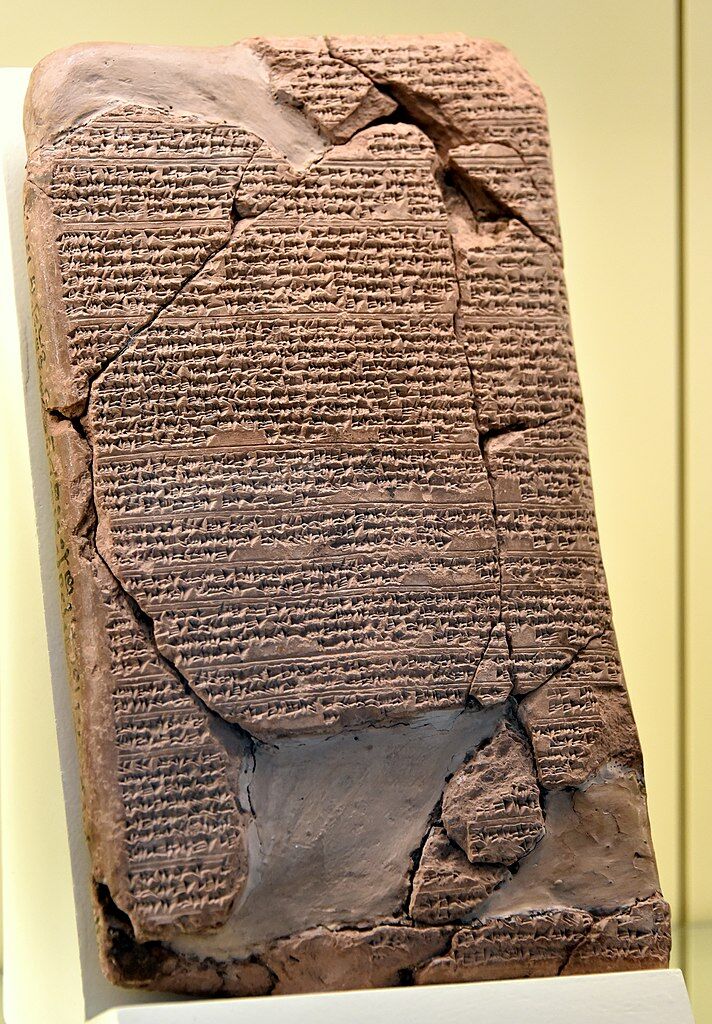

This town belonged to the enigmatic Bronze Age kingdom of Mitanni, and is postulated to be the city known in texts as “Zakhiku.” Situated along the banks of the Tigris River, the village was settled during the 200-year window of 1475–1275 b.c.e. This particularly rich archaeological site is believed to have been a trading hub. The archaeologists have uncovered a palace and numerous large structures, including towers, storage buildings and multistoried structures. Perhaps most exciting is the trove of more than 100 cuneiform inscriptions that has been found—many of them still sealed within their original clay “envelopes” (see the image below). University of Tübingen’s Dr. Peter Pfälzner noted that “it is close to a miracle that cuneiform tablets made of unfired clay survived so many decades underwater.” These inscriptions date to the Middle Assyrian period, apparently just following the collapse of the kingdom of Mitanni (circa 1350 b.c.e.). Experts are hoping that once translated, they will shed light on how the kingdom fell.

And for those with an interest in biblical archaeology, especially relating to the very early biblical periods, this kingdom—and its collapse—is of particular interest.

Judges 3:7-11 describe Israel’s very first oppression at the hands of a foreign power following their entrance into the Promised Land. “Therefore the anger of the Lord was kindled against Israel, and he gave them over into the hand of Chushan-rishathaim king of Aram-naharaim; and the children of Israel served Chushan-rishathaim eight years” (verse 8). The chapter proceeds to describe the rise of an Israelite leader named Othniel who fought against and defeated Chushan-rishathaim’s forces, freeing the Israelites.

The Hebrew-transliterated name “Aram-Naharaim” is an unusual one (sometimes translated as “Mesopotamia” in various English versions). Aram is a clear reference to the territory of Syria (which Mitanni controlled). But the title Naharaim is a direct match for the ancient Levantine title of the kingdom of Mitanni. Egyptian texts refer to it as Naharin. Canaanite texts—namely, the 14th-century b.c.e. Amarna Letters—name it Nahrima. Even the biblical name for the ruler of this polity is similar in form to names of the rulers of Mitanni—for a full explanation, see our article “Othniel v. Chushan-Rishathaim: Evidence for the Biblical Account.”

Besides this oppression account in the book of Judges, the kingdom of Mitanni—and particularly the date of its fall—is especially important in the world of biblical archaeology for another reason: the time frame of the Exodus.

There are two predominant “Exodus” theories. The first is that it occurred during the 1200s b.c.e., with the Israelite nation being established sometime during the latter part of that century; this is perhaps the more popularly cited theory among scholars, built upon the foundation of biblical minimalism (meaning that it contradicts various chronologies and events in the biblical account, for which it assumes errors). The other theory is a maximalist one that takes at face value the biblical chronological information (i.e. Judges 11:26; 1 Kings 6:1); in doing so, it places the Exodus in the 15th century b.c.e. and the start of the “judges” period in the first half of the 1300s b.c.e. You can read in detail about this two-way debate in our article here.

This is where the kingdom of Mitanni comes into play. The postulated late Exodus long postdates the fall of the Mitanni kingdom. An Israelite oppression at the hands of this polity could only be possible with an early Exodus time frame: within the 15th–14th centuries b.c.e. Furthermore, applying this early, literal biblical timeline not only allows for a general Mitanni oppression—it also aligns the very collapse of this polity during the same time frame as the collapse described in the Judges account.

So will we find out more about this empire’s collapse from the translation of these cuneiform tablets found at the Kemune excavation? We’ll have to wait and see. Whatever the case, the archaeological discoveries have already been exciting.

Meanwhile, take a look at our article “Othniel v. Chushan-Rishathaim: Evidence for the Biblical Account” to learn more about the remarkable parallels between Judges 3, the Mitanni oppression and the fall of the empire—including some surprising inscriptional evidence for King Chushan-Rishathaim and his nemesis, the judge Othniel.