Mesad Hashavyahu Ostracon: A Case of Biblical Law

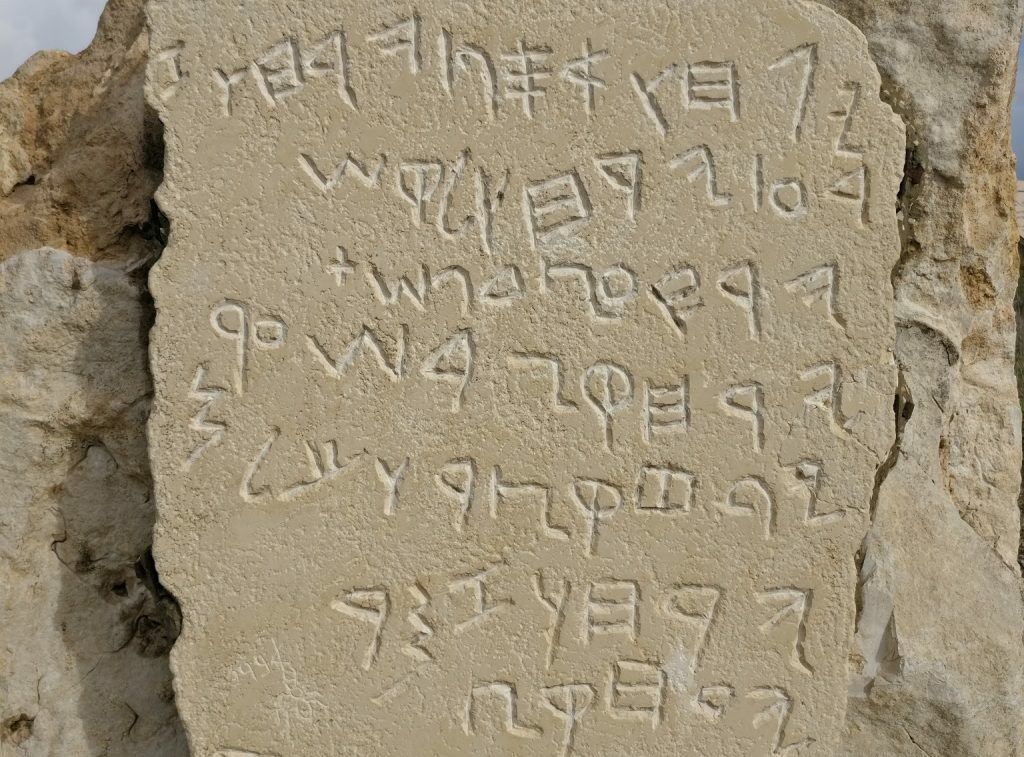

In 1960, while excavating a seventh century b.c.e. Judean fort on the southern Mediterranean coast between Jaffa and Ashdod, Israeli archaeologist Joseph Naveh discovered what would become an incredibly significant artifact for biblical archaeology: the Mesad Hashavyahu Ostracon. The 2,600-year-old pottery fragment found under a floor adjacent to the gatehouse complex is dated to circa 630 b.c.e., during the reign of King Josiah. The large piece is 20 centimeters tall and up to 17 centimeters wide.

The ostracon (inked pottery sherd) contains 14 lines of ancient Hebrew text. In the letter, a poor farmer presents his case, which he sees as unjust, to the governor at the nearby Mesad Hashavyahu fortress. (Naveh believed that the fine penmanship, in conjunction with the “awkward” language and repetition, seems to indicate that it was the farmer’s wording written down by a trained scribe.) The letter begins (translation by K. C. Hanson, adapted from W. F. Albright, 1969):

Let my lord, the governor, listen to the word of his servant. Your servant is a reaper. Your servant was in Hasar-’Asam, and your servant reaped, and finished, and stored [the grain] during the days prior to the Sabbath.

This text contains the first known extra-biblical reference to the Jewish Sabbath. This indicates that the Jews were continuing to observe the Sabbath “throughout their generations, for a perpetual covenant. It is a sign between Me and the children of Israel for ever” (Exodus 31:16-17). The farmer had to get all his work done because labor was forbidden on the Sabbath day, and any offender was to be put to death (verses 14-16). This respect for proper observance of the Sabbath fits well with the period to which the ostracon dates—again, that of righteous King Josiah.

Due to the context of the letter though, it is possible that this was no ordinary Sabbath. It may well have referred to the festival Shavuot (Pentecost), celebrating the conclusion of the spring harvest (Leviticus 23:9-22). Notice verses 15-16 (King James Version): “Even unto the morrow after the seventh sabbath shall ye number fifty days; and ye shall offer a new meat offering unto the Lord.” The “Sabbath” referred to in this farmer’s letter may well have been the conclusion of this 50-day spring (grain) harvest period.

Another archaeological discovery helps confirm this tradition. According to the Gezer Calendar (a 10th-century b.c.e. inscription), all reaping and measuring of grain was finished in the Hebrew month of Sivan (May-June, the time of Shavuot).

The letter continues:

When your servant had completed the reaping, and stored [the grain] during these days, Hoshavyahu ben-Shobi arrived, and he confiscated the garment of your servant when I had completed the reaping.

Here the poor farmer cites a biblical law found in Exodus 22:26-27 and Deuteronomy 24:10-15, detailing how to treat a hired servant—if his garment is taken as a lending pledge, it should be returned to him by sunset (so he is able to sleep in it). The mention of these biblical laws, even by a low-ranking farmer, suggests that they were well known and even enforced. Given the nature of the farmer’s petition, he was probably confident the governor would see to it that the biblical law was upheld and his garment was returned.

When King Josiah was young, he began a campaign of destroying pagan idols and restoring true worship. During later efforts to renovate the temple, a copy of the book of the law was found (2 Kings 22; 2 Chronicles 34). After hearing the words of the book, Josiah realized that his reforms hadn’t gone far enough and that his people were failing to keep forgotten, specific laws outlined in the Torah (perhaps including those alluded to in the Mesad Hashavyahu Ostracon). Understanding they were cursed for their disobedience, Josiah declared that the nation would once again hearken unto the words of the book and “do according unto all that which is written concerning us” (2 Kings 22:13). The effects of Josiah’s righteous rule resonated throughout Judea—hence even the poor farmer’s citation of biblical law and confidence in appealing to the governor to uphold it.

Hoshavyahu ben-Shobi was likely the local landowner or someone affiliated who took the farmer’s garment, perhaps as payment of debt. The letter continues:

It is already days since he took the garment of your servant. And all my brothers—who are reaping with me—can testify on my behalf.

Here again, in accordance with biblical law found in Deuteronomy 17:6 and 19:15, the poor farmer cited additional witnesses who could clear his name of any alleged wrongdoing. The letter finishes:

If I am innocent of any wrong, [give back] my garment; and if not, it is the governor’s right to [consider my case] and send word to him so that he restores the garment of your servant. And do not let [the plea of your servant] be displeasing to him.

Whether or not the complaint was ever processed or the farmer’s garment returned is obviously unknown. But the Hashavyahu Ostracon supplies a somewhat humorous yet in-depth view into biblical law as it was kept and upheld during the seventh century b.c.e.

Finds like these continue to add more credibility to the biblical account, as both a historical document (that really did have a very early original date of authorship) and an eternal binding law by which we are commanded to live.