Were the Celtic Druids Pagan Israelite Priests?

The Druids were a mysterious, ancient priestly class that operated in Western Europe, particularly in the British Isles. They came to some infamy following contact with the Romans, who brought reports of human sacrifice (thanks especially to the writings of Julius Caesar). Typically seen as barbarians, the Druids were in fact a highly regulated and educated pagan class that presided over matters not only religious but also judicial, medical and political. And today, after a 1,200-year hiatus, there has been somewhat of a cult revival of Druidry.

Who were the ancient Druids? Where did they come from, and what did they teach? The same questions were asked as far back as the days of ancient Rome, with interested individuals traveling to Britain to investigate.

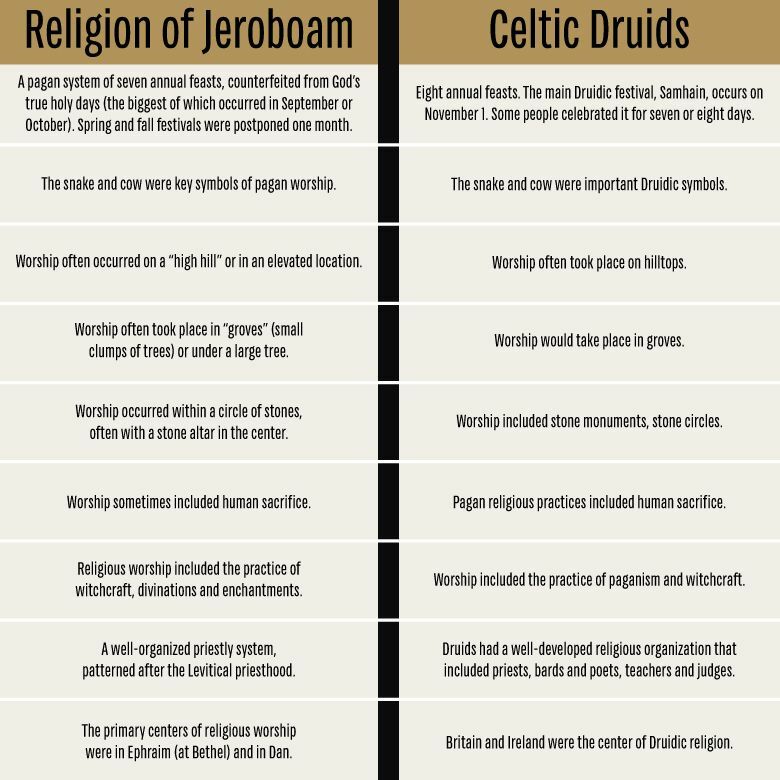

It may come as a surprise, but the Druid religion directly parallels in many ways that of the ancient pagan Israelite priests: from types of sacrifices to clothing to ritual locations to administration to festivals worshiped.

This begs the question: Were the Celtic Druids pagan Israelite priests? Let’s examine one of the key origins of ancient, institutionalized Israelite paganism and how it relates to biblical and secular evidence of deportation and migration of the Israelites up into ancient Europe.

Meet King Jeroboam

When King Solomon died c. 940 b.c.e. Israel was a powerful kingdom. Solomon left Israel to his son, Rehoboam, who dealt harshly with the people, even dramatically raising taxes. King Rehoboam’s cruel leadership provoked a revolution. In 1 Kings 12, the chapter that describes these events, the term “Israel” refers to 10 specific tribes. Verse 19 says that Israel “rebelled against the house of David unto this day.”

The rebellion was led by Jeroboam, a prominent leader from the northern tribe of Ephraim (verse 20; 2 Chronicles 10:3). Following the revolt, Jeroboam was made king “over all Israel.”

This was the moment Israel split into two kingdoms. The northern kingdom, situated in the region of Samaria, the Bible continued to call “Israel.” This kingdom consisted of 10 tribes and was led by King Jeroboam. The southern kingdom, named Judah, consisted of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin, as well as the Levites. Judah was led by King Rehoboam, and its headquarters remained in Jerusalem.

These two kingdoms, though family, became archrivals.

King Jeroboam didn’t bask in success for long. Securing the allegiance of 2 to 3 million disgruntled Israelites was easy; he now faced the challenge of keeping it. His people were accustomed to looking to Jerusalem, to the temple priesthood and the Davidic monarchy, for leadership. Under kings David and Solomon, the government displayed strong, stable leadership, politically, religiously and culturally.

Israel’s new king knew this would have to change, and quickly. Jeroboam’s immediate goal was to sever his people’s connection to Jerusalem, lest they gravitate back to Judah and its capital (1 Kings 12:26-27). To do this, Jeroboam invented an independent political and religious system in Israel.

Read for yourself what King Jeroboam told his people: “It is too much for you to go up to Jerusalem: behold thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt” (verse 28; King James Version). The king told his people, “Stop looking to Jerusalem, embrace this new political-religious system I have developed for you!”

So, what did King Jeroboam’s counterfeit political-religious system look like?

The Religion of Jeroboam

Like all good counterfeiters, King Jeroboam relied heavily upon the original product for inspiration. Basically, he took Israel’s existing religion and refashioned it to his own liking, adding in doses of paganism that he had gleaned from Egypt (where he had lived—1 Kings 12:2) and surrounding Gentile nations. His strategy was effective. To the Israelites, King Jeroboam’s political-religious system was similar enough to the one in Jerusalem to be believable. The people embraced it and never looked back.

You can see some of the specific beliefs and practices of Jeroboam’s religion in the accompanying table (further down). Let’s notice some especially pertinent details.

1 Kings 12:31 says that Jeroboam “made houses of high places, and made priests from among all the people, that were not of the sons of Levi.” The Hebrew word for house here means palace or temple. Jeroboam didn’t want his people looking to the temple in Jerusalem, so he built a counterfeit temple in Samaria. Notice, he then filled that temple with “priests of the lowest of the people.” King Jeroboam recognized the tremendous value of the temple and the Levitical priesthood, which God created and King David established in the united kingdom of Israel. Jeroboam created his own priesthood of ministers, musicians and poets.

Verse 32 continues, “And Jeroboam ordained a feast in the eighth month, on the fifteenth day of the month, like unto the feast that is in Judah, and he went up unto the altar ….” Jeroboam established his own holy day system, but it was patterned after the holy day system practiced in Judah. It was a perverted form of the true religion.

Notice. In Leviticus 23:34 God had established the timing of when Israel was to keep the Feast of Tabernacles, commanding, “the fifteenth day of this seventh month is the feast of tabernacles ….” King Jeroboam kept his feast of tabernacles one month later. (Keep this in mind.)

King Jeroboam also replaced worship on the Sabbath with worship on Sunday. In Hosea 2:13, God condemns Israel for practicing the religion of Jeroboam, which included replacing God’s Sabbath and holy days with “Her feasts, her new moons, and her sabbaths, And all her appointed seasons.”

King Jeroboam promoted idol worship, and created a number of pagan idols, many of them taken from Egypt and the surrounding Gentile peoples. He turned his people to these false gods, even claiming that these pagan gods were responsible for releasing Israel from Egyptian captivity (1 Kings 12:28; here he chooses gods with a familiar place in the heart of early Israel. See Exodus 32).

King Jeroboam reigned for 22 years, during which he deeply entrenched his political-religious system in Israel. We know Jeroboam’s religious system survived because biblical passages such 2 Kings 17 show it to be alive and thriving more than 200 years after his death! Verse 22 describes Israel’s condition toward the end of the eighth century b.c.e.: “And the children of Israel walked in all the sins of Jeroboam which he did; they departed not from them.” What Jeroboam created became the national religion of the northern kingdom. Throughout the history of this kingdom, the Bible repeatedly condemns the Israelites for following in this “way of Jeroboam.” In fact, 15 of Israel’s 18 kings are specifically named as perpetuating Jeroboam’s “way.”

In 2 Kings 17:10 we read that practitioners of Jeroboam’s religion “set them up images and groves in every high hill, and under every green tree” (kjv). The Hebrew term for images means “a column or memorial stone.” Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon says it means “something set upright, specially: a) a pillar … b) a statue, the image of an idol, e.g. the statue of Baal.” The Israelites also worshiped in “groves in every high hill, and under every green tree.” The term groves refers to a place marked by trees. Often, as the scripture clearly says, they would gather under one large tree. (Groves can also refer to the pagan goddess, Asherah.) They also constructed worship places at the summit of “high hills.”

Verses 16-17 provide further documentation: “[A]nd they forsook all the commandments of the Lord their God, and made them molten images, even two calves, and made an Asherah, and worshipped all the host of heaven, and served Baal; and they caused their sons and their daughters to pass through the fire, and used divination and enchantments, and gave themselves over to do that which was evil in the sight of the Lord, to provoke Him.”

The Israelites were deeply immersed in the practice of “divination” and “enchantments,” which means sorcery, witchcraft, fortune-telling, and looking to heavenly signs and omens. In fact, their religion had become so depraved they were practicing human sacrifice using their own children.

By the late eighth century b.c.e., the religion of Jeroboam was so entrenched—and the Israelites were so unrepentant, even rejecting multiple warnings from God’s prophets—that God was left with no choice but to intervene and punish Israel severely. “And the children of Israel walked in all the sins of Jeroboam which he did; they departed not from them” (2 Kings 17:22). The primary reason for Israel’s punishment, destruction, and deportation was the unrepentant, pervasive practice of the religion of Jeroboam!

But remember: Despite their rebellion and although they didn’t look like it at the time, these people were God’s chosen people, a once-great cluster of tribes that God Himself had established and loved and had been working with for nearly a millennium!

2 Kings 17 discusses Israel’s besiegement, capture and destruction by the Assyrians (721–718 b.c.e).

“[U]ntil the Lord removed Israel out of His sight, as He spoke by the hand of all His servants the prophets. So Israel was carried away out of their own land to Assyria, unto this day” (verse 23).

The Bible couldn’t be clearer! Millions of Israelites, a people deeply steeped in the religion of Jeroboam, were literally “carried away” to the land of Assyria. The Bible describes the Israelite deportation to up as far as northern Iran (e.g. 2 Kings 17:6). The Israelites settled around this northeastern region for a time, but evidence points to a continued migration toward Western Europe.

Among other proofs for this migration, there is tangible evidence of the religion of Jeroboam being practiced in Western Europe and, even more so, in the British Isles!

Celtic Druidism

The Oxford Dictionary defines a Druid as “a priest, magician or soothsayer in the ancient Celtic religion.” The common perception today is that the Druids were a relatively small and insignificant class of people, and that ancient Druidism was an obscure religion, not widely practiced and without influence. This perception is false.

In Celt, Druid and Culdee, Isabel Hill Elder writes: “The popular belief that Druidism was the religion of ancient Britain and nothing more is entirely erroneous. Druidism was, in fact, the center and source from which radiated the whole of organized civil and ecclesiastical knowledge and practice of the country …. The truth about the Druids … is that they were men of culture, well educated, equitable and impartial in the administration of justice” (emphasis added).

Druidism was in fact the defining religion of the Celts, the people who lived in the British Isles, including Ireland, before the arrival of the Romans in the first century c.e.

Druidism arrived in the British Isles in waves; however, historians agree that it was entrenched and thriving by the third century b.c.e. Prior to the arrival of the Romans, Druidism, though localized, was an elaborate and well-developed system of government, law and education. Druids were the leaders of local societies; the guardians of the law, politics and culture; and the chief musicians and artists.

The Encyclopedia Britannica introduces the Druid as a “member of the learned class among the ancient Celts. They seem to have frequented oak forests and acted as priests, teachers and judges.” Isn’t it interesting that Druid priests were also judges, teachers and even poets and musicians? This was similar to the Levitical priesthood established in Israel, which we know King Jeroboam counterfeited (1 Chronicles 23:3-5).

There are various forms of Druidism, and there are differences in the practices, customs and beliefs between the various forms. Most, however, recognize eight annual feasts. (God established seven annual holy days in ancient Israel). The four primary Druidic festivals are Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane and Lughnasadh. The four minor feasts revolve around the movement of the sun (winter solstice, spring equinox, summer solstice, and fall equinox).

For many Druids, Samhain was the most important festival. This festival was celebrated on November 1, though some people celebrated it for seven or eight days. Recall what King Jeroboam did with the seven-day Feast of Tabernacles that God inspired, which generally falls sometime during the months of September and October? He postponed it by one month!

Historical records show that the Druids worshiped in stone and timber circles, or henges, which were often situated on a high hill. Ireland and the United Kingdom today are littered with stone henges of all shapes and sizes. (Timber henges are rare due to decomposition.) There are well over 100 such ancient stone circles. Elder discusses these: “The gigantic monoliths placed in circles and the piles of stones were alike unhewn. These piles, called si’uns or cairns, and in the north of England known as laws or lows, were usually placed on the summit of hills and mounds. … The similarity of si’un with the Hebrew word Zion (fortress), the Mount of Stone (as the name Zion in Celtic means), is striking.”

Most stone henges have been dated to before Israel’s Assyrian captivity. Historians have wondered about their early relevance to Druid practices, since they date long before the earliest written records of the Druids (still, dating for these types of monuments can be quite difficult to ascertain). How to explain this? Historical records show that many Celts traced their ancestry all the way back to Egypt and the Israelites’ captivity in Egypt (circa 1600 b.c.e.). After the Exodus, there is certain evidence to suggest that some Israelites, mainly from the tribe of Dan, separated and set off for the British Isles. (Recent discoveries have also affirmed trade during the judges period between Israel and Cornwall.) The Bible also records that the patriarchs and early Israelite leaders such as Moses and Joshua also used stone monuments and altars (e.g. Genesis 31:45-46; Joshua 4:19-21). This history requires another article, but the point is: There was contact with the British Isles during the pre-monarchical period (e.g. Judges 5:17).

Druids also worshiped in groves, or clumps of trees. Oak trees were especially appealing and an important part of religious worship. In Age of Fable, 18th-century author Thomas Bulfinch wrote:

These sacred circles were generally situated near some stream, or under the shadow of a grove or wide-spreading oak. In the center of the circle stood the Cromlech, or altar, which was a large stone, placed in the manner of a table upon other stones set up on end. The Druids had also their high places, which were large stones or piles of stones on the summits of hills. These were called Cairns, and were used in the worship of the deity under the symbol of the sun.

This reads almost precisely like the Bible verses condemning the practices of pagan Israel. The Druids worshiped in the same manner as the Israelite practitioners of Jeroboam’s religion.

Among the various Druidic symbols, the snake and the cow were especially important. In Mysteries of the Druids, written in 1861, Winwood Reade wrote, “[T]he Druids worshiped the heavenly bodies, and also trees, and water, and mountains, and the signs of the serpent, the bull and the cross.” The serpent and cow featured heavily in Jeroboam’s religion as well (2 Kings 18:4; 1 Kings 12:28-30). Further, the serpent was known as a symbol of the Tribe of Dan; the bull, of Ephraim (the two tribal centers of Jeroboam’s worship). Jewish tradition holds that these were the symbols displayed on Dan and Ephraim’s tribal flags (Numbers 2).

Archaeological excavations in Britain have uncovered the remains of sheep, goats and cows at Druidic sites. These animals were obviously used in sacrifices. But notice: These are all “clean” animals. The Druids—and King Jeroboam before them—could have learned about “clean and unclean meats” from only one place: righteous Israel! (See Leviticus 11.)

Roman records, specifically the writings of Julius Caesar, indicate that at least some Druids conducted human sacrifices. As we read earlier, this too was a practice of the religion of Jeroboam.

It is also fascinating to consider the way the Druidic ministry was organized in various orders. In How the Gospel Came to Britain, Brian Williams writes: “One class was concerned strictly with the priestly or sacrificial office. There was another class which were considered prophets and were occasionally employed at the altar, but with a special duty of the composition of music and sacred hymns. A third strictly secular class was occupied in composing and reciting poetry for the encouragement of virtue and condemnation of vice. A fourth class was devoted to astrology, sorcery and occultism. The priesthood was hereditary, but the chief Druid was elected.”

Again, compare that with the Bible’s description of how King David organized the Levites in 1 Chronicles 23 and 24. Under God’s direction, David divided the Levites into departments, or “courses.” These included “officers and judges,” “porters,” singers and musicians, and departments responsible for even more specific functions.

Archaeological excavations in the British Isles have uncovered the remains of Druid priests. Along with the skeletal remains, priestly garments—intricately designed clothes of amazing patterns and colors, studded with precious stones—have also been found. From whom did the Druids, and Jeroboam before them, learn about priestly garb? Again, from the high priests in righteous Israel! Passages such as Exodus 28:15-21 show the high priest wearing a white robe and a golden breastplate set with 12 precious jewels.

Records show that the Druids perpetuated their religion and government through a well-developed system of education. There were educational institutions, or colleges, spread throughout the British Isles. Elder wrote that when the Romans invaded there were “40 Druidic centers of learning” and that these “40 colleges were each presided over by a chief Druid.” During the time of Julius Caesar, people were traveling from Europe to the British Isles to be educated in Druidic colleges. But where did the Druids, and King Jeroboam before them, get the idea of institutionalized education?

Once again, from righteous Israel! The Bible clearly reveals that Samuel the prophet established a sophisticated, well-ordered system of education in Israel during the late 12th century and 11th century b.c.e. (1 Samuel 19:18-24; 2 Kings 2:3-15). Samuel had three colleges, and probably hundreds of students, “sons of the prophets.” King David himself was educated by Samuel and probably attended one of these colleges.

The Arrival of Christianity

What happened when Roman Christianity began to arrive in the British Isles in the late first century? Was Celtic Druidism eradicated? Was it absorbed into British Christianity? The answer is: both!

Elder writes: “Upon the introduction of Christianity the Druids were called upon, not so much to reverse their ancient faith, as to ‘lay it down for a fuller and more perfect revelation.’

No country can show a more rapid, natural merging of a native religion into Christianity than that which was witnessed in Britain in the first century a.d. The readiness with which the Druids accepted Christianity, the facilities with which their places of worship and colleges were turned to Christian uses, the willingness of the people to accept the new religion are facts which the modern historian has either overlooked or ignored.

In The Offshore Islanders, historian Paul Johnson describes how Britain’s Christianity has always been distinct from Roman Christianity. Johnson calls it a “Celtic Christianity,” and it was prominent—in various forms and often localized—throughout the British Isles, especially Wales, Scotland and Ireland, before the large-scale arrival of Roman Catholicism in the late seventh century. Celtic Christianity was essentially a blend of Celtic religion and tradition and Christianity.

One of the key examples of this is the worship of Halloween. For more detail on this topic—and it’s fascinating, multifaceted connection to Jeroboam’s religion—see our article “Halloween—In the Hebrew Bible?”