Elephantine Papyrus: Proving the book of Nehemiah

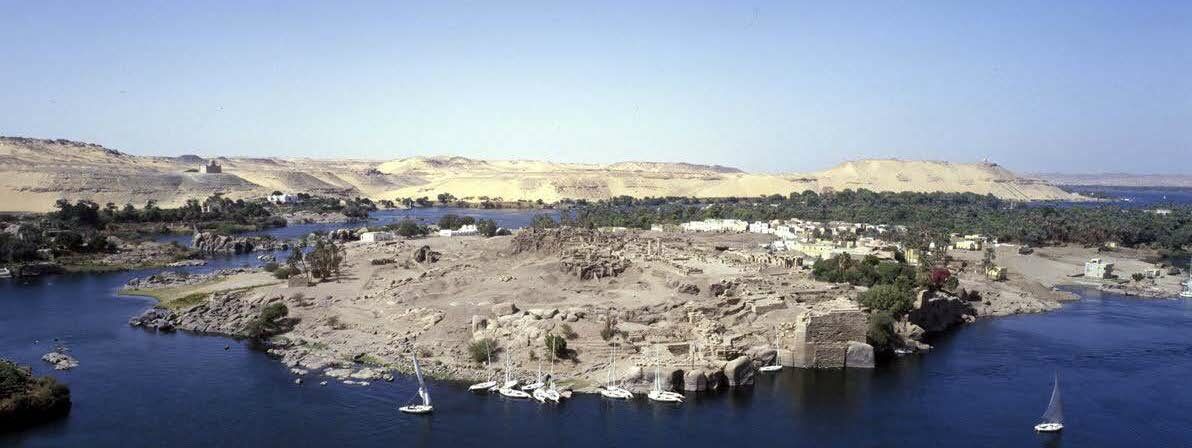

Some 2,500 years ago, a peculiar Jewish outpost stood guard deep in the land of Egypt, on an island fortress within the Nile River. Today, modern excavations at this fortress have uncovered evidence adding to the historicity of the Bible.

Preserved by Egypt’s sandy, dry desert climate, the Elephantine Papyri are a collection of 175 documents, thousands of years old. These documents were uncovered during excavations at this ancient Elephantine fortress.

One papyrus letter caused particular excitement. This letter, unearthed in 1909, contains 30 lines of inked Aramaic text, dating to circa 407 b.c.e. Known as Elephantine Papyrus No. 30, or the Elephantine Temple Papyrus (pictured above), this document contains proof of two biblical figures in particular: Jehohanan the high priest and Samaria’s governor, Sanballat the Horonite.

Jewish Community in Elephantine

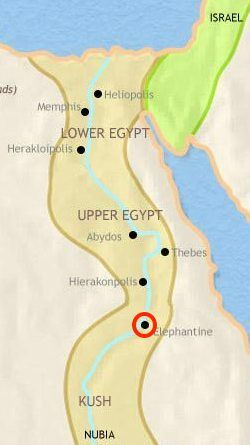

As stated above, Elephantine was a Jewish military outpost located on a Nile River island deep within southern (Upper) Egypt. There is much debate as to the origin of this community. The best guess appears to be sometime during the reign of King Manasseh—middle of the seventh century b.c.e. The second-century b.c.e. Letter of Aristeas records that “large numbers of Jews had come into Egypt with the Persians, and in an earlier period still others had been sent to Egypt to help Psammetichus in his campaign against the king of the Ethiopians [Nubians].” It appears that following Psammetichus i’s campaign against the Nubians, a Jewish outpost was left to guard the southern part of Egypt. (Psammetichus had enlisted the help of several foreigners in his army.)

As Prof. Bezalel Porten wrote in the May-June 1995 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review:

The Jewish community at Elephantine was probably founded as a military installation in about 650 b.c.e. during Manasseh’s reign. A fair implication from the historical documents, including the Bible, is that Manasseh sent a contingent of Jewish soldiers to assist Pharaoh Psammetichus i (664–610 b.c.e.) in his Nubian campaign and to join Psammetichus in throwing off the yoke of Assyria, then the world superpower. Egypt gained independence, but Manasseh’s revolt [against Assyria] failed; the Jewish soldiers, however, remained in Egypt.

Because of the assistance Manasseh provided Egypt, the pharaoh likely allowed the Jews to maintain a presence at the Elephantine fortress. And due to the political situation in Judah, they may not have been able to return easily. Manasseh was an incredibly evil king, who partway through his reign was taken captive by Assyria (and is mentioned in the ancient Assyrian records).

The Elephantine “Jewish” community is unusual in that it kept very few biblical customs, and although they worshiped at a temple somewhat resembling Solomon’s in layout, biblical law forbade the establishment of such an edifice. Further, the Elephantine Papyri show the community used the Aramaic language rather than Hebrew. This has bewildered scholars. One theory is that these Jews were originally from a northern community located in Syria (perhaps something like the northern Judahite outpost mentioned in 2 Kings 14:28). Perhaps this community was also made up of the pagan Samaritan contingent, which had replaced the northern kingdom of Israel after its final defeat in 718 b.c.e. In any event, the state of religion during the reign of Manasseh was arguably worse—more bloody—than that of the surrounding heathen nations, so it should not be a surprise that the religious practices at Elephantine would be “Jewish” in name only.

Herodotus described this fortress in his Histories: “In the reign of Psammetichus, there were watchposts at Elephantine facing Ethiopia, … And still in my time the Persians hold these posts as they were held in the days of Psammetichus; there are Persian guards at Elephantine.” Persian governance and a Jewish community at Elephantine are both attested to in the Elephantine Papyrus. And it is to the Persian period that our key papyrus dates.

A Temple and a High Priest

Elephantine Papyrus No. 30 begins: “To Bagohi governor of Judah, [from] the priests who are in Elephantine the fortress.” The letter, a copy of the official dispatch that was sent to Jerusalem, discusses the temple of “yhw” (a form of the Hebrew yhwh) that had been built at the Elephantine fortress and a request for permission to rebuild it after its destruction by Egyptian troops.

That Vidranga, the wicked, [in] a letter sent to Naphaina his son, … [wrote]: “The temple which is in Elephantine the fortress let them demolish.” Afterwards, Naphaina led the Egyptians with the other troops. They came to the fortress of Elephantine with their implements, broke into that temple, demolished it to the ground, and the pillars of stone which were there they smashed.

The papyrus continues: “[W]e sent a letter [to] our lord, and to Jehohanan the high priest and his colleagues the priests who are in Jerusalem, and to Ostanes brother of Anani and the nobles of the Jews.” Jehohanan is a longer version of the name “Johanan,” son of Eliashib the high priest, who served during the time of Ezra and Nehemiah. (This same Johanan is mentioned in Ezra 10:6 and Nehemiah 12:22-23.)

Of this High Priest Jehohanan, the first-century c.e. historian Josephus records some intrigue. Apparently, there had been a falling out between Jehohanan and Bagohi (the governor addressed at the start of the letter, who had probably taken over from Nehemiah himself). Josephus records that Bagohi intended to install Jehohanan’s brother, Jeshua, in his stead as high priest. Jehohanan and Jeshua argued in the temple, and in a fit of rage Jehohanan killed his brother. Josephus relates that in divine punishment, the Jews were enslaved and the temple desecrated by the Persians (Antiquities of the Jews, 11.7.1.). Some evidence of the dispute can be gleaned from the papyri—while the Elephantine Jews appeal to both Bagohi and Jehohanan, the reply from Bagohi approving the construction of the temple made no mention of the high priest.

Sanballat, Governor

Toward the end of the papyrus, it reads: “Moreover, all these things in a letter we sent in our name to Delaiah and Shelemiah, sons of Sanballat, governor of Samaria.” This Sanballat i the Horonite, governor of Samaria, is mentioned numerous times throughout the book of Nehemiah. He was a sworn enemy of the Jews who were attempting to rebuild the wall around Jerusalem under the leadership of Nehemiah. He was actually related to Jehohanan the high priest (Nehemiah 13:28—his daughter had married into the priestly family). Together with Tobiah the Ammonite and Geshem the Arabian, Sanballat attempted (unsuccessfully) to stymie Nehemiah’s efforts in reestablishing Jerusalem. “Sanballat sendeth, also Geshem … thinking to do to me evil” (Nehemiah 6:2; Young’s Literal Translation). The Wadi Daliyeh bulla also most likely refers to this Sanballat, with the broken inscription reading “…iah, son of […]ballat, governor of Samar[ia].” (There is a small chance, though, that this bulla could refer to a later Sanballat that ruled in the following century.)

The name Sanballat come from the Babylonian name Sinuballit, meaning “Sin [Sumerian moon god] has begotten.” The word Horonite is sometimes translated Harranite. Harran was an ancient city in Upper Mesopotamia near the modern border of Turkey and Syria. The Horonites were likely among those nations transported to Samaria to replace the Israelites who were deported by the Assyrians in circa 721–718 b.c.e. (2 Kings 17).

Sanballat was already governor of Samaria before Nehemiah’s first term in Judea beginning circa 445 b.c.e. The Jews from Elephantine, circa 407 b.c.e., requested help not from Sanballat, but from his sons Shelemiah and Delaiah. These names are found in numerous scriptures of this general time period. While it cannot be certain whether they refer directly to Sanballat’s sons, they do at least provide authenticity to the accurate period use of the biblical names.

The Elephantine Temple Papyrus is an intriguing document from an intriguing community, proving a number of biblical elements—most notably the existence of Nehemiah’s archenemy Sanballat and the High Priest Jehohanan. For more about the historicity of the book of Nehemiah, please read “Nehemiah: A Man and a Momentous Wall.”