Joab’s Tunnel?

Now David said on that day, “Whoever climbs up by way of the water shaft and defeats the Jebusites … he shall be chief and captain.” (2 Samuel 5:8; New King James Version)

Before King David’s conquest of the city, Jerusalem was occupied by the Canaanite Jebusites. The Jebusites believed that their city was so well fortified that even “the blind and the lame” could defend it. One of David’s men, Joab, led a unit into the city using the water tunnel—called tsinnor in Hebrew. By exploiting this weak point, the city was quickly conquered.

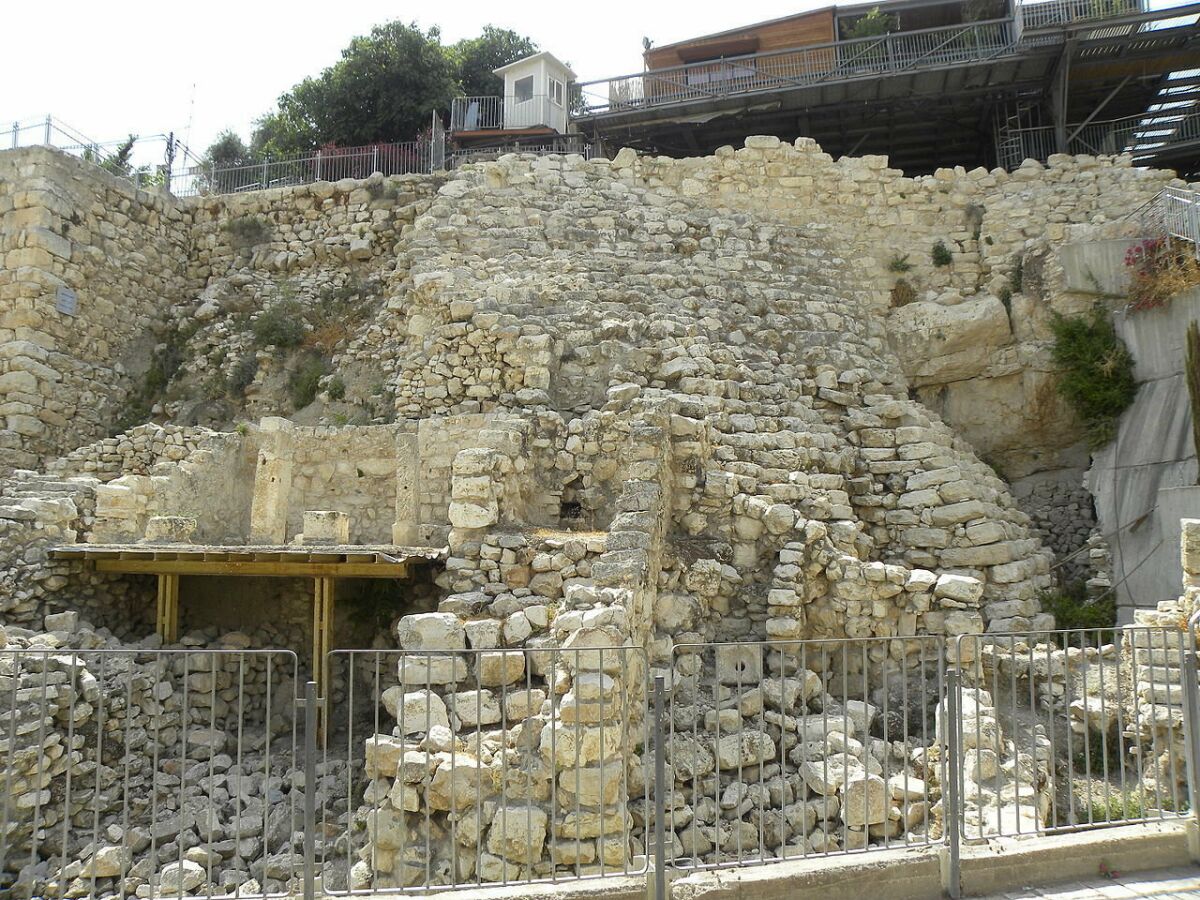

In 2008, during excavations around the top of the Stepped Stone Structure, archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar and her team discovered an opening into an ancient water tunnel.

The tunnel walls follow a natural cavity in the bedrock, running along the upper part of the eastern slope of the City of David. Dr. Mazar believes the tunnel was eventually integrated into the construction of the Stepped Stone Structure during the 10th century b.c.e., and was probably used to channel water to a man-made pool built on the southeast side of the palace, referred to in Nehemiah 3:16. (Interestingly, this pool is described as being near to a large “stepped” structure—see verse 15 and 12:37. It seems obvious that this refers to the Stepped Stone Structure.)

Layers of debris dating to the end of the First Temple period (sixth century b.c.e.) had buried the entrance to the tunnel. After stumbling upon the opening, Dr. Mazar investigated the narrow tunnel. She found that it ran from north to south and was wide enough for one person at a time to pass through.

“The tunnel’s characteristics, date and location testify with high probability that the water tunnel is the one called tsinnor in the story of King David’s conquest of Jerusalem,” said Dr. Mazar.

Both ends of the tunnel are blocked by debris and fallen stones, yet its as-yet-uncovered span still stretches over 50 meters. Dr. Mazar said that further excavation would require constructing proper reinforcements to support the subterranean structure.

“Toward the end of the First Temple period (sixth century b.c.e.), the tunnel was converted to an escape passage, perhaps used in a manner similar to King Zedekiah’s escape during the Babylonian siege (2 Kings 25:4),” Dr. Mazar wrote in a press release.

During this phase, additional walls were constructed in order to prevent the possibility of anyone entering the tunnel from the slope of the hill and to prevent the penetration of debris inside the tunnel. Complete oil lamps were found on the ground inside the tunnel, characteristic of the end of the First Temple period. These lamps testify to the tunnel’s last use.

Once the Babylonians laid siege upon the city c. 587 b.c.e., however, the tunnel was covered up and lost from world view—until now.

Dr. Mazar called the discovery “completely unexpected.” Because it was made near the end of a digging season—her last one to date in the City of David area—she believes there is much more to be learned about the passageway. “We have a general knowledge of the tunnel,” she said, “but we are far from having a complete picture.”

This tunnel is one of many incredible discoveries found in Dr. Mazar’s Jerusalem excavations, giving us greater insight into how ancient Jerusalem looked during the time of the kings—in particular, during the reign of King David.