Is Joshua Mentioned in the Amarna Letters?

The 14th-century b.c.e. Amarna Letters are often popularly identified as preserving record of the Israelite conquest of Canaan—at least among proponents of “early Exodus” schemes (putting the entry into Canaan circa 1406 b.c.e. or 1366 b.c.e., depending on whether one follows Masoretic or Septuagint chronology). Many of these hundreds of letters sent to the Egyptian pharaohs Amenhotep iii and Akhenaten from the rulers of Canaan beg for military help in defending against the mysterious invading Habiru people—a name strikingly reminiscent of the word Hebrew—who are taking “all the lands.”

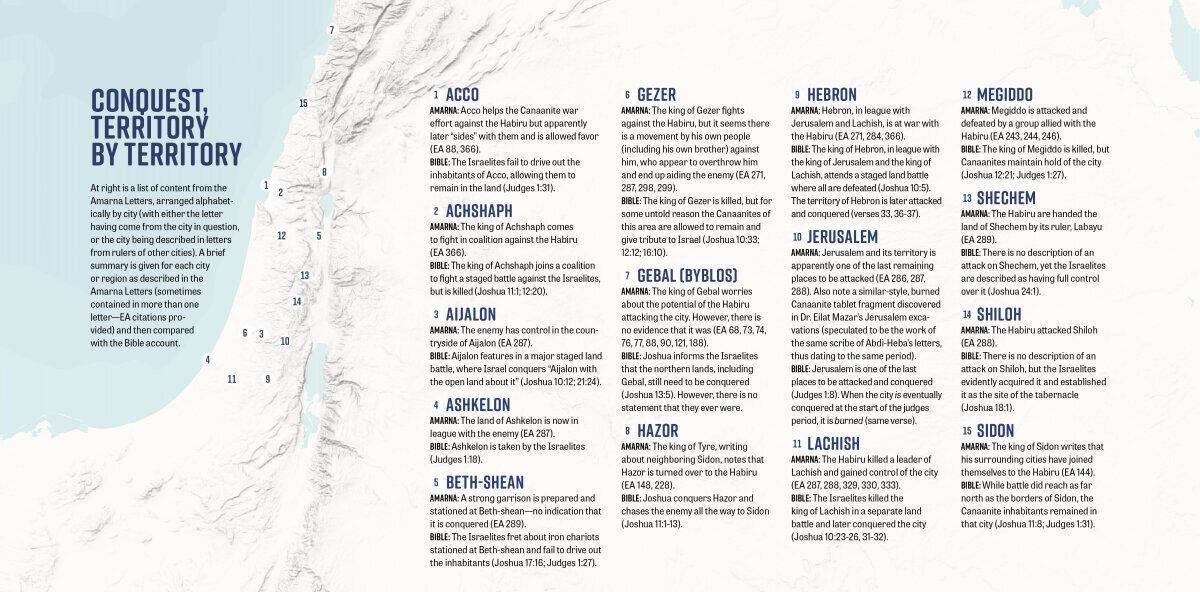

We have argued in past articles that the Amarna Letters do in fact contain a snapshot of the conquest of Canaan led by Joshua (see “The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?”, which highlights a city-by-city comparison of the Amarna and biblical texts to demonstrate the level of corresponding details). Important locations can be equivocated, but what can be said for the biblical personalities?

“Although the place names of the Amarna texts are parallel to those of the Old Testament, the personal names are totally different,” wrote Dr. Charles Pfeiffer in Tell El Amarna and the Bible (1963).

Yet there are personal names on the letters that are similar—including the name Joshua—and not on some damaged portion of text reconstructed in a contrived manner.

EA 256

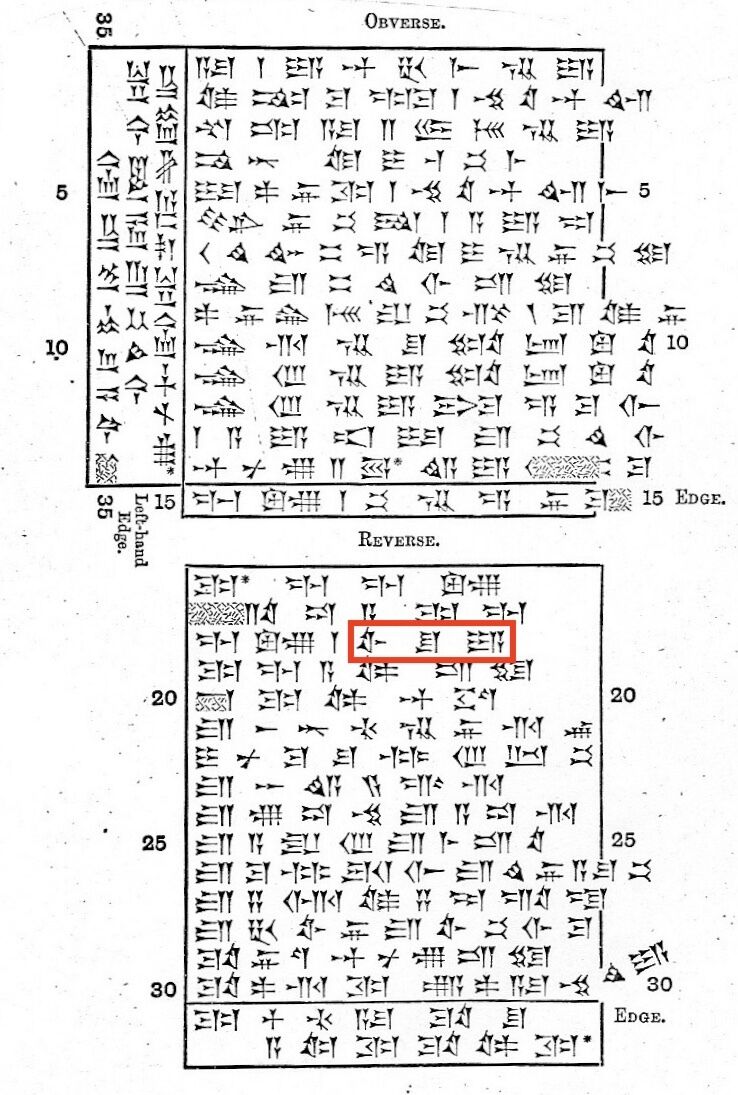

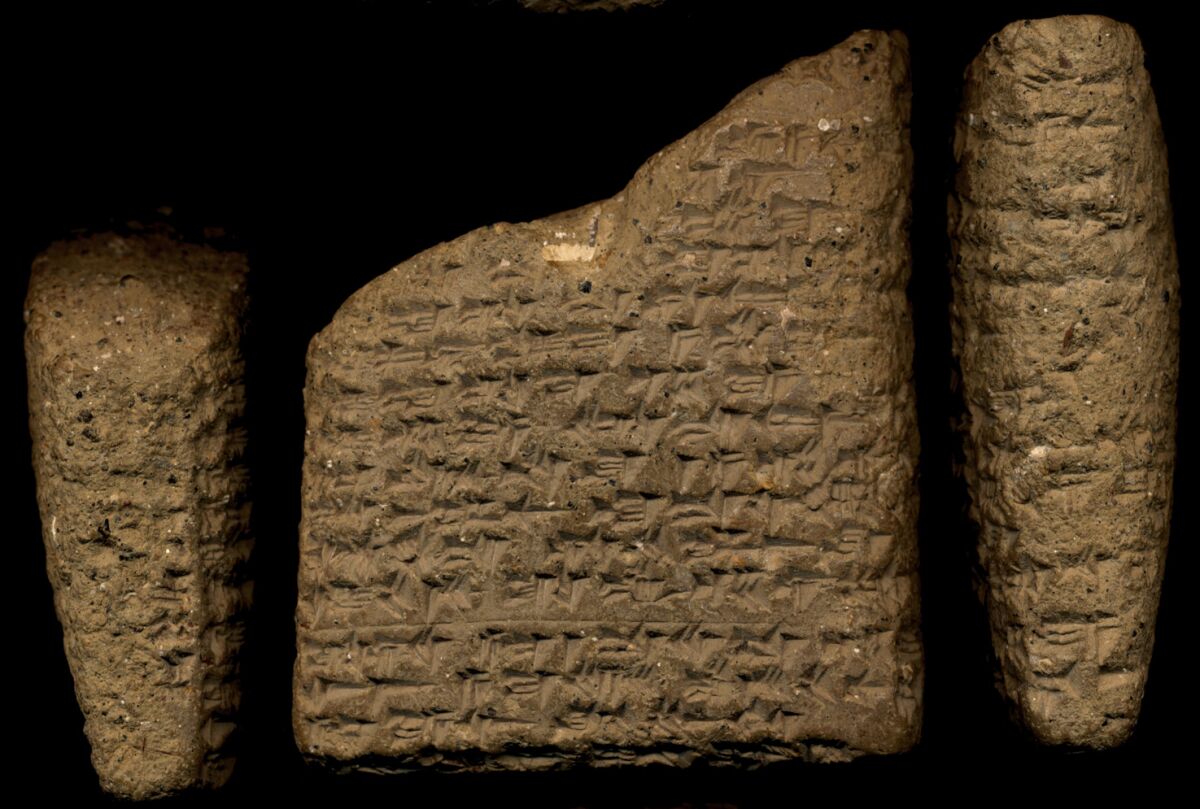

EA (El-Amarna) 256 is a square, cuneiform-inscribed tablet written by the Canaanite Mutbaal, son of Labayu king of Shechem, to the commissioner Yanhamu. In his letter, Mutbaal answers an accusation of providing safe-haven for one Ayyab, prince of Ashtaroth, who was wanted for caravan robbery.

A number of different names and cities are mentioned in passing in the letter. And the reverse side of the inscription introduces a striking figure: Yishuya (alternatively translated Yashuya or similar).

In the letter, Mutbaal diverts attention to this individual as having “[ro]bbed Šulum-Marduk” (per William Moran’s The Amarna Letters, 1992, page 309; translation by William Albright). Mutbaal accuses Yishuya’s forces of raiding the caravan of what appears to be a high-profile Babylonian merchant. (There are alternative renderings of this passage based on the fragmentary nature of the word translated “robbed”—the name remains the same, however.)

Of Yishuya, “Moran sees it as an abbreviated theophoric name composed of the root ישע,” Prof. Zipora Cochavi-Rainey writes in ‘To the King, My Lord’: Letters From El-Amarna, Kumidu, Taanach and Other Letters of the 14th Century B.C.E. (Hebrew translation ours). This root ישע is precisely that of the Hebrew name Joshua (יהושע, Yehoshua, or the contracted variant ישוע, Yeshua). The transliteration of the name in Mutbaal’s letter as Yishuya or Yashua is strikingly similar to that of Joshua, leading some to see the names as one and the same. Assyriologist Albert T. Olmstead is a case in point. In his 1931 History of Palestine and Syria, he wrote: “‘Ask then Benenima, ask then Tadua, ask then Iashuia.’ Benenima is a perfectly good Benjamin, Iashuia is an equally good Joshua!” Cochavi-Rainey likewise notes the obvious similarity; although in no uncertain terms, she immediately follows the aforementioned sentence with the strict warning to the reader: “But to equivocate Yašuya with Joshua—don’t even mention it.”

I’m not so easily dissuaded.

Not all agree on this name as the best representation of Joshua. W. F. Albright, for example, believed Joshua’s name would have been transliterated differently, writing that it “would probably be written something like Ya-ḫu-šu-uḫ” (“Two Little Understood Amarna Letters From the Middle Jordan Valley,” 1943). The question of how a Canaanite “should” have spelled the name Joshua in logo-syllabic cuneiform of the Late Bronze Age wades into a significant level of speculation, however.

Of this Yishuya, we get little detail (again, depending on the translation of the surrounding context, which varies significantly—others end the train of thought with only passing reference to his name, and begin a new one concerning Šulum-Marduk). Interestingly, in his article “A Canaanite-Babylonian Caravan Venture: A Note on EA 255 and 256,” Pinhas Artzi—while not commenting on the identification of this individual—at least draws attention to a passage in the book of Joshua in loose relation to Šulum-Marduk as a Babylonian goods merchant. “On some evidence of continuity in this ‘Babylonian line’ we may learn something from Joshua 7:21,” he wrote. “In his confession, Achan enumerates among his spoil: ‘אדרת שנער אחת טובה,’ ‘a fine Shinar mantle.’ As it was identified by Veenhof (1972: page 102, n. 174), this is a Hebrew translation … of the Akkadian (actually Old Assyrian) merchandise-listing: … ‘one Akkad-made/style overcoat/blanket of good quality.”

At the end of the day, it remains speculative as to whether or not this Yishuya is one and the same Joshua from the biblical account. It is nevertheless striking to see such a name within a corpus already infamous for its connection to the conquest account—with the Habiru taking swathes of territory in Canaan. In EA 288, the Canaanite ruler of Jerusalem lamented to the pharaoh: “May the king [pharaoh] give thought to his land; the land of the king is lost. All of it has attacked me. … I am situated like a ship in the midst of the sea …. [N]ow the Habiru have taken the very cities of the king. Not a single mayor remains to the king, my lord; all are lost.”

Yishuya is far from the only biblically linked personal name found in the texts. Others proposed include: “Judah,” “Malkiel” and “Heber” (see here for more detail). Albright even offered the above-mentioned Yanhamu as an individual “possibly of Hebrew origin” (Ancient Near Eastern Texts, 1955, page 486).

So again: Is Joshua mentioned in the Amarna Letters? A Joshua is; it could justifiably be said. The Joshua? For now, we can only speculate.

Some Concluding Thoughts

Suffice it to say, identifying the Habiru of the Amarna Letters as the Hebrews of Joshua’s day remains highly debated. Scholars are significantly more reticent than they once were to draw such biblical parallels; additionally, proponents of late-date Exodus schemes (which put the conquest at least a century after the Amarna period—Albright falls into this category) argue that the Amarna Letters could not relate to the events of Joshua’s day and that any similarities that do exist must be merely coincidental.

Recently, Joel Kramer’s popular channel, Expedition Bible, uploaded a new video arguing that the Amarna Letters do describe the Israelite conquest (see “No. 1 Evidence for Israel’s Conquest of the Promised Land … Other Than the Bible!”). This was swiftly followed by a rejoinder from Dr. Jordan Jones on the channel Bible and Archaeology, with his own video titled “No, the Habiru Weren’t the Ancient Israelites.” Opinion was split in the comments on the latter’s rebuttal, with some praising it while others characterized it as “willful blindness to evidence.”

While disagreeing with some elements of Kramer’s presentation, I think such rebuttals from Jones and others fall into the trap of straw-manning—ridiculing the notion that all Habiru are Israelites—instead of engaging with the real argument—that the biblical term Hebrew is cognate with Habiru and that, while the conquest-period Israelites can be identified as Habiru/Hebrews, not all Habiru/Hebrews are necessarily Israelites.

This, in turn, answers the question posed by Jones: “What do you do with the references [to the Habiru] from the 19th century [b.c.e.]? What do you do with them? If all you want to say is, 14th century, biblical idea of a conquest, and you’ve got a pair, you have to also deal with that”—here he is referring to the mention of Habiru on certain texts throughout wider Mesopotamia back into the early first half of the second millennium b.c.e.

In fact, the existence of this term in the 19th century b.c.e. only strengthens the association—for the first biblical mention of the term “Hebrew” is nestled precisely at this chronological point in time, in reference to “Abram the Hebrew” (Genesis 14:13)—long before the existence of any Israelites. (Compare also the use of the term in Genesis 39:14-17 and 41:12.) Albright himself wrote that “there is much reason to identify them [the Habiru] with the Hebrews of the Patriarchal Age” (op cit).

At the end of the day, we have dramatic testimony from the 14th century b.c.e. of abject terror and conflict in Canaan—one might justifiably call it conquest—wrought by a similarly classified people to similarly named places in a similar timeframe—with individuals themselves bearing similar personal names.