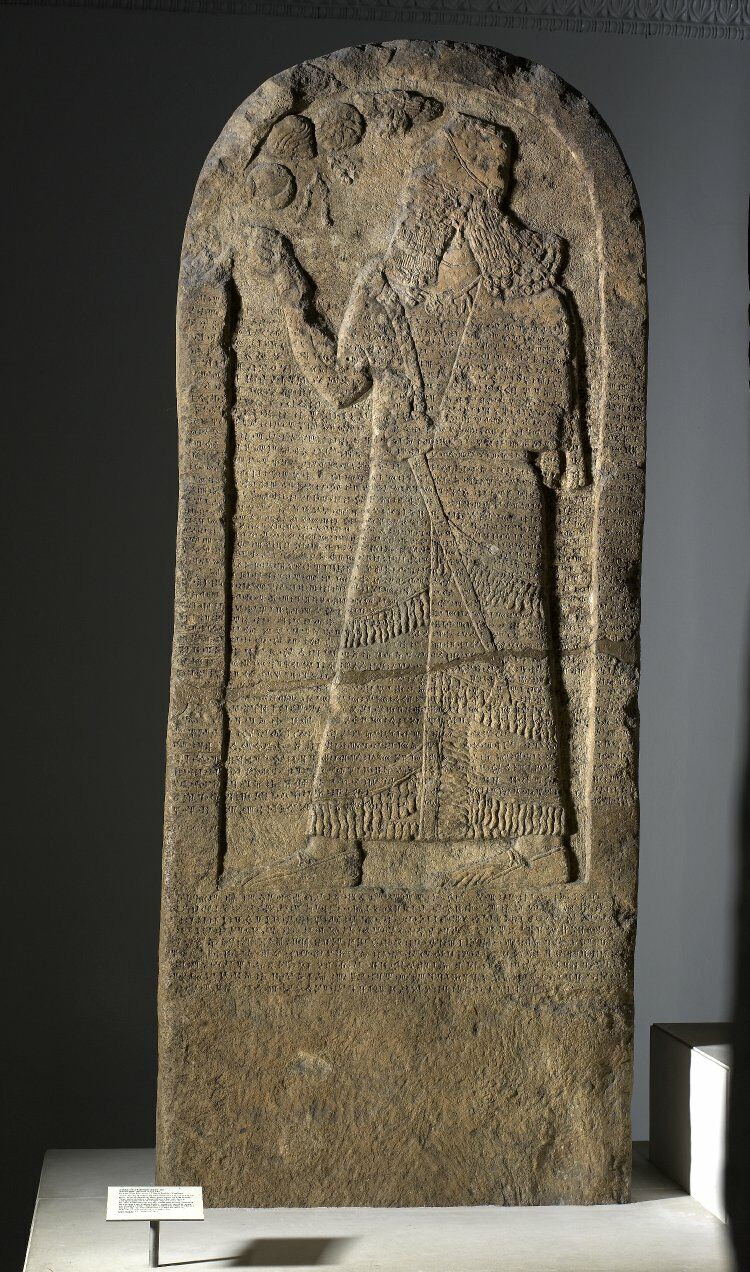

The Kurkh Monolith Confirms King ‘Ahab the Israelite’

The Kurkh Monolith, or Stele of Shalmaneser iii, was discovered in 1861 by John G. Taylor in the present-day city of Üçtepe, Turkey. Its less popular counterpart, the Stele of Ashurnasirpal ii, was discovered by Austen Henry Layard at Kahlu, or Nimrud, in present-day Iraq. The Kurkh Monolith confirms the existence of an Israelite king, mentions the name of a biblical king of Syria, provides evidence of peaceable relations and military cooperation between Israel and Syria, and demonstrates the strength of the Northern Kingdom of Israel in the early ninth century b.c.e.

Now on display in the British Museum, these artifacts tell an intriguing 2,800-year-old story of Israel’s resistance against an imperialistic Assyrian Empire.

Reigning from 883–859 b.c.e., Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal ii is credited with the establishment of the mighty Neo-Assyrian Empire. He consolidated the conquests of his father, he expanded the empire to the northwest, and he rebuilt the Assyrian city of Calah.

Although Ashurnasirpal did not come into direct contact with the Israelites, his conquests brought the Assyrians into the lands of the Phoenicians, a people who bordered and often traded with the Israelites. This expansion set the stage for conflict, but that battle would be left for his son, Shalmaneser iii.

Shalmaneser iii (858–824 b.c.e.) is well known for his military conquests in North Syria. These brought him into contact with Israel. After he defeated Hazael, king of Syria, he received tribute from the Phoenician city-states and the tribes of Israel. (Jehu’s submission to Shalmaneser is recorded on the Black Obelisk.)

The Stele of Shalmaneser iii describes his military campaigns in western Mesopotamia and Syria. It describes Shalmaneser’s victory at the battle of Karkar, situated in northern Syria, where he overthrew an alliance of 12 local kings. Shalmaneser had inscribed on the monolith:

Karkar, his royal city, I destroyed, I devastated, I burned with fire. 1,200 chariots, 1,000 cavalry, 20,000 soldiers, of Hadad-ezer, of Aram; 700 chariots, 700 cavalry, 10,000 soldiers of Irhulêni of Hamath; 2,000 chariots, 10,000 soldiers of Ahab, the Israelite.

According to this inscription, Israel’s King Ahab (1 Kings 16-22) was part of this coalition against the Assyrian army. This is one of only five known inscriptions with the name Israel; the others are the Merneptah Stele, the Tel Dan Stele, the Mesha Stele, and the Berlin Pedestal. (There is still some small scholarly disagreement about the Berlin Pedestal’s reference to Israel, due to the damaged nature of the inscription—the reading, however, is all but certain.)

The Stele of Shalmaneser iii also names another biblical king—Hadadezer of Syria. Though this king is not mentioned by name in the Bible, he is referenced in 1 Kings 22:3, 31 and 2 Kings 5 and 2 Kings 6:8-23.

The monolith also confirms the peaceful relations and military cooperation between Israel and Syria as spelled out in the Bible (1 Kings 20:31-34). King Ahab had overthrown Ben-hadad of Syria, who took 7,000 troops to lay siege on Samaria, the capital city of the northern kingdom of Israel.

Professor of Assyriology Daniel David Luckenbill states:

According to the prevailing interpretation of the Hebrew account in the light of the Assyrian records, the “two years” truce mentioned in 1 Kings 22:1 follow immediately upon the defeat of Benhadad at Aphek, and leave room for Ahab’s presence at Karkar.

When Ahab joined the confederation against Assyria, he brought an army of 10,000 foot soldiers and 2,000 chariots, a large military for the time period. The size of this force indicates that Israel was a considerable military power in the region during the early ninth century b.c.e. It also tells us that, since power is accumulated gradually, Israel would have been a mighty and rising power for a couple hundred years.

The Kurkh Monolith is an amazing artifact that confirms the Scriptures and adds new details to the historical account. It is a great example of how archaeology and the Bible function together to reveal the complete account of history. To understand more of the fascinating connections between archaeology, the Bible and the Assyrians, please visit our page dedicated to the Assyrians below. Also, please request a free copy of our full-color exhibit brochure, “Seals of Isaiah and King Hezekiah Discovered!”