Uzziah: Uncovering a King of Judah

He’s best known as the “Leprous King” and one of Judah’s longest-reigning monarchs. Despite his 52-year reign, however, the biblical account of his kingship is contained primarily in only two chapters of the Bible—2 Kings 15 and its parallel chronology, 2 Chronicles 26. Within the brief account of his reign, this fascinating king, identified by two different names, presided over a significant period of Judahite prosperity, made a fatal mistake in the temple, became a leper, and experienced one of the greatest-ever earthquakes to strike the nation.

Adding to this fascinating story is a trove of artifacts including seals, tablets and more, proving not only the existence of this king but also details of his reign.

Uzziah–Azariah: A Brief Chronology

“Uzziah” is the name used in the Chronicles account of this king, and both “Uzziah” and “Azariah” are used in the Kings account. There is no definite reason why this king bore two similar Hebrew names. Perhaps one was a given name and the other a throne name.

Uzziah began his long rule over Judah at the age of 16, during the reign of King Jeroboam of Israel. His father, Amaziah, reigned over a turbulent time in Jewish-Israelite relations—conflict between both sides had resulted in Jerusalem being ransacked and destroyed by the Israelites. Uzziah’s father was later murdered at Lachish.

Uzziah’s rule, on the other hand, marked a time of growth and rebuilding for Judah. “And he did that, which was right in the eyes of the Lord” (2 Chronicles 26:4). Uzziah had many miraculous victories against the Philistines, and mounted a vast national rebuilding program. In a somewhat Solomonic manner, his fame spread throughout the surrounding regions.

“But when he was strong, his heart was lifted up to his destruction” (verse 16, King James Version). Uzziah made a fatal error: Despite the desperate pleading of more than 80 priests, the king entered the temple in order to burn incense on the altar before the Holy of Holies. Suddenly, leprosy broke out across the king’s face, and the priests quickly thrust him out. (The priest leading the protest against him was named Azariah—perhaps Uzziah came to be called Azariah because of this attempt to take on the priest’s position in offering incense.)

Uzziah remained a leper until the day of his death, living in an infirmary while his son Jotham stepped in as co-regent. During Uzziah’s rule, a ferocious earthquake hammered Judah and the surrounding region (some attribute this to his actions in the temple). This earthquake was so intense (for a region that experiences earthquakes with relative regularity) that it was used as a timestamp, as in Amos’s prophecy: “two years before the earthquake” (Amos 1:1).

Uzziah died in seclusion and was buried separately from Judah’s great kings. His son Jotham reigned in his place, governing righteously and continuing Judah’s prosperity.

Such is the brief biblical history of Uzziah. What does the scientific evidence say?

Seals of the Royal Servants

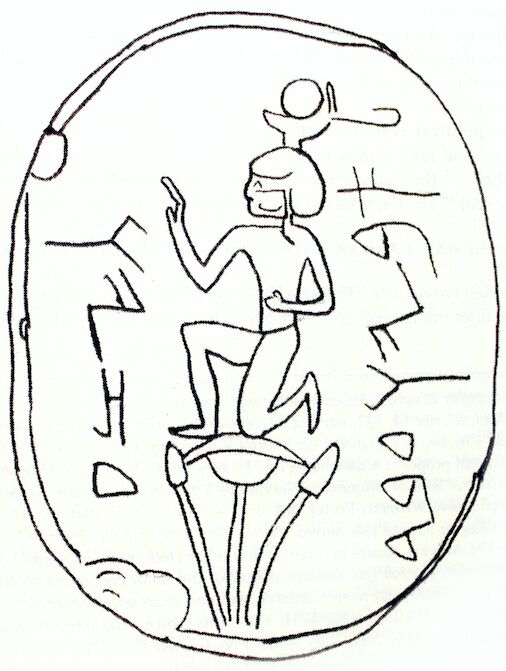

Two stone seals came to light in the mid-1800s, both belonging to high-ranking servants. Though the seals are unprovenanced, there is nothing to suggest they were forged. The inscription style on them fits within the specific eighth century b.c.e. time period. One seal is translated: “Belonging to Abijah, servant of Uzziah.” The other: “Belonging to Shebnaiah, servant of Uzziah.”

Both servants’ names, Abijah and Shebna (the short form of “Shebnaiah”), are found in the Bible. Not only that, both names are found in use during the specific century of Uzziah’s rule—eighth century b.c.e. (This is important, as certain names fall in and out of use during different biblical periods.) The seals, therefore, give us a small glimpse into Uzziah’s royal court.

An Earthquake: The Evidence

“Yea, ye shall flee, like as ye fled from before the earthquake In the days of Uzziah king of Judah,” so prophesied the Prophet Zechariah about the end time just before the coming of the Messiah (Zechariah 14:5). Archaeology has revealed an abundance of evidence for “Uzziah’s earthquake” (often called Amos’s earthquake due to the fact that he dates his message around it, and makes several references to earthquake-like destruction).

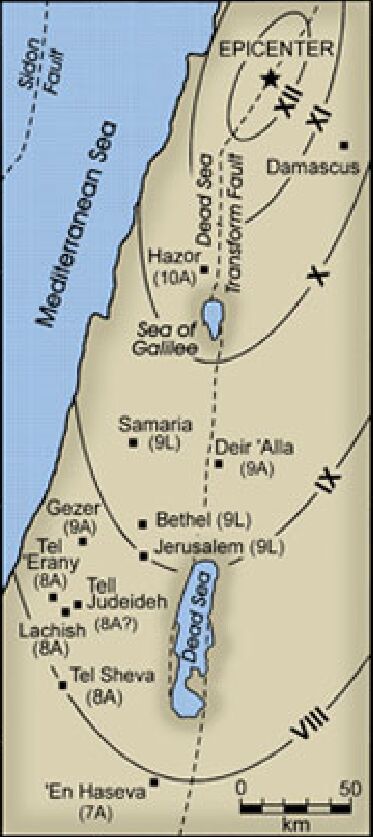

Archaeologists have found massive amounts of earthquake damage in sites throughout the ancient kingdoms of Judah, Israel and the Philistines. This earthquake damage dates to around 760 b.c.e., right around the latter third of Uzziah’s reign. Tilted walls, collapsed floors and more are attributed to this earthquake. So great is the amount of evidence, that scientists have been able to determine the epicenter was likely in Lebanon, and that its strength was probably around a magnitude 8.2, with a Modified Mercalli intensity of 9. Geologist Steven Austin, Ph.D., writes (emphasis added):

[This event] appears to be the largest yet documented on the Dead Sea Transform fault zone during the last four millennia. The Dead Sea Transform fault likely ruptured along more than 400 kilometers as the ground shook violently for over 90 seconds! The urban panic created by this earthquake would have been legendary.

The long duration of the earthquake—90 seconds—explains the Prophet Zechariah’s statement that people were “fleeing” while the earth was still rumbling.

There’s no telling the death toll from such a massive earthquake. We do have data, though, from earthquakes of somewhat lesser intensity that hit the region, from which we can get a loose picture. Two intensity-8 earthquakes occurred on the Dead Sea Transform fault—one in c.e. 749, killing 100,000 people, and one in c.e. 526, killing 255,000. And remember, the 760 b.c.e. earthquake was another intensity level higher!

Josephus wrote that this earthquake occurred while Uzziah was attempting to offer incense in the temple. He wrote that “a rent was made in the temple, and the bright rays of the sun shone through it, and fell upon the king’s face, insomuch that the leprosy seized upon him immediately.” He also claimed that a nearby mountainside collapsed, causing a significant landslide that destroyed roads and the king’s prized gardens.

Whatever the actual damage and death toll, the dating and general data of this quake powerfully back up the description of it by the prophets Amos and Zechariah.

Tiglath-Pileser III Weighs In

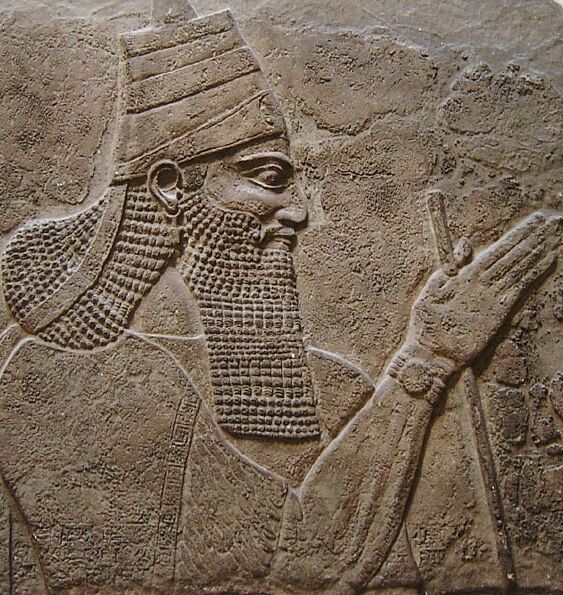

An interesting fragmentary inscription belonging to Tiglath-Pileser iii mentions several times “Azrijâu mât Jaudaai,” translated as “Azariah of Judah” (Uzziah’s secondary name). Pileser iii’s annals mention that in the first years of his reign (c. 740 b.c.e.), he led a campaign into Syria:

Nineteen districts of the town Hamath, together with the towns in their circuit, which are situated on the coast of the Western Sea, which in their sin and wickedness sided with Azariah, I turned to the territory of Assyria.

This text sounds unusual at first—why would towns in Syria, north of the kingdom of Israel, be allied with Judah’s King Uzziah–Azariah? Yet this squares with the biblical record for this period. 2 Kings 14:28 (kjv) reads: “Now the rest of the acts of Jeroboam, and all that he did, and his might, how he recovered Damascus, and Hamath, which belonged to Judah, for Israel ….” Remember the intense civil wars that took place between Judah and Israel during the reign of Uzziah’s father. This continued on into the reign of Jeroboam, who recaptured Judahite-claimed cities within Syria. This may have happened midway through Uzziah’s reign. Tiglath-Pileser iii was on the scene around the end of Uzziah’s reign (2 Kings 15). Apparently, at this point, the allegiance of certain Syrian towns still lay with Uzziah’s Judah. And there is a strong reason why this would be the case.

Toward the end of Uzziah’s life, the northern kingdom of Israel was in upheaval, with assassinations and usurpations. Jeroboam’s son Zechariah only lasted six months before being murdered and replaced by Shallum, who in turn only lasted one month on the throne before being murdered and replaced by Menahem. Menahem, though, faced resistance from his own people to his reign, from Tiphsah (probably within Syria) as well as the central Israelite town of Tirzah. As a result, Menahem turned on those cities who “opened not up to him” and destroyed them; incredulously, “all the women therein that were with child he ripped up” (2 Kings 15:16).

This violent civil war would explain why, as Tiglath-Pileser iii began his reign and conquests, he noticed several Syrian towns had allied themselves with Azariah. There is even a Syrian enclave noted in eighth-century Assyrian annals that is spelled in the same Assyrian form as “Judah”—it seems this northern alliance had even taken up the name of the Jewish nation, showing their rejection of Israelite rule.

2 Kings 15 continues to describe Tiglath-Pileser’s ongoing campaign into Israel against Menahem, who paid off the Assyrian king.

(There has, of course, been dissent among certain scholars about the identity of this “Azrijâu mât Jaudaai” in Tiglath-Pileser’s inscriptions. The weight of evidence, though, points to it being King Azariah–Uzziah of Judah. More information about this can be found here.)

And As for His Bones …

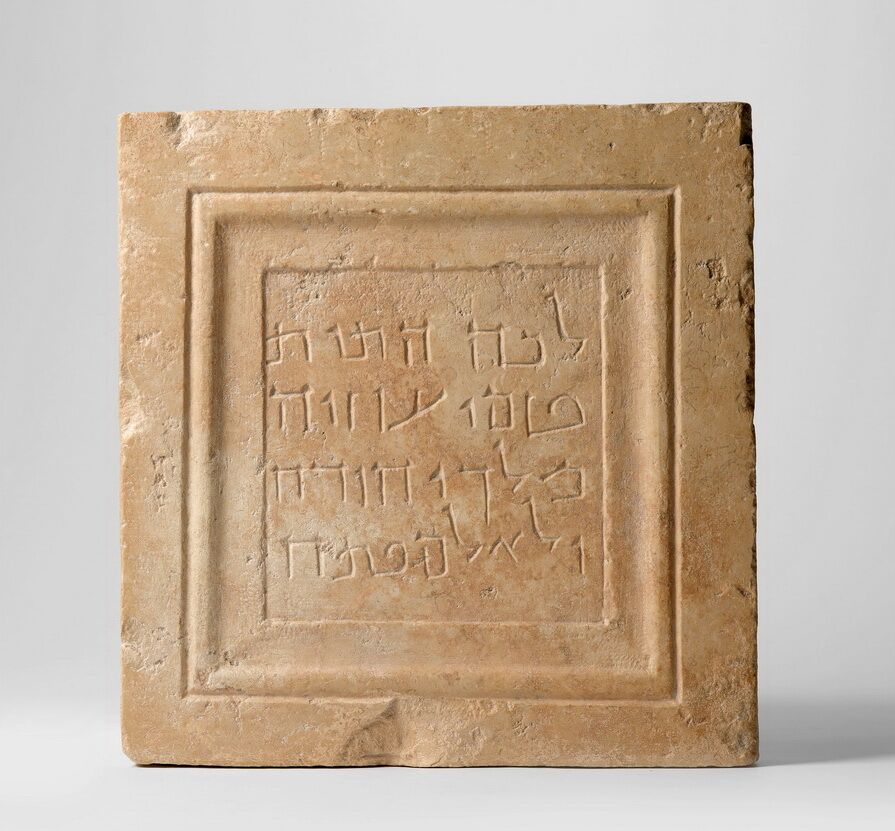

No, the bones of this king have not been found. But a gravestone has been found, known as the “Uzziah Tablet.” This tablet was noticed in the 1930s as part of a Mount of Olives collection in a Russian convent. The engraved stone is written in Aramaic script, dating to the first century c.e. The text reads:

Here were brought the bones of Uzziah, king of Judah. Not to be opened.

It appears that this plaque was intended to commemorate a reburial of the king. This likely had to do with Jerusalem’s expansion during the Second Temple period—the tomb, which was already separated in a field (due to Uzziah’s leprosy), needing to be moved to a new location outside the city. Hence, the new reburial plaque. Or, perhaps, Uzziah’s grave was exposed and defiled during King Herod’s grave-robbing, or the field reused for some other purpose and thus the bones had to be moved and reburied. Two hundred years after this purported “reburial” of Uzziah, however, the Tosefta (third century c.e.) assures us that those buried in the chief kingly sepulchres of the house of David remain unmoved and untouched (Neziqin, Baba Batra 1:11).

Archaeology of Kings

The discovery of numerous artifacts such as these is continually shedding light on the biblical kingly history—and they have only validated the biblical account. Nothing has been found to prove the biblical account wrong. The sum total of evidence for the biblical kings is surprisingly immense. The following are kings of Judah and Israel whose existence has been proved conclusively through archaeology (taken from Lawrence Mykytiuk’s stringent analysis in 53 People in the Bible Confirmed Archaeologically):

Kings of Judah: David, Uzziah, Ahaz, Hezekiah, Manasseh, Jehoiachin

Kings of Israel: Omri, Ahab, Jehu, Joash, Jeroboam ii, Menahem, Pekah, Hoshea

Add to that nine other biblically named high-ranking Israelite and Judahite officials, and 25 other biblically named kings of foreign powers that have now been proved to exist through archaeology. And then their officials as well. And the cities they governed. The evidence is remarkable.