The Sephardic Connection

“In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” So went a little saying I learned as a child—conveniently rhyming in English so as to sear the date into memory. But 1492 was also a monumental year for Jews in Spain. In short, an edict issued by the Catholic-dominated government required the expulsion of tens of thousands of Jews from the territory. (New dna evidence suggesting Columbus was of Jewish descent makes the year of his departure less of a coincidence.)

The Jewish connection to the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal) is well documented. The Jews there, also referred to as “Sephardic,” have a long history with the region.

Just how ancient this Jewish link to Spain is, is often relegated to “Jewish tradition.” But archaeology gives remarkable clues, further harmonizing with the biblical record. This harmony contains overtones that take us even beyond the western coasts of Spain.

A Reliable Record

Let’s consider first what is documented in the scriptural account.

By the mid-first century c.e., the link between the Holy Land and Spain is well established.

The Apostle Paul, a famous Jewish figure from the Christian Bible, told his Roman congregations of his intentions to visit them, stopping by on the way to Spain (Romans 15:24, 28). Saying, I’ll visit you on my way to this other, farther-away place, assigns a certain significance to that more distant place.

But even more is contained in the Hebrew Bible that shows a powerful link between these two regions. Reviewing these references before we consider the archaeology gives these artifacts the dramatic attention they deserve.

Though the word “Spain” appears twice in Paul’s epistles to the Romans (spania in Greek), its Hebrew equivalent only occurs in the book of Obadiah (Obadiah 1:20). It is transliterated Sepharad and is the undisputed origin of the “sephardic” designation. But this region is referred to in numerous other biblical passages under a different name.

Of Tarshish and Tyre

The Bible describes some extensive trade networks going both east and west from the Holy Land.

The major eastward port was found near modern-day Eilat—at “Ezion-geber, which is beside Eloth, on the shore of the Red Sea, in the land of Edom” (1 Kings 9:26). The context here is Solomon’s eastern trading networks—particularly involving a place called Ophir (verse 28; also 2 Chronicles 8:17-18; 1 Kings 22:49). This place, and its famous gold, was known in the time of Job (Job 22:24), King David (Psalm 45:10), and has been confirmed by archaeology (see “Proof of the Mystical ‘Gold of Ophir’ Discovered”).

When this port is mentioned in the reign of Jehoshaphat, its ships are referred to as the “ships of Tarshish” (1 Kings 22:49). 2 Chronicles 20:36-37 mention them going to Tarshish. These eastbound “ships of Tarshish” were probably how Solomon acquired his ivory, apes, peacocks and other precious resources (1 Kings 10:22; 2 Chronicles 9:10, 21).

There are far more references to a “Tarshish” in the west. The Bible mentions the launching points for this route: the Phoenician trading center of Tyre, located on the Mediterranean coast in northern Israel, and an Israelite port city south of that in Joppa. As there was no Suez Canal yet, ships sailing from these ports unequivocally went west through the Mediterranean Sea.

A well-known mention of this shipping path opens the famous Jonah account (early eighth century b.c.e.). When called to take a divine warning to Nineveh, Jonah “rose up to flee unto Tarshish from the presence of the Lord; and he went down to Joppa, and found a ship going to Tarshish; so he paid the fare thereof, and went down into it, to go with them unto Tarshish, from the presence of the Lord” (Jonah 1:3). Jonah’s destination is emphasized three times in Jonah 1:3, plus a restatement later (Jonah 4:2). The narrative suggests regular traffic was going to a well-known “Tarshish” to the west at this time (in the opposite direction of Nineveh, which was to the east).

Every indication from history and archaeology pegs this “Tarshish” as modern-day Spain. It was there, particularly in the southwest of this Iberian Peninsula, that a civilization developed that was known to historians like Herodotus (fifth century b.c.e.) as “Tartessos.” Its major trading center was beyond the “Pillars of Hercules” (i.e. Strait of Gibraltar) on the southern Atlantic side of the peninsula at the Gulf of Cadiz.

The region was known for being plenteous in wealth, particularly silver. In the sixth century b.c.e, Jeremiah credited Tarshish for Judah’s silver supply (Jeremiah 10:9).

Our magazine published an interview with marine archaeologist Sean Kingsley about this on May 20, 2022 (“Evidence of King Solomon Found—in Spain! An Interview With Sean Kingsley”). We later published his article on this topic in our 2024 Exhibit Issue. Kingsley quotes Diodorus of Sicily, who linked Solomon’s Tarshish to Iberia in the Bibliotheca Historica. “The country has the most numerous and excellent silver mines,” Diodorus wrote. “The natives do not know how to use the metal. But the Phoenicians, experts in commerce, would buy this silver in exchange for other small goods. Consequently, taking the silver to Greece, Asia and all other peoples, the Phoenicians made good earnings.”

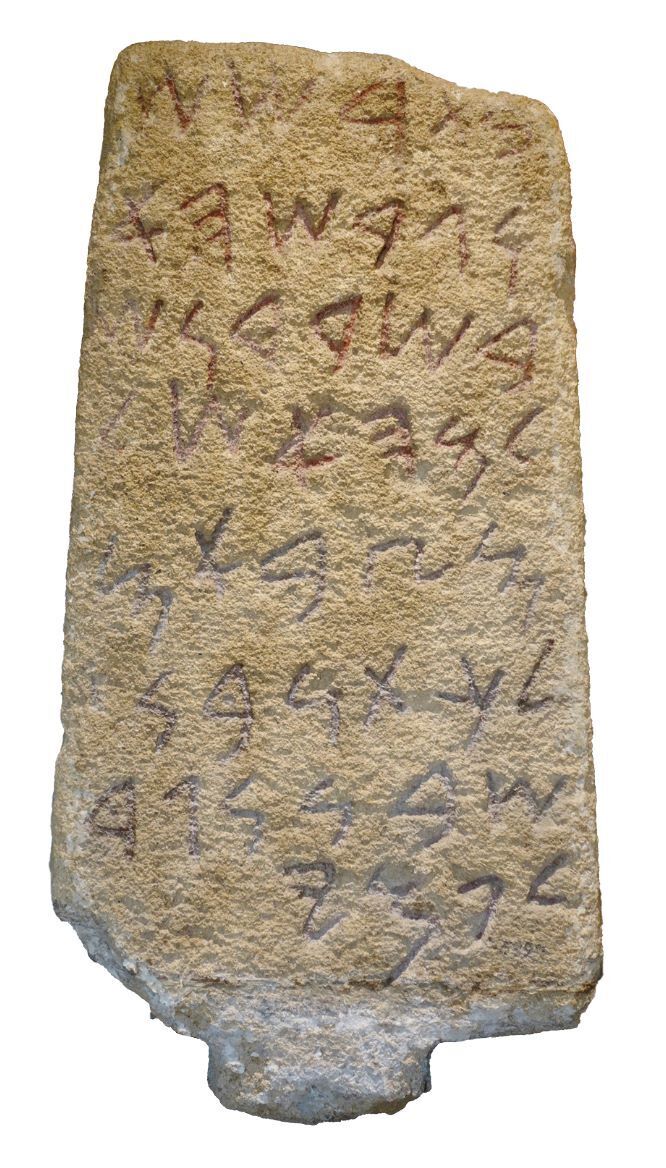

Kingsley also uses an artifact found in the ruins of Nora on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia to prove that “Tarshish was grounded in geographic reality.” The meter-tall limestone inscription contains an eight-line Phoenician dedication commemorating how, as Kingsley wrote, “after defeat in battle, a military force commanded by an officer called Milkûtôn escaped by ship to Sardinia from Tarshish, where his soldiers lived out a peaceful life. Tarshish, then, lay close to Sardinia in the early ninth century b.c.e. when this calling card was committed to stone.”

This was not long after the time of King Solomon, so it is no wonder that his biblical chronicler makes several references to Tarshish. Even his father, King David, referenced the area in Psalm 72.

Anciently an archipelago of three Spanish islands in the gulf of Cadiz were referred to by the mythical name “Hesperides,” or “Esperides,” from the Greek meaning “sunset” (perhaps suggesting a westward direction). The Greek historian Hesiod wrote around 700 b.c.e. that the area was north of Africa’s northwest coast, specifically north of its Atlas Mountains. This Greek word shares an etymological connection to the Hebrew word Obadiah used for Spain: Both share the consonants S-P-R-D.

These isles may be the ones referenced by David when addressing his son Solomon: “The kings of Tarshish and of the isles shall render tribute …” (Psalm 72:10). If not the “Hesperides,” perhaps these western isles are even British? Whatever the case, this shows the king had an intimate knowledge of these far-flung trading posts.

In the time of David and Solomon, it appears that trade to Tarshish went mainly through Tyre (to which the great deal of Phoenician artifacts in Spain from that time period will attest). Tyre would ship goods to Israel by sending items down to its Joppa port (2 Chronicles 2:15), which was still a practice during the second temple’s construction (Ezra 3:7).

Tyre is a key to understanding the Holy Land’s link with ancient Spain. It was “planted in a pleasant place” (Hosea 9:13).

“And Tyre did build herself a stronghold, And heaped up silver as the dust, And fine gold as the mire of the streets” (Zechariah 9:3). This is remarkably similar to a passage about how common silver was in Solomon’s day. Tyre did this by building itself up as a “stronghold.” This is quite the wordplay to the Hebrew ear, since the word for Tyre (tzor) and the word for stronghold (matzor) sound almost identical.

This verse also makes a captivating connection in the materials mentioned: kharutz (rendered “fine gold”) and kesef (silver). In the Bible, silver is usually paired with zahav (gold), but this pairing of silver with kharutz is unique. And it just so happens that two other authors pair them: David does so in Psalm 68:14, and Solomon says these two materials pale in comparison to wisdom (Proverbs 3:14; 8:10, 19; 16:16). Solomon is likely speaking from practical trading experience, and this is yet another somewhat hidden reference to the trading relationship both Israelite kings shared with Tyre.

Tyre’s Hiram, David and Solomon

The Bible makes more overt references to Tyre’s relationship with David and Solomon.

Straddling both their reigns is a king of Tyre named Hiram (2 Chronicles 2:2), who provided cedar and labor to build David’s palace (2 Samuel 5:11; 1 Chronicles 14:1). This trade alliance was probably even more significant when David began gathering materials for his son Solomon to build the temple.

Many of the materials David mentions would have been brokered through Tyre, and much of it came from the west. The biblical record suggests this happened toward the end of David’s life (1 Chronicles 22:5). In verse 14, he says “in my straits [often rendered ‘affliction’] I have prepared …” and then lists specific materials—gold, silver, brass, iron, timber and stone—and their amounts.

There was a time when King David was compelled to retire from battle (2 Samuel 21:17). From this point until his final year of life, there is almost nothing in the Bible’s biography of him. It appears this is when he made his most concentrated effort to gather materials for Solomon’s construction of the temple.

1 Chronicles 29:1-5 give even more specifics about the materials David acquired. Verse 6 shows how the nobles also had much gold, silver, brass and iron themselves to donate to this building fund, indicating a rich market of these materials provided through extensive trade networks beyond their shores.

In verse 2, David mentions silver (likely from Tarshish). Iron wasn’t rare in the region, but “brass” here actually refers to bronze (an alloy of copper and tin, the latter of which would have come from the British Isles through Gibraltar). “This is certainly consistent with the significant archaeological evidence—consistent with the Bible—of the extensive reach of David’s kingdom,” writes Let the Stones Speak editor in chief Gerald Flurry.

In verse 4, David mentions the “gold of Ophir” in this inventory, indicating he would have had some sort of eastern trade going. Perhaps David’s poetic statement of “As far as the east is from the west” (Psalm 103:12) was even rooted in some understanding of how far ships had to go in either direction at the time to acquire these temple materials.

In 1 Chronicles 29, David uses phrases like “prepared with all my might,” “set my affection,” “I have a treasure of mine own of gold and silver … over and above all that I have prepared.” He was personally invested in acquiring these materials. This doesn’t mean he personally traveled abroad to acquire them, but that is not out of the realm of possibility.

Solomon’s portion of the biblical account offers even more vivid details about Israel’s seafaring trade networks. This is also where archaeology begins to corroborate a link between his kingdom and Spain.

Solomon in Spain

A seemingly passing phrase from an elderly, reflective Solomon rings in this context: “I gathered me also silver and gold, and treasure such as kings and the provinces have as their own …” (Ecclesiastes 2:8). The context here is about things he “made,” “acquired” or “got.” But here he “gathered” things—perhaps another nod to massive trade.

His mother’s wisdom, as recorded in Proverbs 31, likened a valiant wife to being like “the merchant-ships” bringing bread “from afar” (verse 14). This is a comparison that would have resonated with the powerful king.

Again, much of this trade would have been facilitated through Hiram’s Tyre (see 1 Kings 5:22, 24-25; 2 Chronicles 2:2-15). Hiram also sent workers, items of “burnished brass” and gold (1 Kings 5:32; 7:45; 9:11, 14; 2 Chronicles 4:11-16).

Hiram’s navy was itself an incomparable resource for Solomon because of its “knowledge of the sea” (1 Kings 9:27). He even sent his men on Solomon’s eastward expeditions (verse 28; 1 Kings 10:11). But the sheer fact that Solomon made silver as common as pavement (verse 27) bespeaks a western trading network—particularly Spain, which was rich in precious metals, gold and especially silver.

Thus we come to the first archaeological discovery to consider: a Solomonic-era mine discovered in Spain. Kingsley discussed this “massive silver extraction village” found near the Roman-period Rio Tinto mine, several miles upriver of the Mediterranean near Huelva. Ironically, this was the city from which Columbus planned his trip in search of Solomon’s gold (as immortalized by a giant statue of him there). The historic mine was still being referred to in the 1600s c.e. as “Cerro Solomon,” or Solomon’s Hill. Kingsley cited Signor A. Carranza who inscribed the mine as such on his map, noting also a landmark named “Solomon’s Castle.”

Kingsley wrote: “The memory of Solomon and ancient mining was alive and well in 1634 when Rodrigo Caro’s Antiguedades y Principado de la Ilustrisima Ciudad de Sevilla described how ‘[t]he inhabitants of those parts have a tradition (so they say) that the people sent there by King Solomon for gold and silver built it [Zalamea la Vieja] and gave it the name Salamea. As proof of this they pointed out that a very old castle that is nearby has been called ever since that time the Old Castle of Solomon.’”

Initial excavations at Huelva unearthed a bevy of Phoenician pottery, ivory and infrastructure to support shipbuilding and silver processing—some of these finds dating to the end of Solomon’s reign.

Kingsley was also involved in the discovery of an ancient anchor around the Israelite port city of Dor (about halfway between Joppa and Tyre). Underneath the 2.5-meter-long, 50-centimeter-thick stone object were wooden beams believed to be part of a ship’s keel. The anchor and the wood were radiocarbon-dated to the 10th century b.c.e., during the reign of King Solomon.

Other Clues From Spain

In addition to the plenteous gold and silver artifacts found in Spain (and on display in its National Archaeological Museum; read “Touring the Bible at Madrid’s National Archaeological Museum” for more information), some stand out for this eastern link with Tyre and Israel in biblical times.

Even in the time of King David, there is evidence of Levantine merchants in Iberia. In a 2008 article, titled “The Chronology of the Late Bronze Age in Western Iberia and the Beginning of the Phoenicians Colonization in the Western Mediterranean,” Mariano Torres Ortiz wrote: “The resuming of trading contacts between the Eastern and the Western Mediterranean begins in the 10th century b.c.e., maybe in the late 11th century. An echo of these contacts could be remembered in the quotations in 1 Kings 10:22 and 2 Chronicles 9:21 referring to the maritime enterprises of King Hiram i of Tyre, maybe in partnership with the Israelite King Solomon. These contacts can be detected in the presence of a Late Bronze Age Atlantic spit and a Ría de Huelva fibula in tomb 523 at Amathus …” that “should be dated at the very latest in the middle or early second half of the 10th century b.c.e.”

Additionally, he mentioned a Cypriot-type bowl at Berzocana that “confirms the Eastern Mediterranean presence in Western Iberia.” (Cyprus’s Kition port also came under Tyrian rule at the beginning of the 10th century b.c.e.)

The decades and centuries following Solomon’s reign are riddled with more objects confirming a link between the Holy Land and Spain.

An ancient site in Cadiz turned up remains dating to just over a century after Solomon’s reign. The site was rich in Phoenician pottery and bones—the dna analysis of which has shown a link to Phoenicia.

Even farther inland, connections have been found linking Spain to Israel. Over 100 stelae found in southwestern Spain depict various warriors with a variety of apparel and accoutrement that are like depictions found on stelae in Galilee, Syria and Turkey. They date to just after Solomon’s reign to about two centuries later.

In addition to trade networks, several other factors may have encouraged actual migration from the Levant into Iberia: a 762 b.c.e. civil war in Tyre, Amos’s earthquake around 760 b.c.e., and two decades of bullying from Assyria, beginning around 740 b.c.e. and culminating in a great Israelite captivity of 721–718 b.c.e.

Given that Phoenicia was rife with polytheism, it is no wonder that some of the most numerous artifacts it provides the Iberian Peninsula are related to pagan worship. This too reconciles with the biblical record.

An alabaster, eighth-century b.c.e. Phoenician-made sculpture of the “Lady of Galera”—found in a late fifth-century b.c.e. tomb near Granada—depicts none other than the goddess Astarte/Ashtoreth (Judges 2:13), known to Solomon as “goddess of the Zidonians” (1 Kings 11:5).

This is on display in Spain’s National Archaeological Museum along with several figurines of Astarte’s consort, the infamous “Baal”—the Canaanites’ thunder god for which Israel had a weakness (Numbers 25:3; Deuteronomy 4:3; 1 Samuel 12:10). This pagan deity was also famous to the Phoenicians as is attested to by one of its darker links with Israel under the infamous Jezebel (1 Kings 16:31).

Another god known in Phoenicia was Melqart, the deity of Tyre—the king of which was considered Melqart incarnate. This harmonizes with Ezekiel 28:1, quoting the king of Tyre as saying, “I am a god, I sit in the seat of God, In the heart of the seas ….”

Melqart’s connection to Spain is fascinating. First, he is depicted on a gold ring found there, dating to the fourth or third centuries b.c.e. But he is also the reason Gibraltar is referred to as the Pillars of Hercules. The exploits of Melqart sound like those of the Greek Hercules: The two are basically identical (much like how the Romans equated Zeus and Jupiter).

Additionally, pagan religious practices noted in the biblical record as being a temptation for Israel are found depicted on the famous Pozo Moro Monument—the centerpiece of Spain’s National Archaeological Museum. This object displays the image of a child sacrifice—a practice repeatedly condemned in the Bible (Deuteronomy 18:9-10). Other images on this monument suggest the fingerprints of a Phoenician artist.

As we get closer to the destruction of Jerusalem in the early sixth century, we come across another interesting find.

A jar buried in a seventh-century b.c.e. Phoenician cemetery was found in Almuñécar, Spain, and is currently on display at Almuñécar’s Municipal Archaeology Museum at the Cave of the Seven Palaces. This jar suggests the Phoenicians were enabling a veritable Antiques Road Show. The jar mentions an Egyptian woman named Ziwat, sister of Pharaoh Apepi (from the mid-16th century b.c.e.), which indicates that the Phoenicians were trading 1,000-year-old vases around the time just before Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon conquered the region.

Slave Trade Profits

This is when Tyre’s trade networks get more interesting. Jerusalem’s destruction around 586 b.c.e. was preceded by two other waves of captivity carried out by Nebuchadnezzar.

During the reign of Judah’s King Zedekiah, Jeremiah had been prophesying that Tyre would not escape Babylon’s yoke (Jeremiah 27:2-11). What this “yoke” meant for Tyre was particularly noteworthy. This is found in the book of Ezekiel, another famous prophet of that time period.

Ezekiel 26:7-11 and Ezekiel 28:7-10 describe Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of mainland Tyre, which occurred around 573 b.c.e., during the reign of Ithobaal iii. But until then, it appears Tyre was profiting off Babylon’s exploits by trading slaves—a commodity that flooded the market as Nebuchadnezzar was conquering the area. Ithobaal iii was known for his wisdom and shrewdness in trade, as described in Ezekiel 28:1-10 as the “prince” of Tyre.

Though many Jewish captives ended up settling into new lives in Babylon (Jeremiah 29:4-7; 52:31-34), the slave trade facilitated the brokering of Jewish exiles to other parts of the world. And Tyre brokered these deals.

Ezekiel had other prophecies for Tyre. Ezekiel 27 describes the power of its trade networks; verses 12 to 13 read: “Tarshish was thy merchant by reason of the multitude of all kind of riches; with silver, iron, tin, and lead, they traded for thy wares. Javan, Tubal, and Meshech, they were thy traffickers; they traded the persons of men and vessels of brass for thy merchandise.”

Tarshish is mentioned, among other locales, in the context of a slave trade: “[T]hey traded the persons of men … for thy merchandise.” Javan, another name for Greece, is also mentioned here. Joel 3:4-6 specifically mention slaves of Judah as being sold by “Tyre and Zidon” to the Grecians. (The Greeks at this time were also colonizing southern France.) Amos 1:9 calls out Tyre for betraying its alliance with Israel to sell many slaves to Edom. Slaves were being dispersed in many directions. Evidence of Tarshish (the region of Spain) being involved goes beyond Ezekiel’s description.

This is where Obadiah’s reference—the only place to use the Hebrew word for “Spain”—sheds more light on the subject: “And the captivity of this host of the children of Israel, That are among the Canaanites, even unto Zarephath, And the captivity of Jerusalem, that is in Sepharad, Shall possess the cities of the South” (Obadiah 1:20).

Until its conquest in 573 b.c.e., Tyre controlled the trading ports in the Gulf of Cadiz and the so-called Hesperides. Obadiah confirms that Jews were sent in that direction. Sepharad is clearly Spain. By the first century c.e., the Romans were calling this region “Hispania,” a Punic or Hebrew phrase meaning “land of rabbits.” But this name seems to have taken hold only after the original Phoenician traders started setting up permanent cities in the Spanish inland.

Obadiah also mentions Zarephath, which is the Hebrew word for France. Again, this is when Greeks were establishing colonies on the Mediterranean coast of France—namely the cities Alalia and Massalia.

Even more fascinating is Obadiah’s choice of words to describe those of the “captivity.” The word usually used for “captivity” in the Bible is shevi and has a connotation of prisoners or those captured in war. This is the word Ezra used to describe those who returned from Babylon decades later (Ezra 2:1; 3:8; 8:35). Lamentations also opts for this word to describe Jerusalem’s fall (Lamentations 1:5, 18). But Obadiah uses the word galut, which sometimes is used in reference to the Babylonian captivity of Jews at this time, but it has more the implication of exile, with a literal meaning of being carried away. This is clearly what Obadiah is describing as he is using terms for faraway trading posts and settlements in the western Mediterranean.

Tyre’s slave trade at this time wouldn’t have benefited Nebuchadnezzar much—with slaves going to the western end of the known world. That is exactly what Ezekiel 29:17-18 describe: Tyre’s destruction ended up profiting Babylon little.

Where Can We Go From Here?

As Kingsley stated: “By exploring the maritime trail beyond the Bible lands and beneath the ocean’s incorruptible waves, the shouts of angry academics fall silent and a rare resource rises—truth.”

The implications from the rich trading network between Israel, Tyre and Spain—of great wealth and even slave transport—raise intriguing questions about Israel’s influence in the ancient world.

One area to consider would be language. After all, these traders had to communicate with one another. Obviously, Phoenicians and Israelites could converse. The marriage of Jezebel (daughter of Phoenicia’s Ithobaal i) to Israel’s Ahab gives us no reason to believe a language barrier existed here. Ithobaal i was also the great-grandfather of Dido, the legendary founder of Carthage. And it is reasonable to assert, at this time, that Hebrew (or at least its Punic, or Phoenician, dialect) was the major trade language in the region.

Furthermore, we should not be surprised to find similarities between the language of the Levant and that of the Iberian Peninsula. It is no wonder that the area of Tartessos (the biblical “Tarshish” of the west) developed a writing system based first on the Hebrew-Phoenician alphabet.

These ancient connections between the Holy Land and Spain also have other captivating ramifications. Trade into the Atlantic Ocean raises questions about just how far these networks ran. The tin wealth of the British Isles likely factored into King David’s stockpiling of temple materials, and perhaps the “isles” David referenced in Psalm 72:10 were in fact British.

A 2012 discovery of tin from a 13th-century b.c.e. shipwreck near Haifa Bay was confirmed in 2019 as being sourced from Cornwall, England (read “Did Israel Source Tin From Britain?” for more information). Logically, by David’s time, this trade route would have been firmly established.

Some evidence would suggest that these trade networks reached Ireland. An Irish Central article dated April 17, 2023, documents a perplexing archaeological find buried in Northern Ireland’s Navan Fort: the skull of a Barbary ape dating between 390 to 20 b.c.e. This species of monkey is unique to North Africa and the island of Gibraltar. One logical explanation given was “the existence of trade routes from the Mediterranean to Ireland.”

Irish history also connects its own land to ancient Spain with an invasion of “Spanish” nobles around the time period of King David, and not long after Tyre had established trading outposts in southwestern Spain. These invaders of Ireland—called “Milesians” (Latin for Spanish soldiers)—per some accounts were a branch of the Jewish tribe of ancient Israel that had settled in Spain for a time.

Looping this region into the language discussion ignites other intriguing connections. In addition to linguistic connections between the Tartessians and Hebrews, there may be the same between the Celts and the Tartessians (and by extension, Hebrew).

Though too detailed a topic to explore here, it is noteworthy that Prof. John T. Koch’s 2009 article “A Case for Tartessian as a Celtic Language” challenges the predominantly accepted theory of Celtic origins—that the language developed in mainland Europe and spread west into Britain alongside iron-working technology. Koch determined the opposite: that the Tartessians likely spoke a Celtic dialect and that Celtic is actually a Bronze Age trade language developed in Spain and the British Isles before spreading east into mainland Europe. The arrival of Hebrew-speaking Phoenicians, or Hebrews themselves, into this part of the world would have enthralling implications for the development of the Celtic language.

Beyond some scant archaeological finds and some new linguistic theorizing, the Holy Land’s Sephardic connection into the British Isles may still lie largely in the realm of speculation for most. But the connection to Spain is beyond dispute. Harmonizing the biblical record with archaeology, the link between the Holy Land and Spain is certain, strong and quite ancient.