The Bible ‘Is Not History’—Because It Doesn’t Cite Sources?

“How do I know—how can I prove to you—that the Bible is not history?” asked a leading academic in a recent interview titled “Archaeologist SHREDS ‘Consensus’ on Torah” on the popular YouTube channel Gnostic Informant. He continued:

Well, when a scholar writes history, when a scholar engages in historical inquiry, and writes an article, or a book, what do you find at the end of that article, at the end of the book, in the last pages? You’ll find a list called a bibliography, right? A list of references. And in the article, in the book, you’ll find footnotes, or endnotes, and anything that the scholar writes, that scholar will have to put a footnote and explain where he or she got his or her information from, right? You have to show where—you can’t just say things—you need to tell your reader where you got your information from. You can’t just say things!

Well, when I look in the Bible, I flip to the back of the book, there’s no list of references. When I look at the bottom of the page in any biblical text, there’s no footnotes. You cannot find, in any Bible, references that explain where the author of the particular biblical text you’re talking about got his information from. He doesn’t give that! Which just goes to show that we’re not talking about history. We’re talking about something very different. We’re talking about stories, and if the word didn’t have such negative connotations, I would use a different word, which I think is a far more powerful word than “stories”: Myth.

To be fair, this scholar emphasized that these sentiments were not intended as a criticism. “I want to make it very clear: I am not, in any way, disparaging stories,” he said. “To the contrary, I think stories are far, far more important and valuable than history. But they are two separate things. … Myths are not the way we use the term today, ‘lies’—they’re not ‘fibs’—myths are stories that are foundational to a culture. And that’s what we’re talking about, when we’re talking about the biblical stories.”

Nevertheless, this allegation that “the Bible is not history”—in the similar words of another leading academic in another interview, that “the Bible does not mean to speak history”—is a common one. But this criticism on the basis of a lack of citation of sources is a particularly interesting objection—because the Bible is replete with them.

‘As It Is Written In …’

Below is a selection of the types of sources cross-referenced in the Bible. Of course, there are hundreds of cross-references between individual books of the Bible; for our purposes here, in emphasizing “outside sources,” we’ll highlight some of the non-canonical texts appealed to in the Bible.

- “[W]herefore it is said in the book of the Wars of the Lord …” (Numbers 21:14)

- “Is not this written in the book of Jasher?” (Joshua 10:13)

- “… are they not written in the book of the acts of Solomon?” (1 Kings 11:41)

- “… behold, they are written in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Israel” (1 Kings 14:19)

- “… are they not written in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Judah?” (1 Kings 14:29)

- “… the account in the chronicles of king David” (1 Chronicles 27:24)

- “… behold, they are written in the words of Samuel the seer, and in the words of Nathan the prophet, and in the words of Gad the seer” (1 Chronicles 29:29)

- “… written in the words of Nathan the prophet, and in the prophecy of Ahijah the Shilonite, and in the visions of Jedo the seer” (2 Chronicles 9:29)

- “… are they not written in the histories of Shemaiah the prophet and of Iddo the seer, after the manner of genealogies?” (2 Chronicles 12:15)

- “… written in the commentary of the prophet Iddo” (2 Chronicles 13:22)

- “… behold, they are written in the words of Jehu the son of Hanani, which is inserted in the book of the kings of Israel” (2 Chronicles 20:34)

- “… behold, they are written in the commentary of the book of the kings” (2 Chronicles 24:27)

- “… behold, they are written among the acts of the kings of Israel” (2 Chronicles 33:18)

- “… behold, they are written in the history of the seers” (2 Chronicles 33:19)

- “… so shalt thou find in the book of the records” of Persia (Ezra 4:15)

- “… it was written in the book of the chronicles” of Persia (Esther 2:23)

- “… are they not written in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Media and Persia?” (Esther 10:2).

Many of the above sources are mentioned multiple times. Excerpts from the Book of Jasher, for example, are actually quoted from in two different biblical passages (Joshua and Samuel). The Book of the Chronicles of the Kings of Israel is cited 18 different times; its counterpart, a Book of the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah, is cited 15 times. There are several additional allusions to more enigmatic “toledoth” works such as the Book of the Generations of Adam (Genesis 5:1) and Book of the Generations of the Heavens and the Earth (Genesis 2:4; Septuagint). Additionally, the Wiseman Hypothesis (otherwise known as the Genesis Tablets Theory) identifies roughly a dozen such “toledoth” book citations within the first 37 chapters of Genesis.

Then there are numerous citations of, and direct quotes from, letters and edicts mentioned in the Bible. The book of Ezra, for example, is virtually one continuous string of citations and lengthy quotations:

- King Cyrus’s edict to rebuild the temple (quoted in part in Ezra 1:2-4; this content parallels the Cyrus Cylinder—Cyrus’s equivalent edict to the Babylonians)

- The Register of Returnees (Ezra 2:1-62)

- The Letter to Artaxerxes from Beyond the River (an official Persian period territorial delineation; letter quoted in Ezra 4:10-16)

- The Response of Artaxerxes (quoted in Ezra 4:17-22)

- The Letter to Darius from Tattenai (quoted in Ezra 5:7-17)

- The Edict of Cyrus (a longer quotation of his initial decree in Ezra 6:2-5)

- The Response of Darius (quoted in Ezra 6:6-12)

- The Letter of Artaxerxes (quoted at length in Ezra 7:12-26).

Numerous other letters, decrees and edicts from foreign and domestic kings are referenced and quoted in other books throughout the Bible.

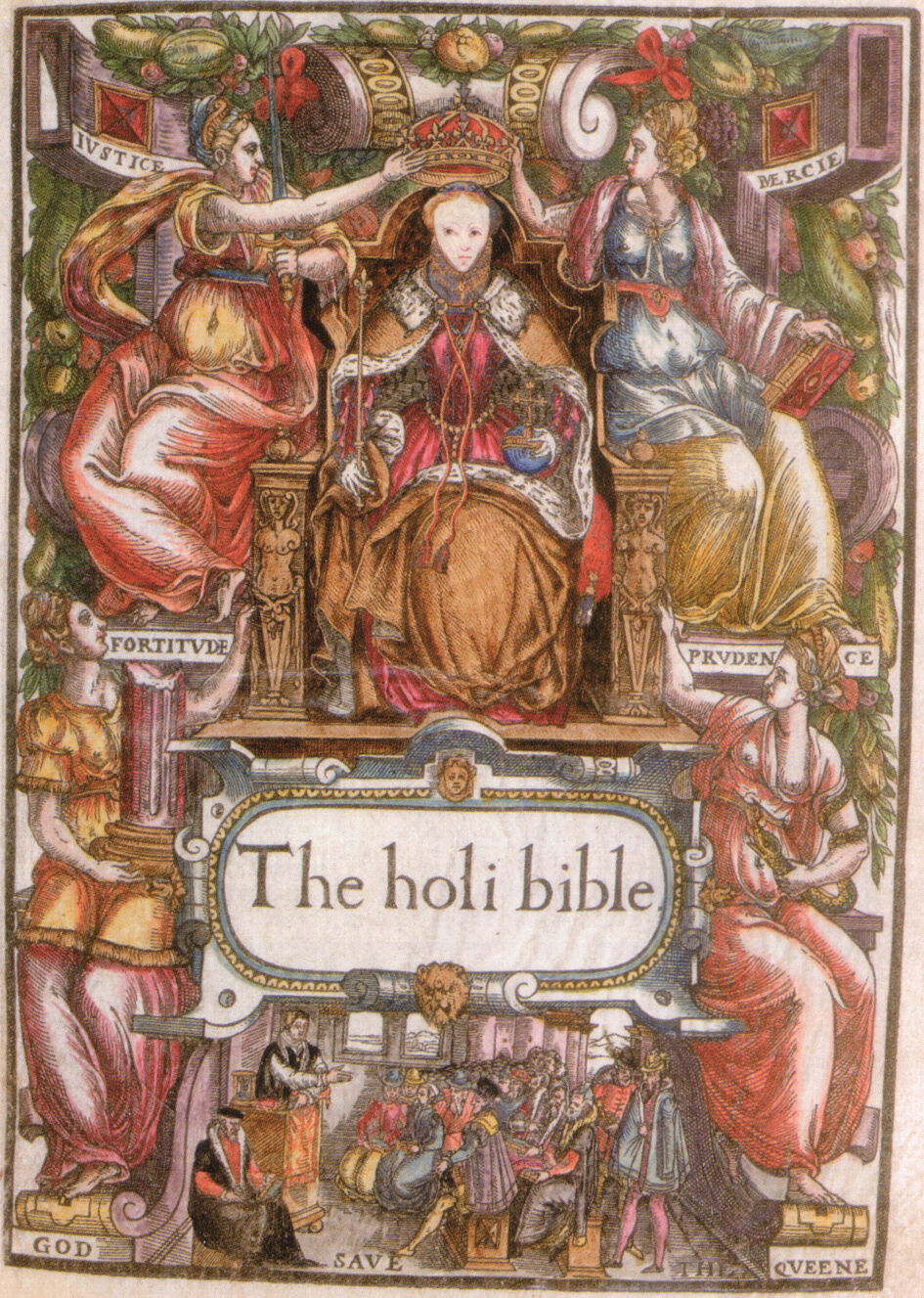

Of course, it would be absurd to expect such references to be included in biblical manuscripts with superscript numerical references and footnotes, as well as a collation of such source material in bibliography form. These are much later conventions. For example, the invention of the footnote is generally credited to the 16th-century English printer Richard Jugge, who first used the feature in his printing of the 1568 Bishop’s Bible.

‘And I Saw …’

It is true that a large body of material in the Bible does not “cite” outside sources as such. But there is a reason for that: In many cases, it purports to relate eyewitness accounts. Material concerning Saul and David, for example, was “written in the words of Samuel,” the contemporary prophet (1 Chronicles 29:29). Material concerning King Uzziah “did Isaiah the prophet, the son of Amoz, write” during the early part of his contemporaneous tenure (2 Chronicles 26:22). “Moses wrote” information contained within the Torah (Deuteronomy 31:9). This type of “eyewitness” testimony is repeatedly cited and prefaced in the books that contain it. Just about every book of the prophets is replete with repetitions of the words “I saw.”

Not to mention the many more references to each of these biblical authors, highlighting precisely the events and reigns of which kings they were contemporary with—allowing the reader to chronologically place them, in some cases, with to-the-day precision. As in the following handful of introductions (with many more, even more specific chronological details throughout the books in question):

- “The vision of Isaiah the son of Amoz, which he saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem, in the days of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah” (Isaiah 1:1)

- “The words of Jeremiah the son of Hilkiah … in the days of Jehoiakim the son of Josiah, king of Judah, unto the end of the eleventh year of Zedekiah” (Jeremiah 1:1, 3)

- “[I]n the thirtieth year, in the fourth month … in the fifth day of the month, which was the fifth year of king Jehoiachin’s captivity, the word of the Lord came expressly unto Ezekiel” (Ezekiel 1:1–3)

- “The word of the Lord that came unto Hosea the son of Beeri, in the days of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah, and in the day of Jeroboam the son of Joah, king of Israel” (Hosea 1:1)

- “The words of Amos … which he saw concerning Israel in the days of Uzziah king of Judah, and in the days of Jeroboam the son of Joash king of Israel, two years before the earthquake” (Amos 1:1)

- “The word of the Lord that came to Micah the Morashtite in the days of Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah, which he saw” (Micah 1:1)

- “The word of the Lord which came unto Zephaniah the son of Cushi … in the days of Josiah the son of Amon, king of Judah” (Zephaniah 1:1)

- “In the second year of Darius the king, in the sixth month, in the first day of the month, came the word of the Lord by Haggai the prophet unto Zerubbabel” (Haggai 1:1)

- “In the eighth month, in the second year of Darius, came the word of the Lord unto Zechariah” (Zechariah 1:1).

The Bible also contains careful strings of transmission and recording of information by manifold contemporary scribes, as well as their overseers; 2 Chronicles 26:11, for example, cites the account “made by Jeiel the scribe and Maaseiah the officer, under the hand of Hananiah, one of the kings’s captains.”

Of course, with all of this information, we now enter the separate, fierce debate among skeptics as to when the biblical books were written—if they really were written as claimed by the eyewitness authors and scribes cited in the timeframes specified, or if they were the imaginings of much later mythicists (“imaginings” that one would have to say are incredibly chronologically specific and for no otherwise obvious reason). But again, as far as our topic here in question goes—in a real sense, we start to see the Bible is one endless stream of “source citation” and chronological anchoring, be it from eyewitnesses authors, or from other, non-canonical texts.

Is it accurate to say, then, that “you cannot find, in any Bible, references that explain where the author of the particular biblical text you’re talking about got his information from”? In light of the above examples, this claim becomes absurd.

And in a real sense, when it comes to the Bible, the book is one endless citation of “where the author got his information from” in a phrase used over 400 times throughout: Thus saith the Lord! This particular “citation,” however, gets into the realm of faith, which is unacceptable for scholarship. Still, the citation is there—it cannot be said that the author did not say from where he got his information.

Is the Bible “history” or “not history” based on whether or not sources are cited? Actually, the question is wrong—this idea of whether or not the “Bible is history” is reductionist in the extreme. The Bible contains history—just as it contains wisdom literature (i.e. Proverbs) and prophecy. The better question, with authorial intent in mind, might be something along the lines of: Do the parts of the Bible that relay past events intend to relay actual history?

If source citations, quotes, chronological anchors and eyewitness testimonies alone are anything to go by, then the answer in the round can only be: Yes.

A Footnote on Historians and Eyewitnesses

The eyewitness account is, of course, of infinitely more worth than the later historian’s account of the same—no matter the number of footnotes, endnotes or the length of bibliography.

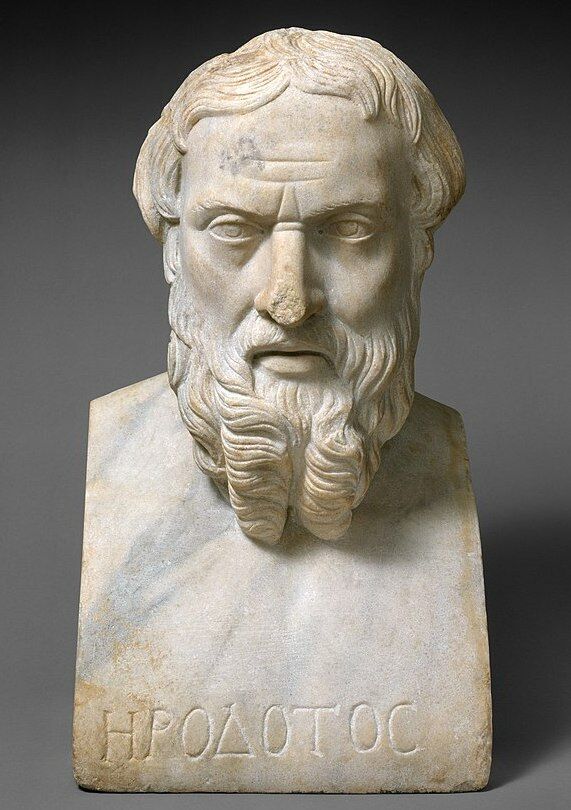

The fifth-century b.c.e. Greek historian Herodotus, famous for his Histories, is often lauded as “first historian” and “father of history.” He did not come without his numerous detractors, however—detractors who have continued, right up to the present day, to brand certain of his “historical” texts as having, ironically, “all the literary earmarks of a novella based on oral tradition rather than an eyewitness account,” as well as including “demonstrably false source-citations.”

One such early detractor was the famous first-century Jewish historian Josephus, who proffered the following not-so-subtle dig, comparing the biblical works with Herodotus’s own (Against Apion 1.26):

For it is no new thing for our captives, many of them in number, and frequently in time, to be seen to endure racks and deaths of all kinds upon the theaters, that they may not be obliged to say one word against our laws and the records that contain them; whereas there are none at all among the Greeks who would undergo the least harm on that account, no, nor in case all the writings that are among them were to be destroyed …. [S]ome [such] persons have written histories, and published them, without having been in the places concerned, or having been near them when the actions were done; but these men put a few things together by hearsay, and insolently abuse the world, and call these writings by the name of Histories.