The Khirbet Qeiyafa Shrine Model: Insights Into Biblical Architecture

The Bible contains a remarkable amount of detail relating to the construction of Solomon’s temple, palace and administrative buildings. Entire chapters highlight various measurements and layouts of these structures built some 3,000 years ago.

Yet for all the detail documented in the biblical text, there is a lot of confusion and debate about the nature and appearance of these structures. Consider, for example, the various artistic depictions of the first temple, built by King Solomon. No depiction of the temple is ever the same, even though all artists use the same text to develop their reconstruction.

Part of the problem is the many peculiar technical terms used to describe these buildings. Bible translations are at odds on the correct way to render these long-obsolete words. In some instances, certain misunderstandings of the text have even led translators and commentators to assume error, and to retroactively “fix” the biblical text.

Now comes the “that all changed when …” cliché. But as cliché as it might sound, it’s true. As Prof. Yosef Garfinkel and Dr. Madeleine Mumcuoglu write in the foreword to their 2016 book Solomon’s Temple and Palace: New Archaeological Discoveries: “From time to time in archaeological research, a single find is able to illuminate and clarify an entire world. We have had this privilege with the discovery of such a find in our excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa.”

“Each generation attempts to understand the temple and Solomon’s palace according to the information available at the time,” they write. “Our great advantage stems from the fact that we have new and revolutionary data. We are now able to clarify the biblical terms … in the depiction of Solomon’s palace and the temple.”

Treasure of Stone

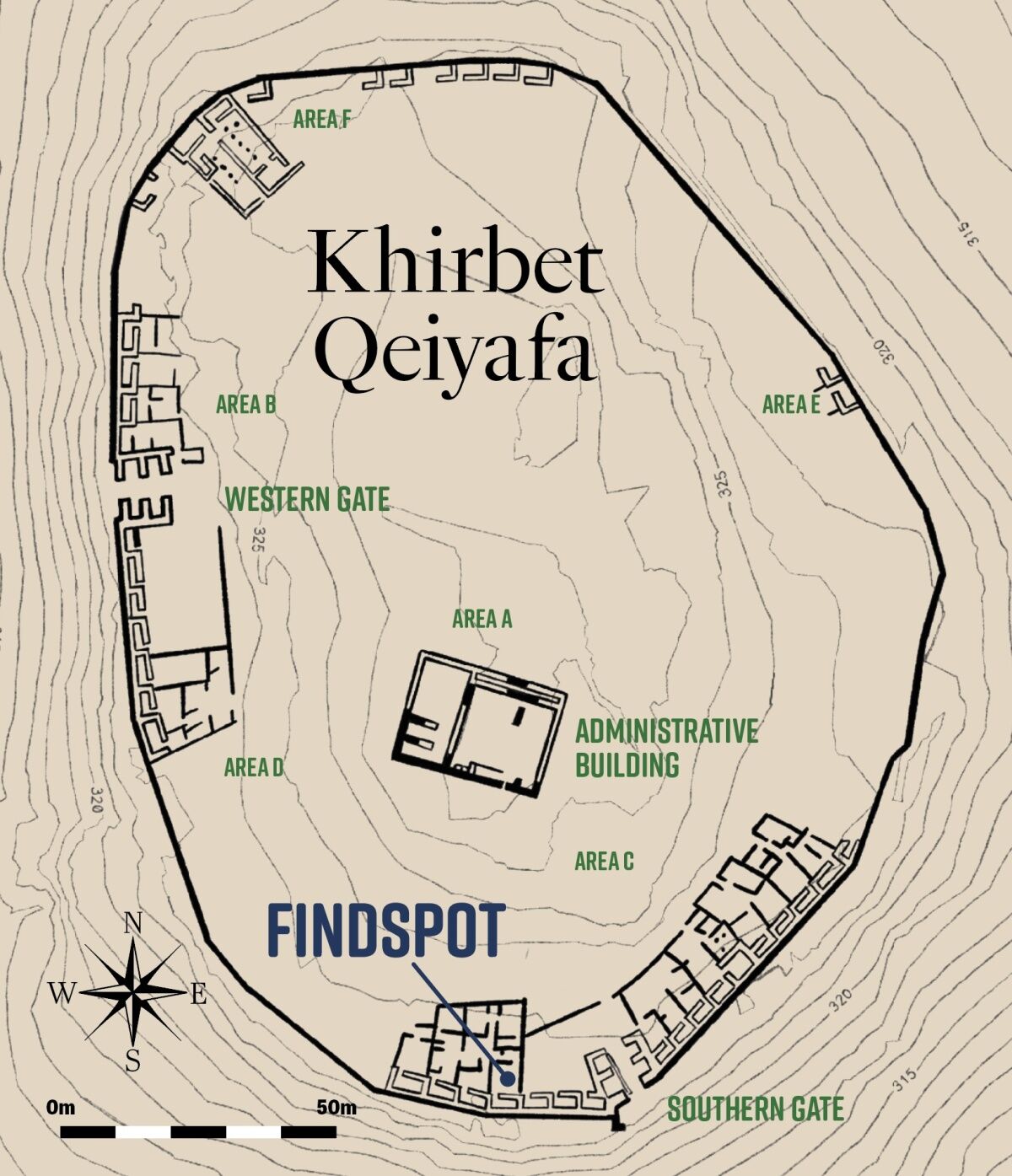

One of the most revolutionary and important sites in the debate about the historicity of the biblical King David is Khirbet Qeiyafa. Situated in the Shephelah (Judean Lowlands), overlooking the Valley of Elah (the place of David’s battle with Goliath), Khirbet Qeiyafa first attracted the attention of Hebrew University professor Yosef Garfinkel and Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist Saar Ganor almost 20 years ago.

In 2007, they initiated a seven-year archaeological excavation. It is hard to overstate the significance of what they have found at Khirbet Qeiyafa and its importance to biblical archaeology: Garfinkel and Ganor discovered a single-period Judean city that was carbon-dated to around 1020–980 b.c.e.—the time period of King David.

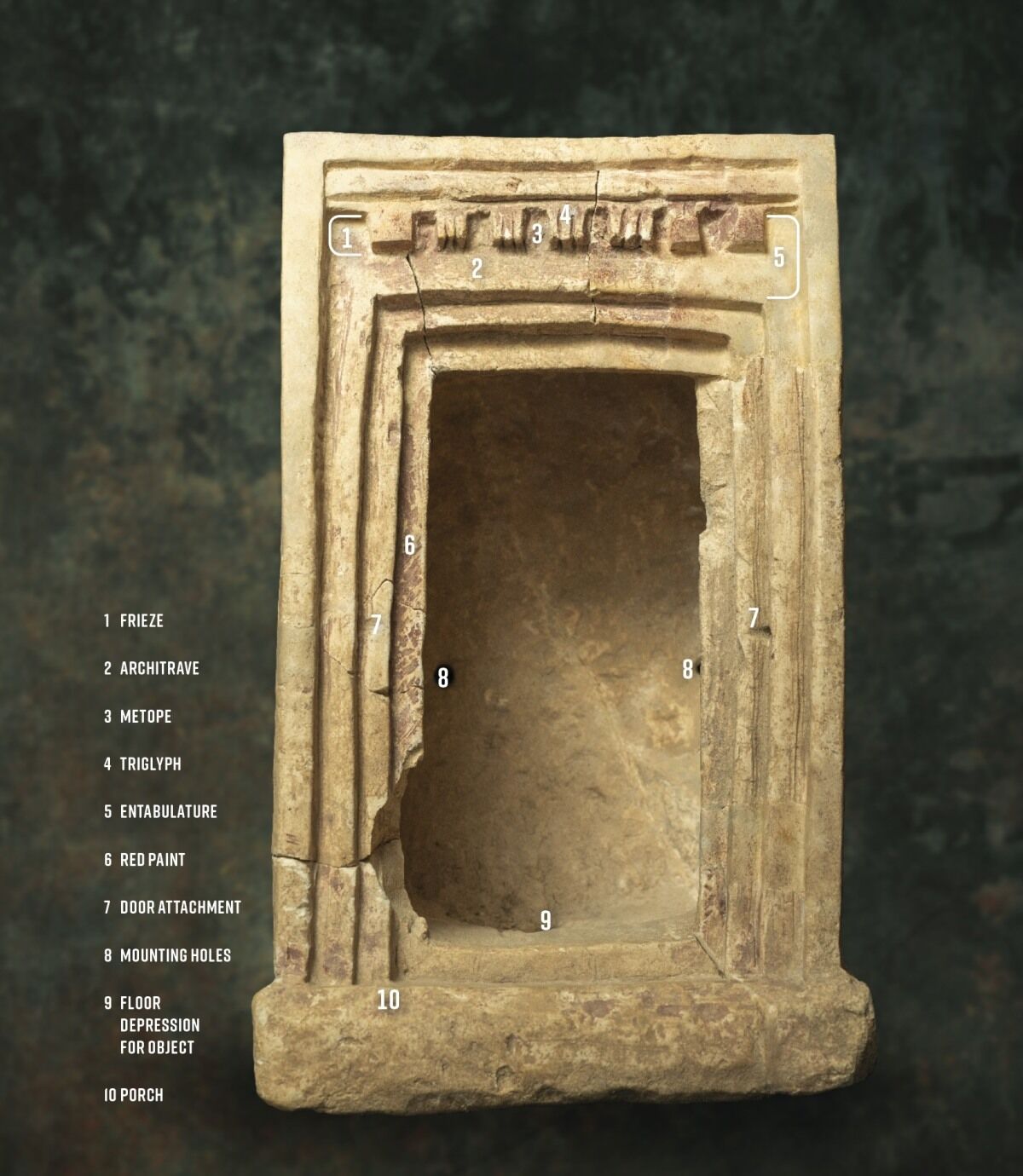

Much has been published on Khirbet Qeiyafa and its broader implications on the discussion about the Davidic kingdom (see here for an overview). Among the many individual discoveries at the site, arguably the most intriguing was unearthed in 2011: a strange box-like, finely carved stone “shrine model.”

The item was found within Room G of Building C10, which is situated near the gate at the southern end of the city. The model, which measures 21 centimeters by 26 centimeters by 35 centimeters, features an open interior, evidently having originally held some item of significance in antiquity. The model’s key feature, however, is its ornate, decorative facade. It very obviously contains a number of sophisticated and intriguing architectural elements.

Most interestingly, these stylistic elements are similar to some of the architectural design features of Solomon’s temple and palace documented in detail in the Bible.

3,000-Year-Old Triglyphs

Carved into the ceiling architrave of the stone box is a row of seven squarish protrusions, each divided into three lines (only the middle four are fully preserved). “It is clear that … these protrusions, although they were made of stone, were meant to imitate [protruding] wood [beams],” write Professor Garfinkel and Dr. Mumcuoglu.

These protrusions are very clearly triglyphs, a known and prominent architectural feature identified by triple-embossed frieze protrusions across the architrave of monumental (often pillared) buildings.

The triglyph is a well-known feature of classical Greek “Doric” architecture, the earliest examples of which emerged in the mid-first millennium b.c.e. It was a feature later used by the Romans and others, and remains a prominent design feature to the present day. “The earliest stone triglyph that we have is dated to circa 600 b.c.e., and there is no direct evidence for earlier examples in other materials except in the temples at Thermon and Calydon, where terracotta metopes were found dated by their style to circa 640 b.c.e.,” M. L. Bowen wrote in 1950, speculating that the design may have originated in Minoan Crete and entered Greece from the south, becoming an established architectural tradition on the mainland (“Some Observations on the Origin of Triglyphs,” Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. 45).

Conversely, early 20th-century expert architect Leicester B. Holland believed that this supposed intrinsically Greek architecture “cannot be considered Minoan in origin, it must have been brought into Greece by the Dorians from the north” (“The Origin of the Doric Entablature,” American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 21, 1917). “The known fixity of form of the Doric entablature in stone from the seventh century b.c.e. for at least four centuries [onward] indicates, therefore, that a period at least equal in length, during which this form was developed structurally and made classic in some other material, must have elapsed before this date … the germs of it [this design feature] at least must have been brought down from the north by the [Dorian] invaders.”

Holland’s postulations on an emergence of this design some four centuries earlier, around the turn of the millennium, could be considered justified. But who could have guessed that the earliest example of such architecture would come, not from southern Crete, nor mainland Greece, nor the northern Dorian territories, but from the Near East—from Israel?

“The triglyph decoration in the temple model from Khirbet Qeiyafa predates the Greek temples several centuries; for example, it predates the Acropolis temples of Athens by about 500 years,” Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu continue. “Our new find revolutionizes the understanding of the development of public construction in biblical times and attests that it began as early as the late 11th to early 10th centuries b.c.e. It also shows that architectural phenomena that developed in the East migrated and influenced Greek Classical architecture. Various scholars have pointed out the strong influences of the ancient Near East on elements of the culture of Classical Athens; we can now add triglyphs as one of these elements.”

That quote is packed with some extraordinary observations, implying that classical Greek and Roman architecture—which humanity has admired for centuries—was influenced by Israelite architecture!

That’s not all. The discovery of the use of triglyphs in Judah some 3,000 years ago proved a eureka moment for Professor Garfinkel and Dr. Mumcuoglu in their study of the biblical text and what it records about King Solomon’s building projects.

Triglyphs in the Bible

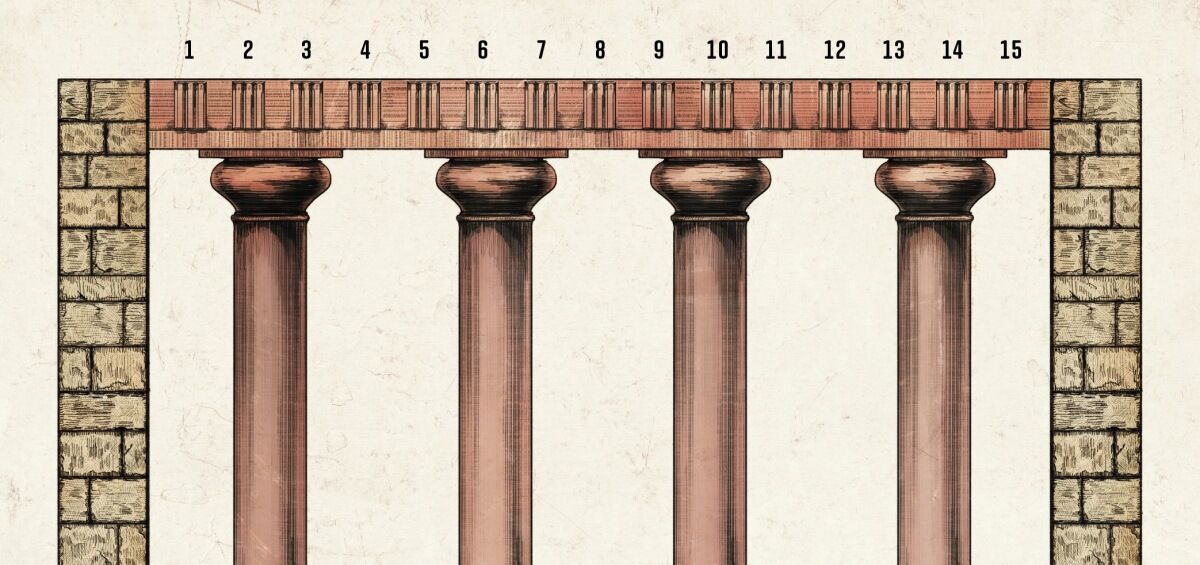

1 Kings 7:2-3 in the King James Version (kjv) read: “He [Solomon] built also the house of the forest of Lebanon; the length thereof was an hundred cubits, and the breadth thereof fifty cubits, and the height thereof thirty cubits, upon four rows of cedar pillars, with cedar beams upon the pillars. And it was covered with cedar above upon the beams, that lay on forty five pillars, fifteen in a row.”

This is a confusing passage. How can you have four rows of 15 cedar pillars totaling 45 pillars? Four rows of 15 pillars makes 60, not 45. And 45 pillars, 15 in a row, would mean three rows, not four.

The exasperation of Bible commentaries in understanding this passage is palpable. “The utter uncertainty as to the number and position of the four rows of pillars is sufficient in itself to render it quite impossible to draw any plan of the building,” concludes the Keil and Delitzsch Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament (1866). The Pulpit Commentary (1899) concurs: “How these [pillars] were disposed of, or what was their number, it is impossible to say … it is impossible to form a correct idea of the building.”

There is so much confusion, some Bible translations have gone so far as to change the figures given in the text. Both the Greek Septuagint and Revised Standard Version, for example, change the “four rows” to read “three” in order to harmonize with the number 45; an early Arabic translation (unnamed, but mentioned by the Pulpit Commentary) changes the total of 45 to 60 in order to harmonize with the four rows of 15.

In their publication, Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu conclude that the House of the Forest of Lebanon does contain four rows of pillars—but that the 15 and 45 do not refer to pillars at all. Rather, these numbers refer to the roof beams sitting atop the pillars. They believe this passage actually refers to 15 sets of beams in groups of three, thus totaling precisely 45 ceiling beams atop the pillars of the structure.

“Based on the Khirbet Qeiyafa stone model, which presents roof beams organized in groups of three like the triglyphs of Classical architecture, we understand the [Hebrew] slaot as roof beams organized in groups of three. Our new interpretation explains the mathematical formula ’45, 15 in each row.’ These numbers relate not to the columns, as believed by most biblical scholars, but to the roof beams.” Thus, the last half of verse 3 is better translated, “the beams that lay on the pillars: 45, 15 in a row.”

The authors cite the biblical description of Ezekiel’s temple as additional support. “The enigma of the ‘ribs’ [slaot] … may perhaps be resolved by comparing … the temple description in Ezekiel 40-43, which includes numerous technical terms, the original meaning of many of which has been lost over time. According to the description, there are 30 groups of three ‘ribs’ around the building (Ezekiel 41:6) ….

The descriptions of the roof in Ezekiel’s temple and Solomon’s palace share the same terminology (‘ribs’/צלעות [slaot]) and the same mathematics (groups of three). Based upon the stone building model from Khirbet Qeiyafa and the description of Solomon’s ‘house of Lebanon,’ it seems to us that Ezekiel described roof beams organized in a triglyph-like arrangement. This would create 30 groups of roof beams with three individual planks in each, yielding 90 planks altogether. (“Triglyphs and Recessed Doorframes on a Building Model From Khirbet Qeiyafa: New Light on Two Technical Terms in the Biblical Descriptions of Solomon’s Palace and Temple,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 63, 2013).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2mCC3MHxig8

Recessed Frames

The most prominent feature of the stone shrine model is the multirecessed doorframe. Recessed doorframes are found commonly in the ancient world, with known parallels going back as far as the Early Bronze Age. Like the triglyph, they are also a feature of grand architecture up to the present day. Multirecessed doorframes are a marker of prestige—the greater the number of recessed frames, the more prestigious the room contained within. (This is explained in detail in Mumcuoglu and Garfinkel’s 2018 book, Crossing the Threshold: Architecture, Iconography and the Sacred Entrance.)

The same concept is related in the biblical text—and again, couched in otherwise-unusual and debated language. 1 Kings 6:31, for example, describes the doorway into the temple’s Holy of Holies. “And for the entering of the oracle he made doors of olive tree: the lintel and side posts were a fifth part of the wall” (kjv). The last three words in the kjv are in italics, meaning they were not in the original Hebrew but were added by the translators in an attempt to make sense of the phrase “a fifth part.”

Verse 33 describes the outer, main entrance to the temple hall: “So also made he for the door of the temple posts of olive tree, a fourth part of the wall” (kjv). Again, the verse ends with the translators’ attempt to make sense of “a fourth part.”

The division of the doorway into fifths and fourths becomes clear in the context of recessed doorframes. Evidently, the main doorway entrance to Solomon’s temple consisted of a quadruple-recessed doorframe; the doorway into the holiest place, or Holy of Holies, a quintuple-recessed doorframe. “The new Khirbet Qeiyafa stone model, coupled with our awareness that recessed doorframes were widespread in temple architecture, gives rise to the interpretation that the Solomonic temple doors were decorated with quadruple- and quintuple-recessed doorframes,” write Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu (ibid).

The same is described of Herod’s temple (also known as the second temple). The Mishnah describes a quintuple-recessed architrave framing the temple entrance (Middoth 3:7).

Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu also point out the triple-recessed frames of the doors and windows on Solomon’s palace—again obscurely translated as follows: “And there were beams in three rows; and light was over against light in three ranks. And all the doors with their posts were square in the frame; and light was over against light in three ranks” (1 Kings 7:4-5). The New Living Translation puts it slightly better: “All the doorways and doorposts had rectangular frames and were arranged in sets of three, facing each other” (verse 5).

Thus we see the gradual increase in doorway-recessions, emphasizing the increasing importance of the structures: triple-recessed doors for Solomon’s palace, a quadruple-recessed entrance to the temple, and a quintuple-recessed entrance to the Holy of Holies.

Door Dimensions

Related to the stone model’s doorframes are the overall dimensions of the door opening itself. They are exact in proportion: The stone model doorway is precisely twice as high as it is wide (20 centimeters by 10 centimeters).

This too is significant. Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu note, “While this may be a coincidence, it is possible that it reflects an architectural concept of entrances to temples and palaces in the ancient Near East” (ibid).

There is no obvious scripture relating the height of Solomon’s temple door in relation to its width. Still, a 2-to-1 ratio is referenced of the porch at the entrance to Solomon’s temple: “And the porch before the temple of the house, twenty cubits was the length thereof … and ten cubits was the breadth thereof before the house” (1 Kings 6:3).

There is, however, the same proportional parallel described of the door of Herod’s temple. The Mishnah states: “The doorway of the porch was forty cubits high and its breadth was twenty cubits”—the same 2-to-1 ratio (Middoth 3:7). Given the deliberate copying of various design elements of Solomon’s temple in Herod’s temple, it is only logical that the doors had the same proportion in Solomon’s.

Seeing Red

One final feature of note: The shrine model, while largely a bare stone surface now, does have traces of having been decorated in some form of iron oxide-derived red paint.

“It seems to have been a common practice in biblical times to paint significant buildings in a striking color, to contrast them with other buildings in the city,” write Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu in Solomon’s Temple and Palace: New Archaeology Discoveries.

They point to the example in Jeremiah 22:14 of King Jehoiakim’s palace, with “spacious chambers … windows … ceiled with cedar, and painted with vermilion,” adding that the Hebrew word “sheshar, translated as vermilion, is mentioned only once in the Bible and its meaning is unclear, but it is usually interpreted as a shade of red.”

For What Purpose?

The Khirbet Qeiyafa shrine model is fascinating for several reasons, including its remarkable and unique design features. The most confounding factor, however, relates to its use: What was the purpose of it?

We can’t be sure. A number of such “shrine models”—otherwise known as “temple models” or “architectural models”—are known from the Bronze and Iron Ages, including examples from sites such as Tell el-Far’ah North (eighth century b.c.e.), Tel Rehov (ninth century b.c.e.), Hazor (Late Bronze Age) and Ashkelon (Middle Bronze Age). There are also several additional unprovenanced examples. There is even another shrine model found at Khirbet Qeiyafa, in the same building (see the sidebar at the end of this article). All of these examples, however, are much cruder in design, and all are molded out of clay.

This Khirbet Qeiyafa model “is unique because to date no other such object made of stone has been found in the land of Israel. Moreover, the design of its facade is not known from any other temple model” (ibid).

It is apparent from the other examples that these models held some sort of religious significance. Their design resembles that of temples, and in some cases, they apparently contained a metal figurine of a deity or some other kind of item of worship. There is a depression on the floor of the Khirbet Qeiyafa stone model, where some sort of object was likely placed. What was it? Was it a figurine? Or some other item of religious significance?

Various ideas have been proposed. Some have compared the shrine model concept to that of the mezuzah—the miniature containers affixed to the doorways of religious Jewish homes, containing passages of sacred Scripture. The back of the stone shrine model contains two holes, perhaps indicating that the box was intended for hanging against a wall.

Similar to the concept of the mezuzah in Judaism are the tefillin (phylactery) boxes, also containing excerpts of Scripture, and on a much grander scale the “arks,” such as those in synagogues, containing the Torah scroll itself. Professor Garfinkel and Dr. Mumcuoglu identify the shrine model as a form of “ark” (Hebrew aron, meaning “chest,” also the term used for the ark of the covenant), an item intended to carry something of religious significance.

Although the why of the shrine models eludes us—for now—the what remains extremely informative. From a time period 3,000 years ago (contemporary with David, Solomon and the construction of the temple and palatial complexes) and from a proximate geographical region (just a day’s walk from Jerusalem), we have a window into what were evidently recognized and utilized architectural features of special prominence. Architectural elements such as the triglyphs, which were used centuries earlier than previously realized, give us a tangible glimpse into what parts of Solomon’s temple and palace would have looked like. And these architectural elements continue to be used to this very day—3,000 years later.

Sidebar: Clay Shrine Model

The stone model was not the only “shrine” item found at Khirbet Qeiyafa. A much more crudely formed clay model was also found in Building C10, the pieces of which were located in two different rooms entirely, having been intentionally smashed in antiquity.

This model, measuring 10 centimeters by 11 centimeters by 15 centimeters, bears some related, yet also very different, motifs. The clay pottery model appears to also depict triglyphs along its ceiling, albeit much more rudimentary and along two tiers. The entrance of this model is framed by twin pillars. Along the top of the model are the fragmentary remains of birds’ feet, belonging to three once prominently displayed birds along the top of the model. At the bottom, adjoining the pillars, are two crouched lion figurines (only the one on the right is intact). The display of two lions together with pillars is especially similar to a Late Bronze Age Canaanite temple at Hazor, excavated by Prof. Yigael Yadin. This temple entrance featured twin pillars fronted by large basalt lion statues.

Prof. Yosef Garfinkel and Dr. Madeleine Mumcuoglu contrast and summarize these two Khirbet Qeiyafa shrine models: “The two models … form a particularly interesting combination. The architectural decoration of the pottery model recalls Late Bronze Age Canaanite temples, while the stone model reflects elaborate structures from the Iron Age. Thus, Khirbet Qeiyafa preserves components predating its period together with elements that were to become typical of the period that followed” (Solomon’s Temple and Palace: New Archaeological Discoveries).