There was a time when biblical minimalists questioned not only the size and nature of King David’s kingdom, but whether David was even a real historical figure. Today, this question has been answered, even to those who consider the Bible an unreliable source of history. An extrabiblical inscription—and likely two more—proves conclusively that King David existed and that he was the patriarch of a royal dynasty.

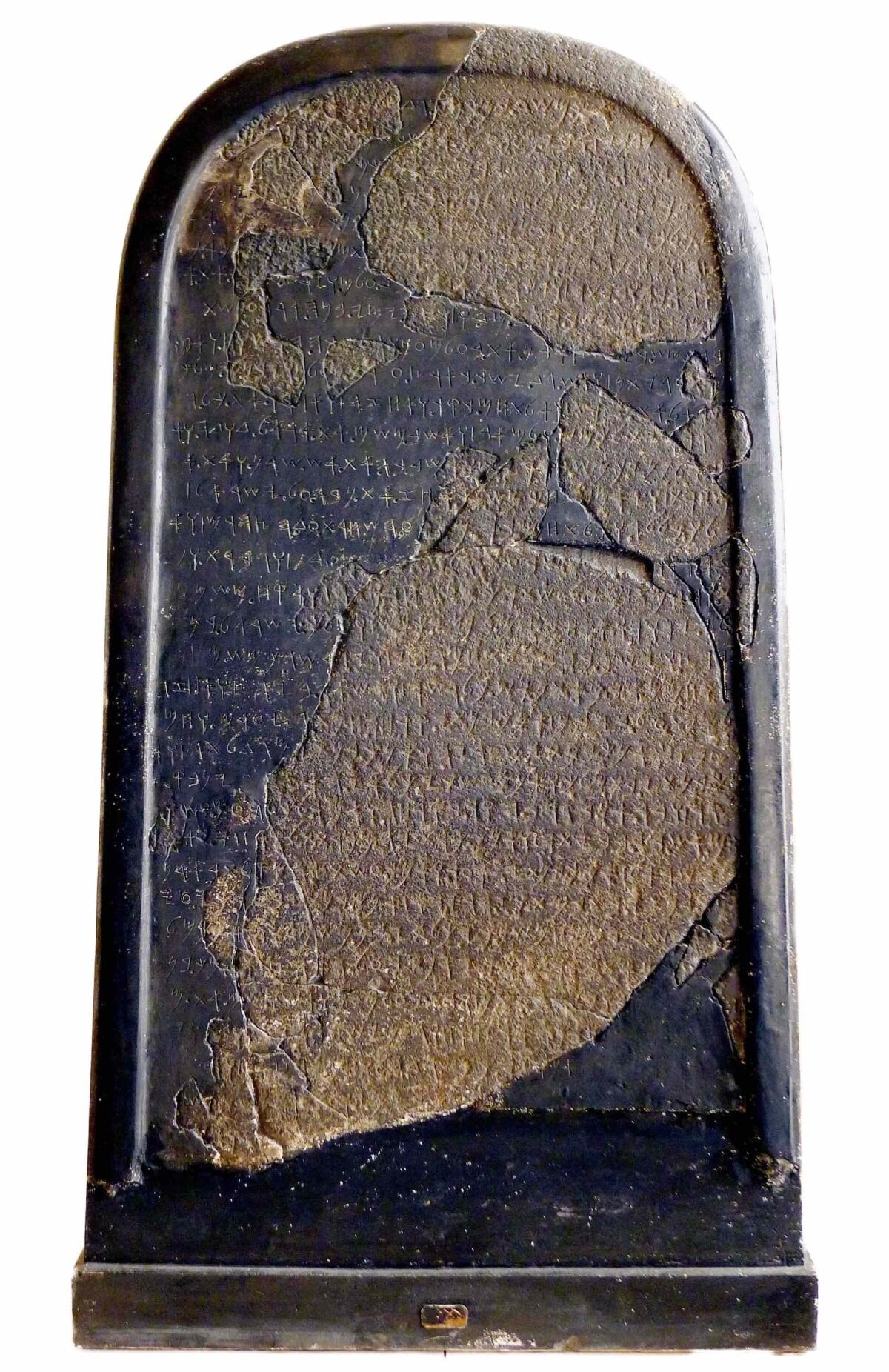

The Tel Dan Stele

Discovered in 1993 by Israeli archaeologist Avraham Biran, the Tel Dan Stele made international headlines and astounded biblical scholars and the archaeological community. The inscription was found during excavations at Tel Dan, an archaeological site in the Upper Galilee situated more than 220 kilometers (136 miles) from Jerusalem.

The text on the Tel Dan Stele records the deaths of kings Jehoram of Israel and Ahaziah of Judah during their battle against the ninth-century b.c.e. Syrian King Hazael. This history, written from the perspective of Israel’s enemy—the Arameans—is recorded in 2 Kings 9.

It is the inscription on the ninth line of the stele that stunned the world. It reads, ביתדוד, or bytdwd, which is translated “House of David.”

The discovery of the Tel Dan Stele marked a milestone in the understanding of biblical Israel. Prior to 1993, no conclusive archaeological evidence mentioning the name of Israel’s most famous king had ever been discovered. The Tel Dan Stele not only confirmed David’s existence, it identified him as the head of a royal dynasty.

Some scholars were skeptical. Initially, only the larger of the three pieces was discovered. The discovery of two more fragments provided additional context. Combining the second fragment with the first, we see a listing of both the kings of Israel and Judah:

קתלת.אית.יהו]רם.בר.[אחאב].מלך.ישראל.וקתל[ת.אית.אחז]יהו.בר.[יהורם.מל]ך.ביתדוד

“… [killed Jeho]ram son of [Ahab] king of Israel and kille[d Ahaz]iah son of [Jehoram kin]g of the House of David ….”

The stele’s credibility was further proved by the presence of a destruction layer firmly dated to the late eighth century b.c.e., which allowed archaeologists to confidently date the Tel Dan Stele (and associated pottery) to the late ninth and early eighth centuries, little more than 100 years after King David died. (When pottery and other artifacts are sealed beneath an ash layer, they can be confidently dated to before the date of destruction.)

The listing of these two kings side by side made clear that bytdwd was a reference to the “House of David,” a Judahite royal title used 26 times in the Hebrew Bible.

The Mesha Stele

The Mesha Stele (or Moabite Inscription) is a victory relief belonging to the ninth-century b.c.e. Moabite King Mesha. The text on the stele pairs with the biblical account recorded in 2 Kings 3.

This formerly complete inscription was found in Jordan by local Bedouin and became known to French archaeologist Charles Clermont-Ganneau in 1868. In 1869, Arab intermediaries were sent to the camp to make a “squeeze,” a papier-mâché, schematic copy of the impression. Not long after the copy was made, the stele was smashed in pieces by the tribespeople and distributed among themselves—probably in order to make money off the separate pieces.

Large chunks have since been acquired and pieced together. The majority of the Mesha Stele was reproduced, thanks largely to Clermont-Ganneau’s “squeeze.” The stele currently sits in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

About 30 percent of the text remains obscure, with the lowest lines difficult to read. In 1992, French scholar André Lemaire proposed the following translation: “[to herd] the small cattle of the land, and Horonen, in it dwelt the house of [D]avid ….”

Translated one year before the Tel Dan discovery, the phrase proved to be similar in form to bytdwd—missing only the initial “d.”

Lemaire’s translation is consistent with the biblical record. The upper section of the stele references the territory of northern Moab; the southern portion, including Horonen (biblical Horonaim), could easily relate to control by Judah, the “House of David.” There even appears to be some connection between Horonen and David’s reign, as related in 2 Samuel 13:34 (note especially the Septuagint version). According to Lemaire, alternative readings of the text are awkward. Still, alternative theories have been put forward.

In 2019, Prof. Israel Finkelstein, Nadav Na’aman and Thomas Römer performed new photo analysis of the Mesha Stele squeeze and claimed that the preserved text could not be confirmed as reading “House of David.” They stated that only the “b” character was clear. They also concluded that space allowed for only three letters, thanks to what they identified as a dividing line in the text—thus proposing the Moabite name “Balak” as perhaps a centuries-old memory of the personality in Numbers 22.

Immediately following their release, a response was given by Associate Professor Michael Langlois, whose own research was about to be published. Langlois spent years poring over the Mesha Stele, utilizing his own new 3-D digital imaging of the artifact. With this technology, Langlois was able to identify a previously unnoticed punctuation mark in the stele, fitting squarely with Lemaire’s original translation. He also noted that there was no evidence for Finkelstein, Na’aman and Römer’s dividing line in the text—dismissing the theory and stating that “the space [for “House of David”] is exactly perfect—no more, and no less.”

Professor Langlois’s latest research confirms with nearly as much certainty as possible that the original proposal, “House of David,” is indeed the correct reading.

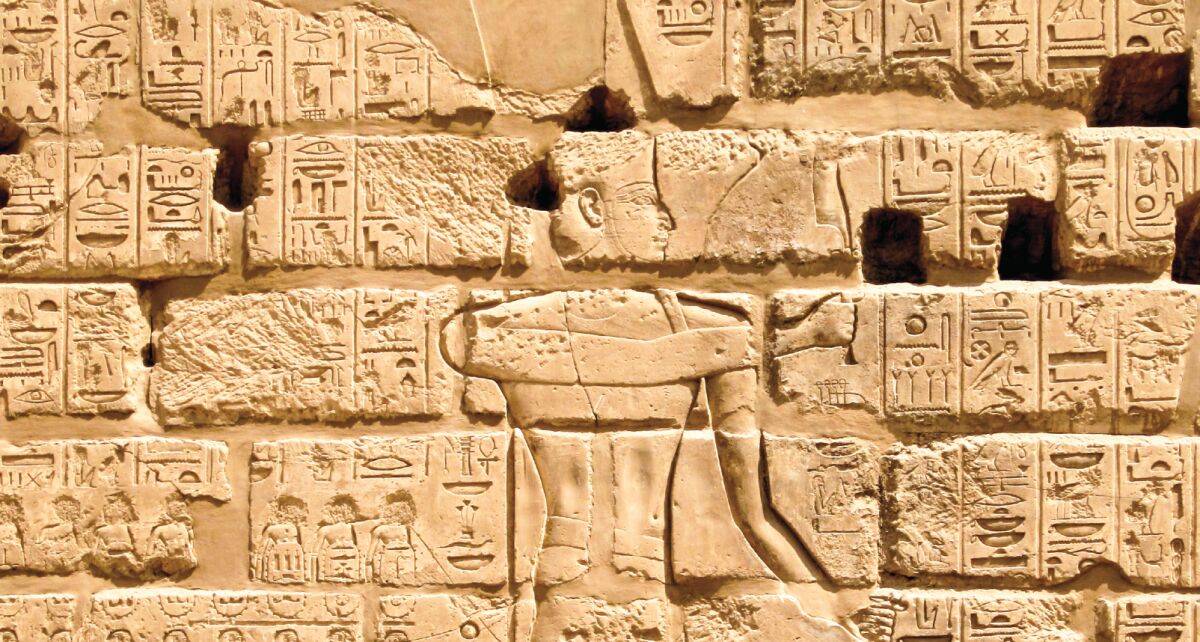

The Karnak Inscription

The Karnak Inscription is an Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription dated to the 10th century b.c.e. The text, inscribed on the walls of the famous Karnak temple in Luxor, Egypt, documents Pharaoh Sheshonq i’s invasion of Israel and Judah. The Bible records this invasion in 1 Kings 14 and 2 Chronicles 12 (where the biblical name Shishak is used).

Many of the names of conquered locations in the southern Levant have eroded or been destroyed. One name, however, apparently relates to a group of areas in the Negev, or southern, region of Judah. The hieroglyphic text is transliterated as: h[y]dbt dwt, and translated by Egyptologist Prof. Kenneth Kitchen as “Heights of David.”

The first Egyptian word indicates heights, or highlands, and fits with the geography of this area of Judah. The second word is more problematic. While the first two letters match the Hebrew dwd for David, the “t” does not.

According to Professor Kitchen, there is no better option. “It could not really be Dothan [probably the closest-spelled alternative]—no final ‘n,’ and in entirely the wrong context for a north Palestinian settlement” (On the Reliability of the Old Testament). Even at face value, the “t” sound in Egyptian hieroglyphs is no great problem—“d” and “t” are similar dental consonants and are readily interchangeable.

As Kitchen notes, the name Davit/Dawit for David from these regions is not unknown. “[I]n an Ethiopic victory inscription of the early sixth century a.d. in southwest Arabia, the emperor of Axum cited explicitly passages from the ‘Psalms of Dawit,’ exactly the consonants dwt as found with Shoshenq” (ibid).

Kitchen cites other examples of the interchangeable Egypt “t/d” during the period. For example, Megiddo and Damascus are both spelled by the Egyptians with a t.

Kitchen summarizes: “This would give us a place-name that commemorated David in the Negev barely 50 years after his death, within living memory of the man. The Negev was an area where David had been prominent in Saul’s time (1 Samuel 24:1; 27; 30).” This would make the Karnak Inscription the earliest reference to this king.