Did Moses Plagiarize Hammurabi?

Displayed inside the United States Capitol building are 23 marble portraits of some of the most influential lawgivers in history. These include figures like Thomas Jefferson, Napoleon Bonaparte, Suleiman the Magnificent, King Edward i, Maimonides and the Prophet Moses. One of the oldest historical figures represented is Hammurabi, king of Babylon.

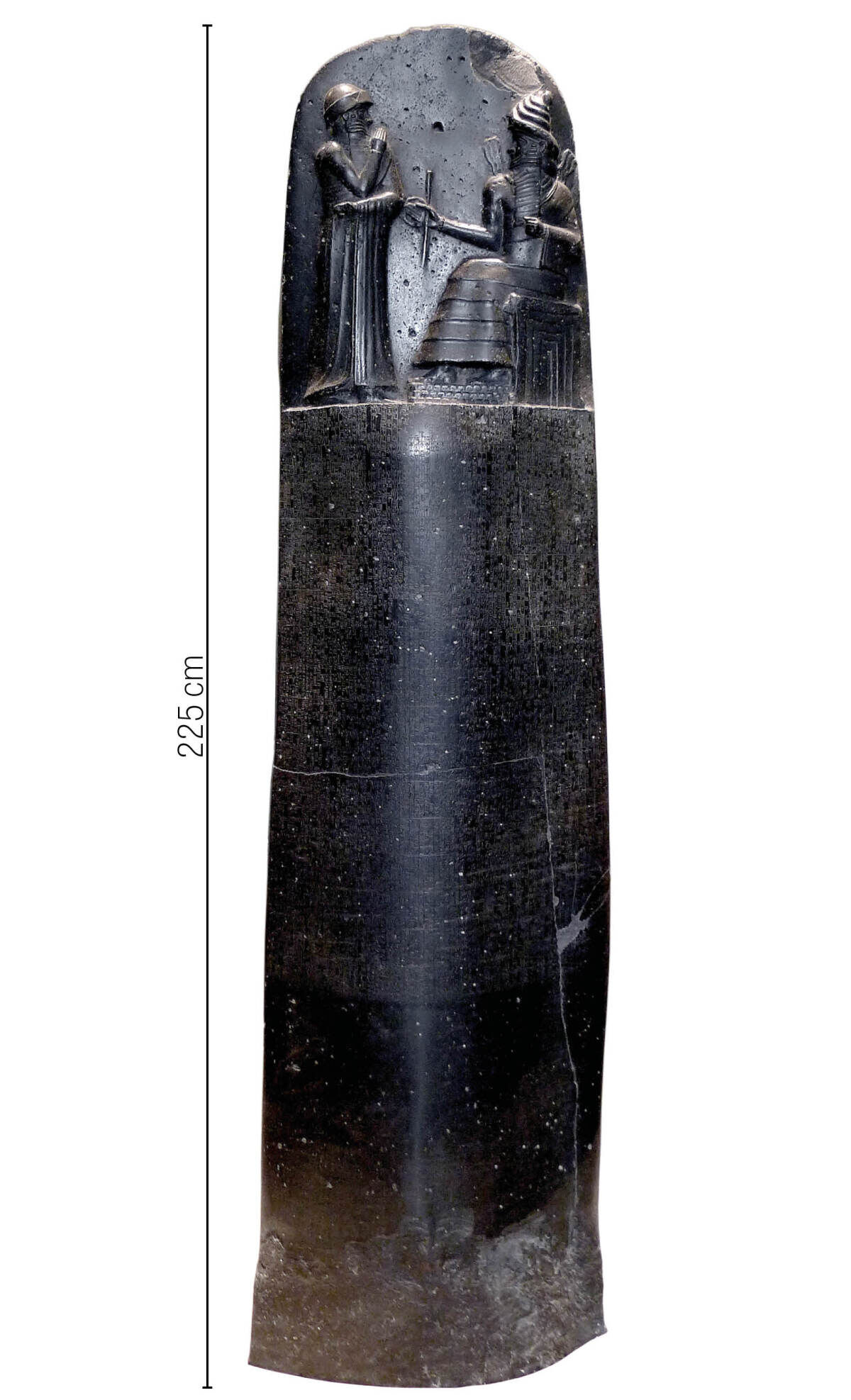

Hammurabi ruled sometime in the 19th to 18th centuries b.c.e. and is famous for authoring a legal text known today as the Code of Hammurabi. The code, which is inscribed on a giant finger-shaped basalt stele, was discovered by French archaeologists in the early 20th century during excavations in Susa, Iran. The office of the Architect of the Capitol calls it “one of the earliest surviving legal codes.”

One of the most remarkable (and most discussed) aspects of Hammurabi’s law code is the striking similarities it has with some of the laws found in the Torah, the first five books of the Bible. Moses, the author (or rather, scribe) of the Torah, lived in the 15th century b.c.e., roughly 300 years after Hammurabi (as evidenced here). The Bible says that Moses received his laws by divine revelation.

Following the discovery of the Babylonian stele, many scholars alleged that Moses plagiarized at least some of his laws from Hammurabi. Such individuals notably included 19th-century German Assyriologist and Old Testament scholar Friedrich Delitzsch, who argued that the Mosaic law was crafted based upon early Babylonian laws. Prof. David Wright similarly argues that the Mosaic law was “directly, primarily, and throughout dependent upon the Laws of Hammurabi … a creative rewriting of Mesopotamian sources” (Inventing God’s Law: How the Covenant Code of the Bible Used and Revised the Laws of Hammurabi).

Naturally, many Bible scholars reject these theories. In the view of Cambridge’s regius professor of Hebrew in the mid-19th century, David Winton Thomas, “There is no ground for assuming any direct borrowing by the Hebrew from the Babylonian. Even where the two sets of laws differ little in the letter, they differ much in the spirit.”

Both sides seem to make a compelling case. Can we know who is right? Was the Mosaic law a direct copy of existing Babylonian laws? Or were these two separate law codes created independently? Is it even possible that Hammurabi was exposed to some of the laws eventually documented by Moses in the Torah?

Code of Hammurabi vs. Mosaic Law

Let’s first examine some of the laws of the Code of Hammurabi and compare them with that of the Bible. Certain laws, naturally, bear more resemblance than others.

A noticeable number of Hammurabi’s laws parallel Exodus 20-23, the passage outlining the Ten Commandments and other statutes. For example, the first law of Hammurabi’s code reads (according to the translation by late English archaeologist Leonard W. King): “If any one ensnare another, putting a ban upon him, but he cannot prove it, then he that ensnared him shall be put to death.” Compare that to Exodus 20:13, which commands us not to “bear false witness.” Similarly, Exodus 23:1 condemns those who give “a false report.”

Hammurabi’s Law 117 says: “If any one fail to meet a claim for debt, and sell himself, his wife, his son and daughter for money or give them away to forced labor: they shall work for three years in the house of the man who bought them, or the proprietor, and in the fourth year they shall be set free.” Compare this with Exodus 21:2: “If thou buy a Hebrew servant, six years he shall serve; and in the seventh he shall go out free for nothing.”

Exodus 21 contains provisions protecting the unborn: “And if men strive together, and hurt a woman with child, so that her fruit depart, and yet no harm follow, he shall be surely fined, according as the woman’s husband shall lay upon him; and he shall pay as the judges determine. But if any harm follow, then thou shalt give life for life” (verses 22-23). Meanwhile, laws 209 and 210 of the Code of Hammurabi say: “If a man strike a free-born woman so that she lose her unborn child, he shall pay 10 shekels for her loss. If the woman die, his daughter shall be put to death.” Hammurabi, in this case, did not treat the unborn child as a person with equal rights. But he did still include legal repercussions for those who harmed the unborn, which are similar to the laws of Exodus.

Many of the laws in the Code of Hammurabi concern the relationships between slaves and their masters. The last law of the Code, Law 282, reads: “If a slave say to his master: ‘You are not my master,’ if they convict him his master shall cut off his ear.” Compare this with Exodus 21:2, 5-6: “If thou buy a Hebrew servant, six years he shall serve; and in the seventh he shall go out free for nothing. … But if the servant shall plainly say: I love my master, my wife, and my children; I will not go out free; then his master shall bring him unto God [or ‘the judges’], and shall bring him to the door, or unto the door-post; and his master shall bore his ear through with an awl; and he shall serve him for ever.” The circumstances that Moses and Hammurabi wrote of were different; Hammurabi was referring to runaway slaves while Moses wrote of slaves who wished to stay with their masters. But the procedure is similar: The slave would be brought to the authorities and then marked in his ear.

There are also parallels with some of the moral laws outlined in the book of Leviticus. Consider Leviticus 18:6-7: “None of you shall approach to any that is near of kin to him, to uncover their nakedness: I am the Lord. The nakedness of thy father, and the nakedness of thy mother, shalt thou not uncover: she is thy mother; thou shalt not uncover her nakedness.” The rest of the passage specifies that all kinds of incest—whether of siblings, stepparents, sons- and daughters-in-law, or any others who are closely related—are abominations to God. Now notice Hammurabi’s laws 154, 155 and 157: “If a man be guilty of incest with his daughter, he shall be driven from the place (exiled). If a man betroth a girl to his son, and his son have intercourse with her, but he (the father) afterward defile her, and be surprised, then he shall be bound and cast into the water (drowned). … If any one be guilty of incest with his mother after his father, both shall be burned.”

It is possible to argue that the laws pointed out above are both similar and dissimilar. Whether or not one set of laws is dependent on the other is still up for debate based on these comparisons.

Perhaps the most famous provision in the Code of Hammurabi, and the most alike to that of the Bible, is the law about an “eye for an eye and tooth for a tooth.” Here are laws 196, 197 and 200: “If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out. If he break another man’s bone, his bone shall be broken. … If a man knock out the teeth of his equal, his teeth shall be knocked out.” Compare this with Exodus 21:23-25: “… thou shalt give life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe.”

Recognizing the similarities between these texts, some Christian scholars attempt to redate Hammurabi, claiming he lived several centuries after Moses and took many of his laws from Moses. Roy Schultz observed this in his work Exploring Ancient History: “Historians conclude that the confusion about the dating of Hammurabi is not important. But the matter takes on great significance when it is realized that historians like to believe that Moses fashioned the Ten Commandments after the famous law code of Hammurabi. This makes it vital to know if Hammurabi lived before or after Moses.”

Was this Babylonian legal text authored before Moses? Does the Code of Hammurabi undermine the divine authenticity of the Mosaic law? Does the reign of Hammurabi need to be radically redated in order to maintain biblical inerrancy? The answer may come as a surprise.

The ‘Mighty Prince’ of Babylon

The Bible clearly records that Moses was not the author of the law. Exodus 20:1, for example, says, “God spoke all these words” when the Ten Commandments are introduced. The law delivered at Mount Sinai, and written down by Moses, existed long before Moses in the 15th century b.c.e.

This raises the question: Does the Bible record God sharing this law prior to Moses?

The book of Genesis records the history of a towering man of God who predated Moses by centuries. God revealed His laws to this man, who according to biblical history, spent much of his life in Babylonia. This individual, of course, was Abraham.

Most people know that Abraham was a leading figure in Canaan. Less well known, however, is the fact that Abraham was also a leading personality in Babylon and had a profound influence on the development of Babylonian civilization. This is documented in both the Bible and secular texts. Moreover, there is evidence that suggests Abraham and Hammurabi were contemporaries.

There are a number of different chronologies for Abraham. But while the precise dates for when Abraham lived vary, there is a general consensus that he lived in the first half of the second millennium b.c.e., around the 19th to 18th centuries. This is a chronological fit with Hammurabi.

It’s also a geopolitical fit. This was the period in which Babylon was ruled by an East Semitic “Amorite” dynasty, of which Hammurabi was the sixth consecutive Amorite ruler. The Bible shows Abraham probably had some contact with this dynasty. Genesis 14:13 records that following his move to Canaan, Abraham was “confederate” with the western Amorites in the region. Ezekiel 16:3 even hints at Abraham being an “Amorite,” not racially, but in regard to his geographic origins.

The laws documented by Moses were known to Abraham. The biblical text shows that many of the laws of the Torah were in place centuries before Moses finally wrote them down. For example, the separation of clean and unclean animals—described in Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14—was in place at the time of Noah (Genesis 6:19-21; 7:1-9). Genesis 2:1-3 show the seventh-day Sabbath was sanctified following the creation of man, more than 2,500 years before the Fourth Commandment was written in Exodus 20.

Genesis 26:5 says, “… Abraham hearkened to My voice, and kept My charge, My commandments, My statutes, and My laws.” Genesis 23:6 identifies Abraham as a “mighty prince” even before he migrated to Canaan. Evidence suggests Abraham understood the law and statutes even when he was living in Babylon.

Now what about secular sources? Do any ancient documents outside of the Bible record Abraham’s influence on Mesopotamian civilization?

Abraham in Babylon—in Secular History

Josephus, the respected first-century c.e. historian, wrote in Antiquities of the Jews (1.7.1): “He [Abraham] was a person of great sagacity, both for understanding all things, and persuading his hearers, and not mistaken in his opinions.” Josephus specifically credited Abraham for teaching Mesopotamia astronomy to point to the Creator of the heavens. If he was a renowned teacher of the physical sciences, surely he also would have taught the Mesopotamians the laws of the God who made the heavens?

The third-century b.c.e. Babylonian historian Berossus wrote: “In the 10th generation after the Flood, there was among the Chaldeans a man righteous and great, and skillful in the celestial science” (emphasis added). While Abraham is not named explicitly here, Josephus commented that Berossus was describing none other than Abraham (who, according to Genesis 11, was on the scene in Chaldea 10 generations after the Flood).

The second-century c.e. Clement of Alexandria cited an ancient hymn about a “certain unique man, an offshoot from far back of the race of the Chaldeans,” who was “knowledgeable” among his population and a man who had a relationship with the mighty God. The first-century b.c.e. historian Nicolaus of Damascus also wrote of Abraham’s prominence before his sojourn in Canaan.

Eusebius, the fourth-century c.e. Roman historian, cited an earlier source by a man named Eupolemus (second century b.c.e.), titled Concerning the Jews of Assyria. Quoting this source, Eusebius wrote that Abraham “surpassed all men in nobility and wisdom, who was also the inventor of astronomy and the Chaldaic art, and pleased God well by his zeal towards religion” (Praeparatio Evangelica, 9.17).

Josephus further recorded that while in Babylon, Abraham “determined to renew and to change the opinion all men happened then to have concerning God; for he was the first that ventured to publish this notion, that there was but one God, the Creator of the universe” (op cit).

Apparently, numerous other texts included a similar refrain, but these have now been lost to history. Josephus wrote that the sixth-century b.c.e. Greek historian Hecataeus not only mentioned Abraham by name, but also composed an entire book about the patriarch’s exploits. (Unfortunately, only two fragmentary works from Hecataeus’s many writings have survived to this day.)

Remember what God said about Abram—that he “hearkened to My voice, and kept My charge, My commandments, My statutes, and My laws”? Consider that alongside the information documented by secular historians that Abraham was a highly educated and influential leader in Babylon. Isn’t it logical to believe that Abraham shared his knowledge of the biblical laws?

It’s possible that those laws could have reached all the way to King Hammurabi of Babylon.

Transformation of ‘Sin City’?

Babylon is synonymous with sin in the Bible. Its founder, Nimrod, built it in direct rebellion against God (Genesis 10:10; 11:1-9). When you study the Code of Hammurabi, however, it reveals a formidable Babylonian state that, at least for a certain period of time, observed laws that appear similar to those credited in the Bible as being divinely inspired.

In Deuteronomy 4, God says that He gave Israel His laws for a specific reason: to point to Him and His limitless wisdom. “Observe therefore and do them [God’s laws]; for this is your wisdom and your understanding in the sight of the peoples, that, when they hear all these statutes, shall say: ‘Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people.’ For what great nation is there, that hath God so nigh unto them, as the Lord our God is whensoever we call upon Him? And what great nation is there, that hath statutes and ordinances so righteous as all this law, which I set before you this day?” (verses 6-8). God wanted Israel’s legal system to be an example to the neighboring nations and to ultimately point these people to Israel’s God.

Genesis 26:5 shows that Abraham kept God’s laws. And the classical accounts tell us that Abraham evidently did not hide his obedience from prying eyes; in fact, he shared his knowledge with the people of Babylon. Though he by no means “converted” the people of Babylon, could it be possible that Abraham’s righteous example actually brought Babylon, of all places, closer to God’s biblical standard? Did he play a role in the composition of the Code of Hammurabi? Again, is it just coincidence that such similar laws appear from the same time period and place as the “mighty prince” and patriarch, Abraham?

One final scripture to this end. The following prophecy given to Abraham foretells the Israelite conquest of certain peoples within Canaan—and that such a conquest would be delayed several generations, on account of one tribe: those same people to which Abraham was “confederate” and to which Hammurabi was associated.

“And He said unto Abram: ‘Know of a surety that thy seed shall be a stranger in a land that is not theirs [Egypt], and shall serve them …. And in the fourth generation they shall come back hither; for the iniquity of the Amorite is not yet full” (Genesis 15:13, 16). This primarily refers to Canaan. But remember that Babylon too, at this time, was governed by an Amorite dynasty (including Hammurabi).

Why was the “iniquity” of the Amorites “not yet full,” as with the other surrounding peoples? Could it be because they were adhering, in some form or other, to a degree of “righteous” laws—to that famous Babylonian Amorite text, the Code of Hammurabi?