Jerusalem’s Most Ancient Fortification

Some of Israel’s most important archaeological discoveries were made by accident. The first Dead Sea Scroll was discovered when a young boy threw stones into a cave in Qumran and heard the sound of broken ceramics. The Ketef Hinnom scrolls, which contain the oldest portion of the Bible, going back 2,700 years, were discovered by a bored teenager pickaxing through what turned out to be a false floor of a tomb. It’s no surprise then, that Jerusalem’s oldest monumental construction also took archaeologists completely by surprise when it was uncovered.

When Haifa University professor Ronny Reich was asked in 1995 to conduct a salvage excavation on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority in the area surrounding the Gihon Spring, he had no expectations of uncovering anything remarkable.

When Reich started digging, the surrounding area was already the most excavated site in Israel. Given the extensive excavations undertaken by archaeologists Charles Warren, Montague Parker and Kathleen Kenyon, Reich thought the preserved remains would be piecemeal and fragmentary. It wasn’t long, however, before Reich and fellow archaeologist Eli Shukron realized, in Reich’s words, that he was “utterly wrong.”

The archaeologists uncovered not only some of the most impressive construction in Jerusalem’s history, it was also the earliest construction ever found in Jerusalem! The ruins dated back 3,800 years, almost 1,000 years before King David controlled the city. The Gihon excavations by Reich and Shukron revolutionized our understanding of ancient Jerusalem! Here is a brief look at what they found.

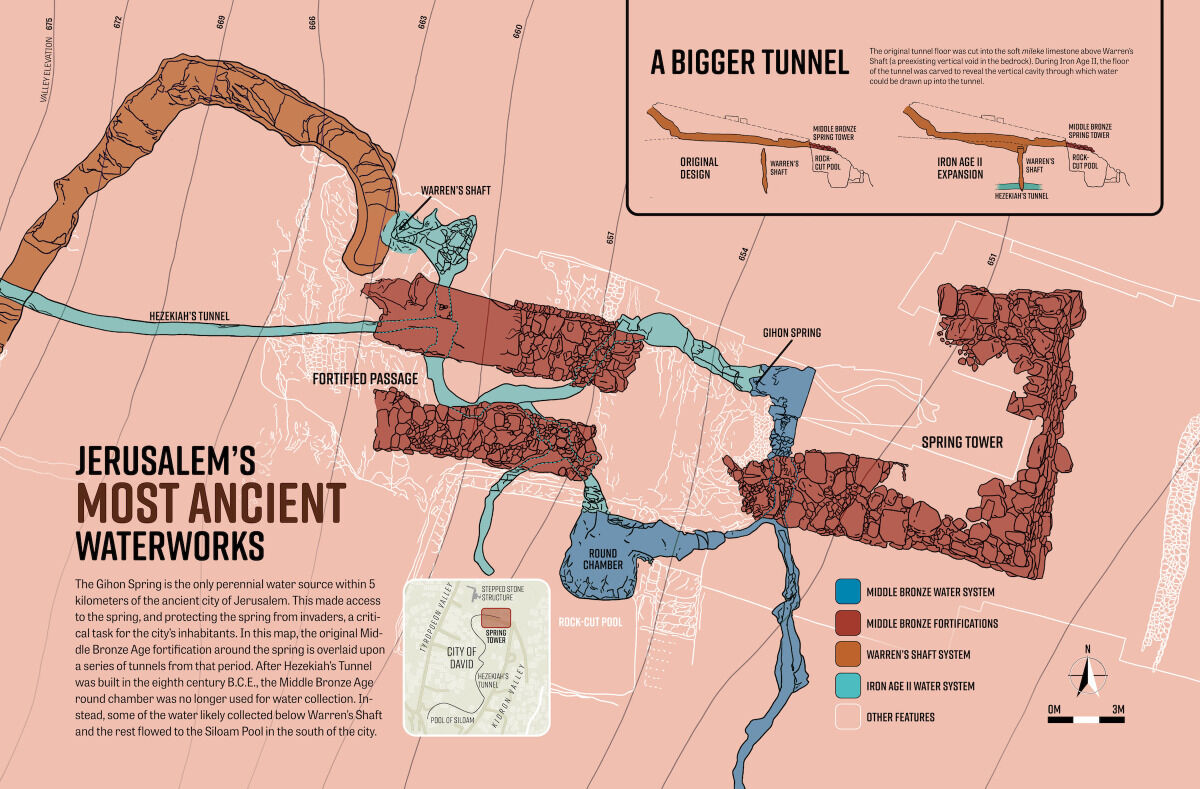

The Spring Tower

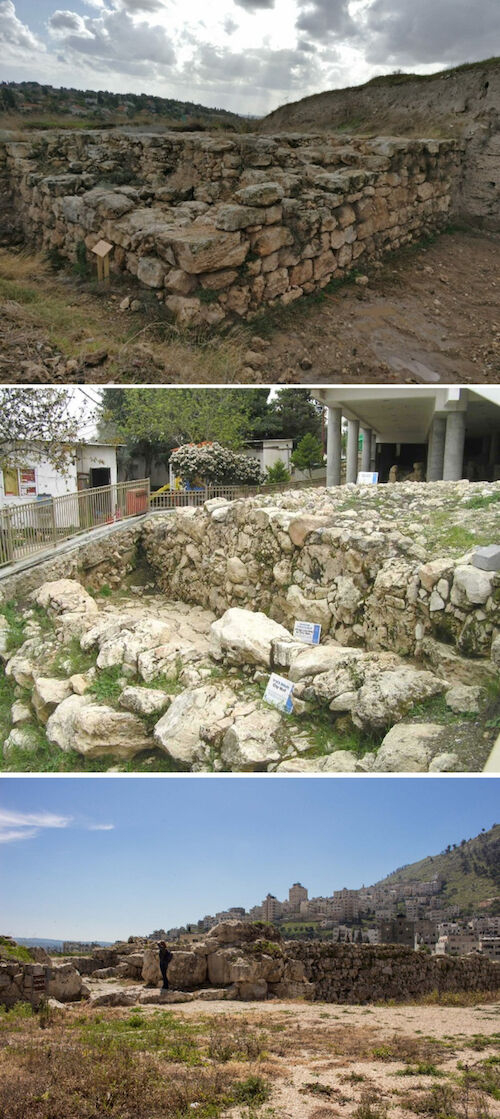

It is a rule of urban development, past and present, that a city’s water source needs to be secure. In most of Israel’s ancient sites, this meant being able to access the water—be it a spring or shaft to groundwater—without having to go outside the city walls. Jerusalem’s only constant water source is the perennial karstic spring known as the Gihon. The exit point for water from the Gihon is near the bottom of the east side of the Eastern Hill (in what is known today as the Kidron Valley).

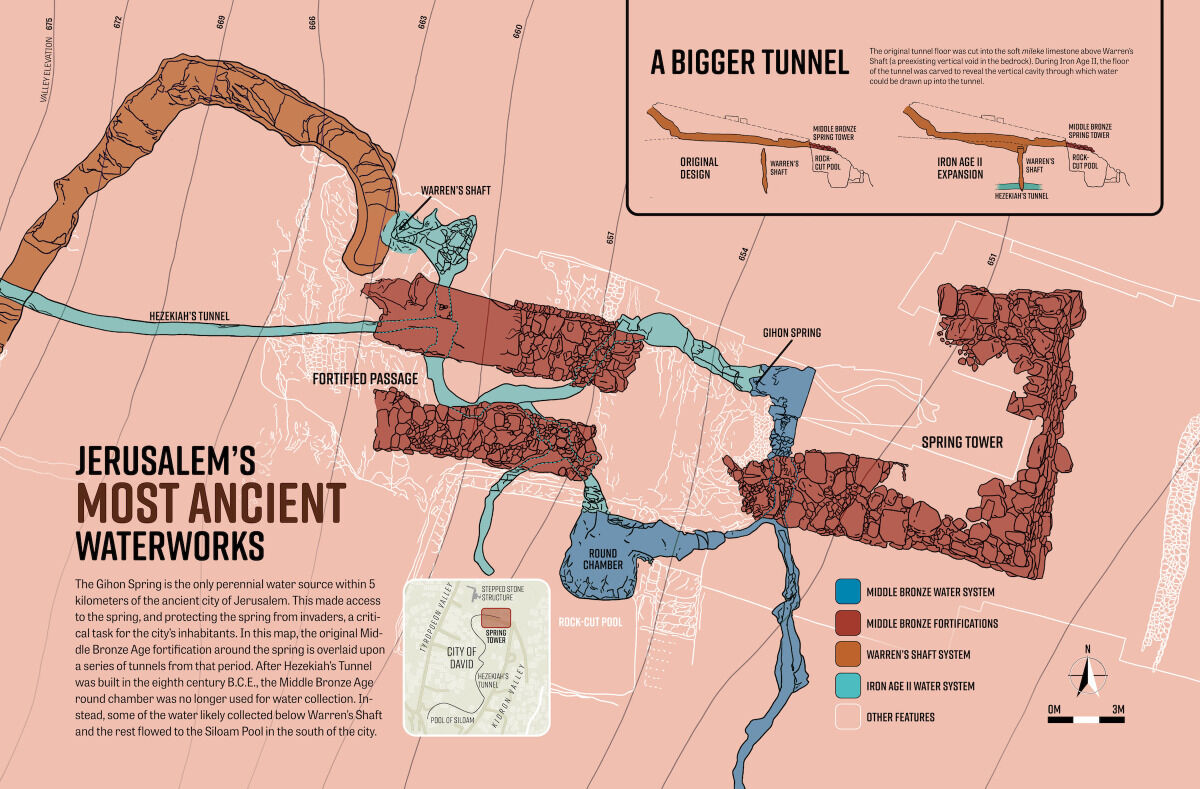

Given this reality, it probably should not have been too much of a surprise when Reich and Shukron uncovered a massive fortification tower encircling the Gihon Spring. After studying both the masonry and pottery, the archaeologists dated the walls to the Middle Bronze Age ii (around 1800 b.c.e.).

The walls on the south, east and north of the structure are massive. The southern wall, for example, is 7 meters thick. The walls are constructed in the cyclopean masonry style. This style of construction was named by the Greeks, who considered the masonry so impressive that it must have been built by the mythical giant cyclopes race. The cyclopean style, in which massive unworked stones are fitted together in a fluid pattern, is typical of the Middle Bronze Age.

Today the area around the Gihon Spring is managed by the City of David Foundation, and tourists are able to access the bottom of the Spring Tower. From here, one can look up and get a sense for the grand scale of the fortification. Some of the largest stones in the wall are estimated to weigh 2 to 3 metric tons. According to Reich, these stones are the largest to appear in a Jerusalem construction until almost 2,000 years later with King Herod’s construction of the Temple Mount.

The Fortified Passageway

In addition to the massive Spring Tower, Reich and Shukron also discovered two parallel walls that intersected with the tower and headed west up the hill. Constructed in the same cyclopean masonry style, these walls are also monumental. The northern wall (Wall 108) is especially large, with a preservation height of 8 meters. Excavators were able to follow these walls for a distance of 24 meters up the hill. While excavating these walls, Reich found a corridor between the two walls that was full of stone fill. After removing the fill, it was clear that it was originally a fortified corridor used by the city’s inhabitants to access the Gihon Spring.

“Undoubtedly,” wrote Reich in 2018, “this fill of earth and stones was intentionally deposited between these walls and postdates their construction” (Ancient Jerusalem Revealed). Critically, the latest pottery sherds found inside the fill in the corridor dated to the Middle Bronze Age ii (1800–1600 b.c.e.). Also in the eastern part of the corridor, Middle Bronze ii pottery was discovered on the original floor. This allowed archaeologists to date the entirety of the two massive walls to the same period as the Spring Tower—that is, to Middle Bronze Age ii.

The Rock-Cut Pool

Finally, Reich and Shukron uncovered one last feature in addition to the Spring Tower and fortified passageway: a large rock-cut pool that ran alongside the southern wall of the corridor. Perhaps significantly, the upper part of this pool was never plastered. According to Reich, this suggests the water level never reached as high as the top of the cutting. However, in the eastern portion of the rock channel, the pool descends even lower, creating what excavators call a “round chamber.” During the Middle Bronze Age and later, water from the Gihon Spring would have collected in this pool.

This chamber is also directly below a break in the southern wall of the fortified corridor. According to excavators, this meant that Jerusalem’s ancient inhabitants could walk down through the fortified corridor then turn to the right, where they would have been able to lower their vessels down into the pool to collect the water.

Today there is no water in the round chamber. According to Reich and Shukron, the pool stopped receiving water from the Gihon Spring in the eighth century b.c.e. when the round chamber and larger rock-cut pool were filled with debris and flattened to make room for the construction of domestic structures.

The logic here is consistent with the biblical text, which records that during the late eighth century b.c.e., King Hezekiah overhauled Jerusalem’s waterworks. Most notably, Hezekiah built a 533-meter-long water tunnel carrying water from the Gihon to the southwestern part of the city (2 Chronicles 32:2-4, 30; 2 Kings 20:20). Hezekiah’s tunnel is lower in elevation than the “round chamber,” which makes it impossible for the ancient pool to collect water. When King Hezekiah was done with his tunnel, the water that would have filled the “round chamber” instead filled the Siloam Pool.

The pool’s construction appears to be mentioned by the Prophet Isaiah in a condemnation of King Hezekiah and the people of Judah for their rebellion against God: “Ye made also a ditch between the two walls for the water of the old pool: but ye have not looked unto the maker thereof, neither had respect unto him that fashioned it long ago” (Isaiah 22:11; King James Version). Isaiah refers to God as the ultimate “maker” of this pool. But through whom did God make it? Given the dating of the pool to the Middle Bronze Age, is it possible that Melchizedek, the mysterious king and priest of Jerusalem, built this original pool which fell out of use when Hezekiah’s tunnel was created?

Warren’s Shaft

It just so happened that when Reich and Shukron started their excavations in the vicinity of the Gihon Spring, the edge of their area came right up next to one of Jerusalem’s most famous underground caverns, known today as Warren’s Shaft. They decided to connect the new excavation area to the underground cavern to ensure ease of passage for tourists to go from the horizontal portion of the shaft system directly to the spring and then continue to the entrance of Hezekiah’s tunnel. This also provided an opportunity for a fresh investigation of the shaft by Reich and Shukron.

Since its discovery in 1867 by Sir Charles Warren, the shaft system has animated biblical scholars with its tantalizing connection to how Jerusalem was conquered by David’s men. Connecting two passages of scripture found in Samuel and Chronicles, scholars considered this to be the underground passage used by Joab to conquer the city around 1000 b.c.e. However, after analyzing the area in their excavations, Reich and Shukron concluded that only the horizontal part of the tunnel was in use during the time of David and was part of the Middle Bronze Age construction. In their view, the vertical portion of the shaft was only connected to the horizontal portion during the eighth century b.c.e. (See infographic, page 18, for a diagram of the entire waterworks.)

According to Reich, the horizontal portion of Warren’s Shaft was built in the Middle Bronze Age and intended to link up with the fortified passageway, providing a way for Salemites to bring water into the upper city from the round chamber of the pool. They base this on a number of factors. First, the horizontal portion of the tunnel was cut directly through softer limestone and sits atop a much harder form of rock. The walls protecting the fortified passageway were also built directly on top of this hard layer of stone. Practically, it also makes sense that there would be no need for two access points to the water right next to each other during the same period.

Second, although the whole tunnel was excavated by Parker, and then Yigal Shiloh in the 1980s, there was still some datable material preserved along the lower portion of the tunnel, right by the entrance of the vertical shaft itself. Critically, among the rock-chip remains from the quarrying of the lower portion near the vertical shaft, they found eighth-century b.c.e. pottery, long after the Middle Bronze Age.

Thus, a new theory arises: Initially, when Hezekiah’s tunnel was created, all the water from the Gihon Spring was diverted to the Siloam Pool in the southwest of the city. Yet it makes sense that the upper part of the city would still need access to the water. Thus, the horizontal portion of the shaft was lowered to access the vertical shaft. Typically, at normal flow through Hezekiah’s Tunnel, the water from the spring would not collect to a sufficient depth at the bottom of the vertical shaft to easily drop and fill a bucket. However, the recent discovery of remains of an eighth-century b.c.e. sluice gate at the southern end of Hezekiah’s Tunnel (see page 22) could certainly raise the water level collecting at the bottom of Warren’s Shaft. Thus, this would make it possible for the upper part of the city to access the Gihon through the Warren’s Shaft system during the eighth century b.c.e.

Sidebar: Is it Really Dated to the Middle Bronze Age?

In 2012, archaeologists excavated the area on the northeast side of the Spring Tower, near the bottom of the Kidron Valley. As part of their work, the team took carbon samples from a cross section of exposed earth that is directly under the northeastern corner of the Spring Tower. After studying the results of the carbon-14 testing, the team redated the entire Spring Tower. The tower, they claimed, was actually built 1,000 years later, around the time of the united monarchy.

In 2018, Reich contested this conclusion. While he accepted the dating of the sample, he explained that the sample was taken from a location that was likely contaminated by later-period material. This is because this area of the tower is in the Kidron Valley riverbed. This meant that the material excavated and sampled under the northeast corner of the tower was likely to have washed into the area during a flood event. “I believe that the data presented … cannot unequivocally guarantee that the samples under discussion were deposited in situ before the Spring Tower was constructed. Obtaining samples for carbon dating from this location was incorrect.”

Furthermore, redating the whole fortification to Iron Age ii ignores the presence of Middle Bronze pottery along the entire 24-meter fortified passageway. And then there’s the cyclopean construction style of the walls of both the Spring Tower and the giant passageway. This style of construction is a trademark of the Middle Bronze Age across Israel, but not Iron Age ii. Similar construction can be found at other Middle Bronze sites such as Tel Rumeida in Hebron, Tel Gezer and Tel Balata (ancient Shechem).

When you weigh all the evidence, it is impossible, to conclusively redate the Spring Tower and giant passageway out of the Middle Bronze Period.