New Research Reveals Egyptian Women Were Tattooed—Paralleling Leviticus 19

“Tattoos on the lower back became popular in the first decade of the 21st century, and gained a reputation for their erotic appeal,” summarizes Wikipedia of the relatively new trend.

Turns out it’s not so “new.” Try more than 3,000 years old—and with an interesting biblical connection to the Israelite Exodus.

Evidence of ancient tattooing is typically very elusive. Finding preserved skin at all, let alone tattooed, is incredibly rare. But now, as revealed by new research published last month in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, just such a thing has been discovered.

Anne Austin, lead researcher and bioarchaeologist, told LiveScience, “It can be rare and difficult to find evidence for tattoos because you need to find preserved and exposed skin …. Since we would never unwrap mummified people, our only chances of finding tattoos are when looters have left skin exposed and it is still present for us to see millennia after a person died.” Even exposed skin can be problematic to identify tattoos on: The mummification process tends to discolor the skin, so uncovering tattoos requires special photography.

Austin and her team have analyzed the remains of six tattooed women discovered at Deir el-Medina—a New Kingdom-period (circa 1550–1070 b.c.e.) site located near Luxor, on the west bank of the Nile. It appears that Deir el-Medina likely served as a community town for families whose men worked on the construction of royal tombs. One woman discovered at the site bore over 30 tattoos with various religious motifs on her body, leading researchers to conclude she was some sort of healer or priestess. Further, the researchers combined their analysis of the mummified, tattooed skin remains with various examples of Egyptian “tattooed” figurines.

A common theme among the tattooed women was a connection to the Egyptian god Bes—the protector of women and children, especially during the birth process. Together with this deity, the tattoos depict purification rituals, the eye of Horus and what appears to represent water or a marsh (which could be interpreted as the Nile, a frequently visited location for menstruating or pregnant women). The associated “tattooed” figurines that were discovered at the site also depict lower back and upper thigh tattoos featuring the god Bes.

Researchers do not know conclusively why this female tattoo practice was conducted, but one theory is that it was in connection with the reproduction process, and perhaps the tattoos could have been a kind of amulet of protection either from pain or for a successful birth.

According to Austin, “Tattooing in Deir el-Medina is even more common than people realized.” She is hopeful more evidence of tattooing will be found to better understand if this is a unique phenomenon to this location or, perhaps, a broader tradition in ancient Egypt.

Chronologically, the biblical Exodus out of Egypt took place during this New Kingdom period. It is well known that at this time the Law (Torah) was given to Israel. What is less well known is that several of what now seem like strange, unusual instructions within the Torah are actually an answer to specific and peculiar pagan customs familiar to the Israelites during their stay in Egypt.

Leviticus 19 contains several instructions against such strange (and still debated to this day) customs. Among them is a direct command against tattooing. “Ye shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor imprint any marks upon you: I am the Lord” (verse 28).

Of course, this command against tattooing is not a difficult one to grasp. But it is an interesting one, in light of such archaeological discoveries. Israel had been enslaved in an environment of commonplace tattooing, and as revealed in the context of the new research, it was “even more common than people realized.” As such, this verse constituted God’s warning to the freed Israelites against such a practice.

But the biblical link goes potentially even further. The very following verses discuss women. “Ye shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor imprint any marks upon you: I am the Lord. Profane not thy daughter, to make her a harlot, lest the land fall into harlotry, and the land become full of lewdness” (verses 28-29). Could it be more than coincidence that women and harlotry are mentioned here in the same breath as tattooing, and new evidence from Egypt points to a distinct tattooing practice among women?

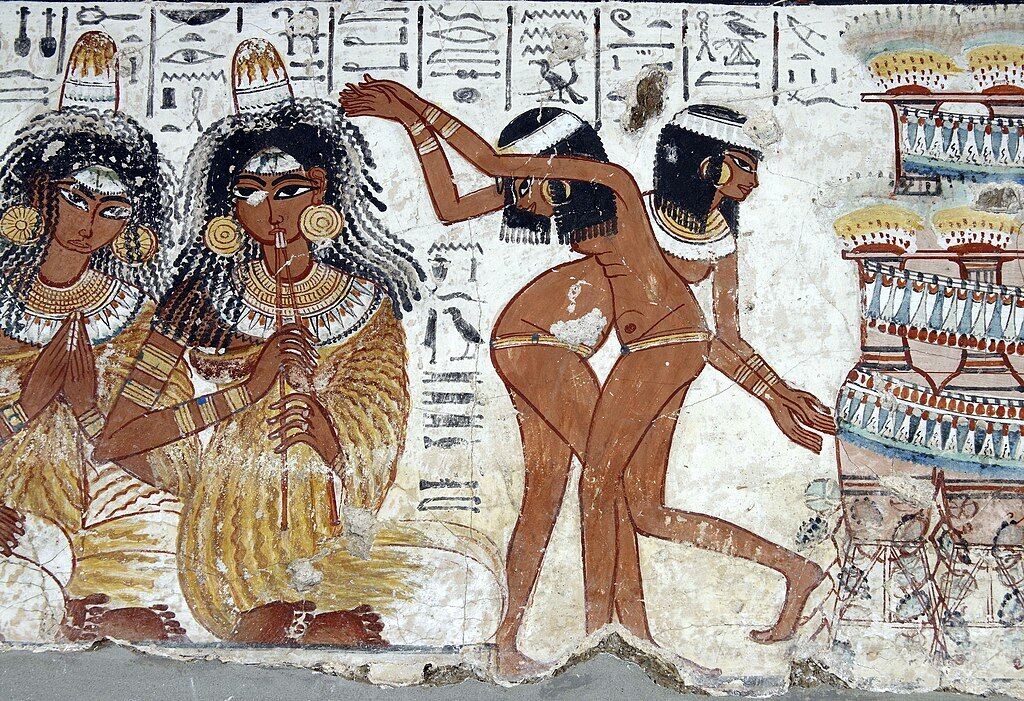

Indeed, the god Bes was a “protector in childbirth.” But he was also a symbol of music, dance and sexual pleasure. As such, New Kingdom-period evidence has also been found of this particularly “well-endowed” god tattooed on the thighs of dancing girls depicted in artwork. (See Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt by Carolyn Graves-Brown for more information—particularly the chapter “Tattoos, Sex and Dancing Girls.”)

Again, is it just coincidence that tattooing is mentioned in the same biblical context as protecting one’s daughters from harlotry? (Also, is it coincidence that to this day the same practice—on the same part of the body—continues as a fad of “erotic appeal” primarily among young women? This style, after all, is certainly not a common practice among men.)

Considering this new analysis of remains from Deir el-Medina, it makes sense that this “common” practice of tattooing in Egypt—and particularly among women, no less—would be something God chose to emphasize for the Israelites to avoid.