Defending Eilat Mazar—and the Biblical Record

In answering scholars who criticize Eilat Mazar’s discoveries of King David’s palace in 2005 and Nehemiah’s wall in 2007, Hershel Shanks recently wrote in Biblical Archaeological Review, “No one would question her professional competence as an archaeologist. Her chief sin, however, is that she is interested in what archaeology can tell us about the Bible” (emphasis mine throughout).

Nothing lures scholarly criticism and hostility out of the woodwork quite like scientific conclusions that actually confirm the biblical record. This is why Mazar’s work is controversial. But as Shanks notes in his column, it’s not like Mazar is the only archaeologist to uncover remains from the ancient kingdom of Israel. Kathleen Kenyon’s excavation on the eastern slope of the City of David during the 1960s, for example, “enabled Nehemiah’s wall to be identified,” she wrote in 1967 (Jerusalem: Excavating 3,000 Years of History). Kenyon excavated in the same general area that Mazar is now digging.

For 10 years, beginning in 1968, Mazar’s grandfather, Benjamin Mazar, excavated 8 acres between the City of David and the southern wall of the Temple Mount. Besides numerous fascinating discoveries from the Ottoman, Byzantine and Roman periods, Mazar also uncovered remains from the royal quarter of David’s dynasty, built during the reign of the kings of Judah.

Digging in this same area during the mid-1980s under the guidance of her grandfather, Eilat Mazar uncovered a large stone gateway complex, 13.7 by 16.5 meters (45 by 54 feet), constructed sometime before the Babylonians sacked Jerusalem in the sixth century b.c.e. Attached to the gate was a short section of the city wall of Jerusalem, built by Solomon. Announcing the news at a press conference in 1986, Mazar said the gateway complex was probably one of 12 gates mentioned in the biblical record. The Associated Press quoted Benjamin Mazar, who attended the briefing with his granddaughter: “Now we have more or less the feeling that this is really a gate of Jerusalem from the period of the kings of Judah” (April 21, 1986).

In 1993, seven years after the Mazars discovered the Solomonic gate, a team digging in northern Israel found a large stone tablet, dated to the ninth century b.c.e., bearing these carved inscriptions: “House of David” and “King of Israel.” It was a stunning discovery—scientific proof that David not only existed, but his kingly reign began a royal dynasty. Two years after that incredible find, U.S. News featured an article on “God’s City”: “The triangular 12-acre city David built lay some 350 feet to the south of the walled Jerusalem of today, on and beyond the eastern ridge called the Ophel. Archaeologists, who have uncovered 21 strata there ranging from the fourth millennium b.c. to the a.d. 15th century, estimate that the Davidic city’s population never exceeded 4,000—largely members of the court. Until recently, the biblical references to David and the city’s structures were not corroborated archaeologically” (Dec. 18, 1995). In the last 15 years, though, archaeological finds mentioned in scriptures have been popping up all over the place.

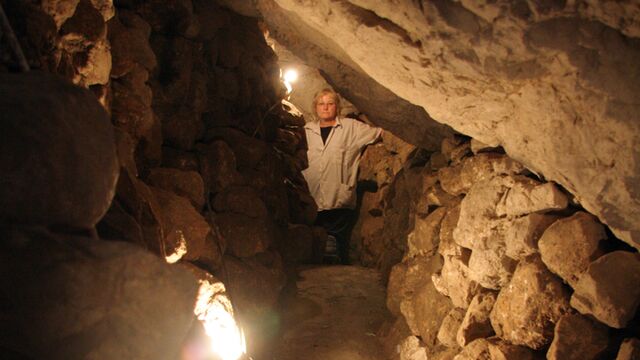

The same year U.S. News printed “God’s City,” construction began on a new visitors’ center in the City of David. Not long after breaking ground, workers were startled to find a wealth of archaeological remains buried deep beneath the surface. Construction work immediately gave way to a massive archaeological excavation. Ronny Reich and Eli Shukron later unearthed remains of a massive fortressed compound built around the City of David’s principle water supply—the Gihon Spring. They also confirmed that the vast underground water system (not counting the tunnel Hezekiah built) pre-dated the Davidic period. 2 Samuel 5:8 says King David’s forces conquered the Jebusite fortress by sneaking into the city through a water tunnel.

In 1997, not long after Reich and Shukron began their work at the Gihon Spring, a biblical verse, also in 2 Samuel 5, caught the attention of Eilat Mazar. Once David conquered the Jebusite city, he took up residence in the stronghold—or the Jebusite fortress at the north end of the city. According to 2 Samuel 5:9, David then began to build up the area around Millo and inward. The New International Version says David “built up the area around it, from the supporting terraces inward.” So David set out to enlarge the city limits—first concentrating on a royal palace. The Bible says King David’s palace was partially built by workers sent to him by the Phoenician king of Tyre as a gesture of friendship (verse 11). “And David waxed greater and greater; for the Lord, the God of hosts, was with him” (verse 10).

Near the end of David’s palace construction, the Philistines attacked. And since the new palace may not have been reinforced strongly enough to withstand the Philistine assault, verse 17 says David went down to the citadel to barricade himself within the city walls until the conflict ended. This, Eilat Mazar theorized more than 10 years ago, indicates that David’s new palace stood on higher ground than the Jebusite fortress. She published her theory in Biblical Archaeology Review in January 1997. Under the title, “Excavate King David’s Palace,” on a two-page spread picturing an artist’s rendering of the ancient City of David, Mazar drew an arrow pointing at the north end of the city, underneath the caption “it’s there.” She wrote,

“Careful examination of the biblical text combined with sometimes unnoticed results of modern archaeological excavations in Jerusalem enable us, I believe, to locate the site of King David’s palace. Even more exciting, it is in an area that is now available for excavation. If some regard as too speculative the hypothesis I shall put forth in this article, my reply is simply this: Let us put it to the test in the way archaeologists always try to test their theories—by excavation.”

In the nine-page article, Mazar cited Kathleen Kenyon, Benjamin Mazar, Yigal Shiloh and several other scholars—oh, and also the Bible. Maybe that “chief sin” is one reason why Mazar found it difficult to obtain the financial support needed to test her theory. Or maybe it was because so many archaeologists had already excavated around that location. Whatever the reason, it took eight years for Mazar to receive the funding needed to excavate.

Within months of beginning her dig in 2005, Mazar’s team uncovered what she later called a Large Stone Structure—a wall running east-west that she believed to be the northern facade of David’s palace. Only 10 percent of the structure was exposed during the first phase of digging. But it was enough to reveal that this was not a common house, but rather a “fantastic house.” Her most significant discovery was in identifying the relationship between the Large Stone Structure and the Stepped Stone Structure on the city’s northeastern slope. “It can already be said with some certainty,” she wrote in her first phase report, “that the two are part of a single, enormous building complex. The Stepped Stone Structure, so it appears, was built as a gigantic, well-devised supportive structure that allowed for the erecting of a great podium on which the Large Stone Structure, which is identified with King David’s palace, would be built.”

The first phase also turned up the Jehucal bulla, which we have written about before. Jehucal was a royal officer who worked in the administration of King Zedekiah, Judah’s last king before going into Babylonian captivity during the sixth century b.c.e. Jehucal is referred to twice in the book of Jeremiah (37:3; 38:1).

During the second phase of her excavation (winter of 2006-07), Mazar uncovered a massive wall on the eastern side of the royal complex, measuring 5 meters thick. Mazar has also located the seam between this eastern wall of the palace and the Stepped Stone Structure.

During the third phase, while excavating under a tower on the Stepped Stone Structure, Mazar discovered large quantities of pottery and other artifacts which dated the tower’s construction several hundred years earlier than previously thought. It was actually built during the Persian Empire’s heyday, which is precisely when the Bible says Nehemiah rebuilt the wall around Jerusalem.

Not long after Mazar announced that she had located a section from Nehemiah’s wall, she found a black stone seal, bearing the Hebrew inscription “Shlomit,” which some scholars believe might have belonged to Shelomith, the daughter of Zerubbabel, referred to in 1 Chronicles 3:19.

This week, Dr. Mazar told me that the third phase of her dig is nearly complete. She said they continue to “uncover and discover wonderful things.” She is anxious to begin the office phase of the excavation, when she can begin the tedious work of processing her findings.

Meanwhile, a short distance from Mazar’s dig, near the Western Wall, other fantastic discoveries are turning up. Just yesterday, the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that archaeologists had uncovered a “rich layer of finds from the latter part of the First Temple period.” According to its website, “This is actually the first time in the history of the archaeological research of Jerusalem that building remains from the First Temple period were exposed so close to the Temple Mount—on the eastern slopes of the Upper City. The walls of the buildings are preserved to a height of more than 2 meters.” Other findings, the report noted, include a stone seal with an inscribed Hebrew name and numerous figurines—all “characteristic of the Kingdom of Judah in the latter part of the First Temple period.”

And yet, even as these now-frequent discoveries are being made, all confirming the biblical record, there has been a corresponding rise in the level of hostility from scholars who reject the conclusions made from these findings—not because they question the credentials of the archaeologists, but because they reject the word of God.

Dr. Mazar’s “chief sin,” as Shanks points out in his recent column, “is making a reasonable judgment about archaeological evidence as it relates to the Bible. In some scholarly circles,” he wrote, “this is considered ‘unscholarly.’ If the judgment she made related to something other than the Bible, no one would give it a second thought. Only a finding related to the Bible brings such obloquy down on the head of a leading archaeologist.”

A few years ago, Dr. Mazar criticized the modern scholarly approach to archaeology—that of discounting the biblical record as false unless it can be proven true. In fact, it’s worse.

Even when proven true, many scholars still reject it.