Childbirth: Evolution, the Bible and Archaeology

According to the theory of evolution, man has had a few million years to sort himself out in terms of bodily functions, organs and apparatuses in his divergence from the monkey realm. Hence why we are such efficient, well-developed and equipped beings. But for the Bible-believer, these are signs of God’s perfect creation. It is true that we run like well-oiled machines; except for one notable, most natural, exception.

Childbirth.

The beauty of human reproduction, pregnancy and bringing a new life into the world is often termed as a “miracle”—and that it is. But childbirth is also a risky, painful and even deadly matter, as Colin Barras wrote in a bbc article “The Real Reasons Why Childbirth Is So Painful and Dangerous.” He wrote:

The World Health Organization estimates that about 830 women die every day because of complications during pregnancy and childbirth—and that statistic is actually a 44 percent reduction on the 1990 level.

“The figures are just horrifying,” says Jonathan Wells, who studies childhood nutrition at University College London in the UK. “It’s extremely rare for mammalian mothers to pay such a high price for offspring production.” … Even among women who do not lose their lives during childbirth, some studies say the process leads to life-changing but non-lethal injuries in as many as 40 percent of cases. The price women pay for childbirth seems extraordinarily high.

That’s not to mention the untold numbers of children lost during pregnancy and childbirth. From an evolutionary perspective, those numbers are just not “normal.” Why, for humans, is pregnancy and childbirth so difficult? In this article, we’ll pit evolution’s explanations against the biblical account, and also look into some remarkable archaeological discoveries that fill in our history of this fascinating part of human life.

According to Evolution

Human babies are unique—that’s an understatement. Compared to primate offspring, babies have very large heads containing very large brains. And relatively speaking, they are also carried in the womb for significantly longer—37 days longer, to be precise, than would be the case for an ape of equivalent body mass.

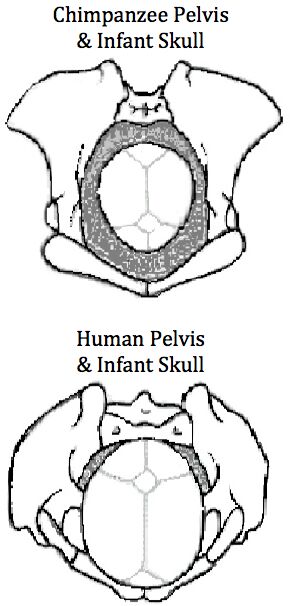

The reason all of this becomes problematic is when considering unique female human anatomy. The human birthing canal within the pelvis isn’t straight, as it is with the majority of primates. This requires a newborn to twist and turn. And—from an evolutionary perspective—womens’ hips are too disadvantageously narrow. The birth canal is far more restrictive than for primates, as is illustrated on the right (the chimpanzee is considered to be our closest “cousin”). In fact, the average human infant’s skull is 102 percent the size of the mother’s pelvic cavity (at the end of pregnancy, a hormone weakens cartilage in the pelvic joints, allowing them to expand).

This all comes together into what is known as the obstetrical dilemma, the standard evolutionary explanation for the difficulty of childbirth—centered on our unique human trait of walking upright. The obstetrical dilemma theory states that because we walk upright, the hips necessarily became narrower for more efficient locomotion, and the pelvis and birthing canal became distorted. The trade-off for this “improved” locomotion is that childbirth became more difficult. This concept has also been used to explain differences between male and female gait and power output. Put simply, it dictates that females’ wider pelvises decrease the effectiveness of certain muscles used during walking and running, thus requiring those muscles to produce more force to match the equivalent efficiency for the male counterpart. In order to reach maximum efficiency, a woman’s pelvis would have to be as small as possible, yet still be able to birth large-brained children.

But new research conducted by Harvard University has shown the “obstetrical dilemma” to be theoretical junk-science. Experiments were carried out on male and female volunteers walking and running in a lab environment. Data showed that varying hip width has no impact on efficiency or energy output. “From purely energetic considerations, at least, there does not seem to be anything stopping humans evolving wider hips that would make childbirth easier,” Barras wrote (op cit). And so the problem of figuring out why human childbirth is so difficult remains. “[I]f evolution could have ‘solved’ the problem of human childbirth by simply making women’s hips a little wider and the birth canal a little larger, it surely would have done so by now,” he wrote.

As such, we are left with other shotgun-type theories for why childbirth is so dangerous. One is the transition of our ancestors from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a farming, agricultural lifestyle. A carbohydrate-rich diet can bulk up a developing baby. (However, evidence now shows that our image of mammoth-hunting early man is wrong. Instead, our early ancestors subsisted on a significantly vegetarian diet.) Another theory is that the baby’s brain uniquely requires a huge amount of energy to grow. This is incredibly taxing on the mother, and the large size of the head compounds the problem. But this causes us to question why humans have such a comparatively large brain—when, as a newborn, they are much more helpless than their primate “cousins.” Another theory is that the length of the pregnancy is governed by the amount of effort it takes to develop a baby, rather than the size of the birth canal—that after 40 weeks, the mother is maxed out.

As with most things, the evolutionary perspective is we just don’t know.

According to the Bible

The biblical explanation of origins, found in the book of Genesis, is quite clear and unequivocal. The story of Adam and Eve is well known. (What is not so well known, however, is the sheer amount of genetic, archaeological, and morphological evidence pointing to the biblical account of Adam and Eve. You can read about that in detail here.) Genesis 3 describes Adam and Eve’s decision to eat from the forbidden tree, and thus chart their own course in life, cut off from God (verses 22-24). Mankind since has, in our own way, made the same choice. Hence, the human condition to this day is fraught with war, death, destruction and unhappiness.

After Adam and Eve’s sin, both man and woman incurred a number of specific curses. To the woman God said, “I will greatly multiply your sorrow and your conception; in pain you shall bring forth children; your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you” (verse 16, King James Version).

Here is a very clear statement—certainly not like typical scholarship’s possibly, maybe, could be, seems to be. We have a straightforward question: Why is it that humans, as a species, so uniquely struggle with painful childbirth? And a clear, straightforward answer: Unlike the animals, we were cursed, because of sin, from the beginning.

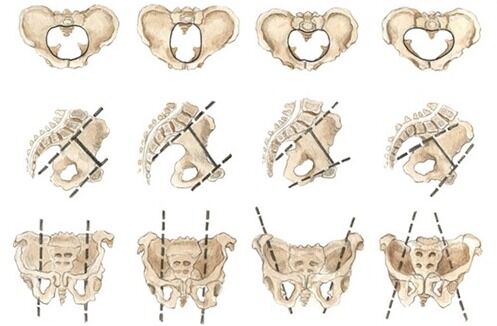

The Bible makes it plain that Eve wasn’t originally created in this manner. Evidently, something changed in order to make childbirth much more difficult. Perhaps the birth canal became smaller or more irregular. The birth canal is known to be exceptionally high in irregularity among women—more skeletal variance exists in the birth canal than the arm bone, which is well-known as a highly variant structure. (Science is at a loss to explain why this is the case.)

It is also interesting, as mentioned above, that scientists are now speculating on whether farming practices contribute to difficulty in childbirth. After all, when God cursed Eve, He also cursed Adam and the ground (Genesis 3:17-19).

So that is where the pure physiology sits. The modern evolutionist is left scratching his head, while the believer’s views have not changed since Genesis was “penned” 3,500 years ago.

What about the archaeological record? What does this field of science reveal about mankind’s history of childbirth?

According to Archaeology

Childbirth, of course, is well documented in the historical record. Ancient artifacts related to the subject include inscriptions, wall art, figurines and more. And of course, just as it is today, childbirth was a risky process. Infant mortality rates were much higher, too, due to lack of sanitation and the spread of disease.

Childbirth for the ancients became an extremely pagan ritual, featuring various talismans and incantations. An example of this is Bes, one of the chief Egyptian gods of childbirth, a grotesque man-lion figure with enlarged genitalia. This god was widely worshiped during the New Kingdom period (16th–11th centuries b.c.e.). One of our students discovered a Bes figurine, in the form of a neck-worn pendant, during our participation in Dr. Eilat Mazar’s Ophel excavations in Jerusalem. This idol dated circa 1100 b.c.e.

Through archaeology, we find some interesting corroboration for the biblical accounts of childbirth.

Exodus 1 describes the pharaoh’s command to the Hebrew midwives to kill all newborn males. Some interesting terminology is used. “When ye do the office of a midwife to the Hebrew women, ye shall look upon the birthstool: if it be a son, then ye shall kill him; but if it be a daughter, then she shall live” (verse 16). The general consensus is that “birthstool” here means, literally, two stones. Essentially, this was an early form of birthing chair. The mother kneeled, sat, or squatted on the stones/bricks, assisted by gravity in birthing the child. A bowl of boiled water, sometimes with herbs, could be placed between the bricks, the steam designed to ease the delivery. The midwife delivered the child between the stones, and in the case of the Israelites, if it were revealed to be a boy, it was to be immediately killed.

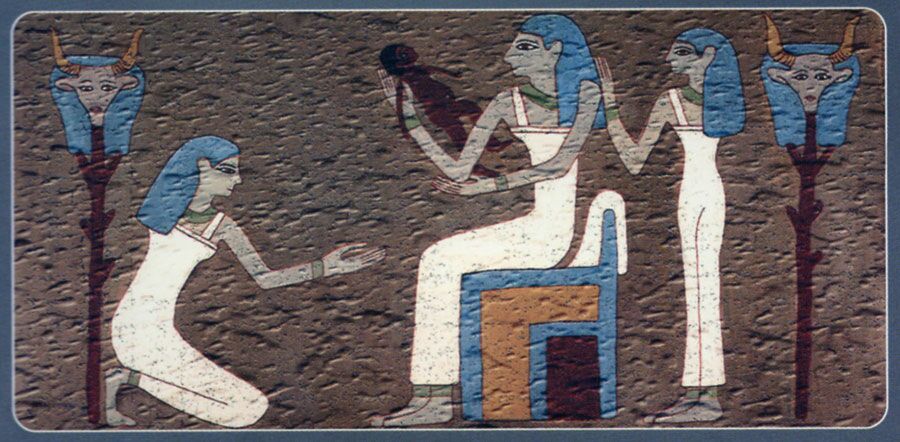

Archaeology has revealed much about this Egyptian method of giving birth, and even the biblical phraseology is paralleled by the ancient Egyptian phrase “He left me like a woman on the bricks” (or again, “upon the stools”). These bricks were typically highly decorated with magical scenes in order to incur blessings from the gods. An Egyptian hieroglyph for childbirth even depicts the scene of giving birth “on the stools” (see right). These birthing bricks were well known from papyrus texts, but it was not until 2001 that the first one was discovered, dating to circa 1700 b.c.e. (see the image below).

As an aside: Shiphrah is one of the midwives mentioned in Exodus 1. This name has been found documented on an early Egyptian papyrus slave list, dating to the early part of the Egyptian captivity—circa 1700 b.c.e. It is impossible to say whether this woman is the same one mentioned in the Bible, but it certainly proves the authenticity of such a name being used among the slave classes during the period of Egyptian captivity. Further, the northern delta city of Avaris (located in the territory of Goshen) seems to have a strong connection to the Israelites and may have been their “capital” while in Egypt. It was known as a chief city of foreigners, and the name has a link to the Hebrew pronunciation of “Hebrews”: Ivrim. Avaris was occupied by “foreigners” during the time frame of the biblical sojourn in Egypt—foreigners who were “expelled.” An exceptionally high child mortality rate was discovered from analyzing skeletons found at the site—even compared to the already high child mortality rate of the ancient world. Out of 257 skeletons analyzed, 82 belonged to children aged 0-6 years old. That’s 1 in 3 not making it past early childhood—again, possibly attesting to the “cleansing” of the Hebrew males. (The researchers were not able to determine the gender of the skeletons.)

Continuing with birthing customs: In ancient history, childbirth was generally a women-only event. The practice of having men in the room for the labor is a relatively recent phenomenon, only having become a common practice over the last half-century. (A 15th-century German physician was actually sentenced to death after dressing as a woman in order to be present in the birthing room.) Fathers would typically wait in a separate area. This was certainly the case in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. Jeremiah 20:15 is an example of a messenger informing Jeremiah’s father of his birth and gender. Ancient art depicting childbirth virtually exclusively shows a women-only scene.

Further, the biblical description of what is done with the newborn after birth is shown to be accurate: Evidence of “swaddling” the baby has been dated back as far as circa 4000 b.c.e. (e.g., Ezekiel 16:4). Ancient figurines depict swaddled children. Further, “salting” a baby’s body after birth is an age-old practice. It is mentioned in Ezekiel 16:4, written during the sixth century b.c.e.—there is no real dispute about this dating of Ezekiel. Extra-biblical references to this practice cover at least the past 2,000 years, and it has generally been seen as a practice from “time immemorial,” originating somewhere in the ancient Middle East. The reason for it seems to be to make the skin firm and to purify the infant. (As a warning: The improper application of this tradition can lead to serious complications for the child.)

Leviticus 12 describes periods of quarantine/purification following the birth of a child. The Egyptian Westcar Papyrus (roughly circa 1700 b.c.e.) references a similar practice: a mother of triplets spending 14 days in purification after the birth.

Surrogacy

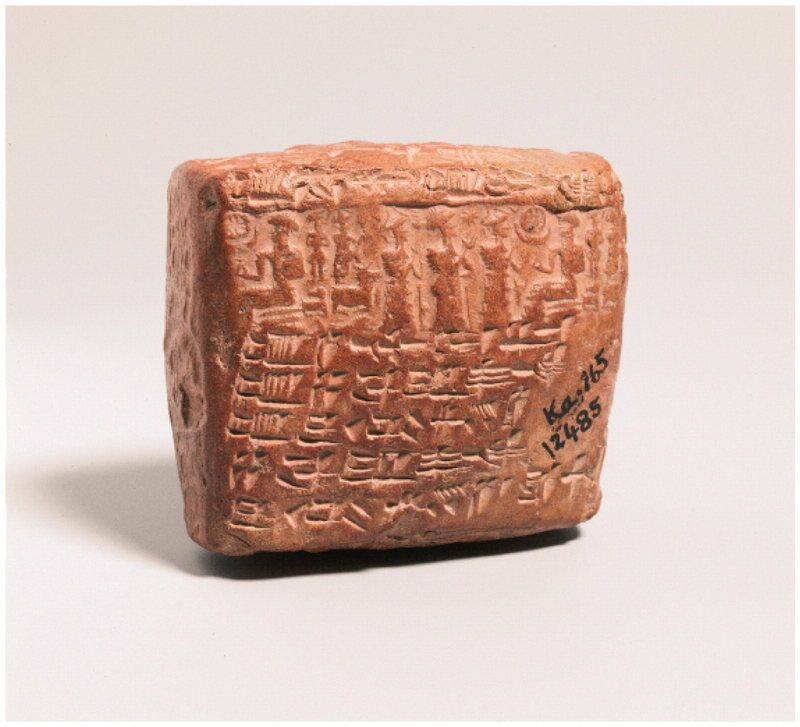

An interesting tablet from Kültepe-Kanesh, Turkey, was discovered two years ago, dating to circa 2000 b.c.e. The tablet is a marriage contract, stating that if the couple cannot produce a child after two years, then a slave will be brought in as a surrogate mother to produce a male descendant for the husband and wife. The slave-mother was then to be set free after giving birth to a male. The tablet’s parallels to the story of Hagar, which takes place in roughly the same period, are unmistakable. “And Sarai said unto Abram, Behold now, the Lord hath restrained me from bearing: I pray thee, go in unto my maid; it may be that I may obtain children by her. And Abram hearkened to the voice of Sarai” (Genesis 16:2; kjv).

In several cases, time limits were given for bearing children before marriage to a second wife was acceptable. Texts from Alalakh give the wife a period of seven years to bear children before the husband was allowed to take a second wife. This was likely the same concept taken up by the Prophet Samuel’s father, Elkanah. His favorite wife, Hannah, was childless, while his other wife, Peninnah, had many children. It is likely that he married Peninnah after it was realized that Hannah could not bear children (1 Samuel 1—hence the family strife).

Biblical levirate marriage involves a childless widow marrying the brother of her dead husband in order to raise up children to the dead husband’s name and to keep property within the family (Deuteronomy 25:5-10). Parallels of this ancient practice have been found during the same period (1500 to 1000 b.c.e.) among the Assyrians, Hittites and Hurrians.

Proof Against the Biblical Account?

There are two biblical passages, both dealing with a similar subject, that receive some ridicule from the critics. They are the accounts of both Rebekah’s and Tamar’s labor (Genesis 25 and 38, respectively). Both women were pregnant with twins, and both accounts describe a hand emerging first. Critics assume that since the men of antiquity were generally not present for the birth, in their ignorance they would have assumed human birth to be the same as the delivery of livestock. Frankly, this sets a pretty low bar of intelligence for the biblical author! Rather than being a piece of fiction written by dolts, the Bible—including this book of Genesis—contains advanced medical and scientific knowledge that has only just been rediscovered in modern times. But of course, the critic’s attempt to dismiss the Bible by any means necessary has led to some laughable theories.

Actually, both accounts describe only one hand emerging first—not an “animal”-style two-hand birth. And, while relatively rare, this is a recognized birth position—called the nuchal hand. In this position, the baby’s hand is extended around the neck or even beyond the forehead, in a “superman”-type position. Obviously, birthing a baby in this position is far more painful, with a much higher potential for tearing. Still, it is not unusual to hear of this type of birth. Further, only one of the babies—Jacob—is described as being fully born in this manner. Tamar’s baby, Pharez, merely pokes his arm through the birth canal and then withdraws it. This can’t be branded as impossible, if the baby is in precisely the right position (and taking into account a newborn’s arm length, length of the birth canal, and degree of dilation). This article, while not describing the same degree of arm extension as for Pharez, does illustrate a case of a midwife having to push a newborn’s hand back into the womb so that the head could be properly applied to the cervix. Again, neither of these biblical examples are beyond the realm of possibility. And for the Bible-believer, both appear to have happened as a result of divine intervention and each case intended to illustrate a key point.

In Summary

In her article “Pervasive Practices and Divergent Cultural Traditions Surrounding Childbirth in Ancient Egypt and Ancient Mesopotamia,” Prof. Christine Johnston makes a short, but fundamental, statement: “One of the best sources documenting attitudes and spirituality associated with childbirth is the Hebrew Bible itself” (emphasis added). There is no record like the Bible, as a complete, historical document. And not only have numerous discoveries attested to the authenticity of the biblical account, so too has Bible aided in understanding parallel secular accounts, and how ancient Middle Eastern communities interacted and handled childbirth and child rearing in different manners.

And if the Hebrew Bible is “one of the best sources” for understanding ancient childbirth, could it not also be “one of the best sources” for explaining the origin of childbirth, and how it came to be—uniquely for humans—such a difficult and risky process?