Let the Stones—and the Science—Speak

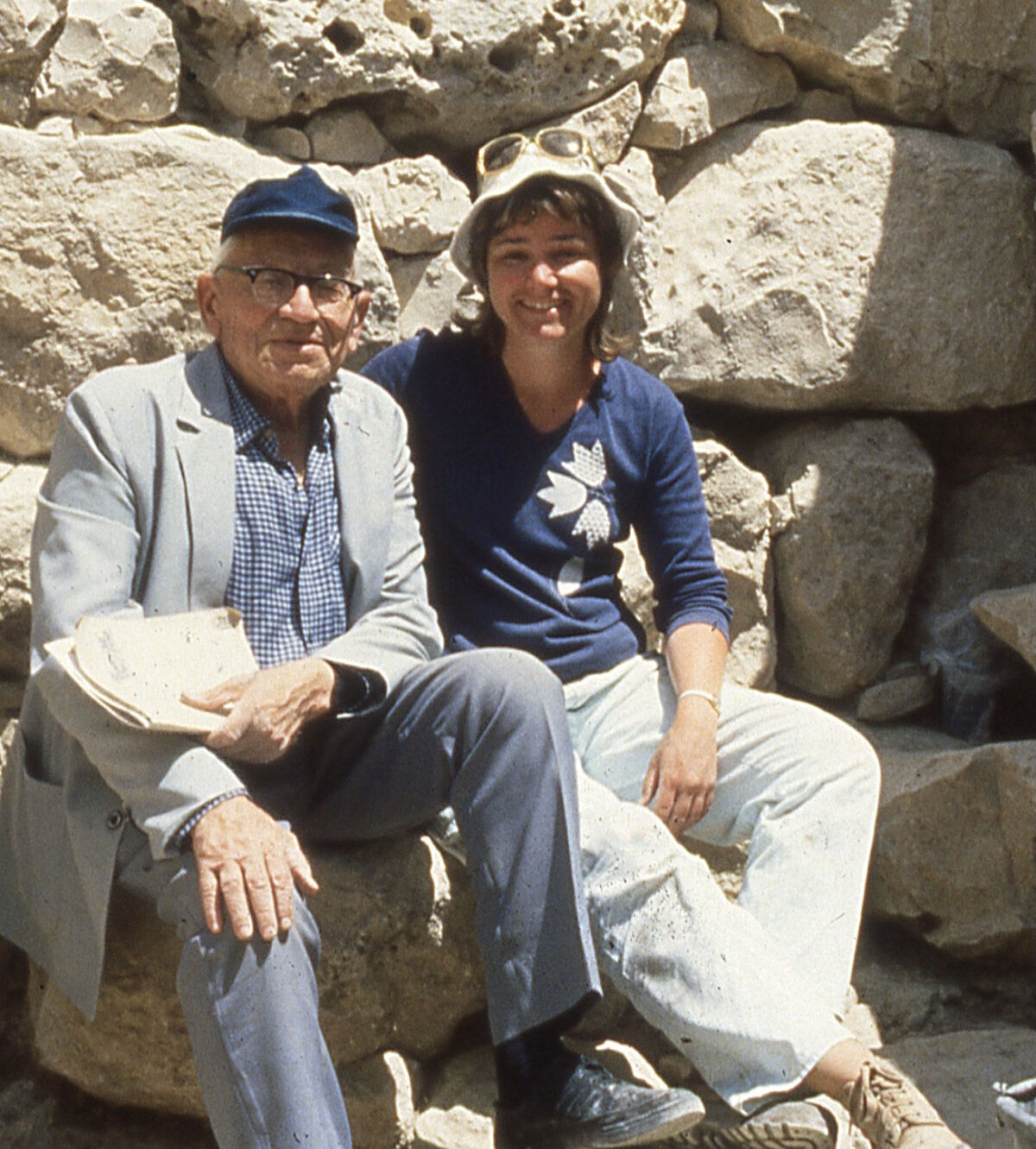

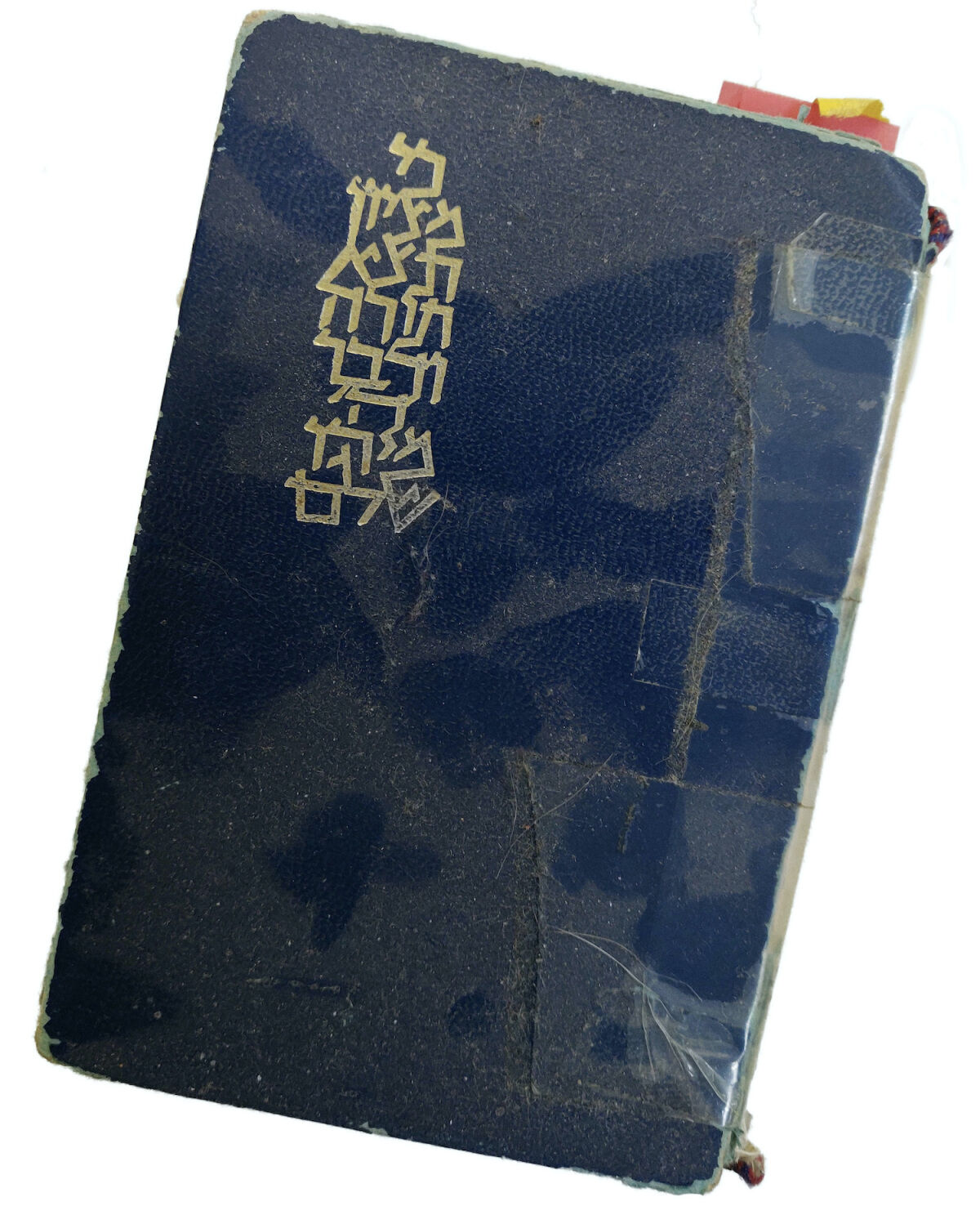

A few weeks ago, I found a little blue book. I was moving boxes inside the cluttered office of the late Dr. Eilat Mazar, which, aside from a couple of laptop computers, probably looked exactly like it did when it was occupied by Eilat’s grandfather Prof. Benjamin Mazar, eminent archaeologist and former president of Hebrew University.

Desks, shelves, drawers and metal closets were covered and filled with books, final excavation reports, binders, field notes, photographs, excavation maps and even boxes of unpublished artifacts, all representing two lifetimes of scientific work. But this tiny blue book caught my eye.

The pages were dog-eared, wrinkled and discolored after decades of dusty fingers passing through them again and again, making so many highlights, underlines and handwritten notes in pencil and in blue and black ink that much of the print was hard to read.

It was a copy of the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible. Inside the cover, it bore two names—Benjamin Mazar and Eilat Mazar.

I worked with Dr. Mazar for more than 15 years. She had told me enough stories about her grandfather for me to know that she inherited this trait of highlighting and marking from him, just as she inherited this book: Even though neither she nor he was religious, the reason they left behind such a heavily marked Hebrew Bible is that they both used it—heavily—as part of their archaeological work. Even still, I was moved by their obvious affection for the Bible.

I thought about the advice Professor Mazar had given Dr. Mazar, and that she had given me: “Pore over it [the Bible] again and again,” he said, “for it contains within it descriptions of genuine historical reality.”

These two scientists practiced what they preached for almost a century. Then I thought, Who is going to keep this work alive?

Professor Mazar’s use of the Bible was natural for him: He was known for carrying it everywhere he went. Dr. Mazar’s use of the Bible was natural for her. But using the biblical record is unnatural for most modern archaeologists. Journalist Andrew Lawler recently wrote, “[U]p until the end of her life, she remained one of the last university scientists digging with a spade in one hand and a Bible in the other, eager to uncover clues to the people and places described in Scripture” (Aeon, Dec. 10, 2021).

With Dr. Mazar gone, what will be the future of biblical archaeology?

‘Let the Stones Speak’

One of Dr. Mazar’s most famous phrases was, “Let the stones speak.” She used it in almost every interview, and I probably heard her say it dozens of times. In a way, it perfectly embodies her archaeological approach.

What did she mean by this? Some of her peers argued that what the stones and artifacts reveal requires interpretation, and obviously it does. So why did Dr. Mazar keep saying, “Let the stones speak”?

Discoveries made in excavation rarely interpret themselves. Usually, material uncovered in excavation provides only a narrow understanding. The best that science can do of itself is inform us about the material culture of the people: the types of vessels they used, the weapons they fought with, the tools they employed for industry. Through careful excavation, archaeologists are then able to determine when the items were used. If they can know this, then they can date the structure in which they were found. All of this is important archaeological information. But absent historical records and accounts, they tell us little about the broader nature—the culture, history and behavior—of the actual people who used them.

For example, ancient pagan idols have been uncovered across Israel, though they have been present in certain time periods but missing in others. Why is this? Did the idolaters suddenly become atheists? If we only considered the idols, it’s impossible to understand the full picture. But when you consult the ancient text, you find specific records that one Jewish king led one generation of Jews in idolatry, and the next not only discontinued their use but eradicated them from the territory almost completely.

Without a historical text, our understanding is incomplete and largely conjecture. With a historical text, our understanding becomes fuller, richer and more accurate.

Dr. Mazar excelled at explaining relationships of artifacts, buildings and stones to human history. Why? Because the ancient text Eilat relied on so heavily was the best, most scientifically and historically accurate source available for the land of Israel.

“Archaeology cannot stand by itself as a very technical method,” Eilat once told me. “It is actually quite primitive without the support of written documents. Excavating the ancient land of Israel and not reading and getting to know the biblical source is stupidity. I don’t see how it can work. It’s like excavating a classical site and ignoring Greek and Latin sources. It is impossible.”

Dr. Mazar did not consider the Bible divine; she actually thought that some of its records could have been subject to exaggeration or error (like Greek, Latin and all other historical sources). Yet for her and her grandfather, “there was no question about the Bible reflecting history, [and] there was no real reason to assume, ever, that what the Bible tells us is not a historical source.”

Dr. Mazar, no more devout than the next archaeologist, could not practice science in good faith without using Bible history. It was impossible for her to uncover ruins and artifacts that obviously matched biblical records and to pretend that they did not. She strove to approach her study with humility, to put aside personal bias, to ignore peer pressure, and to give voice to the truest account for what had been uncovered. She let the historical text and the discovery itself do the talking. She let the stones speak.

She was, in a word, intellectually honest. And remarkably, that made her controversial.

Using and Misusing the Historic Text

How did we arrive at the point where many archaeologists consider using Bible history to be a relic of a past era of archaeological research?

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, when the field of archaeological exploration across the Middle East began, most of the scientists were firm Bible believers. Archaeologist G. Ernest Wright wrote in Biblical Archaeology (1957), “The Bible, unlike the other religious literature of the world, is not centered in a series of moral, spiritual and liturgical teachings, but in the story of a people who lived at a certain time and place” (emphasis added).

However, many early archaeologists were too hasty to connect their discoveries to the Bible. Mistakes were made. One archaeologist placed biblical Sodom and Gomorrah south of the Dead Sea in locations that dated to the wrong period; another found evidence of an ancient local flood in Mesopotamia and claimed he’d found proof of the biblical flood. While 19th-century explorers such as Edward Robinson were surprisingly accurate in locating biblical places, they were extremely limited in their ability to date their finds.

Not until the 1930s did archaeologists improve dating accuracy, particularly through excavations by William Foxwell Albright at Tel Bet Mirsim, as well as the work of Wright. They were able to map changes in pottery styles to the passing of time. By the 1950s, archaeologists were armed with improved scientific methods and capable of testing the interpretations and conclusions of the early fundamentalists, some of which were shown to have been flawed.

The new archaeologists, many of whom were Bible skeptics, claimed that the early archaeologists were wrong because they relied on the Bible. They identified the Bible as the chief reason for the mistakes in interpretation. Their reasoning went something like this: Early archaeologists used the Bible and it caused them to make some terrible mistakes. Therefore, we must not use the Bible in our practice of archaeology.

But this reasoning isn’t logical. The Bible wasn’t responsible for those mistakes in misdating and misnaming. The problem was with those interpreting the archaeology and the Bible history.

Yet today this anti-Bible bias is firmly entrenched. One commentary on the biblical world published last year highlighted this change, asserting that the biblical books relating to the kings of Judah and Israel should not be considered a primary historical source. “In 1982, it was still possible to write in relation to Iron iiv, that the ‘primary sources of knowledge for the period of the divided monarchy in Judah and Israel … are the books of the Bible, complemented by contemporary inscriptions and by the results of excavations.’ This claim,” wrote James E. Harding, “now appears naive” (The Biblical World, Second Edition).

Is the anti-Bible view that now dominates this field the result of scientific fact? Or is it a function of the same anti-Bible bias that now courses through education, politics and other fields of science, from microbiology to astronomy?

“Today, it is very common to throw the baby out with the bathwater,” writes Hebrew University Prof. Yosef Garfinkel in Debating Khirbet Qeiyafa. “This is part of the much wider realm of intellectual developments formulated in the West during the last decades of the 20th century. Today, we are in a postmodern and deconstructive era. Everything is relative, there is no right or wrong, and contradictory approaches are all legitimate.”

Professor Garfinkel has seen firsthand how this post-truth view is infecting biblical archaeology. Garfinkel excavated at Khirbet Qeiyafa, a Davidic-era site between Jerusalem and Gaza. His motivation for digging Khirbet Qeiyafa had nothing to do with the Bible or seeking to prove the biblical account of King David. In fact, David wasn’t even on his mind.

However, as excavations progressed and 3,000-year-old remains were uncovered, all the ethnic and political markers pointed to the fact that Judah controlled this site.

Professor Garfinkel faced a choice. While he hadn’t set out to “prove the Bible,” the archaeology at Khirbet Qeiyafa correlated well with its record of David’s kingdom. Garfinkel could have remained silent, but he did what any honest archaeologist would do: He linked his discoveries with a contemporary historical source that describes the time and place in question.

He let the stones speak. And they said the same thing as the contemporary historical source: the Bible.

Unfortunately, Garfinkel’s colleagues have engaged in an impassioned and unscientific attack on his identification of the site as being controlled by Judah. While their arguments do not present a more probable scientific identification, they have muddied the waters and created enough confusion to leave many onlookers uncertain of what to believe.

Quality Archaeology

A contemporary eyewitness is generally the most reliable source for describing an event. Generally, the more time that elapses, the more opportunities arise for error. This is why some scholars routinely assert that the authors of the Bible wrote their books as long after the events as possible. This makes it easier to question or dismiss Bible records. But are these scholars following the science, or are they exhibiting their overall anti-Bible bias?

“Arguably, the most problematic sources are the books of the Hebrew Bible,” Harding writes, “not because of their inherent biases and prejudices … but because they are composed of a complex variety of highly redacted sources, which were for the most part compiled, edited and collated long after the events to which they purport to refer, … What primary sources do still exist within the Hebrew Bible are now found in secondary, or even tertiary, contexts. [T]he biblical sources must thus be read with a critical eye on their ideological biases and complex literary growth, but they should not be sidelined entirely” (op cit).

The cost of marginalizing the ancient text is not insignificant, and scholars who take this highly skeptical view of Bible history are often more limited in their archaeology. An archaeologist with this view could never have done what Dr. Mazar did to uncover the palace of David. He would never study 2 Samuel 5:17 and accept its literal interpretation, then use the verse to develop a scientific hypothesis, and then eventually uncover a massive 10th-century b.c.e. structure (see sidebar below).

The scholarly jury is definitely still undecided on when the Bible was first authored. The records of David’s life, they say, could have been written during his lifetime (later 11th century through early 10th b.c.e.) to as late as the fifth century b.c.e. Scholarly consensus for the dating just does not exist.

Even if the records of David’s life were edited one final time hundreds of years after he lived, that would not necessarily invalidate those records.

“[M]inimalist scholars … assume that the time at which a certain biblical tradition was written, edited or received its final shape is also the time that the text describes,” Garfinkel writes. “If a visitor to Paris today sends a letter with a description of Notre-Dame Cathedral, the construction of the cathedral according to minimalist methodology, should be dated to the 21st century c.e. Along the same lines, the play Julius Caesar, written by Shakespeare in the late 16th century proves, according to minimalist theories, that Julius Caesar is a purely mythological figure. …

“As far as the archaeology of the southern Levant in the Iron Age is concerned, one simply cannot ignore the main historical text that has reached us from antiquity” (0p cit).

Honest mistakes and intellectual dishonesty have occurred on both sides of the debate over whether to consult the Bible for Middle East archaeology. But archaeologists still must face a choice. Each must decide for himself whether consulting this ancient record is intellectually honest—and whether they want to use it in their science.

What would be the immediate future of biblical archaeology over the next months and years if we cleared out the blatant bias, applied modern tools, methods and knowledge, and used the Bible for what it is: an ancient source containing a number of historical facts verified by archaeology?

It’s not too hard to speculate. A monumental structure in the City of David, and a well-worn little blue book from a cluttered office at Hebrew University, give us a good idea of what is to come. We just need to follow the example of Dr. Mazar and let the stones speak.

Sidebar: Searching for David’s Palace

An archaeological excavation can be an extremely expensive endeavor, often subject to numerous, time-consuming academic and political hurdles, especially in Jerusalem. The location also determines what, if anything, you will find. This is why archaeologists, when deciding where to dig, consider as many facts as possible.

The ancient structures that archaeologists can learn from the most are typically the city gates, palatial structures and places of worship. During excavations in the City of David in the 1980s, Dr. Eilat Mazar noticed a geographical feature mentioned in the Bible that could help identify the location of David’s palace. To pinpoint the possible location, she did what most scientists would never consider doing: She consulted the Bible.

Critical to her theory was 2 Samuel 5:17. This verse states that when a Philistine force approached Jerusalem, King David “went down to the hold.” If the biblical text was accurate, as Eilat believed, this meant that David’s palace had to be situated adjacent north of Jerusalem.

“[T]here is no reason to doubt the accuracy of the biblical description,” Andrew Lawler quoted Dr. Mazar as saying. “The Bible is quite careful in its use of going up and going down.” Lawler then inserted, “This was just the sort of literal interpretation that many of her colleagues avoided, given that the biblical accounts of this era were written several centuries later by scribes with a political agenda” (Aeon, Dec. 10, 2021).

Many scholars view the Bible as unreliable because it is theological and because some of its records were recorded centuries later. Yet they readily rely on other sources that were written by flawed, biased people centuries after the fact.

One wonders, for example what political gain a Jewish scribe writing hundreds of years later would achieve by making up the fact that David “went down to the hold” rather than writing something else, or writing nothing at all. Fictions or flaws on the part of the scribe would have been subject to fact-checking, since his contemporaries knew the geography of Jerusalem. A rational approach, like Dr. Mazar’s, would conclude that the scribe who wrote that David went down to the hold did so because that is exactly what David did, and it was deemed important to record that fact.

In any case, the best way to test such a hypothesis is to dig. That is exactly what Mazar pushed for, for years. The January-February 1997 Biblical Archaeology Review published “Excavate King David’s Palace!”, by Eilat Mazar, and it included an illustration of ancient Jerusalem, a large arrow, and the words “It’s there.”

“[A] careful examination of the biblical text combined with sometimes unnoticed results of modern archaeological excavations in Jerusalem enable us, I believe, to locate the site of King David’s palace,” she wrote in that article. “Even more exciting, it is in an area that is now available for excavation. If some regard as too speculative the hypothesis I shall put forth in this article, my reply is simply this: Let us put it to the test in the way archaeologists always try to test their theories—by excavation.”

Dr. Mazar stood by her theory for 10 years. Finally, she was permitted to begin excavating in 2005. Almost immediately, her team began uncovering a massive structure that dates to the time period that includes King David.

Back then, many scholars criticized her dating of the building. But that criticism proved unscientific. Even most of those same critics now accept the dating as accurate.

Today Dr. Mazar’s identification of the Large Stone Structure as the palace of King David remains controversial. Eilat did not rush to this conclusion; in fact, she always remained open to other explanations for what the Large Stone Structure might be. But looking at the size of the walls, the time period, the artifacts associated with it—and after considering all this evidence in the context of the ancient text—Dr. Mazar came to the most logical and scientific conclusion.

Dr. Mazar let the stones speak, and they strongly suggested this was the palace of King David.