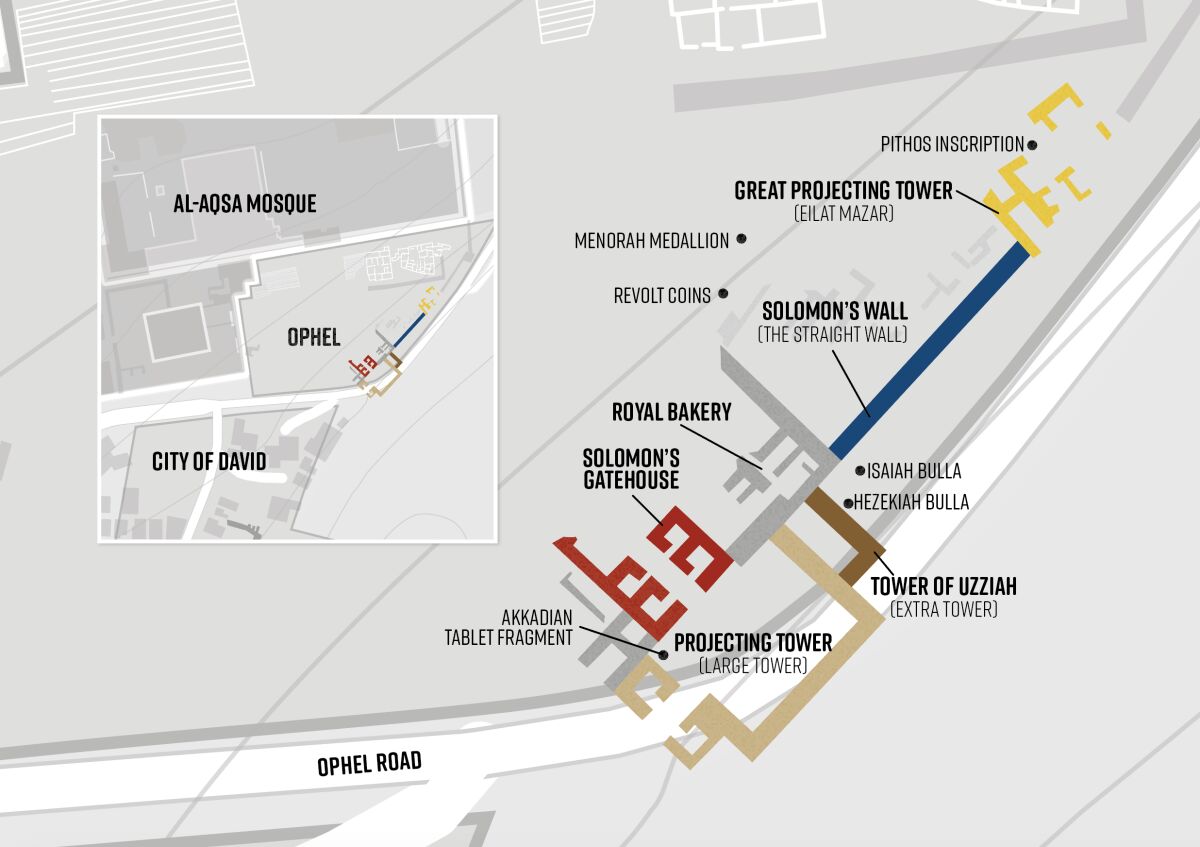

Discoveries of Eilat Mazar: The Ophel

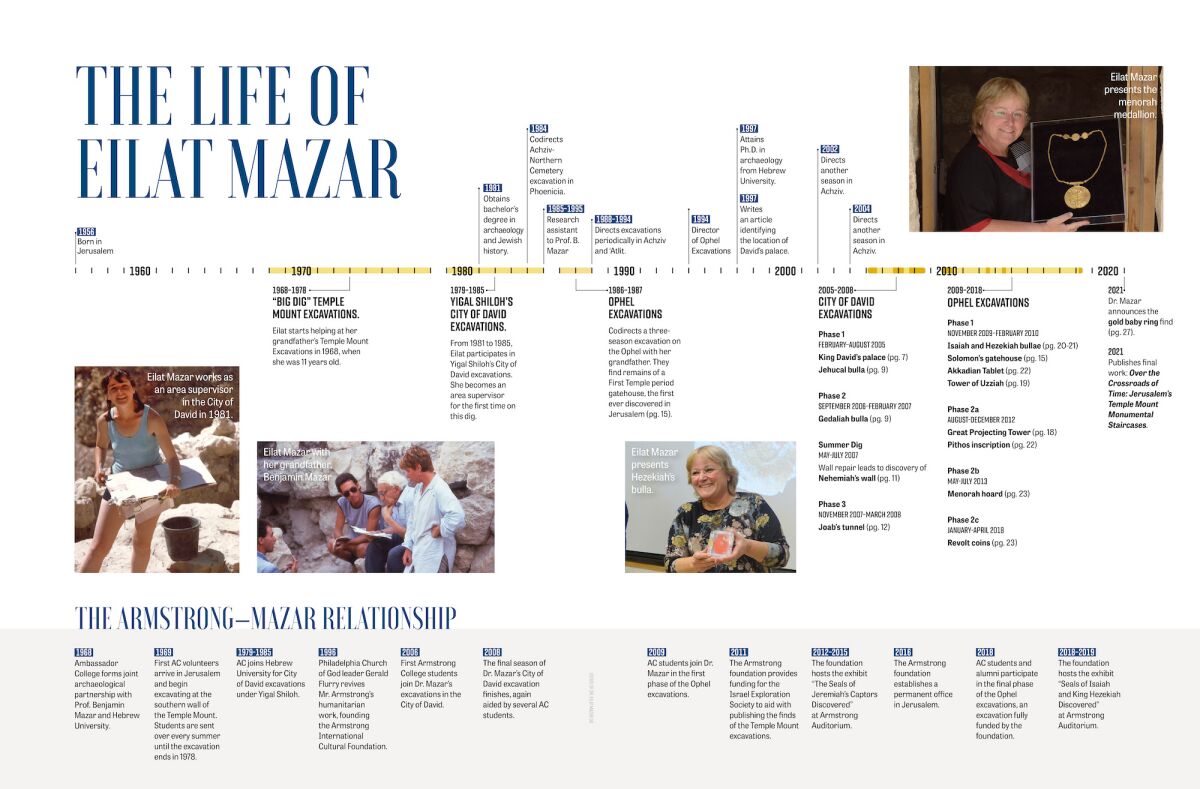

Though Dr. Mazar is best known for her work in the City of David, she spent most of her career excavating the Ophel. It was on the Ophel, south of the southern Temple Mount wall, where Eilat developed a passion for archaeology as a young child, helping on her grandfather’s “Big Dig” Temple Mount excavations that spanned from 1968 to 1978.

Following Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War, Prof. Benjamin Mazar and Hebrew University of Jerusalem were commissioned by Israel’s government to excavate the area. Working together with Herbert W. Armstrong and Ambassador College, the largest excavations ever conducted in Israel began. For a decade, these institutions worked side by side to uncover the southern border of the Temple Mount and the Ophel.

When Dr. Mazar began digging on the Ophel in the mid-1980s, much of the work had already been completed by her grandfather. With a lot of the top fill already excavated, Eilat would not have far to go to reach “gold”—Iron Age remains from the period of Judah’s monarchy!

Discovery One: Solomon’s Gatehouse

Dr. Mazar directed her first excavation on the Ophel in 1986–1987 with the guidance of her grandfather. Her objective was to find an original First Temple Period floor layer within a series of what were believed to be Iron Age rooms. Uncovered by Professor Mazar in earlier excavations, these rooms had been repurposed for use during the Second Temple Period. Dr. Mazar found her First Temple Period floor layer and a whole lot more.

The excavation started small, with a probe of 50-by-50 centimeters. Almost immediately, Dr. Mazar uncovered a burn layer that clearly related to the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem. The excavation expanded and within weeks the team had uncovered numerous pieces of 12 broken pithoi (large First Temple Period storage vessels). Dr. Mazar’s pithoi were the largest ever discovered in Jerusalem and evidence of an impressive administration.

The vessels dated to around the seventh century b.c.e. One of the pithoi bore a partial inscription that, upon reconstruction, read “Belonging to the Minister of the Bak[ery].” Another was inscribed with an image of a palm-type tree, perhaps signifying that the vessel held oil or date wine. Following these finds, Mazar began to refer to the site as the “Royal Bakery,” as part of the lavish Ophel “royal quarter.” (The Bible states that King Solomon built himself a new palace and royal area north of the City of David, on the Ophel: 1 Kings 7; Nehemiah 3:25-26.)

Adjacent to the Royal Bakery and connected to it by corridors, the Mazars found a limestone floor among a series of peculiar, small-chambered rooms. Initially, it wasn’t clear what the network of corridors and rooms was. But when the excavation surveyor drew up the architectural plans, Mazar and her grandfather immediately recognized what they had uncovered. Dr. Mazar described the moment in her final report on the excavation. “[W]e could not believe what we saw …. All of a sudden we realized that we were looking at a typical First Temple Period city gatehouse, characterized by four identical chambers and a large approach tower [Warren’s ‘Large Tower’]” (Discovering the Solomonic Wall in Jerusalem).

At the time, Dr. Mazar successfully dated the gatehouse and the “Large Tower” to the early Iron Age ii (the period of the early Judahite monarchy), but she wasn’t able to identify a more specific date. It wasn’t until nearly 25 years later, when she returned to excavate the Ophel in 2009, that Dr. Mazar was able to more accurately date them to the 10th century b.c.e., the time of King Solomon.

Dr. Mazar had uncovered archaeological evidence of King Solomon’s massive expansion of Jerusalem, as described in 1 Kings 6 and 7!

The exposed gatehouse has a preserved height of up to 6 meters and is built in a style similar to other ancient gatehouses discovered at Megiddo, Gezer and Hazor. These gates are known colloquially as “Solomonic gates” because they date to the same 10th-century period and indicate the presence of a strong, centralized government standardizing their construction. Fascinatingly, these same locations at this same time period are mentioned in a scripture about King Solomon: “And this is the account of the levy which king Solomon raised; to build … Jerusalem, and Hazor, and Megiddo, and Gezer” (1 Kings 9:15).

In her final report, Dr. Mazar compared the Ophel gatehouse with the one in Megiddo and showed how the wall lengths, the width of the central passages, the thicknesses of the walls, and the sizes of the chambers are virtually identical, almost to the centimeter. This “seem[s] to indicate that the two gatehouses were built according to an identical blueprint, most likely originating from the same architectural office,” Dr. Mazar concluded.

The Large Tower (discovered by Sir Warren, see “Discovery Three: Great Projecting Tower” below), provided a protective fortified right-angle entrance into the city gatehouse. Today this tower is nearly entirely covered by the Ophel Road (in fact, it is the primary thing holding the road up). But if it were excavated, the Large Tower would be one of the tallest ancient structures in all Israel (around 20 meters tall).

Dr. Mazar’s discovery is the only Iron Age gatehouse that has been found in the city of Jerusalem. Dr. Mazar referred to this structure as the “Water Gate,” as she believed it might have been the same gate mentioned in Nehemiah 3:25-27.

Discovery Two: Solomon’s Wall

During her 2009-2010 Ophel excavation, Dr. Mazar continued to excavate the giant wall extending from the gatehouse. This was no regular wall. It was 70 meters long, 3 meters wide, and in some sections measured 6 meters high. During the 2009-2010 dig (and then again during the 2012 dig), Dr. Mazar was able to accurately date the wall to the 10th century b.c.e.

Together, the dating of construction and its massive size indicated that it was built by a centralized and powerful government. “The city wall that has been uncovered testifies to a ruling presence. Its strength and form of construction indicate a high level of engineering,” Mazar wrote, attesting to the biblical account of Solomon’s powerful reign.

Based on the long, dead-straight nature of the wall (officially named the “Straight Wall”) and the way it was situated between two parallel “towers” at each end (the “Large Tower” and the “Great Projecting Tower”), Dr. Mazar also wondered if this was a section of the wall referred to as Miktsoa in Nehemiah 3:25.

She wrote: “Now that we knew that the Straight Wall was built together with the rest of the fortified complex, we could not help remembering Nehemiah 3:25, which seems to refer to this very wall. This verse describes two structures, one as an extension of the other: the Large Tower and the ‘Miktsoa,’ meaning the straight line formed between two sides. No structure fits this description better than the Straight Wall.”

Discovery Three: Great Projecting Tower

In 2012, Dr. Mazar and her team continued to excavate adjacent north. During this phase, Mazar uncovered the north end of the Straight Wall. Digging in the same area, she unearthed another large wall, one that connected to the Straight Wall and ran perpendicular. This wall ran to the east, underneath the Ophel Road, as with the Large Tower.

This structure was apparently another exceptionally large tower, although it was in a much worse state of preservation. Dr. Mazar concluded that this tower dated to at least the same period as the Straight Wall (given that the wall is built against it). Not much of this tower, sitting beneath the road (and also beneath a Byzantine tower), was able to be revealed. Dr. Mazar named it the “Great Projecting Tower” based on Nehemiah 3:27, which describes this as the next identifiable feature along the wall after the Water Gate, Projecting Tower and Miktsoa of verses 25-26.

Discovery Four: Tower of Uzziah

During the 2009–2010 excavation, Dr. Mazar excavated alongside another tower that was built directly against the Large Tower and the Straight Wall. This structure was called the Extra Tower. It was built with large ashlar stones—the largest found, in fact, before the building of the Temple Mount in the first century b.c.e. Given that this tower only abuts the Ophel wall, rather than being built into it, it was evidently built after the Large Tower and Solomonic wall. Without further excavation, Dr. Mazar was only able to get a general dating for the Extra Tower’s construction—she believed it was constructed between the 10th and eighth centuries b.c.e.

As always, Dr. Mazar searched her Bible to see if there were any biblical relevance to this First Temple period structure. As it turns out, there might be. 2 Chronicles 26 describes the rule of King Uzziah of Judah in the early eighth century b.c.e. Much like David and Solomon, Uzziah expended a lot of energy expanding and fortifying Judah, especially Jerusalem. Verse 9 says that “Uzziah built towers in Jerusalem at the corner gate, and at the valley gate, and at [against] the Turning [Miktsoa], and fortified them.”

Given that the dating meant the Extra Tower could have been built around the time of King Uzziah, and that it was situated against the same area as the Straight Wall (“Miktsoa”), Mazar concluded: “The question thus remains: Was the Extra Tower one of the towers built by Uzziah?”

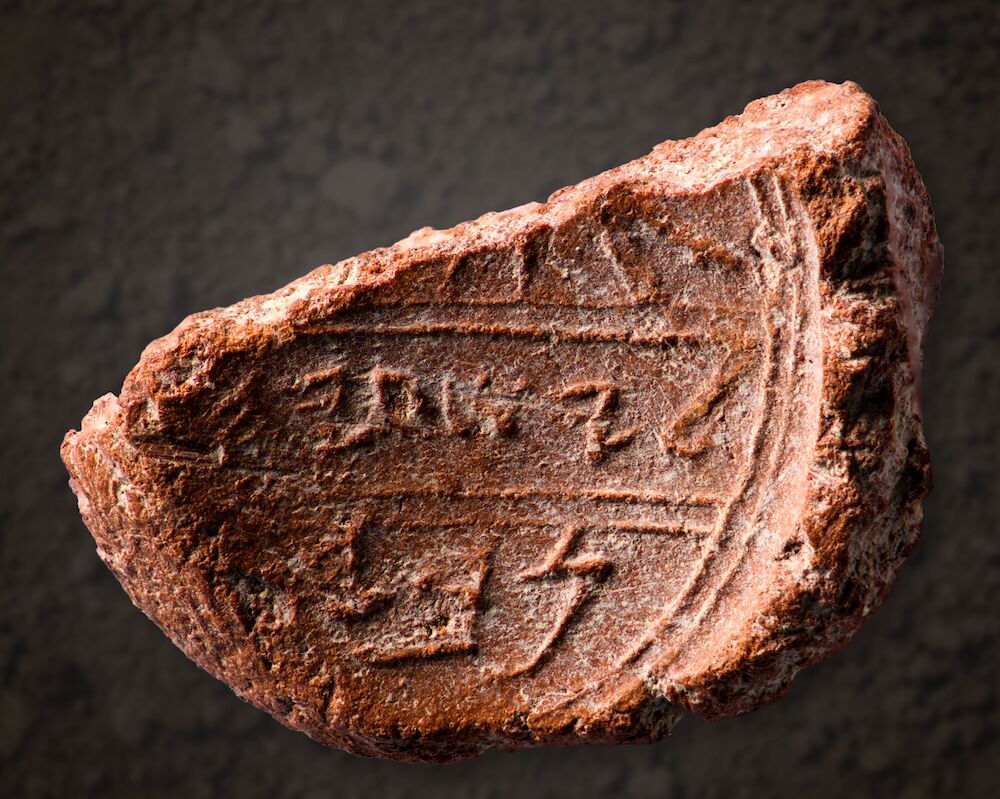

Discovery Five: Hezekiah Bulla

During the 2009–2010 phase of the Ophel excavations, Dr. Mazar made what she considered to be her single greatest discovery. While digging beside the Extra Tower, excavators removed material that was then wet-sifted to reveal multiple bullae, which were cataloged and set aside to be investigated later.

It wasn’t until 2015, when a member of her team began to seriously analyze one well-preserved bulla, that Dr. Mazar realized the significance of the find. The seal impression had an inscription that read: “Belonging to Hezekiah, son of Ahaz, King of Judah.”

This personal seal impression of Judah’s King Hezekiah remains the only confirmed bulla of an Israelite or Judahite king ever found on a controlled scientific excavation. (Others have been discovered but are unprovenanced from the antiquities market.)

Together with the names of two biblical kings, Hezekiah and Ahaz, the bulla displays an image of a sun with downturned wings, flanked by ankh symbols (which symbolize “life”). A similar winged-sun design can be found stamped on commonly found lmlk pottery handles of this period. The design is commonly associated with King Hezekiah.

Antiquities market seals and lmlk handles from apparently earlier on in Hezekiah’s reign have noticeably different symbolism. The designs on these artifacts include the winged scarab, representing the Egyptian god Khepri. The Prophet Isaiah warned Israel about the dangers of trusting in or forming an alliance with Egypt (Isaiah 30-31). 2 Kings 18:21 indicates that King Hezekiah placed his trust in Egypt for a time, and the scarab symbolism attests to that.

The imagery on the Hezekiah bulla that Dr. Mazar discovered, however, reflects a significant change. As summarized by Mazar, based on its design, this seal can best be attributed to the time directly after Assyria’s defeat, following King Hezekiah’s repentance and miraculous healing. The image of a sun with downturned—rather than proud, upturned—wings is unusual for a king and signifies humility.

The ankh symbols fit well with Hezekiah’s miraculous healing and the 15 years added to his life (Isaiah 38). Perhaps the winged sun, with the lines projecting from it, may even be a nod to the miracle of the “flying” sun that “turned back” on the sundial of Ahaz as God’s sign for Hezekiah’s healing (verse 8).

Several biblical verses parallel the sun and wings imagery. Psalm 84:12 reads, “For the Lord God is a sun and a shield”; Psalm 91:4 says, “[U]nder His wings shalt thou take refuge.” The language in Malachi 4:2 is remarkable—it’s almost as if Malachi was looking at Hezekiah’s royal seal as he was writing. “The Sun of Righteousness shall arise with healing in His wings …” (Malachi 4:2; nkjv).

Discovery Six: Isaiah Bulla

During the 2009–2010 dig, Dr. Mazar unearthed another bulla right alongside Hezekiah’s. In fact, this bulla was found just 3 meters away in the same strata of soil. It also dated to the end of the eighth century b.c.e.

The challenge with this bulla was that it was damaged, which made it difficult to interpret. Its top section was missing. But this missing section did not hinder its interpretation, as the top half contained a picture, or motif, not text. (A small remaining section of this motif can be seen on the upper right-hand side of the bulla.)

The lower half of the bulla contains the all-important inscription bearing the name of its owner. Two lines of text have been preserved. Both lines are slightly damaged on the left side by a visible thumbprint, probably made by the owner of the seal as he held down the edge of the clay while stamping it. Despite the damage, the first line of script is easy to interpret. All the experts agree that it reads, “Belonging to Isaiah.”

The debate revolves around the text on the bottom line, or lower register. Three letters are legible: “Nvy.” A Hebrew speaker, upon hearing this word (without adding vowels), would naturally take it to mean “prophet.” However, the Hebrew language is built on critical root letters. The final root letter of “prophet”—the aleph—is silent. Thus, “prophet” is correctly transliterated as Nvy’, with four letters, and properly pronounced with an added “a” vowel, Navy’.

But the place where the fourth letter, aleph, would be expected was damaged by the thumbprint. The thumbprint covers just after the third letter from the right on the bottom line (note that Hebrew reads from right to left). Much of the debate over this bulla revolves around whether or not the aleph existed. If there were an aleph, then the word would read “prophet.” If the aleph did not exist, then it would be a different word entirely.

Without knowing the identity of the missing letter, no one can say for certain what the inscription says. Some say Nvy is a reference to a specific place in Judah; others suggest it is referring to the known name “Novi” (not the name of Isaiah’s father).

While Dr. Mazar recognized the debate surrounding the identification of this Isaiah, she believed that among all the possible scenarios, the most logical conclusion was that the bulla inscription read, “Belonging to Isaiah the prophet.” A reconstruction of the outline of the bulla shows that the lower line indeed could (and should) have a fourth letter, to balance the seal design. Additionally, the seal was found right alongside the seal belonging to Hezekiah—the same king mentioned together with the Prophet Isaiah in over a dozen scriptures—in the same strata of soil, and in the same area of Jerusalem in which Isaiah the prophet served. Further, only select individuals owned their own private seals, so they were evidently important figures.

Given all of the above, Dr. Mazar asked the question: “What are the chances that this could be another Isaiah Nvy[?]—and not the famous Isaiah the Nvy’—the prophet? Thus, the most logical reconstruction of the bulla as ‘Belonging to Isaia[h the] Proph[et].’”

Mazar wrote: “[A]ccording to the Bible, the names of King Hezekiah and the Prophet Isaiah are mentioned in one breath 14 of the 29 times the name of Isaiah is recalled (2 Kings 19-20; Isaiah 37-39). No other figure was closer to King Hezekiah than the Prophet Isaiah.” Similarly to Jehucal and Gedaliah, King Hezekiah and Isaiah the prophet are paired together both in scriptures and in archaeology.

Discovery Seven: Akkadian Tablet Fragment

This tiny clay tablet fragment was one of the first of the small finds extracted from Dr. Mazar’s 2009–2010 Ophel season. Written in cuneiform text and dating to the 14th century b.c.e., it is the oldest text ever discovered in Jerusalem.

Due to its fragmentary condition, it is impossible to read the script with any context. The words “you,” “you were,” “them,” “to do” and “later” have been deciphered on the fragment. According to cuneiform expert Prof. Wayne Horowitz of Hebrew University, the high quality of the writing “indicates that the person responsible for creating the tablet (made from local clay) was a first-class scribe.”

The tablet fragment parallels the square-ish Canaanite Amarna letter tablets (also dated to during the 14th century b.c.e.); this one perhaps making up a small corner edge of just such a tablet. The Amarna Letters are a collection of Akkadian cuneiform-script clay tablets found in Amarna, Egypt, that contain correspondence from leaders throughout Canaan sent to Egypt’s pharaoh at the time. The letters urgently beseeched the pharaoh for help against the invading “Habiru” nomads who were taking over the land of Canaan. These “Habiru,” in name, actions and dating, are a good fit with the biblical account of the Hebrew invasion of the Promised Land at this same time in biblical chronology.

Several Amarna letters found in Egypt were sent specifically from the king of Jerusalem, such as the following: “May the [pharaoh] give thought to his land; the land of the king is lost. All of it has attacked me …. I am situated like a ship in the midst of the sea … the Habiru have taken the very cities of the king. Not a single mayor remains to the king, my lord; all are lost.” Mazar believed her fragment might have been an archival copy of one such letter.

It is also notable that her Jerusalem tablet was burned; Judges 1:8 says the tribe of Judah “set the city [Jerusalem] on fire” before leaving it in the hands of the enemy.

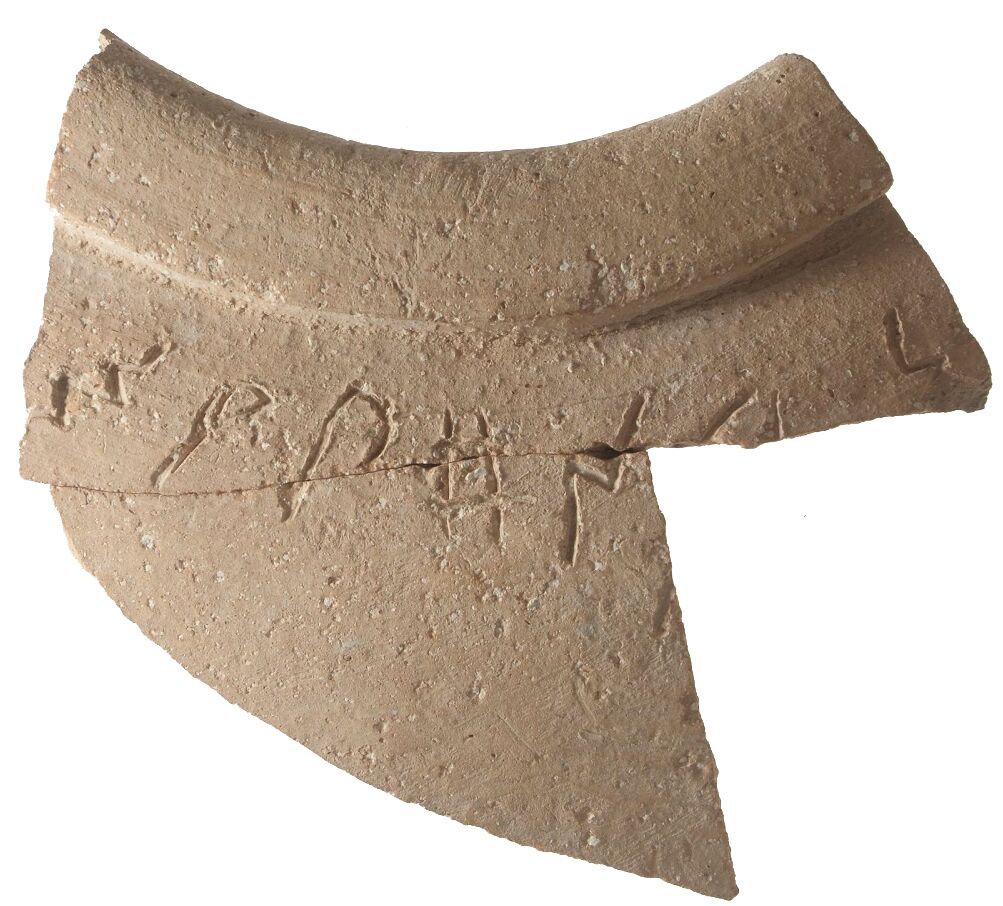

Discovery Eight: Pithos Inscription

During Dr. Mazar’s 2012 excavation season, another remarkable inscription surfaced—this time on the rim of a large ancient pithos storage vessel. Dating to the 11th or 10th century b.c.e., during or just before the period of King David, this inscription is the oldest alphabetical script ever discovered in Jerusalem.

There has since been significant debate about whether or not the inscription is Canaanite or Hebrew. The alphabets are related, and it can be extremely hard to tell them apart at this early period. Dr. Gershon Galil of Haifa University believes one of the words on the inscription refers to wine—suggesting that the pithos was designated either to contain the beverage or at least the ingredients for producing it. The inscription has primarily been recognized as Canaanite, and given the dating, this would fit the biblical account of this area being operated, before David purchased it, by the famous Canaanite Jebusite of the Bible, Ornan (2 Samuel 24; 1 Chronicles 21), who operated this upper Ophel/Temple Mount area as an agricultural site.

Discovery Nine: Menorah Hoard

While most of Dr. Mazar’s most famous finds are related to the Bible, there are exceptions. One of her most famous finds comes from a much later period and is notable for its inherently Jewish appearance. This kind of find is the “holy grail” of archaeology—gold treasure—and Dr. Mazar heralded this as a “once in a lifetime” discovery.

Only five days into Dr. Mazar’s 2013 Ophel season, her team found a hoard of 36 gold coins, silver and gold jewelry, and other silver and gold items inside a sixth-century c.e. Byzantine structure. This building is located about 50 yards south of the Temple Mount. The most notable treasure was a large gold medallion and chain, the face of the medallion stamped with a large seven-branched menorah symbol, a Torah scroll and a shofar.

Dr. Mazar believed the menorah medallion was probably the sort typically used to adorn a large synagogue Torah scroll. If so, the medallion and accompanying items would be the earliest known Torah scroll ornaments ever discovered.

Based on the date and the nature of the strata, as well as the minting of the gold coins, the hoard had evidently been hurriedly buried in the floor of the Byzantine building at the beginning of the seventh century c.e. Based on historical sources, Dr. Mazar was able to get even more specific—postulating that the treasure was abandoned around the time of the Persian conquest of Jerusalem in c.e. 614.

The Jews at the time had been promised by the Persians that if they helped overthrow the Christian Byzantines, they would be allowed to rebuild the temple. This they did, and there is speculation that construction even got as far as an altar—but suddenly, the Persians turned on the Jews and violently drove them out of the city. Dr. Mazar believed the menorah medallion hoard was a gift intended for the reconstruction of the edifice (with the gold coins to be melted down for other items)—but that the treasure was hurriedly buried as the Jews fled for their lives.

The menorah medallion and accompanying treasure are now featured in the Israel Museum as one of the three largest—and certainly the most symbolically significant—gold hoards ever discovered in Israel.

Discovery Ten: Revolt Coins

Dr. Mazar’s fourth and final excavation on the Ophel (in 2018) concentrated on a large Ophel cave, as well as an upper Byzantine building. This dig was fully funded, and largely staffed by, Herbert W. Armstrong College. One of the significant discoveries of this season was the large number of 2,000-year-old Revolt coins found in the Ophel cave.

The 15-by-8-meter cave was discovered in near- pristine condition, virtually untouched since the Jewish Revolt of 66–70 c.e. The Jewish historian Josephus wrote that the Jews descended into tunnels and caves in order to hide during the closing moments of the siege against Jerusalem by the Romans. This was the case on the Ophel, and a significant hoard of coins was found throughout the cave.

During the four-year Great Revolt, the Jews minted their own coins. The coins were decorated with various Jewish symbols, including the traditional “four plant species” of the Feast of Tabernacles/Sukkot—palm, myrtle, citron and willow—and a goblet that was likely part of the temple service. The most common of these coins are the Year Two coins.

The rarest are the Year Four coins, showing that—besides Jerusalem—most of Judea had been reconquered by Rome to that point. It was during this final year that the ancient-Hebrew-script message on the coins changed. Instead of proudly declaring, “To the Freedom of Zion,” they bore the sober message, “To the Redemption of Zion.”

It was most notably these Year Four coins that were discovered in the cave, attesting to its use right at the closing moments of Jerusalem’s fall. The dozens of coins that were found constitute one of the largest (if not the largest) Year Four coin hoards ever discovered.

The coins were found alongside broken pottery vessels, including jars and cooking pots. The undisturbed cave, said Mazar, created a “time capsule” of Jewish life during the revolt. “It’s not a usual phenomena that we can come to such a closed cave,” she said, “untouched [for] 2,000 years, including the very last remains of life of the people who were besieged in Jerusalem, suffered in Jerusalem, till the very last minute of the Second Temple Period.”